FOLK HEALING PRACTICES of SIQUIJOR ISLAND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Language of Folk Healing Among Selected Ilocano Communities

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 9, Issue 10, October-2018 756 ISSN 2229-5518 THE LANGUAGE OF FOLK HEALING AMONG SELECTED ILOCANO COMMUNITIES Luzviminda P. Relon University of Northern Philippines Vigan City [email protected] ABSTRACT Folk healing in the Philippines reflects the deep-seated cultural beliefs and practices of ruralites. Traditionally, both affluent and poor families sought the help of traditional healers that may be called mangngilot, albularyo, mangngagas, agsantigwar, agtawas among others but are rendering similar services to the people. This study looked into the practices of folk healing at the same time, made an analysis on the frequently used Iloko words and how these Iloko words used in healing have changed and understood in the passing of years. Moreover, this study aimed also to shed light on the multiple functions that traditional healers are doing in the society. This is qualitative in nature which utilized the phenomenological design. Data were gathered from five traditional folk healers through KIM or Key Informant Mangngagas and Special Informants Pasyente (SIPs). It came out that while folk healers are instrumental in enriching the rich cultural beliefs and practices of typical Iloko community, they also contribute in propagating the present-day Ilocano terms or words which are commonly encountered during the healing process. It was validated that these are now rarely used by the younger generation in this fast changing society where technology has invaded the lives of people from all walks of life. Keywords: Culture, Qualitative Research, Ilocano, Northern Luzon, Traditional Healing IJSER Introduction human psyche. Traditional Healers see the universe as an living intelligence that Traditional Healing is the oldest operates according to natural laws that form of structured medicine. -

Philippine Folklore: Engkanto Beliefs

PHILIPPINE FOLKLORE: ENGKANTO BELIEFS HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: Philippine mythology is derived from Philippine folk literature, which is the traditional oral literature of the Filipino people. This refers to a wide range of material due to the ethnic mix of the Philippines. Each unique ethnic group has its own stories and myths to tell. While the oral and thus changeable aspect of folk literature is an important defining characteristic, much of this oral tradition had been written into a print format. University of the Philippines professor, Damiana Eugenio, classified Philippines Folk Literature into three major groups: folk narratives, folk speech, and folk songs. Folk narratives can either be in prose: the myth, the alamat (legend), and the kuwentong bayan (folktale), or in verse, as in the case of the folk epic. Folk speech includes the bugtong (riddle) and the salawikain (proverbs). Folk songs that can be sub-classified into those that tell a story (folk ballads) are a relative rarity in Philippine folk literature.1[1] Before the coming of Christianity, the people of these lands had some kind of religion. For no people however primitive is ever devoid of religion. This religion might have been animism. Like any other religion, this one was a complex of religious phenomena. It consisted of myths, legends, rituals and sacrifices, beliefs in the high gods as well as low; noble concepts and practices as well as degenerate ones; worship and adoration as well as magic and control. But these religious phenomena supplied the early peoples of this land what religion has always meant to supply: satisfaction of their existential needs. -

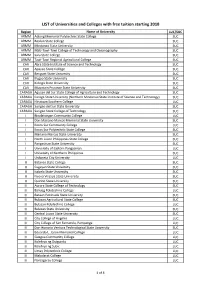

LIST of Universities and Colleges with Free Tuition Starting 2018

LIST of Universities and Colleges with free tuition starting 2018 Region Name of University LUC/SUC ARMM Adiong Memorial Polytechnic State College SUC ARMM Basilan State College SUC ARMM Mindanao State University SUC ARMM MSU-Tawi-Tawi College of Technology and Oceanography SUC ARMM Sulu State College SUC ARMM Tawi-Tawi Regional Agricultural College SUC CAR Abra State Institute of Science and Technology SUC CAR Apayao State College SUC CAR Benguet State University SUC CAR Ifugao State University SUC CAR Kalinga State University SUC CAR Mountain Province State University SUC CARAGA Agusan del Sur State College of Agriculture and Technology SUC CARAGA Caraga State University (Northern Mindanao State Institute of Science and Technology) SUC CARAGA Hinatuan Southern College LUC CARAGA Surigao del Sur State University SUC CARAGA Surigao State College of Technology SUC I Binalatongan Community College LUC I Don Mariano Marcos Memorial State University SUC I Ilocos Sur Community College LUC I Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College SUC I Mariano Marcos State University SUC I North Luzon Philippines State College SUC I Pangasinan State University SUC I University of Eastern Pangasinan LUC I University of Northern Philippines SUC I Urdaneta City University LUC II Batanes State College SUC II Cagayan State University SUC II Isabela State University SUC II Nueva Vizcaya State University SUC II Quirino State University SUC III Aurora State College of Technology SUC III Baliuag Polytechnic College LUC III Bataan Peninsula State University SUC III Bulacan Agricultural State College SUC III Bulacan Polytechnic College LUC III Bulacan State University SUC III Central Luzon State University SUC III City College of Angeles LUC III City College of San Fernando, Pampanga LUC III Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University SUC III Eduardo L. -

