Draba Weberi Price & Rollins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colorado Wildlife Action Plan: Proposed Rare Plant Addendum

Colorado Wildlife Action Plan: Proposed Rare Plant Addendum By Colorado Natural Heritage Program For The Colorado Rare Plant Conservation Initiative June 2011 Colorado Wildlife Action Plan: Proposed Rare Plant Addendum Colorado Rare Plant Conservation Initiative Members David Anderson, Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP) Rob Billerbeck, Colorado Natural Areas Program (CNAP) Leo P. Bruederle, University of Colorado Denver (UCD) Lynn Cleveland, Colorado Federation of Garden Clubs (CFGC) Carol Dawson, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Michelle DePrenger-Levin, Denver Botanic Gardens (DBG) Brian Elliott, Environmental Consulting Mo Ewing, Colorado Open Lands (COL) Tom Grant, Colorado State University (CSU) Jill Handwerk, Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP) Tim Hogan, University of Colorado Herbarium (COLO) Steve Kettler, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Andrew Kratz, U.S. Forest Service (USFS) Sarada Krishnan, Colorado Native Plant Society (CoNPS), Denver Botanic Gardens Brian Kurzel, Colorado Natural Areas Program Eric Lane, Colorado Department of Agriculture (CDA) Paige Lewis, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) Ellen Mayo, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Mitchell McGlaughlin, University of Northern Colorado (UNC) Jennifer Neale, Denver Botanic Gardens Betsy Neely, The Nature Conservancy Ann Oliver, The Nature Conservancy Steve Olson, U.S. Forest Service Susan Spackman Panjabi, Colorado Natural Heritage Program Jeff Peterson, Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) Josh Pollock, Center for Native Ecosystems (CNE) Nicola Ripley, -

Laurentian Mixed Forest Province, Cliff/Talus System Summary

CT Cliff and Talus System photo by M.D. Lee MN DNR Lake County, MN General Description Communities in the Cliff/Talus (CT) System are present on cliffs or talus slopes on steep- sided knobs, in river gorges, along lakeshores, and in other settings with sheer bedrock exposures. Often, cliffs and talus slopes are associated with one another because talus slopes are composed of rock fractured either from cliffs or from exposed bedrock on steep hillsides. The vegetation of CT communities is generally open. Lichens and moss- es are the dominant life forms, with vascular plants sparse or patchy because of scarcity of soil. In this classification, cliff communities are grouped by moisture and light regimes and by bedrock type, which are the major determinants of species composition. Cliff habitats range from warm and dry to cool and wet depending on cliff aspect, proximity to streams or lake shores, and presence of groundwater seepage on the cliff face. In the Laurentian Mixed Forest (LMF) Province, cliffs are formed most commonly of igneous bedrock, although cliffs on metamorphic rock are also common. Talus communities are classified according to amount of woody plant cover and moisture regime. In the LMF Province, CT communities are restricted mostly to the North Shore High- lands and Border Lakes subsections in NSU, where Precambrian bedrock is frequently at or just below the surface and topography is often rugged. Scattered cliffs are present in WSU and are likely in the Laurentian Uplands Subsection in NSU and the Littlefork- Vermilion Uplands Subsection in Northern Minnesota & Ontario Peatlands MOP, primar- ily along lakes and streams where water has exposed the underlying bedrock. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Atlas of Stem Anatomy in Herbs, Shrubs and Trees Volume 1

F.H. Schweingruber, A. Börner, E.-D. Schulze Atlas of Stem Anatomy in Herbs, Shrubs and Trees Volume 1 ▶ Presents a taxonomical and ecological evaluation of stem anatomical features of all life forms of dicotyledonous Angiosperms ▶ Contains more than 2000 color illustrations ▶ Has a high aesthetic value ▶ Opens vast fields of research for dendrochronology, wood anatomy, taxonomy and ecology This work, published in two volumes, contains descriptions of the wood and bark anatomies of 3000 dicotyledonous plants of 120 families, highlighting the anatomical and phylogenetic diversity of dicotyledonous plants of the Northern Hemisphere. The first volume principally treats families of the Early Angiosperms, Eudicots, Core Eudicots and Rosids, while the second concentrates on the Asterids. 2011, VIII, 495 p. Presented in Volume 1 are microsections of the xylem and phloem of herbs, shrubs and trees of 1200 species and 85 families of various life forms of the temperate zone along Printed book altitudinal gradients from the lowland at the Mediterranean coast to the alpine zone in Hardcover Western Europe. The global perspective of the findings is underlined by the analysis of ▶ 140,18 € | £129.99 | $199.99 500 species from the Caucasus, the Rocky Mountains and Andes, the subtropical zone on ▶ *149,99 € (D) | 154,20 € (A) | CHF 165.50 the Canary Islands, the arid zones in the Sahara, in Eurasia, Arabia and Southwest North America, and the boreal and arctic zones in Eurasia and Canada. eBook The presence of annual rings in all life forms demonstrates that herbs and dwarf shrubs Available from your bookstore or are an excellent tool for the reconstruction of annual biomass production and the ▶ springer.com/shop interannual dynamic of plant associations. -

