Wounded Warriors: Contemporary Representations of Soldiers' Suffering by Alison M Bond a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Daily Egyptian, June 16, 1988

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC June 1988 Daily Egyptian 1988 6-16-1988 The aiD ly Egyptian, June 16, 1988 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_June1988 Volume 74, Issue 156 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, June 16, 1988." (Jun 1988). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1988 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in June 1988 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Daily Egyptian Southern Illinois University at Carbondale Thursday, June 16,1988, Vol. 74, No. 156, Page 12 Reagan again urges aid for Contras WASHINGTON (uPI) - Nicaragua do have a force here and what we're going to rebels - a cornerstone of the Sandinistas are not going to President Reagan, putting there that can be used to bring do," Reagan said. president's foreign policy. democratize ... and it seems to part of the blame on Congress about an equitable set But asked if he thinks it is White House spoiresman me that the efforts that have for the collapsed peace talks in tlement." time for m9re military aid for Marlin Fitzwater said no been made in CongrelS and Nicaragua, said Wednesday But Reagan refused to say if the rebels, Reagan said, "I decision was made on a new succeeded i.'1 reducing and the need for Military aid for or when he would actually think it is so apparent that that funding request though con eliminating our ability to help the Contra rebels is now "so submit an aid package - is what is necessary it woold suHations were continuing. -

Montana Kaimin, May 24, 1974 Associated Students of the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 5-24-1974 Montana Kaimin, May 24, 1974 Associated Students of the University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the University of Montana, "Montana Kaimin, May 24, 1974" (1974). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 6274. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/6274 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Friday,montana May 24, 1974 • Missoula, Montana • Voi. 76, No. 104 KAIMIN Newsmen chosen to question Children more vulnerable to pollution Three newsman were chosen yester made Wednesday by Williams, who Helena AP technology is not only available for day by KGVO-TV, Missoula to ask challenged his two opponents to be combines with other pollutants in the Children at play are more vulnerable Anaconda to comply with the Mon the questions in the televised debate public debate on the issues several air. than adults to disease caused by air tana standards, but the methods of between Western District Congres weeks ago. Olsen and Baucus later pollution, such as emissions from the Control of sulfur oxides would be*a pollution control have been proven sional Democratic candidates Pat accepted the challenge. -

More Is More Brochure Cropped

forEword What is the difference between a graphic designer and a “fine artist,” between he who gives highway signs their typeface and she whose canvasses and sculptures live in museums where admission must be paid? In terms of talent, possibly none. The difference is one of intimacy. We gaze up at our favorite paintings, gingerly circumnavigate the greatest sculptures—we literally put them on pedestals. But we hug our favorite books and records, and kiss their covers, and a particular typeface will forever conjure the road-sign at the turnoff to the summer lodge, that last turn that led to nirvana, the last week of August, the summer after tenth grade. I don’t want to meet the artist (the painter, the sculptor, the violin prodigy, the rock star), for if I did, she’d probably disappoint, and if she didn’t, I’d be tongue-tied. But the graphic designer? I want to clasp him to me, and ask how he did it, and say Thank you. No need to invite George Corsillo into your living room and offer him a nip or a puff—he’s been there all along. He’s been in your album crate since the early 1980s, showcasing John and Olivia at their Grease-iest, Luther Vandross at his sultriest, Benatar, Mellencamp, Yoko. In his toolbox, George always brings his analog chops, learned with the legendary book-jacket designer Paul Bacon; nobody has that facility with typeface or silkscreening who grew up only on computers. He brings, too, a party- down fierceness, a willingness to get his hands dirty (on the Grease jacket, those are George’s teeth marks on the pencil), a scavenger’s resourcefulness (the legs on the Tilt cover? his wife, Susan’s), and a tactful deference to the artist, masking, as needed, Vandross’s girth or Benatar’s pregnancy. -

