The Fossil Record of Tadpoles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Vertebrate Fossils from the Middle Eocene Oil Shale of Messel, Germany: Implications for Their Taphonomy and Palaeoenvironment

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 416 (2014) 92–109 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Isotope compositions (C, O, Sr, Nd) of vertebrate fossils from the Middle Eocene oil shale of Messel, Germany: Implications for their taphonomy and palaeoenvironment Thomas Tütken ⁎ Steinmann-Institut für Geologie, Mineralogie und Paläontologie, Universität Bonn, Poppelsdorfer Schloss, 53115 Bonn, Germany article info abstract Article history: The Middle Eocene oil shale deposits of Messel are famous for their exceptionally well-preserved, articulated 47- Received 15 April 2014 Myr-old vertebrate fossils that often still display soft tissue preservation. The isotopic compositions (O, C, Sr, Nd) Received in revised form 30 July 2014 were analysed from skeletal remains of Messel's terrestrial and aquatic vertebrates to determine the condition of Accepted 5 August 2014 geochemical preservation. Authigenic phosphate minerals and siderite were also analysed to characterise the iso- Available online 17 August 2014 tope compositions of diagenetic phases. In Messel, diagenetic end member values of the volcanically-influenced 12 Keywords: and (due to methanogenesis) C-depleted anoxic bottom water of the meromictic Eocene maar lake are isoto- Strontium isotopes pically very distinct from in vivo bioapatite values of terrestrial vertebrates. This unique taphonomic setting al- Oxygen isotopes lows the assessment of the geochemical preservation of the vertebrate fossils. A combined multi-isotope Diagenesis approach demonstrates that enamel of fossil vertebrates from Messel is geochemically exceptionally well- Enamel preserved and still contains near-in vivo C, O, Sr and possibly even Nd isotope compositions while bone and den- Messel tine are diagenetically altered. -

The World at the Time of Messel: Conference Volume

T. Lehmann & S.F.K. Schaal (eds) The World at the Time of Messel - Conference Volume Time at the The World The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 2011 Frankfurt am Main, 15th - 19th November 2011 ISBN 978-3-929907-86-5 Conference Volume SENCKENBERG Gesellschaft für Naturforschung THOMAS LEHMANN & STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL (eds) The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference Frankfurt am Main, 15th – 19th November 2011 Conference Volume Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung IMPRINT The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Conference Volume Publisher PROF. DR. DR. H.C. VOLKER MOSBRUGGER Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Editors DR. THOMAS LEHMANN & DR. STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected]; [email protected] Language editors JOSEPH E.B. HOGAN & DR. KRISTER T. SMITH Layout JULIANE EBERHARDT & ANIKA VOGEL Cover Illustration EVELINE JUNQUEIRA Print Rhein-Main-Geschäftsdrucke, Hofheim-Wallau, Germany Citation LEHMANN, T. & SCHAAL, S.F.K. (eds) (2011). The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates. 22nd International Senckenberg Conference. 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main. Conference Volume. Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, Frankfurt am Main. pp. 203. -

BOA2.1 Caecilian Biology and Natural History.Key

The Biology of Amphibians @ Agnes Scott College Mark Mandica Executive Director The Amphibian Foundation [email protected] 678 379 TOAD (8623) 2.1: Introduction to Caecilians Microcaecilia dermatophaga Synapomorphies of Lissamphibia There are more than 20 synapomorphies (shared characters) uniting the group Lissamphibia Synapomorphies of Lissamphibia Integumen is Glandular Synapomorphies of Lissamphibia Glandular Skin, with 2 main types of glands. Mucous Glands Aid in cutaneous respiration, reproduction, thermoregulation and defense. Granular Glands Secrete toxic and/or noxious compounds and aid in defense Synapomorphies of Lissamphibia Pedicellate Teeth crown (dentine, with enamel covering) gum line suture (fibrous connective tissue, where tooth can break off) basal element (dentine) Synapomorphies of Lissamphibia Sacral Vertebrae Sacral Vertebrae Connects pelvic girdle to The spine. Amphibians have no more than one sacral vertebrae (caecilians have none) Synapomorphies of Lissamphibia Amphicoelus Vertebrae Synapomorphies of Lissamphibia Opercular apparatus Unique to amphibians and Operculum part of the sound conducting mechanism Synapomorphies of Lissamphibia Fat Bodies Surrounding Gonads Fat Bodies Insulate gonads Evolution of Amphibians † † † † Actinopterygian Coelacanth, Tetrapodomorpha †Amniota *Gerobatrachus (Ray-fin Fishes) Lungfish (stem-tetrapods) (Reptiles, Mammals)Lepospondyls † (’frogomander’) Eocaecilia GymnophionaKaraurus Caudata Triadobatrachus Anura (including Apoda Urodela Prosalirus †) Salientia Batrachia Lissamphibia -

