(ED), Washington, DC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of the Lidice Memorial in Phillips, Wisconsin

“Our Heritage, Our Treasure”: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of the Lidice Memorial in Phillips, Wisconsin Emily J. Herkert History 489: Capstone November 2015 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by the McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire with the consent of the author. Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………...iii Lists of Figures and Maps………………………………………………………………………...iv Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..1 Background………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Historiography…………………………………………………………………………………….8 The Construction of the Lidice Memorial……………………………………………………….13 Memorial Rededication……………………………………………………………………….….20 The Czechoslovakian Community Festival……...………………………………………………23 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….28 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………………...30 ii Abstract The Lidice Memorial in Phillips, Wisconsin is a place of both memory and identity for the Czechoslovak community. Built in 1944, the monument initially represented the memory of the victims of the Lidice Massacre in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia while simultaneously symbolizing the patriotic efforts of the Phillips community during World War II. After the memorial’s rededication in 1984 the meaning of the monument to the community shifted. While still commemorating Lidice, the annual commemorations gave rise to the Phillips Czechoslovakian Community Festival held each year. The memorial became a site of cultural identity for the Phillips community and is -

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

Stirring the American Melting Pot: Middle Eastern Immigration, the Progressives, and the Legal Construction of Whiteness, 1880-1

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Stirring the American Melting Pot: Middle Eastern Immigration, the Progressives and the Legal Construction of Whiteness, 1880-1924 Richard Soash Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES STIRRING THE AMERICAN MELTING POT: MIDDLE EASTERN IMMIGRATION, THE PROGRESSIVES AND THE LEGAL CONSTRUCTION OF WHITENESS, 1880-1924 By RICHARD SOASH A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2013 Richard Soash defended this thesis on March 7, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jennifer Koslow Professor Directing Thesis Suzanne Sinke Committee Member Peter Garretson Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my Grandparents: Evan & Verena Soash Richard & Patricia Fluck iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am extremely thankful for both the academic and financial support that Florida State University has provided for me in the past two years. I would also like to express my gratitude to the FSU History Department for giving me the opportunity to pursue my graduate education here. My academic advisor and committee members – Dr. Koslow, Dr. Sinke, and Dr. Garretson – have been wonderful teachers and mentors during my time in the Master’s Program; I greatly appreciate their patience, humor, and knowledge, both inside and outside of the classroom. -

Nicaraguans Support Government, Speaker Says Fee-Payment Date

the weekly news magazine of IUPUI L “ M 3 American people misinformed Nicaraguans support government, speaker says by Kim Lanier The Indiana Council of Chur before As a reault. the Contras Seminary at chat sponsored a senes of lectures have little internal The Zavala • last at IUPUI on Central American af Has the neither fairs Nov. 27 thorufh Disc 4 to of a majority of the aar the tttfedti information on this area of Nicaraguan people because It me world due to me increasing len- sectors of the population that arete According to Roger Zavala, rec ocrorvl neL - tain 1 -i tor of the Baptist Seminary in has been trying to No problem for eld reefaents Managua. Nicaragua, the ■how the urorid that the members of the conference decided Is freely to carry out the lecture tour in the to end the premure, but out Fee-payment date moved up United States because the feel that ssdt influences are preventing it. the North Zavala said The threat from the are given all the information Contras positioned along the on the on U.S policy toward the Con- The real threat comm from US trae. the U.S backed counter military tmd economic support of hi revolutionary government Since the countenevohitinnanm The 1979, he said, Nicaragua has feh (am. Zavala aiad. is that the US are increasiag pressure from Americans, and Zavala said in his country it is m l the Reagan administration took of not the American peo| fice that is op- separation of Church and 'l l is the whole series of it doee not know means separation of pressures which is making bfe dif what It Is doing If Nicaraguans pohtks This, he said. -

