Mapping Men: Towards a Theory of Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Daily Egyptian, June 16, 1988

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC June 1988 Daily Egyptian 1988 6-16-1988 The aiD ly Egyptian, June 16, 1988 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_June1988 Volume 74, Issue 156 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, June 16, 1988." (Jun 1988). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1988 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in June 1988 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Daily Egyptian Southern Illinois University at Carbondale Thursday, June 16,1988, Vol. 74, No. 156, Page 12 Reagan again urges aid for Contras WASHINGTON (uPI) - Nicaragua do have a force here and what we're going to rebels - a cornerstone of the Sandinistas are not going to President Reagan, putting there that can be used to bring do," Reagan said. president's foreign policy. democratize ... and it seems to part of the blame on Congress about an equitable set But asked if he thinks it is White House spoiresman me that the efforts that have for the collapsed peace talks in tlement." time for m9re military aid for Marlin Fitzwater said no been made in CongrelS and Nicaragua, said Wednesday But Reagan refused to say if the rebels, Reagan said, "I decision was made on a new succeeded i.'1 reducing and the need for Military aid for or when he would actually think it is so apparent that that funding request though con eliminating our ability to help the Contra rebels is now "so submit an aid package - is what is necessary it woold suHations were continuing. -

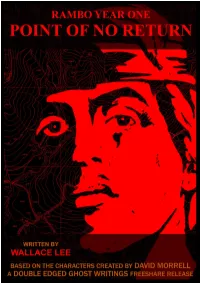

Point of No Return

1 Wallace Lee's POINT OF NO RETURN Based on characters created by: David Morrell Test reading: Piero Costanzi Orazio Fusco Flavio Brio Gary Rhoac Mat Thomas Marchand Italian language editing by: Flavio Brio Website Design by: Marco Faccio Cover by: Marco Faccio from a drawing by Ambra Rebecchi and a concept by Wallace Lee a very special thanks To all of the veterans that helped me with this, ..words are not enough. Thank you from the bottom of my heart. Double Edged Ghost Writings, 2017 [email protected] Copyright: Copyright disclaimer: The characters of Rambo and Col. Sam Trautman were created by David Morrell in his novel First Blood, copyright 1972, 2017. All rights reserved. They are included here with the permission of David Morrell, provided that none of the story is offered for sale. The use of the characters here does not imply David Morrell's endorsement of the story. The First Blood knife was designed by Arkansas knife-smith Jimmy Lile (1982). Everything you read here that is not mentioned in any official licensed Rambo movie or novel at the time of this publishing (2017), is an original work by the author. Electronic copy for private reading, free sharing and press evaluation only. No commercial use allowed. 2 POINT OF NO RETURN 3 IMAGES 4 Here, we can see a reconnaissance team made up of both indigenous and American personnel sporting long-range equipment only moments after returning home from their last mission. 5 This picture shows an example of emergency stepladder use. Oftentimes, rescuing an SOG team was an extremely precarious feat and needed a quick rescue like the one only a stepladder could offer. -

Politics of Sly� Neo-Conservative Ideology in the Cinematic Rambo Trilogy: 1982-1988

Politics of Sly Neo-conservative ideology in the cinematic Rambo trilogy: 1982-1988 Guido Buys 3464474 MA Thesis, American Studies Program, Utrecht University 20-06-2014 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Theoretical Framework ........................................................................... 12 Popular Culture ............................................................................................................................................ 13 Political Culture ........................................................................................................................................... 16 The Origins Of Neo-Conservatism ....................................................................................................... 17 Does Neo-Conservatism Have A Nucleus? ....................................................................................... 20 The Neo-Conservative Ideology ........................................................................................................... 22 Chapter 2: First Blood .................................................................................................... 25 The Liberal Hero ......................................................................................................................................... 26 The Conservative Hero ............................................................................................................................ -

First Blood Vendetta

FIRST BLOOD: VENDETTA Written by Gary Patrick Lukas Based on the characters by David Morrell. In his fifth action packed installment, Rambo finally goes home, only to find his father isn't the only one glad to see him back, but for different reasons of course. [email protected] WGA Registration: I245270 Copyright(c)2012 This screenplay may not be used or reproduced without the express written permission of the author. FADE IN: To a piano accompaniment of “IT’S A LONG ROAD”. EXT. ROUTE 66 - DAY In b.g. a distant figure simmering and wavering in the heat haze of the day. In the f.g. is a ROAD SIGN ‘Route 66’ CREDIT SEQUENCE - EARLY MORNING A LONELY FIGURE walks the old highway alone, with the occasional car WHIZZING past him. He is wearing an old 70s style army jacket and a large backpack is slung over his shoulder. His hair is long and unkempt. His name is JOHN RAMBO! Rambo hears a CAR pull up behind him and turns. CU. ON CAR DOOR to see that it’s a police car for Navajo county. It is slowly accompanying Rambo as he is walking by the side of the road. Rambo is getting nervous. PAUSE CREDITS The window goes down and a head pokes out. The head belongs to a deputy called WEAVER. WEAVER Hey Buddy. Wanna ride? RAMBO (hesitant) Eh... It’s OK officer. Just passing through. WEAVER Holbrook is still about 10 miles up ahead. Let me do my good deed for the day and take you to town. -