Arachnida: Araneae) from the Middle Eocene Messel Maar, Germany

Palaeoentomology 002 (6): 596–601 ISSN 2624-2826 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pe/ Short PALAEOENTOMOLOGY Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press Communication ISSN 2624-2834 (online edition) PE https://doi.org/10.11646/palaeoentomology.2.6.10 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:E7F92F14-A680-4D30-8CF5-2B27C5AED0AB A new spider (Arachnida: Araneae) from the Middle Eocene Messel Maar, Germany PAUL A. SELDEN1, 2, * & torsten wappler3 1Department of Geology, University of Kansas, 1475 Jayhawk Boulevard, Lawrence, Kansas 66045, USA. 2Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK. 3Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt, Friedensplatz 1, 64283 Darmstadt, Germany. *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] The Fossil-Lagerstätte of Grube Messel, Germany, has Thomisidae and Salticidae (Schawaller & Ono, 1979; produced some of the most spectacular fossils of the Wunderlich, 1986). The Pliocene lake of Willershausen, Paleogene (Schaal & Ziegler, 1992; Gruber & Micklich, produced by solution of evaporites and subsequent collapse, 2007; Selden & Nudds, 2012; Schaal et al., 2018). However, has produced some remarkably preserved arthropod fossils few arachnids have been discovered or described from this (Briggs et al., 1998), including numerous spider families: World Heritage Site. An araneid spider was reported by Dysderidae, Lycosidae, Thomisidae and Salticidae (Straus, Wunderlich (1986). Wedmann (2018) reported that 160 1967; Schawaller, 1982). All of these localities are much spider specimens were known from Messel although, sadly, younger than Messel. few are well preserved. She figured the araneid mentioned by Wunderlich (1986) and a nicely preserved hersiliid (Wedmann, 2018: figs 7.8–7.9, respectively). Wedmann Material and methods (2018) mentioned six opilionids yet to be described, and figured one (Wedmann, 2018: fig. -

August 2008 Issue 96

NEWSLETTER No. 96 THE FROG AND TADPOLE STUDY GROUP OF NSW INC The Year of the Frog Email [email protected] August 2008 PO Box 296 Rockdale NSW 2216 Website www.fats.org.au ABN 34 282 154 794 Pseudophryne covacevichae photo by Wendy Grimm Arrive at 6.30pm for a 7.00 pm start. AGM commences 7pm followed by our usual meeting Friday 1st August 2008 end of Jamieson St. (off Holker Street), Follow the signs to Building 22 Homebush Bay, Sydney Olympic Park Accessible by bus or train. Call us for details. Photo taken near Millaa Millaa on the Atherton tablelands The FATS Annual General Meeting commences on Friday at 7pm 1/8/08, for about 30 minutes and followed by our usual meeting. CONTENTS Main speakers 3 large glass tanks for sale, make us an offer, see p12 Mark Semeniuk p2-3 and Arthur White st MEETING FORMAT for 1 August 2008 Map of Arthur’s trip p4 Media clippings p4 6.30 pm Lots of White Lips, Gracilentas, Perons, Green Tree Frogs, Fallaxes and Rubellas need homes. Please bring your FATS Pharyngula p5 membership card, donation & amphibian licence to the meeting Bacteria could stop frog killer p6-7 and take home a lost froggy friend. Hiccups 7.00 pm Welcome and AGM have a purpose for tadpoles p8 7.30 pm Announcements. Cane toads on Oz p9 7.45 pm The main speaker is David Nelson :- “Bufo for breakfast. Greenwash, How Cane Toads affect native predators and their prey” bottled water and Coca Cola p10 9.00 pm Field trip reports and five favourite slides. -

