THE IMAGE of REDEMPTION in Literature, Media, and Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biography Artistically Yours

Biography Artistically Yours Nathou, the skater athalie Deschênes put skates on for the first time when she was 9 years old. Her passion for figure skating was immediate. When she was in Secondary “You must always feel Four, she enrolled in a sport-academics program that allowed her to skate more movement, right to your Nfrequently. “If it were not for innocence, we would not be able to create such grand projects.” Everyone had a nickname while on the ice and Nathalie wanted an artist’s name. finger tips.” Out of the blue, her friend Isabelle Brasseur came up with the name Nathou. Since then, the name has followed her everywhere, even on Facebook where, after sharing her thoughts, she signs “Artistically yours . Nathou”. 2 Nathalie Deschênes — Choreographer — www.nathou.net Beautiful and vivacious, she is alive and allows us to experience different emotions . A bright future a rose... Trained by Josée Picard and Eric Gillis, she learned all the basics in order to become to inspire and interpret your a superior athlete. Technical skills, as well choreographies. as presentation and attitude on the ice, were part of Nathalie’s training in order to succeed. She practiced her technique and took 5th place in the junior pairs category at the 1991 Canadian championships. Brasseur and Lloyd Eisler, Josée Chouinard, At the age of 19, she changed trainers and Elvis Stojko and many others. She has also began concentrating on singles skating. skated on the ice while performers from Under the supervision of several trainers, the Cirque du Soleil executed their art. -

Kim Kardashian West Is Giving Away $500 Each to 1,000 People

12 Established 1961 Lifestyle Features Wednesday, December 23, 2020 Employees of the Saless publishing house pose for a group Employees of the Yassavoli Publications pose for a group Employee Sepideh Daryan checks a bestselling book at a Iranian bookseller Mehrani poses for a picture at a book- picture with bestselling books in Iran’s capital Tehran. picture with bestselling books in Iran’s capital Tehran. bookstore of the Nashre-Cheshmeh Publishing House on store in Tehran’s Enqelab (Revolution) street. Karim Khan street. — AFP photos rench authors Albert Camus and censorship is present in Iranian publish- books has made them increasingly pro- Simone de Beauvoir rub shoulders ing, it affects mainly content deemed hibitive for some. In a country were some Fwith the likes of Jewish diarist Anne licentious, and many Western best-sellers ultraconservative leaders regularly deny Frank and Russian poet Osip Mandelstam are quickly translated and made available the reality of the Holocaust, Javad Rahimi, in Tehran bookstores where the largely in Iran, where copyright is not recognized. salesman at the Sales bookstore, noted female readership lap up foreign writers. Karim Khan, along with Enqelab the recent success of the “Tattooist of “Iranian women read more, translate more (Revolution) street, is one of two roads in Auschwitz”, by New Zealand writer and write more. In general, they are more central Tehran that readers flock to, Heather Morris, and “The Diary of Anne present in the book market than men,” known for being chockablock with book- Frank”, by the young Jewish girl from said Nargez Mossavat, editorial director shops. -

The Daily Egyptian, June 16, 1988

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC June 1988 Daily Egyptian 1988 6-16-1988 The aiD ly Egyptian, June 16, 1988 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_June1988 Volume 74, Issue 156 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, June 16, 1988." (Jun 1988). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1988 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in June 1988 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Daily Egyptian Southern Illinois University at Carbondale Thursday, June 16,1988, Vol. 74, No. 156, Page 12 Reagan again urges aid for Contras WASHINGTON (uPI) - Nicaragua do have a force here and what we're going to rebels - a cornerstone of the Sandinistas are not going to President Reagan, putting there that can be used to bring do," Reagan said. president's foreign policy. democratize ... and it seems to part of the blame on Congress about an equitable set But asked if he thinks it is White House spoiresman me that the efforts that have for the collapsed peace talks in tlement." time for m9re military aid for Marlin Fitzwater said no been made in CongrelS and Nicaragua, said Wednesday But Reagan refused to say if the rebels, Reagan said, "I decision was made on a new succeeded i.'1 reducing and the need for Military aid for or when he would actually think it is so apparent that that funding request though con eliminating our ability to help the Contra rebels is now "so submit an aid package - is what is necessary it woold suHations were continuing. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS 2415 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS INSURANCE CRISIS Sports