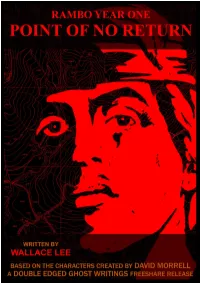

Point of No Return

1 Wallace Lee's POINT OF NO RETURN Based on characters created by: David Morrell Test reading: Piero Costanzi Orazio Fusco Flavio Brio Gary Rhoac Mat Thomas Marchand Italian language editing by: Flavio Brio Website Design by: Marco Faccio Cover by: Marco Faccio from a drawing by Ambra Rebecchi and a concept by Wallace Lee a very special thanks To all of the veterans that helped me with this, ..words are not enough. Thank you from the bottom of my heart. Double Edged Ghost Writings, 2017 [email protected] Copyright: Copyright disclaimer: The characters of Rambo and Col. Sam Trautman were created by David Morrell in his novel First Blood, copyright 1972, 2017. All rights reserved. They are included here with the permission of David Morrell, provided that none of the story is offered for sale. The use of the characters here does not imply David Morrell's endorsement of the story. The First Blood knife was designed by Arkansas knife-smith Jimmy Lile (1982). Everything you read here that is not mentioned in any official licensed Rambo movie or novel at the time of this publishing (2017), is an original work by the author. Electronic copy for private reading, free sharing and press evaluation only. No commercial use allowed. 2 POINT OF NO RETURN 3 IMAGES 4 Here, we can see a reconnaissance team made up of both indigenous and American personnel sporting long-range equipment only moments after returning home from their last mission. 5 This picture shows an example of emergency stepladder use. Oftentimes, rescuing an SOG team was an extremely precarious feat and needed a quick rescue like the one only a stepladder could offer. -

Politics of Sly� Neo-Conservative Ideology in the Cinematic Rambo Trilogy: 1982-1988

Politics of Sly Neo-conservative ideology in the cinematic Rambo trilogy: 1982-1988 Guido Buys 3464474 MA Thesis, American Studies Program, Utrecht University 20-06-2014 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Theoretical Framework ........................................................................... 12 Popular Culture ............................................................................................................................................ 13 Political Culture ........................................................................................................................................... 16 The Origins Of Neo-Conservatism ....................................................................................................... 17 Does Neo-Conservatism Have A Nucleus? ....................................................................................... 20 The Neo-Conservative Ideology ........................................................................................................... 22 Chapter 2: First Blood .................................................................................................... 25 The Liberal Hero ......................................................................................................................................... 26 The Conservative Hero ............................................................................................................................ -

Dilbert": a Rhetorical Reflection of Contemporary Organizational Communication

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1998 "Dilbert": A rhetorical reflection of contemporary organizational communication Beverly Ann Jedlinski University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Jedlinski, Beverly Ann, ""Dilbert": A rhetorical reflection of contemporary organizational communication" (1998). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 957. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/3557-5ql0 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS Uns manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI fifans the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter free, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afifrct reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these wiH be noted. -

Tanner ’88, K-Street, and the Fictionalization of News

Rethinking the Informed Citizen in an Age of Hybrid Media Genres: Tanner ’88, K-Street, and the Fictionalization of News By Robert J. Bain Jr. B.A. Biology B.A. Philosophy Binghamton University, 2000. Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2004 © 2004 Robert J. Bain Jr. All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author………………………………………………………………………… Program in Comparative Media Studies May 17, 2004 Certified by………………………………………………………………………………… Henry Jenkins III Director, Program in Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted by ……………………………………………………………………………….. Henry Jenkins III Director, Program in Comparative Media Studies 1 PAGE TWO IS BLANK 2 Rethinking the Informed Citizen in an Age of Hybrid Media Genres: Tanner ’88, K-Street, and the Fictionalization of News By Robert J. Bain Jr. Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies on May 17, 2004 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT A close reading of two television shows, K-Street and Tanner ’88, was performed to examine how one might become informed about real-life political news by viewing entertainment programs that combine fiction with actual current political events, issues, and figures. In his book The Good Citizen, Michael Schudson claims that mere factual recall does not necessarily indicate that one is “informed”, but rather an “informed citizen” is one who actively reads the “information environment”. -

