As with Many Convent Histories, Monson's Is Thankful for the Numerous Plates, Many of Which Circular

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vocal & Instrumental Music

Legrenzi Canto & Basso Vocal & Instrumental Music Ensemble Zenit Canto & Basso Vocal & Instrumental Music Giovanni Legrenzi 1626-1690 Giovanni Legrenzi Carlo Francesco Pollarolo 1653-1723 Giovanni Legrenzi 1. Sonata ‘La Foscari’ à 2 3’06 6. Sonata ‘La Colloreta’ à 2 2’56 11. Sonata No.2 del Pollaroli 12. Albescite flores à 4 6’14 from Sonate a due, e tre Op.2, from Sonate a due, e tre Op.2, di Venezia 2’54 from Harmonia d’affetti devoti, Venice 1655 Venice 1655 from Sonate da organo di varii Venice 1655 autori, Bologna 1697 Tarquinio Merula 1595-1665 7. Ave Regina coelorum à 2 4’39 2. Canzon di Tarquinio Merula 5’01 from Sentimenti devoti, Venice 1660 from Libro di Fra’ Gioseffo da Ravenna, Ravenna Classense Giovanni Paolo Colonna 1637-1695 Ensemble Zenit MS.545 8. Sonata No.7 del Colonna di Pietro Modesti cornetto · Fabio De Cataldo baroque trombone Bologna 4’31 Gilberto Scordari organ Giovanni Legrenzi from Sonate da organo di varii 3. Plaudite vocibus 5’55 autori, Bologna 1697 Isabella Di Pietro alto · Roberto Rilievi tenor from Acclamationi divote a voce sola, Bologna 1670 Giovanni Legrenzi 9. Suspiro Domine 7’46 4. Hodie collentatur Coeli à 2 6’09 from Acclamationi divote a voce from Harmonia d’affetti devoti, sola, Bologna 1670 Venice 1655 10 Sonata ‘La Donata’ à 2 4’05 Luigi Battiferri 1600-1682 from Sonate a due, e tre Op.2, 5. Ricercare Sesto. Venice 1655 Con due sogetti. 3’58 from Ricercari a quattro, a cinque, e a sei Op.3, Bologna 1699 This recording was made possible with the support of Recording: September 2018, Monastero -

Il Favore Degli Dei (1690): Meta-Opera and Metamorphoses at the Farnese Court

chapter 4 Il favore degli dei (1690): Meta-Opera and Metamorphoses at the Farnese Court Wendy Heller In 1690, Giovanni Maria Crescimbeni (1663–1728) and Gian Vincenzo Gravina (1664–1718), along with several of their literary colleagues, established the Arcadian Academy in Rome. Railing against the excesses of the day, their aim was to restore good taste and classical restraint to poetry, art, and opera. That same year, a mere 460 kilometres away, the Farnese court in Parma offered an entertainment that seemed designed to flout the precepts of these well- intentioned reformers.1 For the marriage of his son Prince Odoardo Farnese (1666–1693) to Dorothea Sofia of Neuberg (1670–1748), Duke Ranuccio II Farnese (1639–1694) spared no expense, capping off the elaborate festivities with what might well be one of the longest operas ever performed: Il favore degli dei, a ‘drama fantastico musicale’ with music by Bernardo Sabadini (d. 1718) and poetry by the prolific Venetian librettist Aurelio Aureli (d. 1718).2 Although Sabadini’s music does not survive, we are left with a host of para- textual materials to tempt the historical imagination. Aureli’s printed libretto, which includes thirteen engravings, provides a vivid sense of a production 1 The object of Crescimbeni’s most virulent condemnation was Giacinto Andrea Cicognini’s Giasone (1649), set by Francesco Cavalli, which Crescimbeni both praised as a most per- fect drama and condemned for bringing about the downfall of the genre. Mario Giovanni Crescimbeni, La bellezza della volgar poesia spiegata in otto dialoghi (Rome: Buagni, 1700), Dialogo iv, pp. -

