Biographical Memoir by H E Rbe R T E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6799/positional-notation-or-trigonometry-2-13-106799.webp)

Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]

The Greatest Mathematical Discovery? David H. Bailey∗ Jonathan M. Borweiny April 24, 2011 1 Introduction Question: What mathematical discovery more than 1500 years ago: • Is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, single discovery in the field of mathematics? • Involved three subtle ideas that eluded the greatest minds of antiquity, even geniuses such as Archimedes? • Was fiercely resisted in Europe for hundreds of years after its discovery? • Even today, in historical treatments of mathematics, is often dismissed with scant mention, or else is ascribed to the wrong source? Answer: Our modern system of positional decimal notation with zero, to- gether with the basic arithmetic computational schemes, which were discov- ered in India prior to 500 CE. ∗Bailey: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. Email: [email protected]. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Computational and Technology Research, Division of Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. yCentre for Computer Assisted Research Mathematics and its Applications (CARMA), University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia. Email: [email protected]. 1 2 Why? As the 19th century mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace explained: It is India that gave us the ingenious method of expressing all numbers by means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit. But its very sim- plicity and the great ease which it has lent to all computations put our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions; and we shall appre- ciate the grandeur of this achievement the more when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest men produced by antiquity. -

The Original Version of This Chapter Was Revised: the Copyright Line Was Incorrect

The original version of this chapter was revised: The copyright line was incorrect. This has been corrected. The Erratum to this chapter is available at DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-35615-0_52 D. Passey et al. (eds.), TelE-Learning © IFIP International Federation for Information Processing 2002 62 Yakov I. Fet. scientists from CEE countries, including two distinguished Russian scientists, Sergey Lebedev, who 'designed and constructed the first computer in the Soviet Union and founded the Soviet computer industry' , and Aleksey Lyapunov, who 'developed the first theory of operator methods for abstract programming and founded Soviet cybernetics and programming' (IEEE Computer, 1998; IEE Annals of the History of Computing, 1999). Of course, this reward recognised the important contribution of scientists and engineers from Central and Eastern Europe who played a significant role. However, in our opinion, it was just the first step in exploring and publishing this contradictory history which is of particular interest. It can serve a critical lesson to teachers and students who should learn the truth about suppressing an understanding of cybernetics and other advanced modem sciences behind the 'iron curtain'. What can be done today in order to make familiar to the world computer community the true history of computer science in CEE countries? Recently, a special group of Russian experts started their investigations in this field. The first result of their efforts was the book 'Essays on the History of computer science in Russia' (Pospelov and Fet, 1998) published in 1998 in Novosibirsk, Russia. In contrast to historical and biographical writings reflecting to a great extent the personal views of their authors, this book is built completely on the basis of authentic documents of the epoch. -

A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Garrett Birkhoff has had a lifelong connection with Harvard mathematics. He was an infant when his father, the famous mathematician G. D. Birkhoff, joined the Harvard faculty. He has had a long academic career at Harvard: A.B. in 1932, Society of Fellows in 1933-1936, and a faculty appointmentfrom 1936 until his retirement in 1981. His research has ranged widely through alge bra, lattice theory, hydrodynamics, differential equations, scientific computing, and history of mathematics. Among his many publications are books on lattice theory and hydrodynamics, and the pioneering textbook A Survey of Modern Algebra, written jointly with S. Mac Lane. He has served as president ofSIAM and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Mathematics at Harvard, 1836-1944 GARRETT BIRKHOFF O. OUTLINE As my contribution to the history of mathematics in America, I decided to write a connected account of mathematical activity at Harvard from 1836 (Harvard's bicentennial) to the present day. During that time, many mathe maticians at Harvard have tried to respond constructively to the challenges and opportunities confronting them in a rapidly changing world. This essay reviews what might be called the indigenous period, lasting through World War II, during which most members of the Harvard mathe matical faculty had also studied there. Indeed, as will be explained in §§ 1-3 below, mathematical activity at Harvard was dominated by Benjamin Peirce and his students in the first half of this period. Then, from 1890 until around 1920, while our country was becoming a great power economically, basic mathematical research of high quality, mostly in traditional areas of analysis and theoretical celestial mechanics, was carried on by several faculty members. -