February 23, 1988 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 2415 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS INSURANCE CRISIS sports. It's part of the lawsuit crisis. Our BIGBY. Well when I tried to open the door, cities are in a bind. Money needed for fire it would not open. fighters, police, and other services is being BRADLEY. According to the sworn testimo HON. AL SWIFT used to pay the price of the lawsuit crisis. ny of an eyewitness that is exactly what OF WASHINGTON New York City says lawsuits may soon cost happened. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES as much as the Fire Department. BIGBY. He said that "the last thing he saw BRADLEY. Well, what about it? For open Tuesday, February 23, 1988 Mr. Bigby doing was pulling at the door, ers, leading experts on manpower shortages struggling to get out." That was just before Mr. SWIFT. Mr. Speaker, I would like to in medicine tell us lawsuits are causing no the car impact, and hit the phone booth. share with my colleagues a transcript from a shortages of obstetrical services now, nor BRADLEY. You're aware of what President recent "60 Minutes" program that took a criti will they in the foreseeable future. About Reagan has said about ... about your case? cal look into some of the anecdotal evidence high school sports, for the last seven years BIGBY. They're saying that my case is out we've found just six successful lawsuits used by the insurance industry to make their rageous. But he doesn't tell them that the against schools sports programs. -

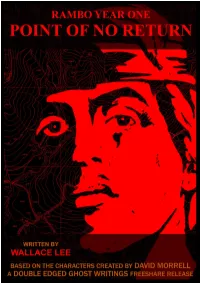

Point of No Return

1 Wallace Lee's POINT OF NO RETURN Based on characters created by: David Morrell Test reading: Piero Costanzi Orazio Fusco Flavio Brio Gary Rhoac Mat Thomas Marchand Italian language editing by: Flavio Brio Website Design by: Marco Faccio Cover by: Marco Faccio from a drawing by Ambra Rebecchi and a concept by Wallace Lee a very special thanks To all of the veterans that helped me with this, ..words are not enough. Thank you from the bottom of my heart. Double Edged Ghost Writings, 2017 [email protected] Copyright: Copyright disclaimer: The characters of Rambo and Col. Sam Trautman were created by David Morrell in his novel First Blood, copyright 1972, 2017. All rights reserved. They are included here with the permission of David Morrell, provided that none of the story is offered for sale. The use of the characters here does not imply David Morrell's endorsement of the story. The First Blood knife was designed by Arkansas knife-smith Jimmy Lile (1982). Everything you read here that is not mentioned in any official licensed Rambo movie or novel at the time of this publishing (2017), is an original work by the author. Electronic copy for private reading, free sharing and press evaluation only. No commercial use allowed. 2 POINT OF NO RETURN 3 IMAGES 4 Here, we can see a reconnaissance team made up of both indigenous and American personnel sporting long-range equipment only moments after returning home from their last mission. 5 This picture shows an example of emergency stepladder use. Oftentimes, rescuing an SOG team was an extremely precarious feat and needed a quick rescue like the one only a stepladder could offer. -

Orser, Brian (B

Orser, Brian (b. 1961) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2008 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Brian Orser carrying the Canadian flag at the Olympian Brian Orser, known for both his athleticism and artistry, led a resurgence of opening ceremonies of Canada as a force to be reckoned with in men's figure skating, a situation that the the Calgary Olympic games in 1988. country had not enjoyed since the glory days of Toller Cranston. Photograph by Ted Grant. Like many young Canadians, Brian Orser, born December 18, 1961 in Belleville, Image courtesy Library Ontario, put on skates at an early age. As a child he played hockey but was more and Archives Canada, © drawn to figure skating. His first pair of figure skates were hand-me-downs from one Library and Archives Canada. of his older sisters. He painted them over from white--then the compulsory color for women--to black, then required for men. Orser first appeared in a skating carnival at the age of six and did his first solo performance two years later. Orser advanced through the ranks of Canadian junior skating, combining artistry with outstanding athletic ability. In 1979 he became the first junior and only the second person to land a triple axel in competition. He would later achieve distinction by becoming the first to perform a triple axel in combination. Orser won his first medal at the World Championships--a bronze--in 1983. In the Olympic Games of 1984 in Sarajevo he skated for silver. When the Olympics opened in Calgary in 1988, Orser was honored by being chosen to lead the Canadian delegation as flag-bearer. -

Politics of Sly� Neo-Conservative Ideology in the Cinematic Rambo Trilogy: 1982-1988

