The Case for the North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Northern England City Called York Or Jorvik, During the Viking Age, Is Quite Medieval in Terms of Cultural History

History of York, England This northern England city called York or Jorvik, during the Viking age, is quite medieval in terms of cultural history. York is a tourist‐oriented city with its Roman and Viking heritage, 13th century walls, Gothic cathedrals, railroad station, museum‐gardens an unusual dinner served in a pub, and shopping areas in the Fossgate, Coppergate and Piccadilly area of the city. Brief History of York According to <historyofyork.org> (an extensive historical source), York's history began with the Romans founding the city in 71AD with the Ninth Legion comprising 5,000 men who marched into the area and set up camp. York, then was called, "Eboracum." After the Romans abandoned Britain in 400AD, York became known as "Sub Roman" between the period of 400 to 600AD. Described as an "elusive epoch," this was due to little known facts about that period. It was also a time when Germanic peoples, Anglo‐Saxons, were settling the area. Some archaeologists believe it had to do with devasting floods or unsettled habitation, due to a loss of being a trading center then. The rivers Ouse and Foss flow through York. <historyofyork.org> Christianity was re‐established during the Anglo‐Saxon period and the settlement of York was called "Eofonwic." It is believed that it was a commercial center tied to Lundenwic (London) and Gipeswic (Ipswich). Manufacturing associated with iron, lead, copper, wool, leather and bone were found. Roman roads made travel to and from York easier. <historyofyork.org> In 866AD, the Vikings attacked. Not all parts of England were captured, but York was. -

The Case of the National Identity Card in the UK Paul Beynon-Davies University of Wales, Swansea, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) European Conference on Information Systems ECIS 2005 Proceedings (ECIS) 2005 Personal Identification in the Information Age: The Case of the National Identity Card in the UK Paul Beynon-Davies University of Wales, Swansea, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2005 Recommended Citation Beynon-Davies, Paul, "Personal Identification in the Information Age: The asC e of the National Identity Card in the UK" (2005). ECIS 2005 Proceedings. 27. http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2005/27 This material is brought to you by the European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS) at AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). It has been accepted for inclusion in ECIS 2005 Proceedings by an authorized administrator of AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERSONAL IDENTIFICATION IN THE INFORMATION AGE: THE CASE OF THE NATIONAL IDENTITY CARD IN THE UK Paul Beynon-Davies, European Business Management School, University of Wales Swansea, Singleton Park, Swansea, UK, [email protected] Abstract The informatics infrastructure supporting the Information Society requires the aggregation of data about individuals in electronic records. Such data structures demand that individuals be uniquely identified and this is critical to the necessary processes of authentication, identification and enrolment associated with the use of e-Business, e-Government and potentially e-Democracy systems. It is also necessary to the representation of human interactions as data transactions supporting various forms of governance structure: hierarchies, markets and networks. -

North West of England Plan Regional Spatial Strategy to 2021 the North West of England Plan Regional Spatial Strategy to 2021

North West of England Plan Regional Spatial Strategy to 2021 The North West of England Plan Regional Spatial Strategy to 2021 London: TSO September 2008 Published by TSO (The Stationery Offi ce) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO Shops 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 71 Lothian Road, Edinburgh EH3 9AZ 0870 606 5566 Fax 0870 606 5588 TSO @ Blackwall and other Accredited Agents Communities and Local Government, Eland House, Bressenden Place, London SW1E 5DU Telephone 020 7944 4400 Web site www.communities.gov.uk © Crown Copyright 2008 Copyright in the typographical arrangements rests with the Crown. This publication, excluding logos, may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium for research, private study or for internal circulation within an organisation. This is subject to it being reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the publication specifi ed. For any other use of this material, please write to Licensing Division, Offi ce of Public Sector Information, 5th Floor, Pretty France, London SW1H 9AJ or e-mail: [email protected] Any queries relating to the content of this document should be referred to the Government Offi ce for the North West or the Regional Planning Body at the following address: Government Offi ce for North West, City Tower, Piccadilly Plaza, Manchester M1 4BE. -

Releasing Growth in Northern England's Sparse Areas

Releasing growth in northern sparse areas Roger Turner Rural Economies Consultant Northern region: City and Sparse Newcastle city: Sparse northern areas: 295,000 residents 305,000 people • 113 sq. km • 33% of north England’s territory (12,837 sq. km) • One Council – Newcastle • At least 15 Local City Council (NCC) authorities, 4 National Park Authorities, 4 Local Enterprise Partnerships • One Economic Strategy • No Single Economic for NCC and Gateshead Strategy for sparse areas Northern England’s sparsely populated region State of the countryside update: Sparsely populated areas. Commission for Rural Communities,2010 Economic challenges • 3 of England’s least productive economies [Northumberland <75%, East Cumbria 77% of UK mean) • High levels of economic inactivity, under employment, second jobs • High dependency on public sector jobs and their higher wages • Male wages on average 90% higher than those for women (ASHE 2009) • Markedly fewer residents in easy distances of health, education and retail services than other rural and urban areas • Low broadband speeds, poor mobile communication, limited business premises • National Policy leadership by Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs NOT Departments for Business, Work or Communities • Rural Development Programme for England seen as most critical support for area’s economic health, NOT European Social Fund, European Regional Development Programme and UK business growth programmes. Economic strengths • Higher levels of: – self employment, – firm survival rates, – residents -

