Dalrev Vol61 Iss4 Pp718 734.Pdf (4.730Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Railway Items from Area Papers - 1901

Local Railway Items from Area Papers - 1901 04/01/1901 Ottawa Citizen Ottawa Electric There was a partial tie up of the Rideau Street line of the street railway last night caused by a car jumping the track. As car No. 64 was speeding northwards down the Nicholas Street hill, the motorman seemed to lose control and on reaching the curve was going too fast to turn. The car went straight ahead, jumping the track, stopping within two feet of the sidewalk in front of Bourque's store. The auxiliary car and gang were summoned and had a big contract getting the car back on the track. 04/01/1901 Eastern Ontario Review Canada Atlantic Alexandria New Stage Line Mr. John Morrow, C.A.R. agent has succeeded in establishing a regular stage line from Alexandria to Green Valley to connect with all C.P.R. trains. 08/01/1901 Ottawa Citizen Chaudiere McKay Milling One of the capital's oldest manufacturing concerns, the McKay Milling Company, is about to go out of business. After the April fire which gutted the buildings and destroyed the plant and stock therein the company sold the mill site and water power at the Chaudiere to Mr. J.R. Booth. A good figure was obtained and the directors thought it was advisable to wind up the affairs of the company rather than seek another site and start anew at present. The McKay Milling Company was founded over 60 years ago in the days of Bytown by the late Hon. Thomas McKay.-- It is understood Mr. -

2016 Volume 17 No. 3 Fall

Historic Gloucester Newsletter of the GLOUCESTER HISTORICAL SOCIETY www.gloucesterhistory.com Vol. 17, No. 3 Fall 2016 RAF 18 Squadron Blenheim Crew, Summer 1941. Lawrence Larson, Scotland; Geoffrey Robinson, England; and James Woodburn, Canada Historical Gloucester - 2 - Vol 17, N0 3, 2016 Contents From the President’s Desk……………………………………........................ Glenn Clark 3 A Tribute to Our RAF Blenheim Crew……………...………….. David Mowat and John Ogilvie 4 Rideau Hall - A Brief History………………………………………………… 7 Membership Form……………………………………………….................... 10 THE GLOUCESTER HISTORICAL SOCIETY WOULD LIKE TO ANNOUNCE THAT ITS HISTORY ROOM WILL BE OPEN TO THE PUBLIC DURING THE WINTER MONTHS BY APPOINTMENT ONLY. LOCATION: 4550B BANK STREET (ENTRANCE ON LEITRIM ROAD) FOR MORE INFORMATON OR TO MAKE AN APPOINTMENT Contact Mary Boyd at 613-521-2082 or [email protected] Cover Photo: The cover photo shows the three-man Blenheim Bomber crew in 1941. Shown are Lawrence Larson from Scotland; Geoffrey Robinson from England and James Woodburn, a native of the Township of Gloucester, Canada. Photo: David Mowat Historic Gloucester is published by The Gloucester Historical Society. It is intended as a Newsletter to members of the Society to provide interesting articles on Gloucester’s past and to keep them informed of new acquisitions by the Museum, publications available, upcoming events and other items of general interest. Comments and suggestions regarding the Newsletter are always welcome. Gloucester Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the City of Ottawa. Historic Gloucester - 3 - Vol 17, No 2, 2016 President’s Report By Glenn Clark We are approaching a very important year in the history of our country, our sesquicentennial. -

![A History of Old Bytown and Vicinity, Now the City of Ottawa [Microform]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7734/a-history-of-old-bytown-and-vicinity-now-the-city-of-ottawa-microform-1297734.webp)

A History of Old Bytown and Vicinity, Now the City of Ottawa [Microform]

