How Japanese Comic Books Influence Taiwanese Students A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Glenn Gazette LERCIP High School

THE GLENN GAZETTE LERCIP HIGH SCHOOL Newsletter Staff Editor-in-Chief Idaliz Báez Layout Editors Adwoa Boakye, Elizabeth O’Malley, and Joshua Curry Production Editors Darla Kimbro, Maria Arredondo, and Stephanie Brown-Houston Staff Members Pooja Mude, Vinit Parikh, Poorva Limaye, Shreyasi Parihar, Lauren Wyman, and Breonna Slocum Volume 3, Number 1 Newsletter Staff.....................................................Page 3 Public Speaking or Business Etiquette: Cover Story There is so Much to Learn From Back to the Moon: NASA’s Vision for the Future and How goCarpeDiem...............................................Page 10 Glenn’s High School Interns are Contributing..........Page 5 How to behave and how to succeed goCarpeDiem, What does NASA have in store for this trip to our lunar a LERCIP and INSPIRE enrichment activity. neighbor? How have summer students helped influence the making of the Ares rockets? RePlay for Kids............................................Page 11 RePlay for Kids workshop summer interns attended. The Beginning of the Journey Interviews and More And They All Lived Happily Ever After: The Process of Attaining a NASA Internship...........Page 6 Preparing Gen Y for the Future.....................Page 12 Life isn’t always like a fairy tale, especially when it comes Dr. Woodrow Whitlow, Jr. to obtaining a NASA internship. Meeting the Man Behind the Curtain.............Page 12 Work Hard and Play Hard at NASA..........................Page 7 An interview with Mr. Hairston How the summer internship here at NASA is a more fulfilling experience than any other opportunity for high The Pioneering Spirit of Jo Ann Charleston..Page 14 school students. Ann Heyward: A Success Story.....................Page 15 Student Activities An interview with Mrs. -

Inuyasha Opening 4 Sheet Music

Inuyasha Opening 4 Sheet Music Download inuyasha opening 4 sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 1 pages partial preview of inuyasha opening 4 sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 1596 times and last read at 2021-09-26 14:54:54. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of inuyasha opening 4 you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Ensemble: Musical Ensemble Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Inuyasha Suite Inuyasha Suite sheet music has been read 3180 times. Inuyasha suite arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 22:20:36. [ Read More ] Inuyasha Ending 4 Inuyasha Ending 4 sheet music has been read 1343 times. Inuyasha ending 4 arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 1 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 22:48:04. [ Read More ] Inuyasha Inuyasha sheet music has been read 2333 times. Inuyasha arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 18:39:01. [ Read More ] Haikyuu Opening 4 Haikyuu Opening 4 sheet music has been read 2817 times. Haikyuu opening 4 arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 1 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 03:37:52. [ Read More ] Initial D Opening 1 Initial D Opening 1 sheet music has been read 1728 times. Initial d opening 1 arrangement is for Intermediate level. -

Chapter 11 Case No. 21-10632 (MBK)

Case 21-10632-MBK Doc 249 Filed 04/06/21 Entered 04/06/21 16:21:35 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 92 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY In re: Chapter 11 L’OCCITANE, INC., Case No. 21-10632 (MBK) Debtor. Judge: Hon. Michael B. Kaplan CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Ana M. Galvan, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned case. On April 2, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B: Notice of Deadline for Filing Proofs of Claim Against the Debtor L’Occitane, Inc. (attached hereto as Exhibit C) [Customized] Official Form 410 Proof of Claim (attached hereto as Exhibit D) Official Form 410 Instructions for Proof of Claim (attached hereto as Exhibit E) Dated: April 6, 2021 /s/ Ana M. Galvan Ana M. Galvan STRETTO 410 Exchange, Suite 100 Irvine, CA 92602 Telephone: 855-434-5886 Email: [email protected] Case 21-10632-MBK Doc 249 Filed 04/06/21 Entered 04/06/21 16:21:35 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 92 Exhibit A Case 21-10632-MBK Doc 249 Filed 04/06/21 Entered 04/06/21 16:21:35 Desc Main Document Page 3 of 92 Exhibit A Served via First-Class Mail Name Attention Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 City State Zip Country 1046 Madison Ave LLC c/o HMH Realty Co., Inc., Rexton Realty Co. -