First Blood Vendetta

FIRST BLOOD: VENDETTA Written by Gary Patrick Lukas Based on the characters by David Morrell. In his fifth action packed installment, Rambo finally goes home, only to find his father isn't the only one glad to see him back, but for different reasons of course. [email protected] WGA Registration: I245270 Copyright(c)2012 This screenplay may not be used or reproduced without the express written permission of the author. FADE IN: To a piano accompaniment of “IT’S A LONG ROAD”. EXT. ROUTE 66 - DAY In b.g. a distant figure simmering and wavering in the heat haze of the day. In the f.g. is a ROAD SIGN ‘Route 66’ CREDIT SEQUENCE - EARLY MORNING A LONELY FIGURE walks the old highway alone, with the occasional car WHIZZING past him. He is wearing an old 70s style army jacket and a large backpack is slung over his shoulder. His hair is long and unkempt. His name is JOHN RAMBO! Rambo hears a CAR pull up behind him and turns. CU. ON CAR DOOR to see that it’s a police car for Navajo county. It is slowly accompanying Rambo as he is walking by the side of the road. Rambo is getting nervous. PAUSE CREDITS The window goes down and a head pokes out. The head belongs to a deputy called WEAVER. WEAVER Hey Buddy. Wanna ride? RAMBO (hesitant) Eh... It’s OK officer. Just passing through. WEAVER Holbrook is still about 10 miles up ahead. Let me do my good deed for the day and take you to town. -

TV Outside The

1 ALPHA HOUSE on Amazon Elliot Webb: Executive Producer As trailblazers in the television business go, Garry Trudeau, the iconic, Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist/creator of Doonesbury, has an unprecedented track record. In 1988, Trudeau wrote and co-produced (with director Robert Altman) the critically acclaimed, political mockumentary Tanner ’88 for HBO. It was HBO’s first foray into the original scripted TV business, albeit for a limited series. (9 years later, in 1997, Oz became HBO’s first scripted drama series.) Tanner ’88 won an Emmy Award and 4 cable ACE Awards. 25 years later, Trudeau created Alpha House—which holds the distinction of being the very first original series on Amazon. The single-camera, half-hour comedy orbits around the exploits of four Republican senators (played by John Goodman, Clark Johnson, Matt Malloy, and Mark Consuelos) who live as roommates in the same Capitol Hill townhouse. The series was inspired by actual Democratic congressmen/roomies: Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL), Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY), and Representative George Miller (D-CA). Bill Murray did 2 cameos as hapless Senator Vernon Smits. Other real life politicians appeared throughout the series’ 2- season run. The series follows in the footsteps of Lacey Davenport (the Doonesbury Republican congresswoman from San Francisco), and presidential candidate Jack Tanner (played by Michael Murphy). All of Trudeau’s politicians are struggling to reframe their platforms and priorities while their parties are in flux. I think it’s safe to say that the more things change in Washington, the more things stay the same. Trudeau explores identity crises through his trademark trenchant humor. -

The Richard S. Salant Lecture

THE RICHARD S. S ALANT LECTURE ON FREEDOM OF THE PRESS WITH ANTHONY LEWIS The Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University 79 John F. Kennedy Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 2008 61 7-495-8269 • www.shorensteincenter.org THE RICHARD S. S ALANT LECTURE ON FREEDOM OF THE PRESS WITH ANTHONY LEWIS 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS History of the Richard S. Salant Lecture ............................................................ 5 Biography of Anthony Lewis ................................................................................ 7 Welcoming Remarks by Dean David Ellwood .................................................. 9 Introduction by Alex S. Jones .............................................................................. 10 The 2008 Richard S. Salant Lecture on Freedom of the Press by Anthony Lewis ............................................................................................ 12 THE RICHARD S. S ALANT LECTURE 3 HISTORY In 2007, the estate of Dr. Frank Stanton, former president of CBS, provided funding for a lecture in honor of his longtime friend and colleague, Mr. Richard S. Salant, a lawyer, broadcast media executive, ardent defender of the First Amendment and passionate leader of broadcast ethics and news standards. Frank Stanton was a central figure in the development of tele - vision broadcasting. He became president of CBS in January 1946, a position he held for 27 years. A staunch advocate of First Amendment rights, Stanton worked to ensure that broad - cast journalism received protection equal to that received by the print press. In testimony before a U.S. Congressional committee when he was ordered to hand over material from an investigative report called “The Selling of the Pentagon,” Stanton said that the order amounted to an infringement of free speech under the First Amendment. -