«nd ^^h v> 0^\t^^< ^^J<' id. IMAGE EVALUATION TEST TARGET (MT-3) i^llllM !IIII25 1.0 mm3.^ 6 Mi. 2.0 I.I 1.8 1.25 U ill! 1.6 4' V PhotogiBphic 23 WEST MAIN STREET WfBSTER, NY. 14580 Sciences (7U) 872-4503 Corporation CIHM/ICMH CIHM/ICMH Microfiche Collection de Series. microfiches. Canadian Institute for Historical Microreproductions / Institut Canadian de microreproductions historiques Technical and Bibliographic Notes/Notes techniques et bibliographiques L'Institut a microfilm^ le meilleur exemplaire The Institute has attempted to obtain the best qu'il lui a 6t6 possible de se procurer. Les details original copy available for filming. Features of this du copy which may be bibliographically unique, de cet exempiaire qui sont peut-dtre uniques bibliographique, qui peuvent modifier which may alter any of the images in the point de vue reproduite, ou qui peuvent exiger une reproduction, c which may significantly change line image modification dans la m6thode normale de filmage the usual method of filming, are checked below. sont indiquds ci-dessous. Coloured covers/ Coloured pages/ ^ Couverture de couleur Pages de couleur Covers damaged/ Pages damaged/ D Couverture endommagee Pages endommag6es Covers restored and/or laminated/ Pages restored and/or laminated/ M Couverture restaur6e et/ou ,jellicul6e 3 Pages restaur6es et/o-j pellicul^es discoloured, stained or foxed/ Cover title missing/ Pages Pages ddcolor^es, taci^et^es ou piquees D Le titre de couverture manque Coloured maps/ Pages detached/ Caries g6ograDhiques en couleur Pages d^tachees Coloured ink (i.e. other than blue or black)/ 0Showthrough/ Encre de co'jieur (i.e. -

Behind the Roddick Gates

BEHIND THE RODDICK GATES REDPATH MUSEUM RESEARCH JOURNAL VOLUME III BEHIND THE RODDICK GATES VOLUME III 2013-2014 RMC 2013 Executive President: Jacqueline Riddle Vice President: Pamela Juarez VP Finance: Sarah Popov VP Communications: Linnea Osterberg VP Internal: Catherine Davis Journal Editor: Kaela Bleho Editor in Chief: Kaela Bleho Cover Art: Marc Holmes Contributors: Alexander Grant, Michael Zhang, Rachael Ripley, Kathryn Yuen, Emily Baker, Alexandria Petit-Thorne, Katrina Hannah, Meghan McNeil, Kathryn Kotar, Meghan Walley, Oliver Maurovich Photo Credits: Jewel Seo, Kaela Bleho Design & Layout: Kaela Bleho © Students’ Society of McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada 2013-2014 http://redpathmuseumclub.wordpress.com ISBN: 978-0-7717-0716-2 i Table of Contents 3 Letter from the Editor 4 Meet the Authors 7 ‘Welcome to the Cabinet of Curiosities’ - Alexander Grant 18 ‘Eozoön canadense and Practical Science in the 19th Century’- Rachael Ripley 25 ‘The Life of John Redpath: A Neglected Legacy and its Rediscovery through Print Materials’- Michael Zhang 36 ‘The School Band: Insight into Canadian Residential Schools at the McCord Museum’- Emily Baker 42 ‘The Museum of Memories: Historic Museum Architecture and the Phenomenology of Personal Memory in a Contemporary Society’- Kathryn Yuen 54 ‘If These Walls Could Talk: The Assorted History of 4465 and 4467 Blvd. St Laurent’- Kathryn Kotar & Meghan Walley 61 ‘History of the Christ Church Cathedral in Montreal’- Alexandria Petit-Thorne & Katrina Hannah 67 ‘The Hurtubise House’- Meghan McNeil & Oliver Maurovich ii Jewel Seo Letter from the Editor Since its conception in 2011, the Redpath Museum’s annual Research Journal ‘Behind the Roddick Gates’ has been a means for students from McGill to showcase their academic research, artistic endeavors, and personal pursuits. -