A New Application for Phylogenetic Marker Development Using Angiosperm Transcriptomes Author(S): Srikar Chamala, Nicolás García, Grant T

MarkerMiner 1.0: A New Application for Phylogenetic Marker Development Using Angiosperm Transcriptomes Author(s): Srikar Chamala, Nicolás García, Grant T. Godden, Vivek Krishnakumar, Ingrid E. Jordon- Thaden, Riet De Smet, W. Brad Barbazuk, Douglas E. Soltis, and Pamela S. Soltis Source: Applications in Plant Sciences, 3(4) Published By: Botanical Society of America DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/apps.1400115 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3732/apps.1400115 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. ApApplicatitionsons Applications in Plant Sciences 2015 3 ( 4 ): 1400115 inin PlPlant ScienSciencesces S OFTWARE NOTE M ARKERMINER 1.0: A NEW APPLICATION FOR PHYLOGENETIC 1 MARKER DEVELOPMENT USING ANGIOSPERM TRANSCRIPTOMES S RIKAR C HAMALA 2,12 , N ICOLÁS G ARCÍA 2,3,4 * , GRANT T . G ODDEN 2,3,5 * , V IVEK K RISHNAKUMAR 6 , I NGRID E. -

Taxa Named in Honor of Ihsan A. Al-Shehbaz

TAXA NAMED IN HONOR OF IHSAN A. AL-SHEHBAZ 1. Tribe Shehbazieae D. A. German, Turczaninowia 17(4): 22. 2014. 2. Shehbazia D. A. German, Turczaninowia 17(4): 20. 2014. 3. Shehbazia tibetica (Maxim.) D. A. German, Turczaninowia 17(4): 20. 2014. 4. Astragalus shehbazii Zarre & Podlech, Feddes Repert. 116: 70. 2005. 5. Bornmuellerantha alshehbaziana Dönmez & Mutlu, Novon 20: 265. 2010. 6. Centaurea shahbazii Ranjbar & Negaresh, Edinb. J. Bot. 71: 1. 2014. 7. Draba alshehbazii Klimeš & D. A. German, Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 158: 750. 2008. 8. Ferula shehbaziana S. A. Ahmad, Harvard Pap. Bot. 18: 99. 2013. 9. Matthiola shehbazii Ranjbar & Karami, Nordic J. Bot. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-1051.2013.00326.x, 10. Plocama alshehbazii F. O. Khass., D. Khamr., U. Khuzh. & Achilova, Stapfia 101: 25. 2014. 11. Alshehbazia Salariato & Zuloaga, Kew Bulletin …….. 2015 12. Alshehbzia hauthalii (Gilg & Muschl.) Salariato & Zuloaga 13. Ihsanalshehbazia Tahir Ali & Thines, Taxon 65: 93. 2016. 14. Ihsanalshehbazia granatensis (Boiss. & Reuter) Tahir Ali & Thines, Taxon 65. 93. 2016. 15. Aubrieta alshehbazii Dönmez, Uǧurlu & M.A.Koch, Phytotaxa 299. 104. 2017. 16. Silene shehbazii S.A.Ahmad, Novon 25: 131. 2017. PUBLICATIONS OF IHSAN A. AL-SHEHBAZ 1973 1. Al-Shehbaz, I. A. 1973. The biosystematics of the genus Thelypodium (Cruciferae). Contrib. Gray Herb. 204: 3-148. 1977 2. Al-Shehbaz, I. A. 1977. Protogyny, Cruciferae. Syst. Bot. 2: 327-333. 3. A. R. Al-Mayah & I. A. Al-Shehbaz. 1977. Chromosome numbers for some Leguminosae from Iraq. Bot. Notiser 130: 437-440. 1978 4. Al-Shehbaz, I. A. 1978. Chromosome number reports, certain Cruciferae from Iraq. -