Equilmrium and DYNAMICS David Gale, 1991 Equilibrium and Dynamics

EQUILmRIUM AND DYNAMICS David Gale, 1991 Equilibrium and Dynamics Essays in Honour of David Gale Edited by Mukul Majumdar H. T. Warshow and Robert Irving Warshow Professor ofEconomics Cornell University Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-1-349-11698-0 ISBN 978-1-349-11696-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-11696-6 © Mukul Majumdar 1992 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1992 All rights reserved. For information, write: Scholarly and Reference Division, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 First published in the United States of America in 1992 ISBN 978-0-312-06810-3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Equilibrium and dynamics: essays in honour of David Gale I edited by Mukul Majumdar. p. em. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 978-0-312-06810-3 1. Equilibrium (Economics) 2. Statics and dynamics (Social sciences) I. Gale, David. II. Majumdar, Mukul, 1944- . HB145.E675 1992 339.5-dc20 91-25354 CIP Contents Preface vii Notes on the Contributors ix 1 Equilibrium in a Matching Market with General Preferences Ahmet Alkan 1 2 General Equilibrium with Infinitely Many Goods: The Case of Separable Utilities Aloisio Araujo and Paulo Klinger Monteiro 17 3 Regular Demand with Several, General Budget Constraints Yves Balasko and David Cass 29 4 Arbitrage Opportunities in Financial Markets are not Inconsistent with Competitive Equilibrium Lawrence M. Benveniste and Juan Ketterer 45 5 Fiscal and Monetary Policy in a General Equilibrium Model Truman Bewley 55 6 Equilibrium in Preemption Games with Complete Information Kenneth Hendricks and Charles Wilson 123 7 Allocation of Aggregate and Individual Risks through Financial Markets Michael J. -

From the Collections of the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton, NJ

From the collections of the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton, NJ These documents can only be used for educational and research purposes (“Fair use”) as per U.S. Copyright law (text below). By accessing this file, all users agree that their use falls within fair use as defined by the copyright law. They further agree to request permission of the Princeton University Library (and pay any fees, if applicable) if they plan to publish, broadcast, or otherwise disseminate this material. This includes all forms of electronic distribution. Inquiries about this material can be directed to: Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library 65 Olden Street Princeton, NJ 08540 609-258-6345 609-258-3385 (fax) [email protected] U.S. Copyright law test The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or other reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or other reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. The Princeton Mathematics Community in the 1930s Transcript Number 11 (PMC11) © The Trustees of Princeton University, 1985 MERRILL FLOOD (with ALBERT TUCKER) This is an interview of Merrill Flood in San Francisco on 14 May 1984. The interviewer is Albert Tucker. -

The Book Review Column1 by William Gasarch Department of Computer Science University of Maryland at College Park College Park, MD, 20742 Email: [email protected]

The Book Review Column1 by William Gasarch Department of Computer Science University of Maryland at College Park College Park, MD, 20742 email: [email protected] In this column we review the following books. 1. We review four collections of papers by Donald Knuth. There is a large variety of types of papers in all four collections: long, short, published, unpublished, “serious” and “fun”, though the last two categories overlap quite a bit. The titles are self explanatory. (a) Selected Papers on Discrete Mathematics by Donald E. Knuth. Review by Daniel Apon. (b) Selected Papers on Design of Algorithms by Donald E. Knuth. Review by Daniel Apon (c) Selected Papers on Fun & Games by Donald E. Knuth. Review by William Gasarch. (d) Companion to the Papers of Donald Knuth by Donald E. Knuth. Review by William Gasarch. 2. We review jointly four books from the Bolyai Society of Math Studies. The books in this series are usually collections of article in combinatorics that arise from a conference or workshop. This is the case for the four we review. The articles here vary tremendously in terms of length and if they include proofs. Most of the articles are surveys, not original work. The joint review if by William Gasarch. (a) Horizons of Combinatorics (Conference on Combinatorics Edited by Ervin Gyori,¨ Gyula Katona, Laszl´ o´ Lovasz.´ (b) Building Bridges (In honor of Laszl´ o´ Lovasz’s´ 60th birthday-Vol 1) Edited by Martin Grotschel¨ and Gyula Katona. (c) Fete of Combinatorics and Computer Science (In honor of Laszl´ o´ Lovasz’s´ 60th birthday- Vol 2) Edited by Gyula Katona, Alexander Schrijver, and Tamas.´ (d) Erdos˝ Centennial (In honor of Paul Erdos’s˝ 100th birthday) Edited by Laszl´ o´ Lovasz,´ Imre Ruzsa, Vera Sos.´ 3. -