Bach2000.Pdf

Teldec | Bach 2000 | home http://www.warnerclassics.com/teldec/bach2000/home.html 1 of 1 2000.01.02. 10:59 Teldec | Bach 2000 | An Introduction http://www.warnerclassics.com/teldec/bach2000/introd.html A Note on the Edition TELDEC will be the first record company to release the complete works of Johann Sebastian Bach in a uniformly packaged edition 153 CDs. BACH 2000 will be launched at the Salzburg Festival on 28 July 1999 and be available from the very beginning of celebrations to mark the 250th anniversary of the composer's death in 1750. The title BACH 2000 is a protected trademark. The artists taking part in BACH 2000 include: Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Gustav Leonhardt, Concentus musicus Wien, Ton Koopman, Il Giardino Armonico, Andreas Staier, Michele Barchi, Luca Pianca, Werner Ehrhardt, Bob van Asperen, Arnold Schoenberg Chor, Rundfunkchor Berlin, Tragicomedia, Thomas Zehetmair, Glen Wilson, Christoph Prégardien, Klaus Mertens, Barbara Bonney, Thomas Hampson, Herbert Tachezi, Frans Brüggen and many others ... BACH 2000 - A Summary Teldec's BACH 2000 Edition, 153 CDs in 12 volumes comprising Bach's complete works performed by world renowned Bach interpreters on period instruments, constitutes one of the most ambitious projects in recording history. BACH 2000 represents the culmination of a process that began four decades ago in 1958 with the creation of the DAS ALTE WERK label. After initially triggering an impassioned controversy, Nikolaus Harnoncourt's belief that "Early music is a foreign language which must be learned by musicians and listeners alike" has found widespread acceptance. He and his colleagues searched for original instruments to throw new light on composers and their works and significantly influenced the history of music interpretation in the second half of this century. -

9914396.PDF (12.18Mb)

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fece, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Ifigher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnaticn Compare 300 North Zeeb Road, Aim Arbor NO 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains pages with indistinct print. Pages were microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available UMI THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE TO THREE SACRED CHORAL/ ORCHESTRAL WORKS BY ANTONIO CALDARA: Magnificat in C. -

Winged Feet and Mute Eloquence: Dance In

Winged Feet and Mute Eloquence: Dance in Seventeenth-Century Venetian Opera Author(s): Irene Alm, Wendy Heller and Rebecca Harris-Warrick Source: Cambridge Opera Journal, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Nov., 2003), pp. 216-280 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3878252 Accessed: 05-06-2015 15:05 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3878252?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cambridge Opera Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.112.200.107 on Fri, 05 Jun 2015 15:05:41 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions CambridgeOpera Journal, 15, 3, 216-280 ( 2003 CambridgeUniversity Press DOL 10.1017/S0954586703001733 Winged feet and mute eloquence: dance in seventeenth-century Venetian opera IRENE ALM (edited by Wendy Heller and Rebecca Harris-Warrick) Abstract: This article shows how central dance was to the experience of opera in seventeenth-centuryVenice. -

Grand Finals Concert

NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Metropolitan Opera Carlo Rizzi National Council Auditions host Grand Finals Concert Anthony Roth Costanzo Sunday, March 31, 2019 3:00 PM guest artist Christian Van Horn Metropolitan Opera Orchestra The Metropolitan Opera National Council is grateful to the Charles H. Dyson Endowment Fund for underwriting the Council’s Auditions Program. general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals concert conductor Carlo Rizzi host Anthony Roth Costanzo guest artist Christian Van Horn “Dich, teure Halle” from Tannhäuser (Wagner) Meghan Kasanders, Soprano “Fra poco a me ricovero … Tu che a Dio spiegasti l’ali” from Lucia di Lammermoor (Donizetti) Dashuai Chen, Tenor “Oh! quante volte, oh! quante” from I Capuleti e i Montecchi (Bellini) Elena Villalón, Soprano “Kuda, kuda, kuda vy udalilis” (Lenski’s Aria) from Today’s concert is Eugene Onegin (Tchaikovsky) being recorded for Miles Mykkanen, Tenor future broadcast “Addio, addio, o miei sospiri” from Orfeo ed Euridice (Gluck) over many public Michaela Wolz, Mezzo-Soprano radio stations. Please check “Seul sur la terre” from Dom Sébastien (Donizetti) local listings. Piotr Buszewski, Tenor Sunday, March 31, 2019, 3:00PM “Captain Ahab? I must speak with you” from Moby Dick (Jake Heggie) Thomas Glass, Baritone “Don Ottavio, son morta! ... Or sai chi l’onore” from Don Giovanni (Mozart) Alaysha Fox, Soprano “Sorge infausta una procella” from Orlando (Handel) -