A Visit to the Redpath Sugar Museum

Number 61/Spring 2017 ELANELAN Ex Libris Association Newsletter www.exlibris.ca INSIDE THIS ISSUE Refined History: A Visit to the Redpath 1 Sugar Museum Refined History: A Visit to the By Tom Eadie President’s Report 2 Redpath Sugar Museum By Elizabeth Ridler By Tom Eadie Ex Libris Biography Project 2 n October 16, 2016, a group By Nancy Williamson of Ex Libris members ELA 2016 Annual Conference Report 3 toured the Redpath Sugar By Barbara Kaye OMuseum located in the Redpath Taking it to the Streets: 4 Sugar Toronto Refinery at 95 Queen’s Summit on the Value of Libraries, Archives Quay East. Richard Feltoe, Curator and Museums [LAMs] in a Changing World and Redpath Corporate Archivist, By Wendy Newman led the tour, which featured his Technology Unmasked: Hoopla 5 knowledgeable explanations, displays By Stan Orlov of artifacts, and an interesting Richard Feltoe, Curator and Redpath Corporate Archivist, above. Enjoying Church Archives, 5 video about sugar production. lunch at Against the Grain, below. one thing leads to another… Redpath Sugar began as the Canada By Doug Robinson Sugar Refining Company, established Celebrating Canada’s Stunning 6 in Montreal in 1854 by John Redpath Urban Library Branches (1796–1869). Born in Scotland and By Barbara Clubb orphaned when young, Redpath Stratford Festival Archives 6 rose from obscurity to eminence. An By Judy Ginsler apprentice stonemason, he immigrated to Canada at the age of 20. Over time A Memory of Marie F. Zielinska (1921–2016) 7 Prepared by Ralph W. Manning, Redpath became a building contractor with contributions from Irena Bell, involved in the construction of many Frank Kirkwood, Marianne Scott, well-known Montreal buildings, and Jean (Guy) Weerasinghe including Notre-Dame Basilica, the development of sugar production and Library Treasures of Britain: 8 Montreal General Hospital, and the refining in the context of social issues The Royal College of Surgeons Bank of Montreal headquarters. -

Heritage Preservation and the Lachine Canal Revitalization Project by Mark London

Heritage Preservation and the Lachine Canal Revitalization Project by Mark London Summary Between 1997 and 2002, the City of Montreal and the Government of Canada invested $ I 00 million to reopen the Lachine Canal to recreational boating and to catalyze the revitalization of the adjacent working-class neighbourhoods, in decline since the canal closed in I 970. The canal's historic infrastructure was largely restored. The design of newly landscaped public spaces focused on helping visitors understand the past of this cradle of Canadian industrialization. However, the rapid response of the private sector's $350 million worth of projects already leads to concern about the impact of real estate development on the privately owned industrial heritage of the area. Sommaire Entre 1997 et 2002, la Ville de Montreal et le gouvernement du Canada ont investi I 00 millions de dollars af,n de rouvrir le canal de Lachine a la navigation de plaisance et de catalyser la revitalisation des quartiers populaires adjacents, en dee/in depuis la fermeture du canal en 1970. L'infrastructure historique du canal a ete en grande partie restauree. L'amenagement des nouveaux espaces publics visait a aider /es visiteurs a comprendre l'histoire de ce berceau de /'industrialisation manufacturiere canadienne. Neanmoins, la rapidite de la reponse du secteur prive - deja des projets d'une valeur de 350 millions de dollars - sou/eve des craintes quant a /'impact du developpement immobilier sur le patrimoine industriel prive de la region. he Lachine Canal Revitalization TProject is one of the largest heritage restoration/waterfront revitalization projects in Canada in recent years. -

