Public Histories of Australian and British Women’S Suffrage: Some Comparative Issues1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(WA) from 1938 to 1980 and Its Role in the Cultural Life of Perth

The Fellowship of Australian Writers (WA) from 1938 to 1980 and its role in the cultural life of Perth. Patricia Kotai-Ewers Bachelor of Arts, Master of Philosophy (UWA) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Murdoch University November 2013 ABSTRACT The Fellowship of Australian Writers (WA) from 1938 to 1980 and its role in the cultural life of Perth. By the mid-1930s, a group of distinctly Western Australian writers was emerging, dedicated to their own writing careers and the promotion of Australian literature. In 1938, they founded the Western Australian Section of the Fellowship of Australian Writers. This first detailed study of the activities of the Fellowship in Western Australia explores its contribution to the development of Australian literature in this State between 1938 and 1980. In particular, this analysis identifies the degree to which the Fellowship supported and encouraged individual writers, promoted and celebrated Australian writers and their works, through publications, readings, talks and other activities, and assesses the success of its advocacy for writers’ professional interests. Information came from the organisation’s archives for this period; the personal papers, biographies, autobiographies and writings of writers involved; general histories of Australian literature and cultural life; and interviews with current members of the Fellowship in Western Australia. These sources showed the early writers utilising the networks they developed within a small, isolated society to build a creative community, which welcomed artists and musicians as well as writers. The Fellowship lobbied for a wide raft of conditions that concerned writers, including free children’s libraries, better rates of payment and the establishment of the Australian Society of Authors. -

The Muriel Matters Society Epistle

The Muriel Matters Proudly supported by: Society Epistle No: 16 (October 2012) Hello Members and Friends! Our next event will be to commemorate the 104th Anniversary of The Grille Protest on Sunday, 4 November, 2012 from 1.00pm to 3.00pm at MRC/Lions Community Centre, 23 Coglin Street, Adelaide 5000 (located between Gouger and Wright Streets, near Central Market). RSVP (helpful!) to 0437 656 700 or [email protected]. Mr Ron Potts, a highly regarded speaker, has kindly agreed to bring along his ‘magic lantern’ and address us on the history of the ‘kinematograph’ - the technology Muriel brought with her to Australia to ‘vividly illustrate with pictures’ her lectures during the 1910 Tour to Perth, Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney. Accompanied by her great friend, Violet Tillard, (who may have operated the lantern), the tour informed her eager audiences about her adventures in England, assisting British women to secure the franchise. The secrets of ‘magic lantern’ operation will be revealed!! An event – like the original – not to be missed! (Invitations have already been emailed to members who have supplied their email address. If you didn’t receive an email, and have access to email, please advise your email address asap. Newsletters can then also be emailed. Thanks!) Memberships Due: for those yet to renew, payments can be made at the meeting or by cheque or direct bank transfer via the form enclosed. Please remember - your subs keep Muriel projects happening – thank you! UK News The recent London Olympic Opening Ceremony did feature a vignette on suffrage. Women and girls, in Edwardian costume, carried a suffrage banner in the segment choreographed by Australian Danny Boyle, while the story of the struggle for Votes for Women was narrated by Sir Kenneth Branagh. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

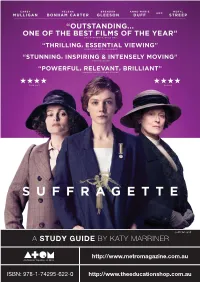

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

CEDAW Opening Statement 19.6.2018

CEDAW Opening Statement Madam Chair, distinguished members of the Committee. Before I begin I would like to acknowledge the traditional owners on whose land we meet today and pay my respects to elders past and present. It is a great pleasure to meet with you today, to engage in a constructive dialogue about Australia’s implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women. Being here, I am humbled by the great Australian women who have come before me, trailblazers like feminist and activist, Jessie Street. 90 years ago Jessie Street came to this very building to advocate for Australian women’s economic independence as a key to their advancement: the right for women to divorce, women’s fair custody of their children, birth control for women, equal pay for women and equal inclusion of Aboriginal women in Australian society. She understood the power of working with women throughout the world. Among her many accomplishments, Jessie Street championed the creation of the Commission on the Status of Women as a permanent United Nations body to deal with women’s rights. We’re proud she did. Australia has continued its meaningful engagement in international fora. In particular, we demonstrate our commitment and leadership on gender equality at home and abroad. 1 CEDAW OPENING STATEMENT As a long-standing signatory to CEDAW, current member of the Human Rights Council, and member of the Commission on the Status of Women starting next year, Australia places great importance on meeting our obligations under the Convention, and our delegation will do our best to answer your questions today. -

Edith Cowan College Your Pathway to ECU ECC Your Pathway to EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY 2017/18