Field Release of the Gall Mite, Aceria Drabae

United States Department of Field release of the gall mite, Agriculture Aceria drabae (Acari: Marketing and Regulatory Eriophyidae), for classical Programs biological control of hoary Animal and Plant Health Inspection cress (Lepidium draba L., Service Lepidium chalapense L., and Lepidium appelianum Al- Shehbaz) (Brassicaceae), in the contiguous United States. Environmental Assessment, January 2018 Field release of the gall mite, Aceria drabae (Acari: Eriophyidae), for classical biological control of hoary cress (Lepidium draba L., Lepidium chalapense L., and Lepidium appelianum Al-Shehbaz) (Brassicaceae), in the contiguous United States. Environmental Assessment, January 2018 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. -

Draba Cana Rydb

Draba cana Rydb. synonym: Draba lanceolata Royle (misapplied), Draba breweri S. Watson var. cana (Rydb.) Rollins lance-leaved draba Brassicaceae - mustard family status: State Sensitive, BLM sensitive, USFS sensitive rank: G5 / S1S2 General Description: Perennial, ashy-colored, 5-25 cm tall, arising from a simple or branched woody base. Stems several, simple to freely branched, covered with simple to many-branched hairs. Leaves woolly, with soft, star-shaped or many-branched hairs. Basal leaves rosette-forming, oblanceolate, 1-3 cm long, entire to small-toothed, often with simple hairs along the leaf margins. Stem leaves several, narrowly to broadly lanceolate, generally toothed, and covered with mostly forked hairs. Floral Characteristics: Racemes with 10-50 flowers, elongate in fruit. Petals 4, white, 3-5 mm long, notched at the tip. Stamens 6. Fruits: Lanceolate to oblong silicle, 4-12 x 1.5-3 mm, soft-hairy with Illustration by Jeanne R. Janish, simple to branched hairs, and often somewhat contorted. Style 0.2-0.5 ©1964 University of Washington (0.8) mm long. Seeds 20-50, less than 1 mm long. Identifiable May to Press July; usually in full flower and fruit by late June. Identif ication Tips: This species keys to Draba lanceolata in Hitchcock & C ronquist (1973), though the name has been misapplied to WA plants. It is istinguished from other Draba species in its range by its leafy stems and white petals. D. cras s ifolia, D. incerta, D. oligos perma, D. pays onii, and D. ruaxes have yellow flowers and leafless stems (but D. crassifolia and D. -

Green Mountain Reservoir Substitution and Power Interference Agreements Final EA

Green Mountain Reservoir Substitution and Power Interference Agreements Final EA Table of Contents Acronyms...................................................................................................................................... vi 1.0 Purpose and Need .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Introduction.......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Project Purpose and Need .................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 Study Area........................................................................................................... 1-2 1.4 Background.......................................................................................................... 1-2 1.4.1 Prior Appropriation System .....................................................................1-2 1.4.2 Reclamation and Green Mountain Reservoir...........................................1-2 1.4.3 Western Area Power Administration.......................................................1-4 1.4.4 Springs Utilities’ Collection Systems and Customers .............................1-4 1.4.5 Blue River Decree....................................................................................1-7 1.4.6 Substitution Year Operations...................................................................1-8 1.4.7 Substitution Memorandums of Agreement............................................1-10 -

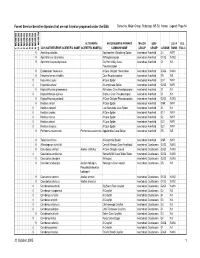

Sensitive Species That Are Not Listed Or Proposed Under the ESA Sorted By: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci

