Challenges of Multilingualism in the EU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language, Culture, and National Identity

Language, Culture, and National Identity BY ERIC HOBSBAWM LANGUAGE, culture, and national identity is the ·title of my pa per, but its central subject is the situation of languages in cul tures, written or spoken languages still being the main medium of these. More specifically, my subject is "multiculturalism" in sofar as this depends on language. "Nations" come into it, since in the states in which we all live political decisions about how and where languages are used for public purposes (for example, in schools) are crucial. And these states are today commonly iden tified with "nations" as in the term United Nations. This is a dan gerous confusion. So let me begin with a few words about it. Since there are hardly any colonies left, practically all of us today live in independent and sovereign states. With the rarest exceptions, even exiles and refugees live in states, though not their own. It is fairly easy to get agreement about what constitutes such a state, at any rate the modern model of it, which has become the template for all new independent political entities since the late eighteenth century. It is a territory, preferably coherent and demarcated by frontier lines from its neighbors, within which all citizens without exception come under the exclusive rule of the territorial government and the rules under which it operates. Against this there is no appeal, except by authoritarian of that government; for even the superiority of European Community law over national law was established only by the decision of the constituent SOCIAL RESEARCH, Vol. -

Globalization and Language Policies of Multilingual Societies

Globalization and Language Policies of Multilingual Societies: Some Case Studies of South East Asia Globalização e políticas linguísticas em sociedades multilíngues: Estudos de caso do sudeste da Asia Navin Kumar Singh* Northern Arizona University Flagstaff / USA Shaoan Zhang** University of Nevada Las Vegas / USA Parwez Besmel*** Northern Arizona University Flagstaff / USA ABSTRACT: Over the past few decades, significant economic and political changes have taken place around the world. These changes also have put a significant mark on language teaching and learning practices across the globe. There is a clear movement towards multilingual practices in the world, which is also evident in the title of UNESCO 2003 education position paper, “Education in a multilingual world.” Given the long-standing history of multilingual contexts of the Himalayan region and the emergence of the two major global economic power centers of 21st century, China and India, language policies and practices of the region have become a great matter of interests for linguists and policy makers around the world. This paper uses case studies to investigate how globalization influences language education policies and practices in multilingual countries. The case studies that we have drawn from the four nations of South East Asia – Afghanistan, China, India, and Nepal offer insights for other multilingual nations of the world, as they portray the influences of globalization on language policies and practices of multilingual countries. This paper suggests more research on comparative studies of multilingual education across multilingual nations in the world. KEYWORDS: Language maintenance, globalization, multilingualism, Asian societies. * [email protected] ** [email protected] *** [email protected] RBLA, Belo Horizonte, v. -

Language Release, Which Will Be on August 2, 2017

Catalogue no. 98-501-X2016005 ISBN 978-0-660-07176-3 Release and concepts overview 2016 Census of Population: Language Release date: June 16, 2017 How to obtain more information For information about this product or the wide range of services and data available from Statistics Canada, visit our website, www.statcan.gc.ca. You can also contact us by email at [email protected] telephone, from Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., at the following numbers: • Statistical Information Service 1-800-263-1136 • National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1-800-363-7629 • Fax line 1-514-283-9350 Depository Services Program • Inquiries line 1-800-635-7943 • Fax line 1-800-565-7757 Standards of service to the public Standard table symbols Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, The following symbols are used in Statistics Canada reliable and courteous manner. To this end, Statistics Canada has publications: developed standards of service that its employees observe. To . not available for any reference period obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics .. not available for a specific reference period Canada toll-free at 1-800-263-1136. The service standards are ... not applicable also published on www.statcan.gc.ca under “Contact us” > 0 true zero or a value rounded to zero “Standards of service to the public.” 0s value rounded to 0 (zero) where there is a meaningful distinction between true zero and the value that was rounded p preliminary Note of appreciation r revised Canada owes the success of its statistical system to a x suppressed to meet the confidentiality requirements long-standing partnership between Statistics Canada, the of the Statistics Act citizens of Canada, its businesses, governments and other E use with caution institutions. -