Wounded Warriors: Contemporary Representations of Soldiers' Suffering by Alison M Bond a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

Wounded Warriors: Contemporary Representations of Soldiers’ Suffering By Alison M Bond A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Wendy L Brown, Chair Professor Ron E Hassner Professor Kinch Hoekstra Professor Ramona Nadaff Fall 2017 Wounded Warriors: Contemporary Representations of Soldiers’ Suffering Copyright 2017 by Alison M Bond Abstract Wounded Warriors: Contemporary Representations of Soldiers’ Suffering by Alison M Bond Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Wendy L Brown, Chair There has been a long-term suspicion in religious and psychological literatures that unethical wars will have an especially detrimental impact on the soldiers who fight in them. This project examines public depictions of the psychological suffering of contemporary U.S. soldiers, evaluating their effects on public discourses about war’s ethics. The analysis shows that over the past decade, these portrayals have developed potentially detrimental effects on civic processes, limiting and constraining public debate about war’s justifiability. Furthermore, the full expression of soldiers’ varied experiences of distress also appears to be constricted, preventing insights that might emerge into the ethics of current wars. In trying to understand how different discourses of suffering tend either to illuminate or to foreclose debates about a war’s justifiability, I draw on a variety of sources including medical discourse, political debate, advocacy materials designed to inform the public about soldiers’ post-combat struggles, and cultural accounts of soldiers’ distress in journalism, film and literature. -

Duty and Humanism in Sylvestre Stallone's Film “Rambo 4”

Duty and Humanism in Sylvestre Stallone’s Film “Rambo 4” Final Project Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English by Zico Muhardhiansyah 2250406545 ENGLISH DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND ARTS SEMARANG STATE UNIVERSITY 2011 i “Life for nothing or die for something” (American Proverb) To: My Parents ii iii SURAT PERNYATAAN Dengan ini saya: Nama : Zico Muhardhiansyah NIM : 2250406545 Prodi/ jur : Sastra Inggris/ Bahasa dan Sastra Inggris Menyatakan dengan sesungguhnya bahwa skripsi/ tugas akhir/ final project yang berjudul: Duty and Humanism in Sylvestre Stallone’s Film “Rambo 4” yang saya tulis dalam rangka untuk memenuhi salah satu syarat untuk memperoleh gelar sarjana sastra ini benar-benar karya saya sendiri, yang saya hasilkan setelah melalui bimbingan, diskusi, dan pemaparan atau semua ujian. Semua kutipan, baik yang langsung maupun tidak langsung, dan baik yang diperoleh dari sumber lainnya, telah disertai keterangan mengenai identitas sumbernya dengan cara sebagaimana lazimnya dalam penulisan karya ilmiah. Dengan demikian walaupun tim penguji dan pembimbing penulisan skripsi/ tugas akhir/ final project ini membubuhkan tanda tangan keabsahannya, seluruh karya ilmiah ini tetap menjadi tanggung jawab saya sendiri. Demikian, harap pernyataan ini dapat digunakan seperlunya. Semarang, 7 Februari 2011 Yang membuat pernyataan Zico Muhardhiansyah iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to praise Allah SWT, the One and the Almighty, for his blessing, guidance that enable me to finish my final project. Secondly, I would sincerely like to express my deepest gratitude to Dwi Anggara A.S.S,M.Pd, as my first advisor and Maria Johana Ari W.S.S,M.Si, as my second advisor, for their invaluable advice, inspiring guidance, patience, time and encouragement throughout the process of finishing my final project. -