Journal of Economics and Management

Journal of Economics and Management ISSN 1732-1948 Vol. 39 (1) 2020 Sylwia Bąk https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4398-0865 Institute of Economics, Finance and Management Faculty of Management and Social Communication Jagiellonian University, Cracow, Poland [email protected] The problem of uncertainty and risk as a subject of research of the Nobel Prize Laureates in Economic Sciences Accepted by Editor Ewa Ziemba | Received: June 27, 2019 | Revised: October 29, 2019 | Accepted: November 8, 2019. Abstract Aim/purpose – The main aim of the present paper is to identify the problem of uncer- tainty and risk in research carried out by the Nobel Prize Laureates in Economic Sciences and its analysis by disciplines/sub-disciplines represented by the awarded researchers. Design/methodology/approach – The paper rests on the literature analysis, mostly analysis of research achievements of the Nobel Prize Laureates in Economic Sciences. Findings – Studies have determined that research on uncertainty and risk is carried out in many disciplines and sub-disciplines of economic sciences. In addition, it has been established that a number of researchers among the Nobel Prize laureates in the field of economic sciences, take into account the issues of uncertainty and risk. The analysis showed that researchers selected from the Nobel Prize laureates have made a significant contribution to raising awareness of the importance of uncertainty and risk in many areas of the functioning of individuals, enterprises and national economies. Research implications/limitations – Research analysis was based on a selected group of scientific research – Laureates of the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. However, thus confirmed ground-breaking and momentous nature of the research findings of this group of authors justifies the selective choice of the analysed research material. -

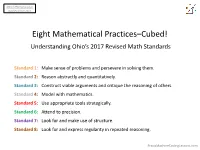

Eight Mathematical Practices–Cubed! Understanding Ohio’S 2017 Revised Math Standards

NWO STEM Symposium Bowling Green 2017 Eight Mathematical Practices–Cubed! Understanding Ohio’s 2017 Revised Math Standards Standard 1: Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. Standard 2: Reason abstractly and quantitatively. Standard 3: Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others. Standard 4: Model with mathematics. Standard 5: Use appropriate tools strategically. Standard 6: Attend to precision. Standard 7: Look for and make use of structure. Standard 8: Look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning. PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Exploring What’s New in Ohio’s 2017 Revised Math Standards • No Revisions to Math Practice Standards. • Minor Revisions to Grade Level and/or Content Standards. • Revisions Clarify and/or Lighten Required Content. Drill-Down Some Old/New Comparisons… PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Clarify Kindergarten Counting: PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Lighten Adding 5th Grade Fractions: PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Lighten Solving High School Quadratics: PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Ohio 2017 Math Practice Standard #1 1. Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. Mathematically proficient students start by explaining to themselves the meaning of a problem and looking for entry points to its solution. They analyze givens, constraints, relationships, and goals. They make conjectures about the form and meaning of the solution and plan a solution pathway rather than simply jumping into a solution attempt. They consider analogous problems, and try special cases and simpler forms of the original problem in order to gain insight into its solution. They monitor and evaluate their progress and change course if necessary. Older students might, depending on the context of the problem, transform algebraic expressions or change the viewing window on their graphing calculator to get the information they need. -

Federal Regulatory Management of the Automobile in the United States, 1966–1988

FEDERAL REGULATORY MANAGEMENT OF THE AUTOMOBILE IN THE UNITED STATES, 1966–1988 by LEE JARED VINSEL DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences of Carnegie Mellon University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Carnegie Mellon University May 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor David A. Hounshell, Chair Professor Jay Aronson Professor John Soluri Professor Joel A. Tarr Professor Steven Usselman (Georgia Tech) © 2011 Lee Jared Vinsel ii Dedication For the Vinsels, the McFaddens, and the Middletons and for Abigail, who held the ship steady iii Abstract Federal Regulatory Management of the Automobile in the United States, 1966–1988 by LEE JARED VINSEL Dissertation Director: Professor David A. Hounshell Throughout the 20th century, the automobile became the great American machine, a technological object that became inseparable from every level of American life and culture from the cycles of the national economy to the passions of teen dating, from the travails of labor struggles to the travels of “soccer moms.” Yet, the automobile brought with it multiple dimensions of risk: crashes mangled bodies, tailpipes spewed toxic exhausts, and engines “guzzled” increasingly limited fuel resources. During the 1960s and 1970s, the United States Federal government created institutions—primarily the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration within the Department of Transportation and the Office of Mobile Source Pollution Control in the Environmental Protection Agency—to regulate the automobile industry around three concerns, namely crash safety, fuel efficiency, and control of emissions. This dissertation examines the growth of state institutions to regulate these three concerns during the 1960s and 1970s through the 1980s when iv the state came under fire from new political forces and governmental bureaucracies experienced large cutbacks in budgets and staff. -