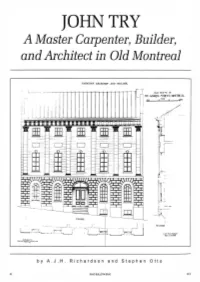

JOHN TRY a Master Carpenter, Builder, and Architect in Old Montreal

JOHN TRY A Master Carpenter, Builder, and Architect in Old Montreal CANADIAN ARCHITEC" AND BUILUER. OUl ltU\ '~1 ·: IS ST. G.\I JI-<!f:l. Sll{l'.t-:T. MON1l{I ':.\L ......____..__''"-"'......__?r-e. _/ ~..,.- ... : ... · ~- . , I I C fril .""'-"" t liunt.'~ M.. \.\oC\., U . ~ by A. J.H. Richardson and Stephen Otto 32 SSAC BULLETIN SEAC 22:2 Figure 1 (previous page). House on St Gabriel Street, Montreal, measured and drawn by Cecil Scott Burgess in 1904 and reproduced in the supplement to Csnsdisn Archit1ct snd Buildsr 18, no. 211 (July 1905). This is the house built for David Ross in 1813-.15. (Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library) Figure 2 (left). Watercolour of the interior of Christ Church Cathedral, Montreal, 1852; James Duncan (1806·1881), artist. (McCord Museum of Canadian History, M6015) ohn Try was likely born in 1779 or 1780; when he died suddenly on 14 August 1855, on holiday at Saco near Portland, Maine, he was said to be seventy-five years Jold and a native of England.1 His exact birthplace has not been identified. Nor is it known where he was trained in his trade as a carpenter, although his rapid success in Canada suggests he arrived here well qualified. Try appears to have emigrated to Montreal in 1807. Confirmation for this year is found in a statement he made in 1841: "I have resided in this City thirty-four years."2 More circumstantial evidence exists in an application that David Ross, a lawyer, made in 1814 to the Governor-in-Chief to allow either "Daniel Reynard Architect and Stucco worker," or "--Roots Plasterer and Stucco worker," both of Boston, to enter the province to work on a large house Ross was building in Montreal (figure 1) .3 Vice-regal consent was needed because a state of war still existed between Britain and the United States. -

Download Book

Chapter 1 MacKay's Wharf On the morning of Thursday, 11 February, 1864, there appeared in the Daily Spectator, the following item of news: "MacKay's Wharf -Among the many improvements recently effected in this city, there is none likely to confer greater benefits, in proportion to its extent, than the new wharf built by Mr. Aeneas D. MacKay, at the foot of James St. The construction of railways proved highly injurious to the forwarding interests and almost ruined the business; but we are glad to see that the energy of one at least has not been entirely crushed out. His enterprise in erecting a new wharf and warehouses, by far the most extensive and costly in the Province is most commendable, and shows that there are true patriots amongst us still. Mr. MacKay has invested a large amount of money in his new wharf and warehouses; he has no such fears as some of our people have manifested and seems determined to risk his all in an enterprise which we hope will turn out a profitable one. Mr. MacKay settled here in 1852, while sailing as purser on the steamer CHAMPION, Capt. A. Marshall. In 1854 he took a job as clerk with Messrs. Holcomb & Henderson, forwarders, and four years later he took over their business in Hamilton. -2- At first he was unsuccessful, but by energy and unwearying industry, he finally succeeded and now owns the finest wharf property in Upper Canada. The wharf is built on the site of the old one, is very commodious and is calculated to accommodate all the shipping at this port. -

Land Capitalization, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861 Roderick Macleod

Document generated on 09/25/2021 8:45 a.m. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada The Road to Terrace Bank: Land Capitalization, Public Space, and the Redpath Family Home, 1837-1861 Roderick Macleod Volume 14, Number 1, 2003 Article abstract The efforts of nineteenth-century Montreal land developer John Redpath to URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/010324ar subdivide his country estate into residential lots for the city's rising middle DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/010324ar class were marked by a shrewd sense of marketing and a keen understanding of the political climate – but they were also strongly determined by the Redpath See table of contents family's need for status and comfort. Both qualities were provided by Terrace Bank, the house at the centre of the estate, and both would only increase with the creation of a middle-class suburb around it on the slopes of Mount Royal. Publisher(s) As a result, the Redpath family home, and the additional homes built nearby for members of the extended Redpath family, influenced all stages of the The Canadian Historical Association / La Société historique du Canada planning and subdivision process, which met with great success over the course of the 1840s. In its use of personal correspondence, notarial documents, ISSN plans, the census, and cemetery records, this paper brings together elements of city planning, political and social history, and family history in order to 0847-4478 (print) provide a nuanced picture of how the nineteenth-century built environment 1712-6274 (digital) was shaped and how we should read pubic space. -

