Stoutwear and the Discourses of Disorder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Do We Really Suffer for Fashion

University of Huddersfield Repository Almond, Kevin You have to suffer for Fashion Original Citation Almond, Kevin (2009) You have to suffer for Fashion. In: Public Lecture University Centre Barnsley, July 2009, University Centre Barnsley. (Unpublished) This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/9663/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ You have to suffer for Fashion Introduction: ‘You have to suffer fashion,’ has been a much used phrase throughout the history of fashion. Degrees of suffering and discomfort have varied and we have probably all endured agonies, in some way, when constructing our appearance, in order to face the world. This could range from a simple cut from shaving, to the discomfort and pain of folding tender flesh into a girdle! These are only two, of numerous possible examples. -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas R. Bell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Dr. Sabine Wilke, Chair Dr. Richard Block Dr. Eric Ames Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Germanics ©Copyright 2015 Thomas R. Bell University of Washington Abstract The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas Richard Bell Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Sabine Wilke Germanics This dissertation focuses on texts written by four contemporary, German-speaking authors: W. G. Sebald’s Die Ringe des Saturn and Schwindel. Gefühle, Daniel Kehlmann’s Die Vermessung der Welt, Sybille Lewitscharoff’s Blumenberg, and Peter Handke’s Der Große Fall. The project explores how the texts represent forms of religion in an increasingly secular society. Religious themes, while never disappearing, have recently been reactivated in the context of the secular age. This current societal milieu of secularism, as delineated by Charles Taylor, provides the framework in which these fictional texts, when manifesting religious intuitions, offer a postsecular perspective that serves as an alternative mode of thought. The project asks how contemporary literature, as it participates in the construction of secular dialogue, generates moments of religiously coded transcendence. What textual and narrative techniques serve to convey new ways of perceiving and experiencing transcendence within the immanence felt and emphasized in the modern moment? While observing what the textual strategies do to evoke religious presence, the dissertation also looks at the type of religious discourse produced within the texts. The project begins with the assertion that a historically antecedent model of religion – namely, Friedrich Schleiermacher’s – which is never mentioned explicitly but implicitly present throughout, informs the style of religious discourse. -

Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: an Investigation of Anti- Woman Perspectives Among Leathermen

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 5-2020 Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: An Investigation of Anti- Woman Perspectives among Leathermen Meredith G. F. Worthen University of Oklahoma, [email protected] Trenton M. Haltom University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Worthen, Meredith G. F. and Haltom, Trenton M., "Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: An Investigation of Anti-Woman Perspectives among Leathermen" (2020). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 707. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/707 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. digitalcommons.unl.edu Fifty Shades of Leather and Misogyny: An Investigation of Anti-Woman Perspectives among Leathermen Meredith G. F. Worthen1 and Trenton M. Haltom2 1 University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA; 2 University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, USA Corresponding author — Meredith G. F. Worthen, University of Oklahoma, 780 Van Vleet Oval, KH 331, Norman, OK 73019; [email protected] ORCID Meredith G. F. Worthen http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6765-5149 Trenton M. Haltom http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1116-4644 Abstract The Fifty Shades books and films shed light on a sexual and leather-clad subculture predominantly kept in the dark: bondage, discipline, submission, and sadomasoch- ism (BDSM). -

Ethical Fashion in the Age of Fast Fashion Sophie Xue Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Art Honors Papers Art Department 2018 Ethical Fashion in the Age of Fast Fashion Sophie Xue Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/arthp Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Fashion Design Commons Recommended Citation Xue, Sophie, "Ethical Fashion in the Age of Fast Fashion" (2018). Art Honors Papers. 26. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/arthp/26 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Art Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Ethical Fashion in the Age of Fast Fashion Sophie Xue Connecticut College Art Honor Thesis, 2017-2018 3 Acknowledgements Thank you Professor Pamela Marks for generously supporting and encouraging me to pursue this topic. I wouldn’t have come this far without your guidance. Thank you Professor Sabrina Notarfrancisco for introducing me to the world of fashion and teaching me how to sew. Thank you Professor Assor, Professor Bailey, Professor Barnard, Professor McDowell, Professor Gilbert, Professor Hendrickson, Professor Pelletier, Professor Shockey, Professor Wollensak for never failing to provide answers to my queries that fell within your broad areas of expertise. Thank you mom and dad for granting me the freedom to chase my wildest dreams and giving me a Connecticut College education. And finally thank you my friends, especially Nicolae Dorlea, you have inspired me and helped me tremendously along this journey. -