Constraints on the Timescale of Animal Evolutionary History

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Constraints on the timescale of animal evolutionary history Michael J. Benton, Philip C.J. Donoghue, Robert J. Asher, Matt Friedman, Thomas J. Near, and Jakob Vinther ABSTRACT Dating the tree of life is a core endeavor in evolutionary biology. Rates of evolution are fundamental to nearly every evolutionary model and process. Rates need dates. There is much debate on the most appropriate and reasonable ways in which to date the tree of life, and recent work has highlighted some confusions and complexities that can be avoided. Whether phylogenetic trees are dated after they have been estab- lished, or as part of the process of tree finding, practitioners need to know which cali- brations to use. We emphasize the importance of identifying crown (not stem) fossils, levels of confidence in their attribution to the crown, current chronostratigraphic preci- sion, the primacy of the host geological formation and asymmetric confidence intervals. Here we present calibrations for 88 key nodes across the phylogeny of animals, rang- ing from the root of Metazoa to the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens. Close attention to detail is constantly required: for example, the classic bird-mammal date (base of crown Amniota) has often been given as 310-315 Ma; the 2014 international time scale indicates a minimum age of 318 Ma. Michael J. Benton. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Philip C.J. Donoghue. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Robert J. -

Early Tetrapod Relationships Revisited

Biol. Rev. (2003), 78, pp. 251–345. f Cambridge Philosophical Society 251 DOI: 10.1017/S1464793102006103 Printed in the United Kingdom Early tetrapod relationships revisited MARCELLO RUTA1*, MICHAEL I. COATES1 and DONALD L. J. QUICKE2 1 The Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, The University of Chicago, 1027 East 57th Street, Chicago, IL 60637-1508, USA ([email protected]; [email protected]) 2 Department of Biology, Imperial College at Silwood Park, Ascot, Berkshire SL57PY, UK and Department of Entomology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW75BD, UK ([email protected]) (Received 29 November 2001; revised 28 August 2002; accepted 2 September 2002) ABSTRACT In an attempt to investigate differences between the most widely discussed hypotheses of early tetrapod relation- ships, we assembled a new data matrix including 90 taxa coded for 319 cranial and postcranial characters. We have incorporated, where possible, original observations of numerous taxa spread throughout the major tetrapod clades. A stem-based (total-group) definition of Tetrapoda is preferred over apomorphy- and node-based (crown-group) definitions. This definition is operational, since it is based on a formal character analysis. A PAUP* search using a recently implemented version of the parsimony ratchet method yields 64 shortest trees. Differ- ences between these trees concern: (1) the internal relationships of aı¨stopods, the three selected species of which form a trichotomy; (2) the internal relationships of embolomeres, with Archeria -