2017/18 Perth, Australia Study at Edith Cowan College Your Pathway to ECU ECC Your pathway to EDITH COWAN UNIVERSITY 2017/18 Your future starts here • Edith Cowan College (ECC) provides pathway programs to Edith Cowan University (ECU), delivering a range of programs designed to provide a high quality education so that you are university-ready. • ECC students receive individual attention from their lecturers in smaller classes than the university, with access to high quality English language programs and additional free study support programs. ECC is located on ECU’s campus, providing students with access to the university’s state-of-the-art facilities including biology labs, computer labs, engineering ECU has been labs, lecture rooms and library. • ECC has embedded employability and English ranked the language skills within its programs so that you can reach your potential and ‘get that job’. This ensures that graduates are well prepared and attractive to top public university employers by standing out from other students. • ECC is focused on maximising your student experience with a range of social programs to help in Australia for you make lifelong friends and enjoy studying at ECC. Activities include barbecues, sporting activities (e.g. basketball, cricket, netball, soccer and volleyball) and student satisfaction help from your Student Leader. in the QILT (Quality Indicators • Read on to find out more about studying at ECC. for Learning and Teaching) in 2017. 1 Your pathway to a degree from Edith Cowan University Edith Cowan College (ECC) provides alternative pathways to Edith Cowan University (ECU) for students who may not qualify for direct entry into a degree program and are looking for a supportive learning environment. -

The Health and Welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: an Overview (Full Publication; 5 May

The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people an overview 2011 The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare is Australia’s national health and welfare statistics and information agency. The Institute’s mission is better information and statistics for better health and wellbeing. © Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced without prior written permission from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Head of the Communications, Media and Marketing Unit, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, GPO Box 570, Canberra ACT 2601. A complete list of the Institute’s publications is available from the Institute’s website <www.aihw.gov.au>. ISBN 978 1 74249 148 6 Suggested citation Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2011. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, an overview 2011. Cat. no. IHW 42. Canberra: AIHW. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Board Chair Hon. Peter Collins, AM, QC Director David Kalisch Any enquiries about or comments on this publication should be directed to: Communication, Media and Marketing Unit Australian Institute of Health and Welfare GPO Box 570 Canberra ACT 2601 Phone: (02) 6244 1032 Email: [email protected] Published by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Printed by Paragon Printers Australasia Please note that there is the potential for minor revisions of data in this report. Please check the online version at <www.aihw.gov.au> for any amendments. -

Jessie Street 1889-1970

Source: Discovering Democracy Lower Secondary Units – Political Life Biographies of four Australians who were politically active outside parliament http://www1.curriculum.edu.au/ddunits/units/ls4fq3acts.htm#Street Jessie Street 1889-1970 Some major achievements • Founder and President of the United Association of Women, 1929 • Only female member of the Australian delegation to the conference that set up the United Nations, 1945 • Drafter of the petition for a referendum to remove from the Australian Constitution the clauses that discriminated against Aboriginal people, 1964 Memorials and monuments • Jessie Street Women’s Library, Sydney • Jessie Street Garden, Sydney Lady Jessie Street Photograph by Falk. Courtesy National Library of Australia. Background and experience Jessie Lillingston came from a family of wealthy landowners in northern New South Wales. When she was a girl she loved horse riding but she did not like the fact that she was expected to ride side-saddle. So when nobody was looking, Jessie would swing her leg across the horse and ride the same way men did. All her life she behaved in ways that people from her background were not expected to behave. When she was a schoolgirl, Jessie met members of the suffragette movement in England and, on a visit to New York in 1915, she volunteered to help in a reception centre for young women arrested as prostitutes. In 1916, Jessie married Kenneth Street, who later became the highest judge in New South Wales. When he was knighted, she became Lady Jessie Street. • Ride side-saddle means to ride a horse with both feet on the same side of the horse. -

Life Itself’: a Socio-Historic Examination of FINRRAGE

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by White Rose E-theses Online From ‘Death of the Female’ to ‘Life Itself’: A Socio-Historic Examination of FINRRAGE Stevienna Marie de Saille Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy September 2012 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2012, The University of Leeds and Stevienna Marie de Saille The right of Stevienna Marie de Saille to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are a number of people who made this thesis possible in a number of different, fantastically important ways. My deepest thanks to: - My supervisors, Prof. Anne Kerr and Dr. Paul Bagguley, for their patience, advice, editorial comments, and the occasional kickstart when the project seemed just a little(!) overwhelming, and my examiners, Prof. Maureen McNeil and Dr. Angharad Beckett for their insight and suggestions. - The School of Sociology and Social Policy, for awarding me the teaching bursary which made this possible, and all the wonderful faculty and support staff who made it an excellent experience. - The archivists in Special Collections at the University of Leeds, and to the volunteers at the Feminist Archive North for giving me an all-access pass. -