La Divisione Del Mondo Giovanni Legrenzi

STRASBOURG Opéra 8 > 16 février MULHOUSE La Sinne 2018 / 2019 1 et 3 mars • E COLMAR Théâtre SS 9 mars IER DE PRE IER SS DO la divisione del mondo giovanni legrenzi / P. 1 DOSSIER DE PRESSE DOSSIER du rhin opéra d'europe MONDO / DIVISIONE DEL LA © la fabrique des regards fabrique © la la divisione del mondo • gioVANNI LEGRENZI Opéra en trois actes Livret de Giulio Cesare Corradi Créé le 4 février 1675 à Venise Coproduction avec l’Opéra national de Lorraine [ nouveLLE PRODUction ] création française STRASBOURG Direction musicale Christophe Rousset Opéra Mise en scène Jetske Mijnssen Décors ve 8 février 20 h Herbert Murauer Costumes di 10 février 15 h Julia Katharina Berndt Lumières ma 12 février 20 h Bernd Purkrabek je 14 février 20 h Giove sa 16 février 20 h Carlo Allemano Nettuno Stuart Jackson Plutone Andre Morsch MULHOUSE Saturno Arnaud Richard La Sinne Giunone Julie Boulianne ve 1 mars 20 h Venere Sophie Junker di 3 mars 15 h Apollo Jake Arditti Amore Ada Elodie Tuca Marte Christopher Lowrey COLMAR Cintia Soraya Mafi Théâtre Mercurio Rupert Enticknap sa 9 mars 20 h Discordia Alberto Miguélez Rouco En langue italienne Les Talens Lyriques Surtitrages Publié par les éditions Balthasar Neumann / Édité par Thomas Hengelbrock en français et en allemand / P. 2 Durée du spectacle 2 h 45 environ entracte après l’Acte II PROLOGUE OPÉRA RENCONTRE BONSOIR MAESTRo ! 1 h avant chaque DE PRESSE DOSSIER Christophe Rousset avec l’équipe artistique représentation : sa 2 février 18 h à la librairie Kléber une introduction Strasbourg Opéra je 7 février à 18 h de 30 minutes Strasbourg > Salle Bastide entrée libre > Salle Paul Bastide entrée libre Mulhouse La Filature > Salle Jean Besse Colmar Théâtre entrée libre avec le soutien de MONDO / DIVISIONE DEL LA fidelio association pour le développement de l'Opéra national du Rhin l’œuvre en deux mots.. -

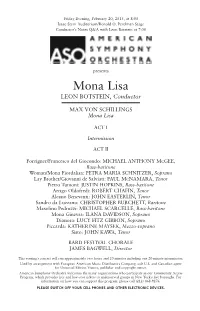

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

The Trio Sonata in 17Th-Century Italy LONDON BAROQUE

The Trio Sonata in 17th-Century Italy LONDON BAROQUE Pietro Novelli (1603 – 47): ‘Musical Duel between Apollo and Marsyas’ (ca. 1631/32). Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen, France. BIS-1795 BIS-1795_f-b.indd 1 2012-08-20 16.40 London Baroque Ingrid Seifert · Charles Medlam · Steven Devine · Richard Gwilt Photo: © Sioban Coppinger CIMA, Giovanni Paolo (c. 1570–1622) 1 Sonata a Tre 2'56 from Concerti ecclesiastici… e sei sonate per Instrumenti a due, tre, e quatro (Milan, 1610) TURINI, Francesco (c. 1589–1656) 2 Sonata a Tre Secondo Tuono 5'57 from Madrigali a una, due… con alcune sonate a due e tre, libro primo (Venice, 1621/24) BUONAMENTE, Giovanni Battista (c. 1595–1642) 3 Sonata 8 sopra La Romanesca 3'25 from Il quarto libro de varie Sonate… con Due Violini & un Basso di Viola (Venice 1626) CASTELLO, Dario (fl. 1st half 17th C) 4 Sonata Decima a 3, Due Soprani è Fagotto overo Viola 4'35 from Sonate concertate in stil moderno, libro secondo (Venice 1629) MERULA, Tarquinio (c. 1594–1665) 5 Chiaconna 2'32 from Canzoni overo sonate concertate… a tre… libro terza, Opus 12 (Venice 1637) UCCELLINI, Marco (c. 1603–80) 6 Sonata 26 sopra La Prosperina 3'16 from Sonate, correnti… con diversi stromenti… opera quarta (Venice 1645) FALCONIERO, Andrea (c. 1585–1656) 7 Folias echa para mi Señora Doña Tarolilla de Carallenos 3'17 from Il primo Libro di canzone, sinfonie… (Naples, 1650) 3 CAZZATI, Maurizio (1616–78) 8 Ciaconna 2'32 from Correnti e balletti… a 3. e 4., Opus 4 (Antwerp, 1651) MARINI, Biagio (1594–1663) 9 Sonata sopra fuggi dolente core 2'26 from Per ogni sorte d’stromento musicale… Libro Terzo. -