Politics of Sly Neo-conservative ideology in the cinematic Rambo trilogy: 1982-1988 Guido Buys 3464474 MA Thesis, American Studies Program, Utrecht University 20-06-2014 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Theoretical Framework ........................................................................... 12 Popular Culture ............................................................................................................................................ 13 Political Culture ........................................................................................................................................... 16 The Origins Of Neo-Conservatism ....................................................................................................... 17 Does Neo-Conservatism Have A Nucleus? ....................................................................................... 20 The Neo-Conservative Ideology ........................................................................................................... 22 Chapter 2: First Blood .................................................................................................... 25 The Liberal Hero ......................................................................................................................................... 26 The Conservative Hero ............................................................................................................................ -

New Members Received May 20, 2018

Increasing Our Love for God & Neighbor HighlightTHE CONGREGATIONAL UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST St. Charles (Campton Hills) • cuccstc.org May 3, 2018 • Issue 4 SEM’s to Return We are relaunching our church’s SEM (Summer Experience in Ministry) internship program! We’re very enthusiastic about this opportunity and confident that it will be a rich experience for the participants. The SEM interns, guided by the pastors, will join a program of action and reflection, sharing work and conversation with one another, and with children, youth, and adults of the church, exploring both “what we believe” and “how we live our faith.” SEM interns will be challenged to develop their own practical theology. There will be specific projects in ministry, occasions for leadership, invitations to be creative, chances for recreation and, every week, a conversation about what we’re learning. The SEM internship is open to CUCC members who are post-secondary students, graduating high school seniors through college. If you know of anyone who would be interested in applying for this opportunity, or have any questions, feel free to contact us directly. Grace and peace, The Rev. David Pattee The Rev. Josh Kuipers Senior Pastor Associate Pastor [email protected] [email protected] New Members Received May 20, 2018 Contact the church office if you ‘d like to be added to the list. To Members of the Church, Pray for each other so I want to thank you all who sent cards and encouraging that you may be healed.... words of hope to me during complications from knee surgery. -

Kardashian Konfidential: New! Inside Kim's Wedding with Never-Seen Pix, Plus a New Chapter!

[PDF] Kardashian Konfidential: New! Inside Kim's Wedding With Never-Seen Pix, Plus A New Chapter! Kim Kardashian, Kourtney Kardashian, Khloe Kardashian - pdf download free book Kardashian Konfidential: New! Inside Kim's Wedding With Never-Seen Pix, Plus A New Chapter! PDF Download, Kardashian Konfidential: New! Inside Kim's Wedding With Never-Seen Pix, Plus A New Chapter! by Kim Kardashian, Kourtney Kardashian, Khloe Kardashian Download, Free Download Kardashian Konfidential: New! Inside Kim's Wedding With Never-Seen Pix, Plus A New Chapter! Ebooks Kim Kardashian, Kourtney Kardashian, Khloe Kardashian, Read Kardashian Konfidential: New! Inside Kim's Wedding With Never-Seen Pix, Plus A New Chapter! Full Collection Kim Kardashian, Kourtney Kardashian, Khloe Kardashian, Kardashian Konfidential: New! Inside Kim's Wedding With Never-Seen Pix, Plus A New Chapter! Full Collection, Read Best Book Online Kardashian Konfidential: New! Inside Kim's Wedding With Never-Seen Pix, Plus A New Chapter!, Kardashian Konfidential: New! Inside Kim's Wedding With Never-Seen Pix, Plus A New Chapter! Free Read Online, Download PDF Kardashian Konfidential: New! Inside Kim's Wedding With Never-Seen Pix, Plus A New Chapter! Free Online, read online free Kardashian Konfidential: New! Inside Kim's Wedding With Never-Seen Pix, Plus A New Chapter!, Kim Kardashian, Kourtney Kardashian, Khloe Kardashian epub Kardashian Konfidential: New! Inside Kim's Wedding With Never-Seen Pix, Plus A New Chapter!, Kim Kardashian, Kourtney Kardashian, Khloe Kardashian ebook Kardashian -