Leon Bridges Black Moth Super Rainbow Melvins

POST MALONE ELEANOR FRIEDBERGER LORD HURON MELVINS LEON BRIDGES BEERBONGS & BENTLEYS REBOUND VIDE NOIR PINKUS ABORTION TECHNICIAN GOOD THING REPUBLIC FRENCHKISS RECORDS REPUBLIC IPECAC RECORDINGS COLUMBIA The world changes so fast that I can barely remember In contrast to her lauded 2016 album New View, Vide Noir was written and recorded over a two Featuring both ongoing Melvins’ bass player Steven Good Thing is the highly-anticipated (to put it lightly) life pre-Malone… But here we are – in the Future!!! – and which she arranged and recorded with her touring years span at Lord Huron’s Los Angeles studio and McDonald (Redd Kross, OFF!) and Butthole Surfers’, follow-up to Grammy nominated R&B singer/composer Post Malone is one of world’s unlikeliest hit-makers. band, Rebound was recorded mostly by Friedberger informal clubhouse, Whispering Pines, and was and occasional Melvins’, bottom ender Jeff Pinkus on Leon Bridges’ breakout 2015 debut Coming Home. Beerbongs & Bentleys is not only the raggedy-ass with assistance from producer Clemens Knieper. The mixed by Dave Fridmann (The Flaming Lips/MGMT). bass, Pinkus Abortion Technician is another notable Good Thing Leon’s takes music in a more modern Texas rapper’s newest album, but “a whole project… resulting collection is an entirely new sound for Eleanor, Singer, songwriter and producer Ben Schneider found tweak in the prolific band’s incredible discography. direction while retaining his renowned style. “I loved also a lifestyle” which, according to a recent Rolling exchanging live instrumentation for programmed drums, inspiration wandering restlessly through his adopted “We’ve never had two bass players,” says guitarist / my experience with Coming Home,” says Bridges. -

Referencia Bibliográfica: Saito, K. (2011). Desire in Subtext: Gender

Referencia bibliográfica: Saito, K. (2011). Desire in Subtext: Gender, Fandom, and Women’s Male-Male Homoerotic Parodies in Contemporary Japan. Mechademia, 6, 171–191. Disponible en https://muse.jhu.edu/article/454422 ISSN: - 'HVLUHLQ6XEWH[W*HQGHU)DQGRPDQG:RPHQ V0DOH0DOH +RPRHURWLF3DURGLHVLQ&RQWHPSRUDU\-DSDQ .XPLNR6DLWR Mechademia, Volume 6, 2011, pp. 171-191 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI0LQQHVRWD3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/mec.2011.0000 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mec/summary/v006/6.saito.html Access provided by University of Sydney Library (13 Nov 2015 18:03 GMT) KumiKo saito Desire in Subtext: Gender, Fandom, and Women’s Male–Male Homoerotic Parodies in Contemporary Japan Manga and anime fan cultures in postwar Japan have expanded rapidly in a manner similar to British and American science fiction fandoms that devel- oped through conventions. From the 1970s to the present, the Comic Market (hereafter Comiket) has been a leading venue for manga and anime fan activi- ties in Japan. Over the three days of the convention, more than thirty-seven thousand groups participate, and their dōjinshi (self-published fan fiction) and character goods generate ¥10 billion in sales.1 Contrary to the common stereo- type of anime/manga cult fans—the so-called otaku—who are males in their twenties and thirties, more than 70 percent of the participants in this fan fic- tion market are reported to be women in their twenties and thirties.2 Dōjinshi have created a locus where female fans vigorously explore identities and desires that are usually not expressed openly in public. The overwhelming majority of women’s fan fiction consists of stories that adapt characters from official me- dia to portray male–male homosexual romance and/or erotica. -

For My Short Witty Poems and for My Humorous Poems

Dear (I hope) Reader, A note from the poet: I'm probably best known (or unknown) for my short witty poems and for my humorous poems. None of the following poems are short, and most are not particularly witty or humorous, nor are they particularly rich in lyricism, image or "telling details" -- in fact, they are rather abstract, and have on occasion been praised or dismissed as "not poetry, but philosophical essays or sermons"; they are difficult, chunky with unpoeticized thought processes, perhaps arrogant and pontifical and preachy. Perhaps most are unpublishable (except here) -- though a few of them have been published. But they are the poems (of my own, that is) that please me most and seem to me, for all their faults, to do best what I want to do as a poet, something I have always felt needed doing and that few others seemed to be doing. These are the poems for which I'd most like to be remembered and the poems I feel others might find most valuable, though requiring a bit more work than my other poems. I won't try to explain what it is I want these poems to do, but hope that you'll read some of them and come to your own conclusions. Let me know what you think. Best, Dean Blehert [email protected] Lest We Forget Ronald Reagan is alive but forgetting things. An elephant never forgets, but this is personal, not political. We must make that distinction or all our politicians would be institutionalized for forgetting their promises. -