Multilingualism As a Cohesion Factor in the European Culture

MULTILINGUALISM AS A COHESION FACTOR IN THE EUROPEAN CULTURE 1. EUROPEAN LANGUAGES Many European languages have their origins in three Indo-European language groups: the Romance languages from the Latin of the Roman Empire; the Germanic languages, whose original language was spoken in Southern Scandinavia, and the Slavic languages, derived from the Protoslav branch, which existed for over 3000 years before evolving into a variety of other languages during the period between the VI-IX centuries AD1. In general, all the current languages in Europe settled during the Middle Ages. Until then, the various languages had evolved rapidly because there was only a small percentage of people who could read and write. With so few people being able to read, it was normal for languages to be passed from generation to generation orally, making its evolutional process more expedient than what it currently is today. Romance languages were, and still to this day are spoken mainly in Southwestern Europe and in Romania and Moldova (Spanish, French, Portuguese and Italian are Romance languages, as well as other languages that are not so widespread as Catalan or Sardinian). Germanic languages have their roots in Northern and Northwestern Europe, and in some areas of Central Europe; to this group belong German, Dutch, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish and Icelandic, as well as Frisian, which is considered a minority language. Slavic languages are spoken in Central Europe, the Balkans, Russia and West of Russia. Because the area suffered numerous invasions over several centuries, languages were strongly differentiated from each other, which is the reason for the current division into three distinct groups: Western, Eastern and Southern. -

Egypt: Toponymic Factfile

TOPONYMIC FACT FILE Egypt Country name Egypt1 State title Arab Republic of Egypt Name of citizen Egyptian Official language Arabic (ara2) مصر (Country name in official language 3(Mişr جمهورية مصر العربية (State title in official language (Jumhūrīyat Mişr al ‘Arabīyah Script Arabic Romanization System BGN/PCGN Romanization System for Arabic 1956 ISO-3166 country code (alpha- EG/EGY 2/alpha-3) Capital Cairo4 القاهرة (Capital in official language (Al Qāhirah Geographical Names Policy Geographical names in Egypt are found written in Arabic, which is the country’s official language. Where possible names should be taken from official Arabic-language Egyptian sources and romanized using the BGN/PCGN Romanization System for Arabic5. Roman-script resources are often available for Egypt; however, it should also be noted that, even on official Egyptian products, Roman-script forms may be encountered which are likely to differ from those arising from the application of the BGN/PCGN Romanization System for Arabic.6 There are conventional Roman-script or English-language names for many places in Egypt (see ‘Other significant locations’, p12), which can be used where appropriate. For instance, in an English text it would be preferable to refer to the capital of Egypt as Cairo, and perhaps include a reference to its romanized form (Al Qāhirah). PCGN usually recommends showing these English conventional names in brackets after 1 The English language conventional name Egypt comes from the Ancient Greek Aígyptos (Αἴγυπτος) which is believed to derive from Ancient Egyptian hut-ka-ptah, meaning “castle of the soul of Ptah”. 2 ISO 639-3 language codes are used for languages throughout this document. -

Official Language Bilingualism for Allophones in Canada: Exploring Future Research Callie Mady and Miles Turnbull

Official Language Bilingualism for Allophones in Canada: Exploring Future Research Callie Mady and Miles Turnbull This article offers a review of policy and research as they relate to Allophones and their access to French Second Official Language (FSOL) programs in English- dominant Canada. Possible areas of future research are woven throughout the re- view as questions emerge in the summary of relevant literature. Notre article comprend une recension des documents de politique et des projets de recherche concernant les Allophones inscrits aux programmes de français langue seconde et officielle (FLSO) au Canada. Tout au long de l’article, nous tis- sons une série de questions de recherche possible pour le futur comme elles ont émergé pendant le développement de la recension des écrits. The Canadian Constitution (Canada, Department of Justice, 1982) guaran- tees equal status to English and French as the official languages of Canada providing for federal government services in both languages. As such, many federal job opportunities at minimum are centered on official-language bilingualism. In addition to linguistic considerations, the federal govern- ment recognizes official-language bilingualism as vital to Canadian identity (Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages, 2006). The dual privileg- ing of English and French by way of commodity and identity (Heller, 2002), then, encourages immigrants to Canada to consider such proclamations as they establish themselves and reconstruct their identities (Blackledge & Pavlenko, 2001). As Canada moves forward with its agenda to promote linguistic duality and official-language bilingualism, it must consider the effect of the growing Allophone population. In 2000, former Commissioner of Official Languages Dyane Adam called for a clear research agenda relating to Allophones and language education in Canada; she recognized immigration as a challenge to official-language bilingualism (Office of the Commissioner of Official Lan- guages, 2000). -

Europaio: a Brief Grammar of the European Language Reconstruct Than the Individual Groupings