Mayor Proclaims Thomas Mckay Day > See Article on Page 7 October 2012

Mayor Proclaims Thomas McKay Day > See Article on page 7 October 2012 After the Fire www.newedinburgh.ca Passion at its fiery best at Lumière 2012. Photo: Andrew Alexander On Beechwood, No News is Bad News New Bridge Won’t Solve By Jane Heintzman solid hoarding placed along After the structure was erect- What began as a tragedy in Beechwood in the course of the ed, it wasn’t long before the frus- Ottawa’s Traffic Woes March 2011 became, as the summer, which serves at least tration of some local residents months rolled by without vis- to mask the scarred landscape boiled over, and a large banner A coalition of communities (including Manor Park ible signs of progress, a grow- that weighed so heavily on our was emblazoned on the hoard- Community Association, Rockcliffe Park Residents ing inconvenience, and finally spirits for over a year, as well ing with the message: OUR Association and New Edinburgh Community Alliance), an outrage as both residents and as to provide a more effective COMMUNITY NEEDS YOU demanding a smarter solution to the National Capital businesses in New Edinburgh barrier to entry on to the site, TO BUILD SOMETHING- and the surrounding communi- which had become a hazardous NOW!! Needless to say, the Region’s traffic problems engaged Freilich and Popowitz ties approach the end of their magnet for adventurous young property owner had the banner to objectively review and critique the Interprovincial collective rope in the face of folks and even thieves attracted removed in short order, and Crossings Study. the changeless, derelict site of by loose bits of copper pipe and the once commercial heart of other marketable materials. -

Summer – June 2013

The Presbyterian Church in Canada 82 Kent St., Ottawa, ON K1P 5N9 Office: 232-9042 Fax: 232-1379 www.StAndrewsOttawa.ca facebook.com/StAndrewsOttawa Summer – June 2013 GHOTI and the Christian Journey - Andrew Johnston In this issue: As a member of a household that includes a nearly-graduated From the Minister ...................................................... - 1 - speech pathologist, I was News from the Kirk Session ....................................... - 2 - offered the following Election of Elders ....................................................... - 3 - fascinating suggestion … PROVISIONARIES ........................................................ - 6 - If the ‘gh’ sound in ‘enough’ is A Bird’s-Eye View of the Presbytery of Ottawa ......... - 7 - pronounced ‘f’, and the ‘o’ in ‘women’ makes What is Invitations? ................................................... - 8 - the short ‘i’ sound, and the ‘ti’ in ‘nation’ is About St. Andrew’s in Action ..................................... - 8 - pronounced ‘sh’, then the word ‘ghoti’ is pronounced just like ‘fish’. Let’s celebrate our Choir! .......................................... - 9 - Update from the Children’s Choir ............................ - 10 - Welcome to the English language! Passages ................................................................... - 10 - The fish has been for long a symbol for the Anniversary Celebrations ......................................... - 11 - Christian faith, and it made me think that the Christian journey is as surprising as any Wednesday -

Redimensioning Montreal: Circulation and Urban Form, 1846-1918

Redimensioning Montreal: Circulation and Urban Form, 1846-1918 Jason Gilliland Dept ofGeography McGill University Montreal August 2001 A thesis submitted to the Faculty ofGraduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment ofthe requirements ofthe degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy © Jason Gilliland, 2001 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1 A ON4 canada Canada Your fiIB vor,. rétë_ Our 61e Notre référence The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National LibraI)' ofCanada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies ofthis thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership ofthe L'auteur conselVe la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permtSSIon. autorisation. 0-612-78690-0 Canada Abstract The purpose ofthis thesis is to explore certain ofthe dynamics associated with the physical transformation ofcities, using Montreal between 1846 and 1918 as a case study. Beyond the typical description or classification ofurban forms, this study deals with the essential problem ofhow changes in form occurred as the city underwent a rapid growth and industrialization.