Forest Service Sensitive Species that are not listed or proposed under the ESA Sorted by: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci. Name; Legend: Page 94 REGION 10 REGION 1 REGION 2 REGION 3 REGION 4 REGION 5 REGION 6 REGION 8 REGION 9 ALTERNATE NATURESERVE PRIMARY MAJOR SUB- U.S. N U.S. 2005 NATURESERVE SCIENTIFIC NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME(S) COMMON NAME GROUP GROUP G RANK RANK ESA C 9 Anahita punctulata Southeastern Wandering Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G4 NNR 9 Apochthonius indianensis A Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1G2 N1N2 9 Apochthonius paucispinosus Dry Fork Valley Cave Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 Pseudoscorpion 9 Erebomaster flavescens A Cave Obligate Harvestman Invertebrate Arachnid G3G4 N3N4 9 Hesperochernes mirabilis Cave Psuedoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G5 N5 8 Hypochilus coylei A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G3? NNR 8 Hypochilus sheari A Lampshade Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 NNR 9 Kleptochthonius griseomanus An Indiana Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Kleptochthonius orpheus Orpheus Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 9 Kleptochthonius packardi A Cave Obligate Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 N2N3 9 Nesticus carteri A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid GNR NNR 8 Nesticus cooperi Lost Nantahala Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Nesticus crosbyi A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1? NNR 8 Nesticus mimus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2 NNR 8 Nesticus sheari A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR 8 Nesticus silvanus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR -

Ce Standards Outlined in FHWA’S Monitoring Plan and As Required by the USACE Section 404 Permit Conditions

Fremont Pass Rec Pathway Figure 1. Project Location and Vicinity 2 Fremont Pass Rec Pathway Purpose and Need The purpose of the proposed project is to improve the safety of cyclists traveling along State Highway (SH) 91 in Tenmile Canyon. Currently, cyclists travelling south from Copper Mountain toward Fremont Pass must ride on SH 91 through Tenmile Canyon. This situation presents safety concerns for cyclists and drivers through this approximately 3.3-mile segment of highway as it has limited shoulder widths, tight curves, high speeds, and short line of sight distances. In addition, there is a need to provide additional multi-use pathways in Summit County, Colorado. Not only does Summit County aim to accomplish its objectives to maintain, enhance, connect, and expand the recreation pathway system, the Tenmile Canyon corridor south of Copper Mountain has been identified as a high priority pathway in Governor Hickenlooper’s “Colorado the Beautiful: Colorado’s 16” trails initiative. The recreation pathway system in Summit County continues to experience increased demand and utilization. The proposed project would complement the current recreation pathway in Summit County by offering an extension of this system with the proposed pathway towards Fremont Pass. In addition to benefiting cyclists, the multi-modal pathway will allow walkers, runners, and other non-motorized recreational users to access this section of Tenmile Canyon. Description of the Proposed Action Construction of the new recreation pathway would be on National Forest system lands managed by the USFS. The proposed pathway alignment would use the existing, abandoned railroad grade in Tenmile Canyon. This alignment is on the east side of both Tenmile Creek and SH 91. -

Southern Rockies Lynx Linkage Areas

Southern Rockies Lynx Amendment Appendix D - Southern Rockies Lynx Linkage Areas The goal of linkage areas is to ensure population viability through population connectivity. Linkage areas are areas of movement opportunities. They exist on the landscape and can be maintained or lost by management activities or developments. They are not “corridors” which imply only travel routes, they are broad areas of habitat where animals can find food, shelter and security. The LCAS defines Linkage areas as: “Habitat that provides landscape connectivity between blocks of habitat. Linkage areas occur both within and between geographic areas, where blocks of lynx habitat are separated by intervening areas of non-habitat such as basins, valleys, agricultural lands, or where lynx habitat naturally narrows between blocks. Connectivity provided by linkage areas can be degraded or severed by human infrastructure such as high-use highways, subdivisions or other developments. (LCAS Revised definition, Oct. 2001). Alpine tundra, open valleys, shrubland communities and dry southern and western exposures naturally fragment lynx habitat within the subalpine and montane forests of the Southern Rocky Mountains. Because of the southerly latitude, spruce-fir, lodgepole pine, and mixed aspen-conifer forests constituting lynx habitat are typically found in elevational bands along the flanks of mountain ranges, or on the summits of broad, high plateaus. In those circumstances where large landforms are more isolated, they still typically occur within 40 km (24 miles) of other suitable habitat (Ruggerio et al. 2000). This distribution maintains the potential for lynx movement from one patch to another through non-forest environments. Because of the fragmented nature of the landscape, there are inherently important natural topographic features and vegetation communities that link these fragmented forested landscapes of primary habitat together, providing for dispersal movements and interchange among individuals and subpopulations of lynx occupying these forested landscapes.