Scrivere Leggere Interpretare

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI TRIESTE SCRIVERE LEGGERE INTERPRETARE STUDI DI ANTICHITÀ IN ONORE DI SERGIO DARIS A CURA DI FRANCO CREVATIN E GENNARO TEDESCHI TRIESTE 2005 © Università degli Studi di Trieste - 2005 URL: www.sslmit.units.it/crevatin/franco_crevatin_homepage.htm In copertina foto di P.Daris inv. 98 (Alceo; Ia-Ip) Nota dei Curatori Ci sono momenti in cui dimensione accademica e fatti umani si intrecciano inestricabilmente: assieme ad altri Amici e Colleghi abbiamo desiderato fissare uno di tali momenti, nel quale la stima scientifica e la gratitudine per l’insegnamento ricevuto diventano parte della nostra storia condivisa. A Sergio Daris, che esce dai ruoli universitari, non occorre dire “arrivederci”, perché già sappiamo che la nostra consuetudine e lo scambio di idee continueranno come nel passato. F.C. G.T. I N D I C E ISABELLA ANDORLINI, Note di lettura ed interpretazione a PSI IV 299: un caso di tracoma, pp. 6 ANGELA ANDRISANO, La lettera overo discorso di G. Giraldi Cinzio sovra il comporre le satire atte alla scena: Tradizione aristotelica e innovazione, pp. 9 MARIA GABRIELLA ANGELI BERTINELLI – MARIA FEDERICA PETRACCIA LUCERNONI, Centurioni e curatori in ostraka dall'Egitto, pp. 44 GINO BANDELLI, Medea Norsa giovane, pp. 32 GUIDO BASTIANINI, Frammenti di una parachoresis a New York e Firenze (P.NYU inv. 22 + PSI inv. 137), pp. 6 MARCO BERGAMASCO, ¥(Upereth\j a)rxai=oj in POsl III 124, pp. 9 LAURA BOFFO, Per il lessico dell’archiviazione pubblica nel mondo greco. Note preliminari, pp. 4 FRANCESCO BOSSI, Adesp. Hell. 997a, 5 Ll.-J.-P., pp. 2 MARIO CAPASSO, Per l’itinerario della papirologia ercolanese, pp. -

DMA Document-Bergan -21-05-2020

EDVARD GRIEG Recognizing the Importance of the Nationalist Composer on the International Stage IPA Transliteration of Three Song Cycles D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Caroline Patricia Bergan, M.M., A.D. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Scott McCoy, Advisor Dr. Youkyung Bae Prof. Edward Bak Prof. Loretta Robinson Copyright by Caroline Patricia Bergan 2020 Abstract In North American colleges, universities, and conservatories it is not uncommon to find the main languages required of music students to be French, Italian, German, and English. Beyond the scope of these four most common languages, Russian, Spanish, and Czech are sung by more advanced or native singers of the languages; however, many other languages seem to be ignored in academia in both solo performance as well as in choral settings. It is a disservice to limit the scope of languages and repertoire when there exists a plethora of rarely performed compositions; moreover, it is not reasonable for these institutions to limit student's learning because of this “tradition.” Among the overlooked are the Scandinavian languages. This document will specifically address the repertoire of the most renowned Norwegian composer of the nineteenth century, Edvard Grieg (1843-1907). There exist but two published works that provide a singer with the resources to learn the pronunciation of curated Grieg selections. Neither of these resources was written by native Norwegian speakers; therefore, utilizing my linguistic skills as a native speaker and singer I intend this document to be a contribution toward the goal of providing near-native, accurate International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) transliterations of three song cycles representing Grieg's early, middle, and late writing. -

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Ospedale della Pietà in Venice Opernhaus Prag Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Complete Opera – Antonio Vivaldi – Complete Opera – Index - Complete Operas by Antonio Vivaldi Page Preface 3 Cantatas 1 RV687 Wedding Cantata 'Gloria e Imeneo' (Wedding cantata) 4 2 RV690 Serenata a 3 'Mio cor, povero cor' (My poor heart) 5 3 RV693 Serenata a 3 'La senna festegiante' 6 Operas 1 RV697 Argippo 7 2 RV699 Armida al campo d'Egitto 8 3 RV700 Arsilda, Regina di Ponto 9 4 RV702 Atenaide 10 5 RV703 Bajazet - Il Tamerlano 11 6 RV705 Catone in Utica 12 7 RV709 Dorilla in Tempe 13 8 RV710 Ercole sul Termodonte 14 9 RV711 Farnace 15 10 RV714 La fida ninfa 16 11 RV717 Il Giustino 17 12 RV718 Griselda 18 13 RV719 L'incoronazione di Dario 19 14 RV723 Motezuma 20 15 RV725 L'Olimpiade 21 16 RV726 L'oracolo in Messenia 22 17 RV727 Orlando finto pazzo 23 18 RV728 Orlando furioso 24 19 RV729 Ottone in Villa 25 20 RV731 Rosmira Fedele 26 21 RV734 La Silvia (incomplete) 27 22 RV736 Il Teuzzone 27 23 RV738 Tito Manlio 29 24 RV739 La verita in cimento 30 25 RV740 Il Tigrane (Fragment) 31 2 – Antonio Vivaldi – Complete Opera – Preface In 17th century Italy is quite affected by the opera fever. The genus just newly created is celebrated everywhere. Not quite. For in Romee were allowed operas for decades heard exclusively in a closed society. The Papal State, who wanted to seem virtuous achieved at least outwardly like all these stories about love, lust, passions and all the ancient heroes and gods was morally rather questionable.