Leon Bridges Black Moth Super Rainbow Melvins

POST MALONE ELEANOR FRIEDBERGER LORD HURON MELVINS LEON BRIDGES BEERBONGS & BENTLEYS REBOUND VIDE NOIR PINKUS ABORTION TECHNICIAN GOOD THING REPUBLIC FRENCHKISS RECORDS REPUBLIC IPECAC RECORDINGS COLUMBIA The world changes so fast that I can barely remember In contrast to her lauded 2016 album New View, Vide Noir was written and recorded over a two Featuring both ongoing Melvins’ bass player Steven Good Thing is the highly-anticipated (to put it lightly) life pre-Malone… But here we are – in the Future!!! – and which she arranged and recorded with her touring years span at Lord Huron’s Los Angeles studio and McDonald (Redd Kross, OFF!) and Butthole Surfers’, follow-up to Grammy nominated R&B singer/composer Post Malone is one of world’s unlikeliest hit-makers. band, Rebound was recorded mostly by Friedberger informal clubhouse, Whispering Pines, and was and occasional Melvins’, bottom ender Jeff Pinkus on Leon Bridges’ breakout 2015 debut Coming Home. Beerbongs & Bentleys is not only the raggedy-ass with assistance from producer Clemens Knieper. The mixed by Dave Fridmann (The Flaming Lips/MGMT). bass, Pinkus Abortion Technician is another notable Good Thing Leon’s takes music in a more modern Texas rapper’s newest album, but “a whole project… resulting collection is an entirely new sound for Eleanor, Singer, songwriter and producer Ben Schneider found tweak in the prolific band’s incredible discography. direction while retaining his renowned style. “I loved also a lifestyle” which, according to a recent Rolling exchanging live instrumentation for programmed drums, inspiration wandering restlessly through his adopted “We’ve never had two bass players,” says guitarist / my experience with Coming Home,” says Bridges. -

Proclamation 5682—July 20, 1987 101 Stat. 2169

PROCLAMATION 5682—JULY 20, 1987 101 STAT. 2169 As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the first animated feature-length film, we can be grateful for the art of film animation, which brings to the screen such magic and lasting vitality. We can also be grateful for the con tribution that animation has made to producing so many family films during the last half-century—films embodying the fundamental values of good over evil, courage, and decency that Americans so cherish. Through animation, we have witnessed the wonders of nature, ancient fables, tales of American heroes, and stories of youthful adventure. In recent years, our love for tech nology and the future has been reflected in computer-generated graphic art and animation. The achievements in the motion picture art that have followed since the debut of the first feature-length animated film in 1937 have mirrored the ar tistic development of American culture and the advancement of our Na tion's innovation and technology. By recognizing this anniversary, we pay tribute to the triimiph of creative genius that has prospered in our free en terprise system as nowhere else in the world. We recognize that, where men and women are free to express their creative talents, there is no limit to their potential achievement. In recognition of the special place of animation in American film history, the Congress, by House Joint Resolution 122, has authorized and requested the President to issue a proclamation calling upon the people of the United States to celebrate the week beginning July 16, 1987, with appropriate ob servances of the 50th anniversary of the animated feature film. -

Chapter 14: the Young State

LoneThe Star State 1845–1876 Why It Matters As you study Unit 5, you will learn that the time from when Texas became a state until it left the Union and was later readmitted was an eventful period. Long-standing problems, such as the public debt and relations with Mexico, were settled. The tragedy of the Civil War and the events of Reconstruction shaped Texas politics for many years. Primary Sources Library See pages 692–693 for primary source readings to accompany Unit 5. Cowboy Dance by Jenne Magafan (1939) was commissioned for the Anson, Texas, post office to honor the day Texas was admitted to the Union as the twenty-eighth state. Today this study can be seen at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. 316 “I love Texas too well to bring strife and bloodshed upon her.” —Sam Houston, “Address to the People,” 1861 CHAPTER XX Chapter Title GEOGRAPHY&HISTORY KKINGING CCOTTONOTTON 1910 1880 Cotton Production 1880--1974 Bales of Cotton (Per County) Looking at the 1880 map, you can see 25,000 to more than 100,000 By 1910, cotton farming had spread that cotton farming only took place in into central and West Texas. Where East Texas during this time. Why do 1,000 to was production highest? you think this was so? 24,999 999 or less Cotton has been “king” throughout most of Texas 1800s, the cotton belt spread westward as new tech- history. Before the Civil War it was the mainstay of the nologies emerged. Better, stronger plows made it eas- economy. -