The Kardashians and the Ruminating Strategy

Sociology Study, July 2018, Vol. 8, No. 7, 345‐350 D doi: 10.17265/2159‐5526/2018.07.005 DAVID PUBLISHING The Kardashians and the Ruminating Strategy Claudia Lisa Moellera Abstract Many have wondered in these years about the reason behind the huge success the Kardashian (‐Jenner) family raised and gained. Even if the reality show might not be one of the most innovative, nor original television products, it is impossible to see how the Kardashian’s clan managed to become something more than a family who likes to air their dirty (and maybe expansive) laundry in public. Albeit there are different reality shows that have portrayed almost every possible family: religious, heavy metal, gipsy, wealthy Californian, dysfunctional, party animals; the Kardashians celebrated in 2018 their 10 years of reality shows. This might appear a silly, and not even a big deal: TV shows have existed for longer time in the American (and not only) panorama, yet the Kardashian made it possible to conquest with their unique style, and communication strategy something that other reality shows families did not reach. What did the Kardashians do? The Kardashians created a new communication strategy that allowed them to be the most popular family on three different media: press, television, and social media. Keywords Kardashian, Søren Kierkegaard, hermeneutics of television, internet and television, reality shows The Kardashians forged a new type of communication Indeed, the Kardashians’ material is rarely new. strategy that involves different media, in which every The ability of this family and the key of their success media explains and gives different elements to rely on the ability to use and re-use the same material understand part of the story that another media has and stories all over again. -

Barnett Objects to Subsidy, Water Line, Other Issues

SPORTS: LCC WRESTLING COACH RENFRO TALKS ABOUT REST OF SEASON. PAGE 5 ParsonsSun FRIDAY, JAN. 4, 2013 — 75 CENTS www.parsonssun.com LOCAL NEWS Barnett objects PFD answers two fi re calls to subsidy, water The Parsons Fire Depart- menthasremainedbusyinthe new year, responding to two structurefiresinthefirsttwo line, other issues daysof2013. The department received a callat5:53p.m.Wednesday BY JAMIE WILLEY TomShawsaidchildrenplaygolf [email protected] about a fire at 1403 S. 23rd. also, and Commissioner Kevin Crusesaidthecityfundsaswim- When firefighters arrived, A$12,000subsidyfortheKaty heavysmokeandflameswere ming pool, ball parks, disc golf, GolfClubledtoadiscussionabout parksandmanyotherrecreational shooting from the southern thecity’sprioritiesduringthePar- portionoftheroofofahome opportunitiesaswellasgolf.City sonsCityCommission’sThursday ManagerFredGresssaidgolfim- ownedbyJohnHarlander.The afternoonworksession. homewasunderrenovation, provesthequalityoflifeforthecity Commissioner Frankie Bar- andmanyemployersexpectthere accordingtoareportfromthe nettstartedbyquestioningthe firedepartment.Thehouse tobeagolfcoursehere. subsidybutalsotalkedaboutsev- wasvacant,andJeffAllenwas Barnett mentioned water eralotherthingsthecityneeds, thelocalcontactforthehouse. parksinIndependenceandCha- ranging from more infrastruc- Thehousewasatotalloss, nute that his grandchildren go turerepairtomorerecreational withdamagesexceeding to,andhesaidhehasseenmany $25,000. The fire seemed to opportunitiesforchildren. peoplefromParsonsattheparks. havestartedintheatticofthe -

Missives TMZ Executive Producer, Evan Rosenblum Interview with a Celebrity Interviewer

Malibu MISSIVES TMZ Executive Producer, Evan Rosenblum Interview with a Celebrity Interviewer TMZ, a relative newcomer, began in 2005 as the brainchild of Harvey Levin… you know, the “I’m a Lawyer” guy. TMZ made its way onto TV in 2007. For those who may have forgotten, “TMZ” is short for “The Thirty Mile Zone”; or Hol- lywood Producer short-speak for the 30-mile radius within which most Hollywood movie production occurs and the distance after which extra crew fees and travel expenses kick-in. While it’s described as a Celebrity Gossip, Entertain- ment and Celebrity News organization, I wouldn’t relegate TMZ to merely gossip news coverage. Almost immediately after launching, TMZ began earning its bones as journalists. TMZ is credited with breaking such global news as the Michael Jackson investigations and most tragically broke the news of Michael Jackson’s demise; as well as, the many times difficult-to-watch Donald Sterling-Clippers debacle. TMZ created its own sometimes tongue- in-cheek, good-humored, unique Entertainment News coverage style and format; at which many would agree they remain the best. Recently, I was able to speak with Evan Rosenblum, an Executive Producer at TMZ and TMZ Hollywood Sports where he also performs double-duty as its lead host. Evan has been with Harvey Levin from the beginning. He started as an intern while still pursuing his undergraduate degree in Journalism from Arizona State University. In a very short period, Evan has come a long way. During our conversation, I learned that Evan is credited with breaking some of TMZ’s biggest stories.