1. Introduction 1.1. The Indo-European 1. The Indo-European languages are a family of several hundred languages and dialects, including most of the major languages of Europe, as well as many in South Asia. Contemporary languages in this family include English, German, French, Spanish, Countries with IE languages majority in orange. In Portuguese, Hindustani (i.e., mainly yellow, countries in which have official status. [© gfdl] Hindi and Urdu) and Russian. It is the largest family of languages in the world today, being spoken by approximately half the world's population as their mother tongue, while most of the other half speak at least one of them. 2. The classification of modern IE dialects into languages and dialects is controversial, as it depends on many factors, such as the pure linguistic ones (most of the times being the least important of them), the social, economic, political and historical ones. However, there are certain common ancestors, some of them old, well-attested languages (or language systems), as Classic Latin for Romance languages (such as French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Rumanian or Catalan), Classic Sanskrit for the Indo-Aryan languages or Classic Greek for present-day Greek. Furthermore, there are other, still older -some of them well known- dialects from which these old language systems were derived and later systematized, which are, following the above examples, Archaic Latin, Archaic Sanskrit and Archaic Greek, also attested in older compositions and inscriptions. And there are, finally, old related dialects which help develop a Proto-Language, as the Faliscan (and Osco-Umbrian for many scholars) for Latino-Faliscan (Italic for many), the Avestan for Indo-Iranian or the Mycenaean for Proto-Greek. -

The Arabic Language: a Latin of Modernity? Tomasz Kamusella University of St Andrews

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics Volume 11 Issue 2 DOI 10.1515/jnmlp-2017-0006 The Arabic Language: A Latin of Modernity? Tomasz Kamusella University of St Andrews Abstract Standard Arabic is directly derived from the language of the Quran. The Ara- bic language of the holy book of Islam is seen as the prescriptive benchmark of correctness for the use and standardization of Arabic. As such, this standard language is removed from the vernaculars over a millennium years, which Arabic-speakers employ nowadays in everyday life. Furthermore, standard Arabic is used for written purposes but very rarely spoken, which implies that there are no native speakers of this language. As a result, no speech com- munity of standard Arabic exists. Depending on the region or state, Arabs (understood here as Arabic speakers) belong to over 20 different vernacular speech communities centered around Arabic dialects. This feature is unique among the so-called “large languages” of the modern world. However, from a historical perspective, it can be likened to the functioning of Latin as the sole (written) language in Western Europe until the Reformation and in Central Europe until the mid-19th century. After the seventh to ninth century, there was no Latin-speaking community, while in day-to-day life, people who em- ployed Latin for written use spoke vernaculars. Afterward these vernaculars replaced Latin in written use also, so that now each recognized European lan- guage corresponds to a speech community. -

Multilingualism in the United States: a Less Well-Known Source of Vitality in American Culture As an Issue of Social Justice and of Historical Memory

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE NANZAN REVIEW OF AMERICAN STUDIES Volume 31 (2009): 59-75 Proceedings of the NASSS 2009 Literature and Culture Multilingualism in the United States: A Less Well-Known Source of Vitality in American Culture as an Issue of Social Justice and of Historical Memory Werner SOLLORS HARVARD UNIVERSITY [The talk takes its point of departure from current signs of multilingualism in American Census 2000 and American culture, examines some “language rights” issues, and ends with an anthology that has collected cultural expression in America from the 17th century to today in languages other than English. I am grateful to Kelsey LeBuffe for her research assistance and to Professors Jun Furuya, Konomi Ara, Eric Muller, and Keiko Sakai for their comments.] I. The world now has more than six and a half billion inhabitants (on June 17, 2009, the estimate was exactly 6,787,163,241) who live in 193 countries and speak 6,912 languages (http://www.un.org/esa/population/unpop.htm, http://www.ethnologue.com/ethno_docs/distribution.asp?by=area). One could indulge in the fantasy that creating more nation states with only one single shared language would make for more harmony (“we have room but for one language,” Theodore Roosevelt famously said)―but from about 200 countries to nearly 7,000 languages is a long way to go. Of course, the vast majority of languages have very few speakers, making the average of 35 languages per country a misleading calculation. Yet the simple fact remains that most countries―even in Europe and America, the continents with the smallest number of languages―have speakers of more than one language. -