Victorian Poetry.Pdf

This Companion to Victorian Poetry provides an up-to-date introduction to many of the pressing issues that absorbed the attention of poets from the 1830s to the 1890s. It introduces readers to a range of topics - including historicism, patriotism, prosody, and religious belief. The thirteen specially- commissioned chapters offer fresh insights into the works of well-known figures such as Matthew Arnold, Robert Browning, and Alfred Tennyson and the writings of women poets - like Michael Field, Amy Levy, and Augusta Webster - whose contribution to Victorian culture has only recently been acknowledged by modern scholars. Revealing the breadth of the Victorians' experiments with poetic form, this Companion also discloses the extent to which their writings addressed the prominent intellectual and social questions of the day. The volume, which will be of interest to scholars and students alike, features a detailed chronology of the Victorian period and a compre- hensive guide to further reading. Cambridge Companions Online © Cambridge University Press, 2006 Cambridge Companions Online © Cambridge University Press, 2006 THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO VICTORIAN POETRY Cambridge Companions Online © Cambridge University Press, 2006 Cambridge Companions Online © Cambridge University Press, 2006 CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy The Cambridge Companion to Henry David edited by P. E. Easterling Thoreau The Cambridge Companion to Virgil edited by Joel Myerson edited by Charles Martindale The Cambridge Companion to Edith Wharton The Cambridge Companion to Old English edited by Millicent Bell Literature The Cambridge Companion to American edited by Malcolm Godden and Realism and Naturalism Michael Lapidge edited by Donald Pizer The Cambridge Companion to Dante The Cambridge Companion to Mark Twain edited by Rachel Jacoff edited by Forrest G. -

ENDER's GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third

ENDER'S GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third "I've watched through his eyes, I've listened through his ears, and tell you he's the one. Or at least as close as we're going to get." "That's what you said about the brother." "The brother tested out impossible. For other reasons. Nothing to do with his ability." "Same with the sister. And there are doubts about him. He's too malleable. Too willing to submerge himself in someone else's will." "Not if the other person is his enemy." "So what do we do? Surround him with enemies all the time?" "If we have to." "I thought you said you liked this kid." "If the buggers get him, they'll make me look like his favorite uncle." "All right. We're saving the world, after all. Take him." *** The monitor lady smiled very nicely and tousled his hair and said, "Andrew, I suppose by now you're just absolutely sick of having that horrid monitor. Well, I have good news for you. That monitor is going to come out today. We're going to just take it right out, and it won't hurt a bit." Ender nodded. It was a lie, of course, that it wouldn't hurt a bit. But since adults always said it when it was going to hurt, he could count on that statement as an accurate prediction of the future. Sometimes lies were more dependable than the truth. "So if you'll just come over here, Andrew, just sit right up here on the examining table. -

Friday, July 30, 2010 9:57:00 AM Update

July 30 - August 1, 2010 Baltimore Convention Center Baltimore, Maryland, USA Close This Window Back to main site SHOW ALL DAYS Friday, July 30, 2010 Saturday, July 31, 2010 Sunday, August 1, 2010 Filter by Track/Location: Show ALL Tracks/Locations | Clear All Filters Friday, July 30, 2010 9:57:00 AM 8:00 AM 9:00 AM 10:00 AM 11:00 AM 12:00 PM 1:00 PM 2:00 PM 3:00 PM 4:00 PM 5:00 PM 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 9:00 PM 10:00 PM 11:00 PM 12:00 AM 1:00 AM 2:00 AM Main Events Concert - Yoshid... Arena Masquerade Registration Video 1 Ah My Buddha La Corda D'Oro P... AMV Overflow Eureka 7: Good Night, Sleep Tigh... AMV Contest Skullman 1-6 Vampire Girl vs. Frankenstein Gi... Urotsukidoji: Legend of the Over... Video 2 Sands of Destruction Gakuen Alice Ikkitousen: Dragon Destiny 1-2 Bamboo Blade 1-4 [S] Utawarerumono 1-... Murder Princess 1-6 [S] Master of Martial Hearts 1-5 [18+] Junjo Romantica Season 1 DVD Col... Cleavage [18+] Video 3 Otaku no Video [S] Yawara! 15-21 [S] Galaxy Express 999 TV 5-8 Masked Rider: The First [S] Dairugger XV 1-6 [S] Cyborg 009: Monster Wars Dragon Ball 53-58 [S] Video 4 Afghan Star [L] Taxi Hunter [L] V3 Samseng Jalanan [L] Paku Kuntilanak... The Kid With the Golden... Power Kids [L] Seven Days [L] Hard Revenge Milly: Bloody Battle Ac... Art of the Devil 3 [L][1.. -