Higher Education in Agriculture Trends, Prospects, and Policy Directions

Higher Education in Agriculture Trends, Prospects, and Policy Directions Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Edited by Roehlano M. Briones Melvin B. Carlos Higher Education in Agriculture: Trends, Prospects, and Policy Directions Higher Education in Agriculture: Trends, Prospects, and Policy Directions Edited by Roehlano M. Briones Melvin B. Carlos Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development iii Copyright 2013 Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (PCAARRD) Printed in the Philippines. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of any individual or organization. Please do not quote without permission from the authors or PIDS and PCAARRD. Please address all inquiries to: Philippine Institute for Development Studies NEDA sa Makati Building, 106 Amorsolo Street Legaspi Village, 1229 Makati City, Philippines Tel: (63-2) 8939573 / 8942584 / 8935705 Fax: (63-2) 8161091 / 8939586 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.pids.gov.ph ISBN 978-971-564-062-6 RP 11-13-600 Copyeditor: Florisa Luna L. Carada Production Coordinator: Ivory Myka R. Galang and Claudette S. Malana Cover design: Jose Ignacio O. Tenorio Layout and printing: Bencel Z Press iv Table of Contents List of Tables, Figures, Box, and Annexes vi Foreword xiii Preface xvii Acknowledgment xix List of Acronyms xx Chapter 1 The state and future supply of and demand for Agriculture, Forestry 1 and Natural Resources (AFNR) graduates in the Philippines: Introduction Patricio S. -

Cultural Dynamics and the Church in the Philippines

Mulzac: Cultural Dynamics and the Church in the Philippines Cultural Dynamics and the Church in the Philippines The. overwhelming. Christian. majority. makes. the. Philippines. By.Kenneth.D..Mulzac the.only.country.that.is.predomi- nantly.Christian.in.Asia..Chris- tian behavior, however, is influ- enced.not.only.by.the.convictions. The. Philippines. consist. of. of.the.respective.faith.communi- 7,250.islands..About.700.of.these. ties. but. also. by. certain. unique. are. populated. with. about. 89.5. values. held. in. common. by. the. million. people,. at. an. average. Filipino.people..In.order.to.un- population. growth. rate. of. 1.8%.. derstand.the.Filipino.Christian,. These.citizens.represent.a.unique. these. values. must. be. acknowl- blend. of. diversity. (in. languages,. edged. and. appreciated. (Jocano. ethnicity,. and. cultures). and. ho- 1966b).. This. is. especially. true. mogeneity..Despite.this.diversity,. as. has. been. noted. by. one. Fili- one.common.element.that.charac- pino.thinker,.who.believes.that. terizes.Filipinos.is.a.deep.abiding. we.must.“know.the.sociological. interest.in.religion.that.permeates. and. psychological. traits. and. all. strata. of. society:. Christian- values. that. govern. Filipino. life.. ity.92.5%,.(comprised.of.Roman. Together,.these.traits.and.values. Catholics. 80.9%,. Evangelicals. contribute.to.the.development.of. 2.8%,. Iglesia. ni. Cristo. [Church. the.typical.Filipino.personality”. of.Christ].2.3%,.Philippine.Inde- (Castillo.1982:106,.107). pendent. or. Aglipayan. 2%,. other. Since. I. came. from. the. USA,. Christians.4.5%,);.Islam.5%;.other. a. highly. individualistic. society,. 1.8%;. unspecified. 0.6%;. none. I.wanted.to.understand.at.least. 0.1%.(World Factbook.2006). -

Revised Araling Sagisag Kultura Oct 27.Indd

ARALING SAGISAG KULTURA Grade 10 Semi- Detailed Culture-based Lesson Exemplar on Health Education Lana, Mananambal, Pasmo, Panghimasmo, Hilot, Patayhop Traditional Healing Practices and its Practitioners ni JUVILYN MIASCO ARALING SAGISAG KULTURA 113 I. INTRODUCTION Advancements in medical science and technology have benefitted many people. Most serious diseases can be cured, and many ill persons can be healed by modern medicine. However, there are still some Filipinos who believe in traditional medicine and consult local healers such as an albularyo, and a hilot. This lesson will help the students understand the cultural significance of healing practices in the Philippines and its local practitioners. II. OBJECTIVES General Safeguard one’s self and others by securing the right information about health products and services available in the communities. Day 1: Specific With 80% accuracy, the fourth year students are expected: Knowledge: • Define traditional medicine, pasmo, panghimasmo, albularyo, hilot and lana. • Identify the health benefits of traditional healing. Attitude: • Develop an appreciation of traditional healing practices. • Compare the western health practices and sanitation to traditional health practices. Skills: • Categorize the herbal plants according to its medicinal value. • Make a diagram of the procedure of panghimasmo. 114 ARALING SAGISAG KULTURA III. Materials/Resources References: • Grace Estela C. Mateo, PH.D., Agripino C. Darila, Lordinio A.Vergara • Enjoy Life with P.E. and Health IV, pp. 178-181 (Textbook) -