OPERATION HOUDINI (IRE) (5 Wins, £113,163 Viz

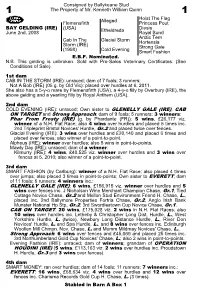

Consigned by Ballykeane Stud 1 The Property of Mr. Kenneth William Quinn 1 Hoist The Flag Alleged Flemensfirth Princess Pout BAY GELDING (IRE) (USA) Diesis June 2nd, 2008 Etheldreda Royal Bund Arctic Tern Cab In The Glacial Storm Hortensia Storm (IRE) Strong Gale (1998) Cold Evening Smart Fashion E.B.F. Nominated. N.B. This gelding is unbroken. Sold with Pre-Sales Veterinary Certificates. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CAB IN THE STORM (IRE): unraced; dam of 7 foals; 3 runners: Not A Bob (IRE) (05 g. by Old Vic): placed over hurdles at 6, 2011. She also has a 5-y-o mare by Flemensfirth (USA), a 4-y-o filly by Overbury (IRE), the above gelding and a yearling filly by Royal Anthem (USA). 2nd dam COLD EVENING (IRE): unraced; Own sister to GLENELLY GALE (IRE), CAB ON TARGET and Strong Approach; dam of 9 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners: Phar From Frosty (IRE) (g. by Phardante (FR)): 5 wins, £26,177 viz. winner of a N.H. Flat Race; also 4 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Tripleprint Bristol Novices' Hurdle, Gr.2 and placed twice over fences. Glacial Evening (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles and £20,140 and placed 6 times and placed over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Alpheus (IRE): winner over hurdles; also 5 wins in point-to-points. Mawly Day (IRE): unraced; dam of a winner: Kilmurry (IRE): 4 wins, £40,525 viz. winner over hurdles and 3 wins over fences at 5, 2010; also winner of a point-to-point. -

Consumption Patterns and Outward Expression of Quakers As Seen Through Historical Documentation and 18Th Century York County, Virginia Probate Inventories

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2002 For Profit and unction:F Consumption Patterns and Outward Expression of Quakers as Seen through Historical Documentation and 18th Century York County, Virginia Probate Inventories Darby O'Donnell College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation O'Donnell, Darby, "For Profit and unction:F Consumption Patterns and Outward Expression of Quakers as Seen through Historical Documentation and 18th Century York County, Virginia Probate Inventories" (2002). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626355. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-mznr-rn68 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOR PROFIT AND FUNCTION: CONSUMPTION PATTERNS AND OUTWARD EXPRESSION OF QUAKERS AS SEEN THROUGH HISTORICAL DOCUMENTATION AND 18 th CENTURY YORK COUNTY, VIRGINIA PROBATE INVENTORIES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Darby O’Donnell 2002 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Darby Q Donnell Approved, March 2002 Norman F. -

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles

The Shape of Women: Corsets, Crinolines & Bustles – c. 1790-1900 1790-1809 – Neoclassicism In the late 18th century, the latest fashions were influenced by the Rococo and Neo-classical tastes of the French royal courts. Elaborate striped silk gowns gave way to plain white ones made from printed cotton, calico or muslin. The dresses were typically high-waisted (empire line) narrow tubular shifts, unboned and unfitted, but their minimalist style and tight silhouette would have made them extremely unforgiving! Underneath these dresses, the wearer would have worn a cotton shift, under-slip and half-stays (similar to a corset) stiffened with strips of whalebone to support the bust, but it would have been impossible for them to have worn the multiple layers of foundation garments that they had done previously. (Left) Fashion plate showing the neoclassical style of dresses popular in the late 18th century (Right) a similar style ball- gown in the museum’s collections, reputedly worn at the Duchess of Richmond’s ball (1815) There was public outcry about these “naked fashions,” but by modern standards, the quantity of underclothes worn was far from alarming. What was so shocking to the Regency sense of prudery was the novelty of a dress made of such transparent material as to allow a “liberal revelation of the human shape” compared to what had gone before, when the aim had been to conceal the figure. Women adopted split-leg drawers, which had previously been the preserve of men, and subsequently pantalettes (pantaloons), where the lower section of the leg was intended to be seen, which was deemed even more shocking! On a practical note, wearing a short sleeved thin muslin shift dress in the cold British climate would have been far from ideal, which gave way to a growing trend for wearing stoles, capes and pelisses to provide additional warmth. -

Basinskimyersvap B Urns V Ogel S Ieczkowski K a M I N S K I Haukejorgenson B Aus B Rox L Owinger I Ijima D Enrow Taylorsmithtynes S Ikkema Dusie