Exceptional Fossil Preservation During CO2 Greenhouse Crises? Gregory J

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 307 (2011) 59–74 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Exceptional fossil preservation during CO2 greenhouse crises? Gregory J. Retallack Department of Geological Sciences, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403, USA article info abstract Article history: Exceptional fossil preservation may require not only exceptional places, but exceptional times, as demonstrated Received 27 October 2010 here by two distinct types of analysis. First, irregular stratigraphic spacing of horizons yielding articulated Triassic Received in revised form 19 April 2011 fishes and Cambrian trilobites is highly correlated in sequences in different parts of the world, as if there were Accepted 21 April 2011 short temporal intervals of exceptional preservation globally. Second, compilations of ages of well-dated fossil Available online 30 April 2011 localities show spikes of abundance which coincide with stage boundaries, mass extinctions, oceanic anoxic events, carbon isotope anomalies, spikes of high atmospheric carbon dioxide, and transient warm-wet Keywords: Lagerstatten paleoclimates. Exceptional fossil preservation may have been promoted during unusual times, comparable with fi Fossil preservation the present: CO2 greenhouse crises of expanding marine dead zones, oceanic acidi cation, coral bleaching, Trilobite wetland eutrophication, sea level rise, ice-cap melting, and biotic invasions. Fish © 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Carbon dioxide Greenhouse 1. Introduction Zeigler, 1992), sperm (Nishida et al., 2003), nuclei (Gould, 1971)and starch granules (Baxter, 1964). Taphonomic studies of such fossils have Commercial fossil collectors continue to produce beautifully pre- emphasized special places where fossils are exceptionally preserved pared, fully articulated, complex fossils of scientific(Simmons et al., (Martin, 1999; Bottjer et al., 2002). -

Toadally Frogs Frog Wranglers

Toadally Frogs Frog Wranglers P rogram Theme: • Frogs are toadally awesome! P rogram Messages: • Frogs are remarkable creatures • A frogs ability to adapt to its environment is evident in it physiology • Frogs are extremely sensitive to their surroundings and as a result are considered to be an indicator species P rogram Objectives: • Gallery Participants will observe live frogs face-to-face • Gallery Participants will be able to describe several physical features and unique qualities of the White’s tree frog • Gallery Participants will get excited about frogs Frog Wrangling Procedure 1. Wash and dry your hands. You may use regular tap water and light soap, but insure that you rinse your hands thoroughly. 2. Move frog from the Public Programs suite into carrying case. Whenever you transport your frog from the Public Programs suite to the exhibit, please carefully remove them from the habitat terrarium and place them in the small red carrying case (cooler). This will prevent the animal from becoming stressed as it is moved through the Museum. 3. Prepare your audience. Prior to bring out the live frog, ensure that everyone is seated and that you have asked your audience not to move quickly. Sit on the floor as well; this will ensure that if the frog leaps from your hands, it would not have far to fall. 4. Wet your hands. When you are ready to show the frog as part of your demonstration, please moisten your hands with the spray bottle. This will help minimize your dry skin from sucking the moisture out of the frog. -

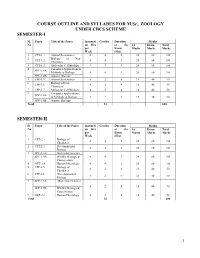

COURSE OUTLINE and SYLLABUS for M.Sc., ZOOLOGY UNDER CBCS SCHEME SEMESTER-I

COURSE OUTLINE AND SYLLABUS FOR M.Sc., ZOOLOGY UNDER CBCS SCHEME SEMESTER-I Sl. Paper Title of the Paper Instructi Credits Duration Marks No on Hrs of the IA Exam Total per Exam Marks Marks Marks Week (Hrs) 1 CPT-1.1 Animal Systematics 4 4 3 20 80 100 2 Biology of Non- CPT-1.2 4 4 3 20 80 100 Chordates 3 CPT-1.3 Molecular Cell Biology 4 4 3 20 80 100 4 Computer Applications & SPT-1.4A Methods in Biology 4 4 3 20 80 100 SPT-1.4B Aquatic Biology 5 CPP-1.5 Animal Systematics 4 2 4 10 40 50 6 Biology of Non- CPP-1.6 4 2 4 10 40 50 Chordates 7 CPP-1.7 Molecular Cell Biology 4 2 4 10 40 50 8 Computer Applications SPP-1.8A & Methods in Biology 4 2 4 10 40 50 SPP-1.8B Aquatic Biology Total 24 600 SEMESTER-II Sl. Paper Title of the Paper Instructi Credits Duration Marks No on Hrs of the IA Exam Total per Exam Marks Marks Marks Week (Hrs) 1 CPT-2.1 Biology of 4 4 3 20 80 100 Chordates 2 CPT-2.2 Developmental 4 4 3 20 80 100 Biology 3 SPT-2.3A Molecular Genetics SPT-2.3B Wildlife Biology & 4 4 3 20 80 100 Conservation 4 OET-2.4 Human Physiology 4 4 3 20 80 100 5 CPP-2.5 Biology of 4 2 4 10 40 50 Chordates 6 CPP-2.6 Developmental 4 2 4 10 40 50 Biology 7 SPP-2.7A Molecular Genetics 4 2 4 10 40 50 SPP-2.7B Wildlife Biology & Conservation 8 OEP-2.8 Human Physiology 4 2 4 10 40 50 Total 24 600 1 SEMESTER-III Sl. -