Philippine Mystic Dwarfs LUIS, Armand and Angel Meet Healing and Psychic Judge Florentino Floro

Philippine Mystic Dwarfs LUIS, Armand and Angel Meet Healing and Psychic Judge Florentino Floro by FLORENTINO V. FLORO, JR ., Part I - 2010 First Edition Published & Distributed by: FLORENTINO V. FLORO, JR . 1 Philippine Copyright© 2010 [Certificate of Copyright Registration and Deposit: Name of Copyright Owner and Author – Florentino V. Floro, Jr .; Date of Creation, Publication, Registration and Deposit – _________________, 2010, respectively; Registration No. __________, issued by the Republic of the Philippines, National Commission for Culture and the Arts, THE NATIONAL LIBRARY, Manila, Philippines, signed by Virginio V. Arrriero, Acting Chief, Publication and Special Services Division, for Director Prudencia C. Cruz, and Attested by Michelle A. Flor, 1 Copyright Examiner] By FLORENTINO V. FLORO, JR. Email: [email protected], 123 Dahlia, Alido, Bulihan, Malolos City, 3000 Bulacan, Philippines , Asia - Cel. # 0915 - 553008, Robert V. Floro All Rights Reserved This book is fully protected by copyright, and no part of it, with the exception of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews, may be reproduced, recorded, photocopied, or distributed in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or stored in a database or retrieved system, without the written consent of the Author/publisher. Any copy of this book not bearing a number and the signature of the Author on this page shall be denounced as proceeding from an illegal source, or is in possession of one who has no authority to dispose of the same. First Printing, 2010 Serial No. _____________ LCCCN, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: Floro, Florentino V., 2006, " Philippine Mystic Dwarves LUIS, Armand and Angel Meet Fortune-telling Judge", 1st edition, ____ p., FIL / ______ / ______ / 2010 2 ISBN ____________________ 3 Printed & Published by: FLORENTINO V. -

Shamanic Gender Liminality with Special Reference to the Natkadaw of Myanmar and the Bissu of Sulawesi

THE UNIVERSITY OF WALES, TRINITY ST. DAVID Shamanic gender liminality with special reference to the NatKadaw of Myanmar and the Bissu of Sulawesi. being a dissertation in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of M.A. in Social Anthropology at the University of Wales, Trinity St. David. AHAH7001 2013 Kevin Michael Purday Declaration Form Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form. 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed…… Date …….. 20th March 2013 2. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of M.A. in Social Anthropology. Signed ….. Date ……20th March 2013 3. This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed candidate: …. Date: ….20th March 2013 4. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying, inter-library loan, and for deposit in the University’s digital repository. Signed (candidate)…… Date……20th March 2013 Supervisor’s Declaration. I am satisfied that this work is the result of the student’s own efforts. Signed: ………………………………………………………………………….. Date: ……………………………………………………………………………... 1 List of contents Declaration Form ................................................................................................................ 1 List -

Cultural and Religious Dynamics of the Church in the Philippines1 Kenneth D

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 46, No. 1, 109-119. Copyright © 2008 Andrews University Press. CULTURAL AND RELIGIOUS DYNAMICS OF THE CHURCH IN THE PHILIPPINES1 KENNETH D. MULZAC Andrews University The Philippines consist of 7,250 islands. About 700 of these are populated with approximately 89.5 million people, at an average population growth rate of 1.8 percent per year. These citizens represent a unique blend of diversity (in languages, ethnicity, and cultures) and homogeneity.2 Despite this diversity, one common element that characterizes Filipinos is a deep abiding interest in religion that permeates all strata of society. Fully 99.3 percent of the population identify with a specific religion (see Table below).3 The overwhelming Christian majority makes the Philippines the only country in Asia that is predominantly Christian. Christian behavior, therefore, is influenced not only by the convictions of the respective faith communities, but also by certain psychosocial values held in common by the Filipino people. In order to understand the Filipino Christian, these values must be apprehended and appreciated.4 As one Filipino thinker has noted, we must 1I am writing as an outside observer. From September 2000 to November 2004, I taught religion at the Adventist International Institute of Advanced Studies, a graduate school owned and operated by the Seventh-day Adventist Church that is located in the Philippines. In an attempt to understand the Filipino mindset and possible response to teaching, preaching, and evangelism, I undertook this investigation. I discovered that this is a wide field that has been properly studied and documented, though in scattered places. -