Macroeconomic Dynamics at the Cowles Commission from the 1930S to the 1950S

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Cowles Foundation Discussion Papers Cowles Foundation 9-1-2019 Macroeconomic Dynamics at the Cowles Commission from the 1930s to the 1950s Robert W. Dimand Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/cowles-discussion-paper-series Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Dimand, Robert W., "Macroeconomic Dynamics at the Cowles Commission from the 1930s to the 1950s" (2019). Cowles Foundation Discussion Papers. 56. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/cowles-discussion-paper-series/56 This Discussion Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Cowles Foundation at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cowles Foundation Discussion Papers by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MACROECONOMIC DYNAMICS AT THE COWLES COMMISSION FROM THE 1930S TO THE 1950S By Robert W. Dimand May 2019 COWLES FOUNDATION DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 2195 COWLES FOUNDATION FOR RESEARCH IN ECONOMICS YALE UNIVERSITY Box 208281 New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8281 http://cowles.yale.edu/ Macroeconomic Dynamics at the Cowles Commission from the 1930s to the 1950s Robert W. Dimand Department of Economics Brock University 1812 Sir Isaac Brock Way St. Catharines, Ontario L2S 3A1 Canada Telephone: 1-905-688-5550 x. 3125 Fax: 1-905-688-6388 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: macroeconomic dynamics, Cowles Commission, business cycles, Lawrence R. Klein, Tjalling C. Koopmans Abstract: This paper explores the development of dynamic modelling of macroeconomic fluctuations at the Cowles Commission from Roos, Dynamic Economics (Cowles Monograph No. -

FOCUS August/September 2005

FOCUS August/September 2005 FOCUS is published by the Mathematical Association of America in January, February, March, April, May/June, FOCUS August/September, October, November, and Volume 25 Issue 6 December. Editor: Fernando Gouvêa, Colby College; [email protected] Inside Managing Editor: Carol Baxter, MAA 4 Saunders Mac Lane, 1909-2005 [email protected] By John MacDonald Senior Writer: Harry Waldman, MAA [email protected] 5 Encountering Saunders Mac Lane By David Eisenbud Please address advertising inquiries to: Rebecca Hall [email protected] 8George B. Dantzig 1914–2005 President: Carl C. Cowen By Don Albers First Vice-President: Barbara T. Faires, 11 Convergence: Mathematics, History, and Teaching Second Vice-President: Jean Bee Chan, An Invitation and Call for Papers Secretary: Martha J. Siegel, Associate By Victor Katz Secretary: James J. Tattersall, Treasurer: John W. Kenelly 12 What I Learned From…Project NExT By Dave Perkins Executive Director: Tina H. Straley 14 The Preparation of Mathematics Teachers: A British View Part II Associate Executive Director and Director By Peter Ruane of Publications: Donald J. Albers FOCUS Editorial Board: Rob Bradley; J. 18 So You Want to be a Teacher Kevin Colligan; Sharon Cutler Ross; Joe By Jacqueline Brennon Giles Gallian; Jackie Giles; Maeve McCarthy; Colm 19 U.S.A. Mathematical Olympiad Winners Honored Mulcahy; Peter Renz; Annie Selden; Hortensia Soto-Johnson; Ravi Vakil. 20 Math Youth Days at the Ballpark Letters to the editor should be addressed to By Gene Abrams Fernando Gouvêa, Colby College, Dept. of 22 The Fundamental Theorem of ________________ Mathematics, Waterville, ME 04901, or by email to [email protected]. -

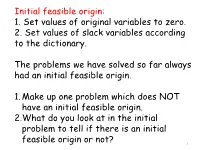

Initial Feasible Origin: 1. Set Values of Original Variables to Zero. 2. Set Values of Slack Variables According to the Dictionary

Initial feasible origin: 1. Set values of original variables to zero. 2. Set values of slack variables according to the dictionary. The problems we have solved so far always had an initial feasible origin. 1. Make up one problem which does NOT have an initial feasible origin. 2.What do you look at in the initial problem to tell if there is an initial feasible origin or not? 1 Office hours: MWR 4:20-5:30 inside or just outside Elliott 162- tell me in class that you would like to attend. For those of you who cannot stay: MWR: 1:30-2:30pm. But let me know 24 hours in advance you would like me to come in early. We will meet outside Elliott 162- Please estimate the length of time you require. I am also very happy to provide e-mail help: ([email protected]). Important note: to ensure your e-mail gets through the spam filter, use your UVic account. I answer all e-mails that I receive from my students. 2 George Dantzig: Founder of the Simplex method. http://wiki.hsc.com/wiki/Main/ConvexOptimization 3 In Dantzig’s own words: During my first year at Berkeley I arrived late one day to one of Neyman's classes. On the blackboard were two problems which I assumed had been assigned for homework. I copied them down. A few days later I apologized to Neyman for taking so long to do the homework - the problems seemed to be a little harder to do than usual. I asked him if he still wanted the work.