US Army Logistics During the US-Mexican War and the Postwar Period, 1846-1860

CATALYST FOR CHANGE IN THE BORDERLANDS: U.S. ARMY LOGISTICS DURING THE U.S.-MEXICAN WAR AND THE POSTWAR PERIOD, 1846-1860 Christopher N. Menking Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 201 9 APPROVED: Richard McCaslin, Major Professor Sandra Mendiola Garcia, Committee Member Andrew Torget, Committee Member Alexander Mendoza, Committee Member Robert Wooster, Outside Reader Jennifer Jensen Wallach, Chair of the Department of History Tamara L. Brown, Executive Dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Menking, Christopher N. Catalyst for Change in the Borderlands: U.S. Army Logistics during the U.S.-Mexican War and the Postwar Period, 1846-1860. Doctor of Philosophy (History), December 2019, 323 pp., 3 figures, 3 appendices, bibliography, 52 primary sources, 140 secondary sources. This dissertation seeks to answer two primary questions stemming from the war between the United States and Mexico: 1) What methods did the United States Army Quartermaster Department employ during the war to achieve their goals of supporting armies in the field? 2) In executing these methods, what lasting impact did the presence of the Quartermaster Department leave on the Lower Río Grande borderland, specifically South Texas during the interwar period from 1848-1860? In order to obtain a complete understanding of what the Department did during the war, a discussion of the creation, evolution, and methodology of the Quartermaster Department lays the foundation for effective analysis of the department’s wartime methods and post-war influence. It is equally essential to understand the history of South Texas prior to the Mexican War under the successive control of Spain, Mexico and the United States and how that shaped the wartime situation. -

LOTS of LAND PD Books PD Commons

PD Commons From the collection of the n ^z m PrelingerTi I a JjibraryJj San Francisco, California 2006 PD Books PD Commons LOTS OF LAND PD Books PD Commons Lotg or ^ 4 I / . FROM MATERIAL COMPILED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE COMMISSIONER OF THE GENERAL LAND OFFICE OF TEXAS BASCOM GILES WRITTEN BY CURTIS BISHOP DECORATIONS BY WARREN HUNTER The Steck Company Austin Copyright 1949 by THE STECK COMPANY, AUSTIN, TEXAS All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine or newspaper. PRINTED AND BOUND IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA PD Books PD Commons Contents \ I THE EXPLORER 1 II THE EMPRESARIO 23 Ml THE SETTLER 111 IV THE FOREIGNER 151 V THE COWBOY 201 VI THE SPECULATOR 245 . VII THE OILMAN 277 . BASCOM GILES PD Books PD Commons Pref<ace I'VE THOUGHT about this book a long time. The subject is one naturally very dear to me, for I have spent all of my adult life in the study of land history, in the interpretation of land laws, and in the direction of the state's land business. It has been a happy and interesting existence. Seldom a day has passed in these thirty years in which I have not experienced a new thrill as the files of the General Land Office revealed still another appealing incident out of the history of the Texas Public Domain. -

WXYC Brings You Gems from the Treasure of UNC's Southern

IN/AUDIBLE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR a publication of N/AUDIBLE is the irregular newsletter of WXYC – your favorite Chapel Hill radio WXYC 89.3 FM station that broadcasts 24 hours a day, seven days a week out of the Student Union on the UNC campus. The last time this publication came out in 2002, WXYC was CB 5210 Carolina Union Icelebrating its 25th year of existence as the student-run radio station at the University of Chapel Hill, NC 27599 North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This year we celebrate another big event – our tenth anni- USA versary as the first radio station in the world to simulcast our signal over the Internet. As we celebrate this exciting event and reflect on the ingenuity of a few gifted people who took (919) 962-7768 local radio to the next level and beyond Chapel Hill, we can wonder request line: (919) 962-8989 if the future of radio is no longer in the stereo of our living rooms but on the World Wide Web. http://www.wxyc.org As always, new technology brings change that is both exciting [email protected] and scary. Local radio stations and the dedicated DJs and staffs who operate them are an integral part of vibrant local music communities, like the one we are lucky to have here in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Staff NICOLE BOGAS area. With the proliferation of music services like XM satellite radio Editor-in-Chief and Live-365 Internet radio servers, it sometimes seems like the future EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Nicole Bogas of local radio is doomed. -