BASINSKIMYERSVAP B URNS V OGEL S IECZKOWSKI K A M I N S K I HAUKEJORGENSON B AUS B ROX L OWINGER I IJIMA D ENROW TAYLORSMITHTYNES S IKKEMA DUSIE Cover art by Michael Basinski, 2012 ISSUE 13, VOL 4 NO 1 ISSN 1661-6685 For more information about DUSIE PRESS BOOKS and DUSIE the online literary journal, please visit: www.dusie.org/, or contact the editor at [email protected]. DUSIE ZÜRICH 2012 CONTRIBUTORS 6 Introduction 9 Michael Basinski 13 Danielle Vogel 17 Megan Burns 20 Sarah Vap 23 Gina Myers 29 Brenda Sieczkowski 34 Megan Kaminski 38 Nathan Hauke 44 Kirsten Jorgenson 48 Eric Baus 50 Robin Brox 55 Aaron Lowinger 61 Brenda Iijima 64 Jennifer Denrow 69 Shelly Taylor 74 Abraham Smith 79 Jen Tynes 87 Michael Sikkema 93 Contributor Bios 96 DUSIE NEWS In a selection from Lew Welch's Collected Poems, we get a crystal clear look at Radical Vernacular Poetics. I don't have the tech savvy to drum up the lovely zen calligraphy circle that heads the page but the text reads: Step out onto the Planet. Draw a circle a hundred feet round. Inside the circle are 300 things nobody understands, and maybe nobody's ever really seen. How many can you find? Between them, the poets in this issue found all 300 and then some. They found their 300 things on the bus, in hypnosis, on a social work call, listening to Elizabeth Cotton, thinking about Nicki Minaj, contemplating the edges of the mother body, finding ways to let the swamp gas speak, talking straight to the elephants in the room. -

Christian Temperance and Bible Hygiene

Christian Temperance and Bible Hygiene Ellen G. White 1890 Copyright © 2018 Ellen G. White Estate, Inc. Information about this Book Overview This eBook is provided by the Ellen G. White Estate. It is included in the larger free Online Books collection on the Ellen G. White Estate Web site. About the Author Ellen G. White (1827-1915) is considered the most widely translated American author, her works having been published in more than 160 languages. She wrote more than 100,000 pages on a wide variety of spiritual and practical topics. Guided by the Holy Spirit, she exalted Jesus and pointed to the Scriptures as the basis of one’s faith. Further Links A Brief Biography of Ellen G. White About the Ellen G. White Estate End User License Agreement The viewing, printing or downloading of this book grants you only a limited, nonexclusive and nontransferable license for use solely by you for your own personal use. This license does not permit republication, distribution, assignment, sublicense, sale, preparation of derivative works, or other use. Any unauthorized use of this book terminates the license granted hereby. (See EGW Writings End User License Agreement.) Further Information For more information about the author, publishers, or how you can support this service, please contact the Ellen G. White Estate i at [email protected]. We are thankful for your interest and feedback and wish you God’s blessing as you read. ii iii Preface Nearly thirty years ago there appeared in print the first of a series of remarkable and important articles on the subject of health, by Mrs. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

E-Print © BERG PUBLISHERS

Fashion Theory, Volume 14, Issue 1, pp. 83–104 DOI: 10.2752/175174110X12544983515196 Reprints available directly from the Publishers. Photocopying permitted by licence only. © 2010 Berg. Fashion Victims: On the Individualizing and De-individualizingE-Print Powers of Bjørn Schiermer Fashion Bjørn Schiermer holds a PhD Abstract scholarship at the Department of Sociology, University of Copenhagen. He is working This article discusses the popular notion of the “fashion victim.” It con- with fashion in a Simmelian and ceives of the notion of fashion victimization as an integral part of exis- phenomenological perspective. tence in modern individualized society. 1) Through analyzing different [email protected] accounts of fashion victimization, I aim to distil a common phenomeno- © BERGlogical core extant PUBLISHERS in these experiences. As we will see, these experiences tell us a great deal about the individualizing and de- individualizing dy- namics of fashion. 2) This analysis can be used, so I argue, to understand fashion as a sociocultural dynamic on its own terms. In so doing, I mean to isolate the most important elements of the experiences connected 84 Bjørn Schiermer to fashion dynamics, and thus create a phenomenological concept of fashion that captures all manifestations of fashion in society. 3) On the phenomenological level, the deciding factor is the object. It is through the experience of the fashionable object that the individualizing and de- individualizing powers of fashion are mediated. KEYWORDS: fashion, fashion victim, phenomenology of fashion, object of fashion Introduction The term “fashion victim” is a popular term nowadays. It is also a term that emphasizes the social hazards of fashion dynamics as these are per- ceived by the great majority in contemporary Western society.