Yearone En.Pdf

1 Wallace Lee's RAMBO YEAR ONE Based on characters created by: David Morrell English Translation: Wallace Lee Mary Bottazzi Wall Street English,Vicenza Test reading: Mat Thomas Marchand Piero Costanzi Orazio Fusco Arianna De Angelis Website design by: Marco Faccio Cover art: Subject by Wallace Lee Photo by Marco Bizzotto Knife design by Jimmy Lile A Special Thank: To all of the veterans that contributed to this book; words aren't enough, guys. Thank you from the heart. Released by Double Edged Ghost Writings, 2015 [email protected] Copyright disclaimer: The characters of Rambo and Col. Sam Trautman were created by David Morrell in his novel First Blood, copyright 1972, 2015. All rights reserved. They are included here with the permission of David Morrell, provided that none of the story is offered for sale. The use of the characters here does not imply David Morrell's endorsement of the story. The First Blood knife was designed by Arkansas knifesmith Jimmy Lile (1982). Everything you read here that isn't mentioned in any official licensed Rambo movie or novel at the time of this publishing (2015), is an original work by the author of this book but is NOT covered by copyright. Electronic copy for private reading, freesharing and press evaluation only. No commercial use allowed. 2 Year One................................................................6 History episodes behind the Rambo movies......142 History episodes behind Year One.....................158 Trautman's opinion about the Vietnam war........166 Preview of the next work....................................174 3 HOW TO READ Sometimes this book uses a special way of reading that simulates the titles of the big screen, but this is meant to work only if you are reading (and so viewing) one page at a time. -

Rambo Et Ses Frères

!" ! # #$% &' !( )* + ( !(! & , ! -. //0 1- 2 134"5 *% 4$ ! )'" + ( !(! & , ! -. ! "# # 9 $ $ $ % & '()*) +'&, - $( .) ( & # # C /#/ % 01 2# .. C /#/#/ 0 1# .. 9/ /#/#3 . 455 4 " % 2 6 72 4" 8# . 9; /#3 5 6 " 8, "44 # .. 9@ /#3#/ 4 14 9 9 2 4# . 9@ /#3#3 . 41 : " % ; .. 9 & .< $ % .) $ ) *$=. , >> $ $.( - ) )# # # 0 3#/ 55" 0# .. ? 3#/#/ . 1 ! 00 # .. @ 3#/#3 . 4? 244# . C 3#3 . 2"? 5" # . ; 3#3#/ . 45 ; . ; 3#3#3 . 45 0 # . ;? $( $ % .) $ *) & )(), $ .$ & ).)( (.$ ( $)(# # # 9 @#/ "4 " 2 " 04 % 6 " "A 8 /BC # . @#/#/ 1 % " : "?1 "5 4 # . ; @#/#3 ( 1 % "?" # .. ? @#3 " 5D % 1 " # . C @#3#/ " % ?4 1 5 41 # . C @#3#3 " " % 5" 44# . 00 " % # 0C /BC 6 4 # 8 10? # # ?; " !6 2 . ?; " " 2 . ? )) < ( # ?0 ! ' . ?0 7 892 : " ! #6 - . ?0 7 82 : " ! #6 - . ?? 7 8; 2 : " ! #6 - ; . ?? 7 82 < = : # ! >. ?@ 7 802 < = : # ! 2 & >. ?@ 7 8?2 < . ?B 7 8@2 "A-. ?B 7 8B2 "A- . ?C 7 8C2 "A- . ?C 7 89/2 "A- . @/ 7 8992 "A- . @9 7 892 6 . .. @9 7 89; 2 & . @ D" ! ! E. @ 7 89 2 & !" !(6 ! &! E% / F6 9CB9. @ 7 8902 "! * <. @@ 7 89? 2 *. B9 7 89@ 2 D" ! &! E !6 (" ! 6E ,% B 9CB;. BC 7 89B 2 " ! (6 ! D' E,% ; 9CB;. C? 7 89C 2 D" ! &! E + & ! "% !% ? F 9CB. 9/ 7 8/ 2 D" ! &! E + 5 #"5% !% ? F 9CB. 9/0 7 89 2 4E + * , 7% / "< 9CB. 9/@ 7 8 2 "! !" !(6 ! &! E% 9 F6 9CB. 9/B 7 8; 2 < 6% ** * . 99; D , . 99C 7 8 2 #7 ''" "% 9CB/ G 9CC/ . 99C 7 80 2 7 ! "" ! &# * % 9CB/39CBC. 9 7 8? 2 7 ! *6% 9C@C39CBC. 9 7 8@ 2 ' *6 !("5% 9C@@39CBC. 90 7 8B2 #!E ! D' !'" <!E% 9CB939CBC. -