'Colossus' Was a 'Prophet'

8A Tuesday, May 18, 2010 Opinion ... Standard-Examiner Lee Carter, Andy Howell, Ron Thornburg, Doug Gibson, Publisher Executive Editor Editor, News & Circulation Editorial Page Editor Aluminum coins, anyone? ost Americans have no But this administration is talking as idea that some of that if cheaper-minted coins will happen change we jingle in our sooner instead of later, so perhaps we Mpockets or grab from our need to start a debate over what cheap- purse is a losing proposition for Uncle er ingredients to use in coins. The most Sam. notable shift in coinage was steel pen- Yes, it costs 9 nies used for cents to create a Perhaps it’s time for a cost-ef- a while during 5-cent nickle and World War II, almost 2 cents to fective change to our U.S. coins when other in- create a penny. that does not rob our money of gredients were Perhaps it’s its quality look and feel. in short supply. time for a cost- It seems hard effective change to believe that to our U.S. coins some type of that does not rob our money of its qual- metal-like surface would ever be aban- ity look and feel. doned for U.S. coins. Although plastic According to the Treasury Depart- tokens are used in the U.S. for transit ment, if we minted coins in a more and even for money in some countries, cost-effective manner, it could save we can’t imagine Americans tolerating taxpayers more than $100 million a plastic coins, or coins made of metal year. -

Commencement1990.Pdf (7.862Mb)

TheJohns Hopkins University Conferring of Degrees At the Close of the 1 14th Academic Year May 24, 1990 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/commencement1990 Contents Order of Procession 1 Order of Events 2 Honorary Degree Citations 9 Academic Regalia 16 Awards 18 Honor Societies 22 Student Honors 25 Degree Candidates 28 Order of Procession MARSHALS Stephen R. Anderson Marion C. Panyan Andrew S. Douglas Peter B. Petersen Elliott W. Galkin Edward Scheinerman Grace E. Goodell Henry M. Seidel Sharon S. Krag Stella Shiber Bonnie J. Lake Susan Wolf Bruce D. Marsh Eric D. Young THE GRADUATES MARSHALS Jerome Kruger Dean W. Robinson THE FACULTIES to MARSHALS Frederic Davidson AJ.R. Russell-Wood THE DEANS OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY THE TRUSTEES CHIEF MARSHAL Owen M. Phillips THE PRESIDENT OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY ALUMNI COUNCIL THE CHAPLAINS THE PRESENTERS OF THE HONORARY DEGREE CANDIDATES THE HONORARY DEGREE CANDIDATES THE INTERIM PROVOST OF THE UNIVERSITY THE GOVERNOR OF THE STATE OF MARYLAND THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNIVERSITY - /- Order ofEvents Si even Muller President of the University, presiding * • 4 PRELUDE La Mourisque Tielman Susato (? -1561) Basse Dance Tielman Susato (? -1561) Two Ayres for Cornetts and Sagbuts JohnAdson (?- 1640) Sonata No. 22 Johann Pezel (1639-1694) » PROCESSIONAL The audience is requested to stand as the Academic Procession moves into the area and to remain standing after the Invocation. FESTIVAL MARCHES THE PRESIDENTS PROCESSION Fanfare Walter Piston (1894-1976) Pomp and Circumstance March No.