ROCEK, Z. and WUTTKE, M. (2010) Amphibia of Enspel (Late

Palaeobio Palaeoenv (2010) 90:321–340 DOI 10.1007/s12549-010-0042-0 ORIGINAL PAPER Amphibia of Enspel (Late Oligocene, Germany) ZbyněkRoček & Michael Wuttke Received: 23 April 2010 /Revised: 9 July 2010 /Accepted: 12 August 2010 /Published online: 29 September 2010 # Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung and Springer 2010 Abstract Amphibia from the Late Oligocene (MP 28) One specimen is a large premetamorphic tadpole (no locality Enspel, Germany are represented by two caudates: rudimentary limbs) with a total body length of 147 mm. a hyperossified salamandrid Chelotriton paradoxus and an Anatomically, it can be equally assigned to Pelobates or to indeterminate salamandrid different from Chelotriton in Eopelobates; the second possibility was excluded only on proportions of vertebral column. Anurans are represented the basis of absence of adult Eopelobates in this locality. by two forms of the genus Palaeobatrachus, one of which is nearly as large as P. gigas (now synonymized with P. Keywords Enspel . Oligocene . Salamandridae . grandipes). Pelobates cf. decheni, represented in this Chelotriton . Anura . Palaeobatrachus . Pelobates . Rana locality by three nearly complete adult skeletons and a large number of tadpoles, is the earliest record for the Abbreviation genus. Compared with later representatives of the genus, it DP FNSP Department of Palaeontology Faculty of does not yet possess specializations for burrowing. Ranidae Natural Sciences, Prague are represented by two rather fragmentary and incomplete skeletons referred to as Rana sp. A comparatively large series of tadpoles was assigned to the Pelobatidae on the basis of tripartite frontoparietal complex. Most of them are Introduction premetamorphic larvae, and a few older ones are post- metamorphic, but they do not exceed Gossner stage 42. -

Micro CT Scanning of a New Specimen of the Zygodactylidae (Aves) from the Early Eocene of Messel, Germany

Master Thesis, Department of Geosciences Micro CT scanning of a new specimen of the Zygodactylidae (Aves) from the Early Eocene of Messel, Germany Christian Haugen Svendsen Micro CT scanning of a new specimen of the Zygodactylidae (Aves) from the early Eocene of Messel, Germany Christian Haugen Svendsen Master Thesis in Geosciences Discipline: Palaeontology Department of Geosciences and Natural History museum, Oslo Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences University of Oslo September 2015 © Christian Haugen Svendsen, 2015 This work is published digitally through DUO – Digitale Utgivelser ved UiO http://www.duo.uio.no It is also catalogued in BIBSYS (http://www.bibsys.no/english) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. Acknowledgement I want to thank and dedicate this work to my aunt Rita. Thanks for taking me to the Natural History Museum in Oslo when I was just a small kid. You helped me to get a general interest in the Evolution of life, and how complex we are, and this gave a 7 year old boy a dream. A dream to become a Palaeontologist! First and foremost I would like to thank my two excellent supervisors, Jørn Hurum and Gerald Mayr. Thanks for helping me whenever I had questions and for your suggestions on the thesis. Your patience, readiness and excellent guidance were crucial for this thesis. Special thanks to Gerald for meeting me in Frankfurt on my trip there, and showing me the collection at the Senckenberg museum. I want to thank the Senckenberg museum in Frankfurt for letting me examine the bird fossils from their records for my thesis.