Two Louies September 2003

OREGON MUSIC photo Chauncene Page 2 - TWO LOUIES, September 2003 TWO LOUIES, September 2003 - Page 3 photo David Ackerman Beauty Stab upstairs at Eli’s. The band lasted about a year but earned drummer Courtney Taylor a reputation as a rocker on the rise. “He always said he was going to the top,” says former Beauty Stab manager Tony DeMicoli. Taylor also worked the door at Tony’s club the Key Largo. “Courtney says the wide variety of acts at the Key had a big infl uence on his musical tastes”. This month Courtney and the Dandy Warhols set out to conquer the world with their new Capitol album “Welcome To The Monkey House” (See Jonny Hollywood page 8.) the music business. part of MusicFest NW, an expert from the AFM I wondered if any of these bands would like to (American Federation of Musicians) will be sitting regain the song rights that they signed away. At fi rst on a panel at the Roseland Grill. The panel discus- glance, there seems to be no legal way to achieve sion is titled “Sign on the Dotted Line”. The date this. Certainly, there could be a public outcry and is September 6, 2003, from 12-4 PM. As one of an attempt to shine some light on these predatory six panelists, there should be much insight offered promoters. Strangely, however, no one that entered regarding protection of your music. Secondly, I AFM ON KUFO this contest seems to be outraged. They should be. would like to invite all musicians interested in Dear Editor, The music business offers enough challenges with- improving their working environment to join me I was stunned upon learning the details of the “It’s Your Fault Band Search” contest, sponsored “I was stunned upon learning the details of the ‘It’s by Infi nity Broadcasting’s KUFO. -

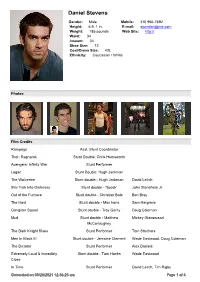

Daniel Stevens

Daniel Stevens Gender: Male Mobile: 310 956-7692 Height: 6 ft. 1 in. E-mail: [email protected] Weight: 185 pounds Web Site: http:// Waist: 34 Inseam: 34 Shoe Size: 12 Coat/Dress Size: 42L Ethnicity: Caucasian / White Photos Film Credits Rampage Asst. Stunt Coordinator Thor: Ragnarok Stunt Double: Chris Hemsworth Avengers: Infinity War Stunt Performer Logan Stunt Double: Hugh Jackman The Wolverine Stunt double - Hugh Jackman David Leitch Star Trek Into Darkness Stunt double - 'Spock' John Stoneham Jr. Out of the Furnace Stunt double - Christian Bale Ben Bray The Host Stunt double - Max Irons Sam Hargrave Gangster Squad Stunt double - Troy Garity Doug Coleman Mud Stunt double - Matthew Mickey Giacomazzi McConaughey The Dark Knight Rises Stunt Performer Tom Struthers Men In Black III Stunt double - Jemaine Clement Wade Eastwood, Doug Coleman The Dictator Stunt Performer Alex Daniels Extremely Loud & Incredibly Stunt double - Tom Hanks Wade Eastwood Close In Time Stunt Performer David Leitch, Tim Rigby Generated on 09/26/2021 12:36:25 am Page 1 of 3 Jack Gill, Daniel Stevens Green Lantern Stunt double - Ryan Reynolds Gary Powell Unstoppable Stunt double - Chris Pine Gary Powell Warrior Stunt Performer J.J. Perry The Expendables Stunt Performer Chad Stahelski X-Men Origins: Wolverine Stunt double - Hugh Jackman J.J. Perry, Chad Stahelski Takers Stunt Performer Lance Gilbert Angel of Death Stunt Performer Ron Yuan Once Fallen Stunt double - Peter Greene Noon Orsatti Iron Man Stunt double - 'Iron Man' Tom Harper, Keith Woulard Midnight Meat Train Stunt double - Vinnie Jones David Leitch Where The Wild Things Are Stunt double - 'Judith' Darrin Prescott Suffering Man's Charity Stunt double - Alan Cumming Nick Plantico Crank Stunt Performer Darrin Prescott Ravenswood Stunt double - Travis Fimmel Richard Boue Superman Returns Stunt Performer R.A.