Baker En.Pdf

1 The unofficial Baker teams' insignia. It was an unofficial shoulder patch (designed by soldiers and hand-sewed by Saigon's tailors), and meant to be worn during conventional warfare only. CCN, CCC e CCS (Command and Control North, Central, South) were the three SOG's zones of operation. The two Baker teams were the only one purposely trained for operating in all the three sectors. The survival knife represents the reconnaissance nature of 'fighting behind enemy lines', using stealth, survival and self-reliance as their primary skills, which are also the reason the Baker teams were created for. The AK refers to the most clandestine operations ran by the two teams, which required the use of Russian weapons and uniforms in disguise. 2 BAKER TEAM 3 Wallace Lee's BAKER TEAM Based on characters created by: David Morrell English Translation: Wallace Lee Mary Bottazzi Test reading: Orazio Fusco Piero Costanzi Mat Thomas Marchand Rime Merln Website design by: Marco Faccio Cover art: Subject by Wallace Lee Patch drawing by Marco Faccio Photo by Marco Bizzotto Released by Double Edged Ghost Writings, 2016 [email protected] Copyright disclaimer: The characters of Rambo and Col. Sam Trautman were created by David Morrell in his novel First Blood, copyright 1972, 2017. All rights reserved. They are included here with the permission of David Morrell, provided that none of the story is offered for sale. The use of the characters here does not imply David Morrell's endorsement of the story. The First Blood knife was designed by Arkansas knife-smith Jimmy Lile (1982). -

The Soldier's Return: Films of the Vietnam War Michael James Noreen Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2004 The soldier's return: films of the Vietnam War Michael James Noreen Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noreen, Michael James, "The os ldier's return: films of the Vietnam War" (2004). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16165. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16165 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The soldier's return: films of the Vietnam War by Michael James Noreen A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Program of Study Committee: Charles L.P. Silet, Major Professor Leland Po ague Hamilton Cravens Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2004 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify thri{the master's thesis of Michael James Noreen has met the requirements of Iowa State University ... Major Professor For the Major Program 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. A CHANGING WAR 1 CHAPTER 2. COMBAT FILMS: THE GREEN BERETS, PLATOON, 5 FULL METAL JACKET, AND HAMBURGER HILL CHAPTER 3. THE SOLDIER'S RETURN 18 CHAPTER 4. THE WAR STILL REMAINS 47 ANNOTATED FILMOGRAPHY 50 WORKS CITED/WORKS CONSULTED 52 1 CHAPTER 1 A CHANGING WAR Beginning in the mid-1960s the Vietnam War became, for filmmakers, fertile ground in which to re-establish the war film genre. -

The Impact of the Cold War on the Representation of White Masculinity in Hollywood Film William Michael Kirkland

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 The Impact of the Cold War on the Representation of White Masculinity in Hollywood Film William Michael Kirkland Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE IMPACT OF THE COLD WAR ON THE REPRESENTATION OF WHITE MASCULINITY IN HOLLYWOOD FILM By WILLIAM MICHAEL KIRKLAND A Dissertation submitted to the Program in Interdisciplinary Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2009 The members of the committee approve the dissertation of William Michael Kirkland defended on November 19, 2009. ____________________________________ Maricarmen Martinez Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________________ Maxine Jones University Representative ____________________________________ Eugene Crook Committee Member ____________________________________ Ernest Rehder Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________________________ John Kelsay, Director, Program in Interdisciplinary Humanities The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii For Katina, whose love and support made this achievement possible. For my mother, Dianne Kirkland, whose memory I will always cherish. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I must thank my major professor, Dr. Maricarmen Martinez, for the guidance and encouragement she has provided since our first class together in fall 2003. Her support in times of discouragement and stress has been invaluable. I appreciate most the exchange of ideas that has taken place both in the classroom and throughout the dissertation process. Dr. Martinez, my teaching is better as a result of having worked with you. I wish to thank Dr. -

{PDF} First Blood 1St Edition Ebook Free Download

FIRST BLOOD 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Morrell | 9780446364409 | | | | | First Blood 1st edition PDF Book I read this before I saw the movie. While we're told about the horrors he experienced during his tour, none it ever manifests into his character, as all he ever does is run, shoot, kill, and throw-up. And setting the gas pumps on fire. I of course have lived, would not have been in favour of the Guerra of the Viet Nam would have considered it a mistake, but it would have attacked the excesses of the left in this campaign. Seven years after his discharge, Vietnam War veteran John Rambo travels by foot to visit an old comrade, only to learn that his friend had died from cancer the previous year, due to Agent Orange exposure during the war. I also told him despite my opposition to the Viet Nam war. The voice was starting to repeat, broke up, never came back again. Create a Want Tell us what you're looking for and once a match is found, we'll inform you by e-mail. He loves his job and cares about the men under his command. View 2 comments. Published by Armchair Dective, New York Thanks for telling us about the problem. Research Article October 6 Research Article September 24 The way he described what was happening in the book Personal Response: I found this book to be very action-packed and it had me on the edge of my seat to the last page. John Rambo. Then Rambo guts the cop coming at him with a straight razor.