Women's Political Participation and Representation in Asia

iwanaga The ability of a small elite of highly educated, upper-class Asian women’s political women to obtain the highest political positions in their country is unmatched elsewhere in the world and deserves study. But, for participation and those interested in a more detailed understanding of how women representation strive and sometimes succeed as political actors in Asia, there is a women’s marked lack of relevant research as well as of comprehensive and in asia user-friendly texts. Aiming to fill the gap is this timely and important study of the various obstacles and opportunities for women’s political Obstacles and Challenges participation and representation in Asia. Even though it brings political together a diverse array of prominent European and Asian academicians and researchers working in this field, it is nonetheless a singularly coherent, comprehensive and accessible volume. Edited by Kazuki Iwanaga The book covers a wide range of Asian countries, offers original data from various perspectives and engages the latest research on participation women in politics in Asia. It also aims to put the Asian situation in a global context by making a comparison with the situation in Europe. This is a volume that will be invaluable in women’s studies internationally and especially in Asia. a nd representation representation i n asia www.niaspress.dk Iwanaga-2_cover.indd 1 4/2/08 14:23:36 WOMEN’S POLITICAL PARTICIPATION AND REPRESENTATION IN ASIA Kazuki_prels.indd 1 12/20/07 3:27:44 PM WOMEN AND POLITICS IN ASIA Series Editors: Kazuki Iwanaga (Halmstad University) and Qi Wang (Oslo University) Women and Politics in Thailand Continuity and Change Edited by Kazuki Iwanaga Women’s Political Participation and Representation in Asia Obstacles and Challenges Edited by Kazuki Iwanaga Kazuki_prels.indd 2 12/20/07 3:27:44 PM Women’s Political Participation and Representation in Asia Obstacles and Challenges Edited by Kazuki Iwanaga Kazuki_prels.indd 3 12/20/07 3:27:44 PM Women and Politics in Asia series, No. -

Victorian Honour Roll of Women — Inspirational Women from All Walks of Life

+ + — — 2011 Victorian Honour Roll of Women — Inspirational women from all walks of life + — Published by: the Office of Women’s Policy Department of Human Services 1 Spring Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 Telephone. (03) 9208 3129 Online. www.women.vic.gov.au — March 2011. ©Copyright State of Victoria 2011. This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. — Authorised by the Victorian Government, Melbourne 2011 ISBN 978-0-7311-6346-5 — Designed by Studio Verse www.studioverse.com.au Printed by Gunn & Taylor Printers www.gunntaylor.com.au — Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an accessible format, such as large print or audio, please telephone 03 9208 3129. This publication is also published in PDF and Word formats on www.women.vic.gov.au — — 2011 Victorian Honour Roll of Women — — — Contents Inductee profiles — — — 03 05 17 Minister’s Foreword Professor Muriel Bamblett AM Aunty Dot Peters — — — 06 18 Terry Bracks Dr Wendy Poussard — — — 07 19 Cecilia Conroy Brenda Richards — — — 08 20 Sandie de Wolf AM Jane Scarlett AM — — — 09 21 Dale Fisher Carol Schwartz AM — — — 10 22 Dr Paula Gerber Virginia Simmons AO — — — 11 23 Tricia Harper AM Dr Diane Sisely — — — 12 24 Chris Jennings Dame Peggy van Praagh — — OBE, DBE 13 Jill Joslyn — — — 14 Betty Kitchener OAM — — — 15 Professor Jayashri Kulkarni — — — 16 Victorian Honour Roll Marion Lau OAM of Women 2001-2011 — — — Foreword Mary Wooldridge MP 03 Minister for Women’s Affairs — — — Professor Muriel Bamblett AM ‘ Aboriginal people constantly seek to make a difference in the lives of their community. -

Images of Women in Western Australian Politics: the Suffragist, Edith Cowan and Carmen Lawrence

Images of Women in Western Australian Politics: The Suffragist, Edith Cowan and Carmen Lawrence Dr. Joan Eveline Dept of Organisational and Labour Studies University ofWestern Australia and Dr Michael Booth Institute for Science and Technology Policy Murdoch University Paper delivered to Women's Worlds 99: 7th International Congress of Women's Research, Tromso, Norway, June 22, 1999 2 Images of Women in Western Australian Politics: The Suffragist, Edith Cowan and Carmen Lawrence Introduction 'Politics', claimed Carmen Lawrence in March, 1995, 'is a world in which you can easilybecome a caricature of yourself." In her own case, Lawrence's words were to prove prophetic. During the rest of 1995, only French nuclear testing and Bosnia rated more attention from the Australian press than the problems of this erstwhile state Premier and federal politician, and she was talkback radio's most popular topic for the year.' Although Carmen Lawrence does not specify gender as a significant aspect of the 'caricature effect', we do. Our paper explores the gender dimension in the 'public' construction and consumption of political figures, using the evidence ofpress and parliamentarycomment. Our focus is the portrayal of women in West Australian politics. In 1999, the state of Western Australia is celebrating the centenary of women's suffrage, and this paper is in part a response to those celebrations. Western Australia was second only to South Australia in granting women the vote, at a time when Australia and New Zealand were seen as leading the world in responding to demands for female suffrage. Out of a century of women's struggles we compare three figures, each of whose political participation has been represented as a breakthrough for women.