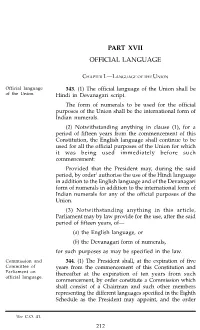

Part Xvii Official Language

PART XVII OFFICIAL LANGUAGE CHAPTER I.—LANGUAGE OF THE UNION Official language 343. (1) The official language of the Union shall be of the Union. Hindi in Devanagari script. The form of numerals to be used for the official purposes of the Union shall be the international form of Indian numerals. (2) Notwithstanding anything in clause (1), for a period of fifteen years from the commencement of this Constitution, the English language shall continue to be used for all the official purposes of the Union for which it was being used immediately before such commencement: Provided that the President may, during the said period, by order1 authorise the use of the Hindi language in addition to the English language and of the Devanagari form of numerals in addition to the international form of Indian numerals for any of the official purposes of the Union. (3) Notwithstanding anything in this article, Parliament may by law provide for the use, after the said period of fifteen years, of— (a) the English language, or (b) the Devanagari form of numerals, for such purposes as may be specified in the law. Commission and 344. (1) The President shall, at the expiration of five Committee of years from the commencement of this Constitution and Parliament on thereafter at the expiration of ten years from such official language. commencement, by order constitute a Commission which shall consist of a Chairman and such other members representing the different languages specified in the Eighth Schedule as the President may appoint, and the order 1See C.O. 41. 212 THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA 213 (Part XVII.—Official Language.—Art. -

Language Use in the United States: 2011 American Community Survey Reports

Language Use in the United States: 2011 American Community Survey Reports By Camille Ryan Issued August 2013 ACS-22 INTRODUCTION Figure 1. English is the language spoken by most people in the Reproduction of the Questions on United States. The official language of many states is Language From the 2011 American English1 and it is the language used in nearly all gov- Community Survey ernmental functions. Despite this predominance, many people in the United States speak languages other 14 a. Does this person speak a language other than than English, and there has long been an interest in English at home? these groups and in how well they are able to partici- Yes pate in civic life and interact with the English-speaking No SKIP to question 15a majority. Beginning in 1890, the U.S. Census Bureau started inquiring about the languages that people b. What is this language? spoke and, with some interruptions in the middle of the twentieth century, similar questions continue to this day. For example: Korean, Italian, Spanish, Vietnamese The primary purpose of the current questions c. How well does this person speak English? on language use is to measure the portion of the Very well U.S. population that may need help in understand- Well ing English. These data are used in a wide variety of Not well legislative, policy, and research applications as well as for legal, financial, and marketing decisions. People Not at all who speak a particular language other than English Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2011 American Community Survey. and cannot speak English “very well” can be helped with translation services, education, or assistance in President Clinton signed an executive order requir- accessing government services. -

Importance of Andhra Pradesh Mother Tongue-A Study on Telugu Language

RESEARCH PAPER SOCIAL SCIENCE Volume : 4 | Issue : 12 | Dec 2014 | ISSN - 2249-555X Importance of Andhra Pradesh Mother Tongue-a Study on Telugu Language KEYWORDS Andhra, Baasha, language, Telugu, Poet M. Venkatalakshmamma N. Munirathnamma Department of Telugu Studies, Sri Venkateswara Department of Telugu Studies, Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati-517 502, Andhra Pradesh, India. University, Tirupati-517 502, Andhra Pradesh, India. ABSTRACT Telugu is the most widely spoken language amongst those using the Brahmi script. These comprise the languages of south India (Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Kannada, Tulu and others such as Sinhala (spoken in Sri Lanka)and languages spoken in South East Asia such as Burmese, Thai and Cambodian) In terms of popula- tion, Telugu ranks second to Hindi among the Indian languages. The main languages spoken in Andhra Pradesh are Telugu, Urdu, Hindi, Banjara, and English followed by Tamil, Kannada, Marathi and Oriya. Telugu is the principal and official language of the State. It was also referred to as `Tenugu' in the past. `Andhra' is the name given to it since the medieval times. Some argued that `Telugu' was a corruption of `Trilinga' (Sanskrit meaning three `lingas'). Its vocabulary is very much influenced by Sanskrit. In the course of time, some Sanskrit expressions used in Telugu got so naturalized that people regarded them as pure Telugu words. INTRODUCTION poet called Telugu as “Sundara Telugu”. Telugu language has written literature from more than thousand years. The language which is spoken is called Nicolas called Telugu as “Italian of the east”. language. When there is development in language there will be development of society.