Siquijor 2009

TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Siquijor Province i Map of Siquijor Attractions ii A. Overview I. Brief History................................................................... 1 II. Geographical & Topographical Features: Topographic................................................................. 1 Geographical Highlights............................................... 1 Coastal Area................................................................ 2 Aquatic........................................................................ 2 Other Characteristics................................................... 2 III. Climate........................................................................... 2 IV. Infrastructure: Transportation.Facilities.............................................. 3 Communication Facilities.............................................. 3 - 4 Power....................................................................... 4 Water........................................................................... 4 Health Facilities............................................................ 4 V. Economy: Agriculture................................................................... 4 Livestock & Poultry...................................................... 5 Forestry / Mineral Resources....................................... 5 Fish & Aquatic Resources.......................................... 5 Mining......................................................................... 5 Industries.................................................................... -

Ethnomedical Knowledge of Plants and Healthcare Practices Among the Kalanguya Tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, Philippines

Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge Vol. 10 (2), April 2011, pp. 227-238 Ethnomedical knowledge of plants and healthcare practices among the Kalanguya tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, Philippines Teodora D Balangcod 1* & Ashlyn Kim D Balangcod 2 1Department of Biology, College of Science, University of the Philippines Baguio; 2Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, College of Science, University of the Philippines Baguio E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] Received 17.11.2009; revised 09.04.2010 Tinoc, Ifugao is located within the Cordillera Central Range, Northern Luzon, Philippines. It is inhabited by the Kalanguya, one of the indigenous societies in the Cordillera, who have a long tradition of using medicinal plants. The paper describes ethnomedicinal importance of 125 plant species, and healthcare practices as cited by 150 informers ranging between 16-90 yrs. Various ailments that are treated by the identified medicinal plants vary from common diseases such as headache, stomachache, toothache, cough and colds, and skin diseases to more serious ailments which includes urinary tract infection, dysentery, and chicken pox. There are different modes of preparation of these medicinal plants. For instance, immediate treatment for cuts was demonstrated by using crushed leaves of Eupatorium adenophorum L. An increased efficacy was noted by creating mixtures from combining certain plants. The medicinal plants are summarized by giving their scientific name, family, vernacular name and utilization. Keywords: Ethnomedicine, Kalanguya, Medicinal plants, Traditional medicine, Philippines IPC Int. Cl. 8: A61K36/00, A61P1/10, A61P1/16, A61P9/14, A61P11/00, A61P13/00, A61P17/00, A61P19/00, A61P29/00, A61P31/02, A61P39/02 The relationship between man and plants is extremely source of medicine to treat different ailments. -

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

State Universities and Colleges (SUCs) Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Name of Receiving Officer Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link AIST Abra Institute of Science and Technology* http://www.asist.edu.ph/asistfoi.pdf AMPC Adiong Memorial Polytechnic College*** No Manual https://asscat.edu.ph/? Agusan Del Sur State College of Agriculture page_id=15#1515554207183-ef757d4a-bbef ASSCAT Office of the AMPC President Cristina P. Domingo 9195168755 and Technology http://asscat.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2018/FOI. pdf https://drive.google. ASU Aklan State University* com/file/d/0B8N4AoUgZJMHM2ZBVzVPWDVDa2M/ view ASC Apayao State College*** No Manual http://ascot.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/FOI. pdf ASCOT Aurora State College of Technology* cannot access site BSC Basilan State College*** No Manual http://www.bpsu.edu.ph/index.php/freedom-of- BPSU Bataan Peninsula State University* information/send/124-freedom-of-information- manual/615-foi2018 BSC Batanes State College* http://www.bscbatanes.edu.ph/FOI/FOI.pdf BSU Batangas State University* http://batstate-u.edu.ph/transparency-seal-2016/ 1st floor, University Public Administration Kara S. Panolong 074 422 2402 loc. 69 [email protected] Affairs Office Building, Benguet State University 2nd floor, Office of the Vice Administration Kenneth A. Laruan 63.74.422.2127 loc 16 President for [email protected] Building, Benguet Academic Affairs State University http://www.bsu.edu.ph/files/PEOPLE'S% BSU Benguet State University Office of the Vice 2nd floor, 20Manual-foi.pdf President for Administration Alma A. Santiago 63-74-422-5547 Research and Building, Benguet Extension State University 2nd floor, Office of the Vice Marketing Sheryl I.