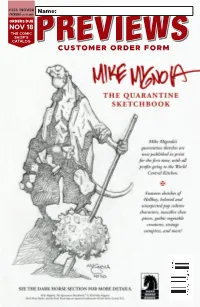

Customer Order Form

#386 | NOV20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Nov20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:23:12 AM Nov20 Ad DST Rogue.indd 1 10/8/2020 11:07:39 AM PREMIER COMICS HAHA #1 IMAGE COMICS 30 RAIN LIKE HAMMERS #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 CRIMSON FLOWER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 62 AVATAR: THE NEXT SHADOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 64 MARVEL ACTION: CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING 104 KING IN BLACK: BLACK KNIGHT #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-6 RED SONJA: THE SUPER POWERS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 126 ABBOTT: 1973 #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 158 Nov20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:24:32 AM COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE FEATURED ITEMS Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS I Breathed A Body #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS 1 Delicates TP l ONI PRESS l I Breathed A Body #1 AFTERSHOCK COMICS 1 The Cutting Edge: Devil’s Mirror #1 l TITAN COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS Knights of Heliopolis HC l TITAN COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Blade Runner 2029 #2 l TITAN COMICS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars Insider #200 l TITAN COMICS Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Comic Book Creator #25 l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Bloodshot #9 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Vagrant Queen Volume 2: A Planet Called Doom TP l VAULT COMICS Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. -

EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) Chart Ill 1111 Ill Changes #BXNCCVR 3 -DIGIT 908

$6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) Chart Ill 1111 Ill Changes #BXNCCVR 3 -DIGIT 908 II 1111[ III.IIIIIII111I111I11II11I11III I II...11 #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 897 A06 B0098 001 MAR 04 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A Overview LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 Page 10 New Features l3( AUGUST 2, 2003 Page 57 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT www.billboard.com HOT SPOTS New Player Eyes iTunes BuyMusic.com Rushes Dow nload Service to PC Market BY BRIAN GARRITY Audio -powered stores long offered by Best Buy, Tower Records and fye.com. NEW YORK -An unlikely player has hit the Web What's more, digital music executives say BuyMusic with the first attempt at a Windows -friendly answer highlights a lack of consistency on the part of the labels to Apple's iTunes Music Store: buy.com founder when it comes to wholesaling costs and, more importantly, Scott Blum. content urge rules. The entrepreneur's upstart pay -per-download venture,' In fact, this lack of consensus among labels is shap- buymusic.com, is positioning itself with the advertising ing up as a central challenge for all companies hoping slogan "Music downloads for the rest of us." to develop PC -based download stores. But beyond its iTunes- inspired, big -budget TV mar- "While buy.com's service is the least restrictive [down- the new service is less a Windows load store] that is currently available in the Windows keting campaign, SCOTT BLUI ART VENTURE 5 Trio For A Trio spin on Apple's offering and more like the Liquid (Continued on page 70) Multicultural trio Bacilos garners three nominations for fronts the Latin Grammy Awards. -

TESTAMENT Release Date Pre-Order Start the Formation of Damnation Uu 25/01/2019 Uu 07/12/2018

New Release Information uu January TESTAMENT Release Date Pre-Order Start The Formation Of Damnation uu 25/01/2019 uu 07/12/2018 uu advertising in many important music magazines DEC/JAN 2019 uu album reviews, interviews in all important Metal magazines in Europe’s DEC/JAN 2019 issues uu song placements in European magazine compilations uu spotify playlists in all European territories LP15 uu instore decoration: flyers NB 4747-1 LP+CD (black in gatefold) uu Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Google+ organic promotion uu Facebook ads and promoted posts + Google ads in both the search and display networks, bing ads and gmail ads uu Banner advertising on more than 60 most important Metal & Rock websites all over Europe uu additional booked ads on Metal Hammer Germany and UK, and in Territory: World the Fixion network (mainly Blabbermouth) uu video and pre-roll ads on You tube uu ad campaigns on iPhones for iTunes and Google Play for Androids uu banners, featured items at the shop, header images and a back- ground on nuclearblast.de and nuclearblast.com uu features and banners in newsletters, as well as special mailings to targeted audiences in support of the release TOUR: uu Tracklists: 21.06. B Dessel ...Graspop Metal Meeting 04.07. DK Roskilde ......... Roskilde Festival 07. - 10.08. CD: 01. For The Glory Of… 25.06. PL Krakow ..............Mystic Festival 05./07.07. CZ Jarom .................Brutal Assault 02. More Than Meets The Eye 27.06. I Bologna ....................Sonic Park E Barcelona ................... Rock Fest 08. - 10.08. 03. The Evil Has Landed 29.06.