England Northern Ireland Scotland Wales the Union Jack Flag

1 Pre-session 1: Existing Knowledge What do I know about the United Kingdom? 1 Session 1: What is the United Kingdom and where is it located? Key Knowledge ‘United’ means joined together. ‘Kingdom’ means a country ruled by a king or queen. The ‘United Kingdom’ is a union of four countries all ruled by Queen Elizabeth II. The four countries in the United Kingdom are: England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The United Kingdom is in the north-west of Europe. Key Words United Kingdom union north England country south Northern Ireland Europe east Scotland world west Wales Who is the person in this picture and what does she do? __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ 2 Can you label the four countries in the United Kingdom? The United Kingdom England Northern Ireland Scotland Wales England Northern Ireland Scotland Wales Challenge: Can you label the map to show where you live? 3 Can you find the United Kingdom and circle it on each of the maps? Map 1 Map 2 4 Map 3 Map 4 5 Map 5 Map 6 6 Session 2: What is it like to live in Scotland? Key Knowledge Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland. Edinburgh has a famous castle and is also the location of the Scottish Parliament. In the Highlands there are large mountains called Munros, valleys and enormous lakes called lochs. One of the deepest lakes in the UK is Loch Ness. Key Words Edinburgh Highlands capital mountains (munros) castle valleys parliament lakes (lochs) Glasgow Loch Ness rural Knowledge Quiz 4.1 1. United means… joined together split apart 2. -

Conference Programme Online Educa Berlin 2007

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Please see www.online-educa.com/pre-conference for Pre-Conference Workshops and Forums taking place on November 28 Please note that the agenda for Online Educa Berlin is subject to change (23 November 2007) Page 1 Session Codes & Themes COR = E-Learning in the Corporate and Company Context UNI = Learning Futures in Higher Education SCH = Classroom Learning and ICT PUB = Public and Professional E-Learning LIF = Lifelong and Informal Learning DES = Designing Teaching and Learning with Digital Media and Tools GAM = Games and Simulations in Support of Learning MOB = M-Learning: Learning in the Hands of the Learner WEB = Web 2.0 linked to Education 2.0 VID = Video in Support of Online Learning QUA = Quality and E-Learning EVA = Assessment and Evaluation ACC = Online Learning, Equality and Accessibility RES = The Application of Research Outcomes in the TEL Field POL = E-Learning Policy and Practice KES = Knowledge Exchange Sessions GEN = General Sessions BPS = Best Practice Sessions DEM = Demonstration Sessions NET = Networking Sessions Page 2 Thursday, November 29, 2007 9:15 – 11:00 Opening Plenary Potsdam I/III The Opening Plenary for Online Educa Berlin 2007 will be chaired by Dr. Harold Elletson, The New Security Foundation, UK and will feature key-note presentations by: Hon. Elizabeth Ohene, Minister of State, Ministry of Education, Science & Sports, Ghana Prof. Sugata Mitra, Newcastle University, UK & Chief Scientist Emeritus, NIIT Ltd., India The “Hole in the Wall” Experiments: Self-Organising Systems in Primary -

Members 1979-2010

Members 1979-2010 RESEARCH PAPER 10/33 28 April 2010 This Research Paper provides a complete list of all Members who have served in the House of Commons since the general election of 1979 to the dissolution of Parliament on 12 April 2010. The Paper also provides basic biographical and parliamentary data. The Library and House of Commons Information Office are frequently asked for such information and this Paper is based on the data we collate from published sources to assist us in responding. This Paper replaces an earlier version, Research Paper 09/31. Oonagh Gay Richard Cracknell Jeremy Hardacre Jean Fessey Recent Research Papers 10/22 Crime and Security Bill: Committee Stage Report 03.03.10 10/23 Third Parties (Rights Against Insurers) Bill [HL] [Bill 79 of 2009-10] 08.03.10 10/24 Local Authorities (Overview and Scrutiny) Bill: Committee Stage Report 08.03.10 10/25 Northern Ireland Assembly Members Bill [HL] [Bill 75 of 2009-10] 09.03.10 10/26 Debt Relief (Developing Countries) Bill: Committee Stage Report 11.03.10 10/27 Unemployment by Constituency, February 2010 17.03.10 10/28 Transport Policy in 2010: a rough guide 19.03.10 10/29 Direct taxes: rates and allowances 2010/11 26.03.10 10/30 Digital Economy Bill [HL] [Bill 89 of 2009-10] 29.03.10 10/31 Economic Indicators, April 2010 06.04.10 10/32 Claimant Count Unemployment in the new (2010) Parliamentary 12.04.10 Constituencies Research Paper 10/33 Contributing Authors: Oonagh Gay, Parliament and Constitution Centre Richard Cracknell, Social and General Statistics Section Jeremy Hardacre, Statistics Resources Unit Jean Fessey, House of Commons Information Office This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. -

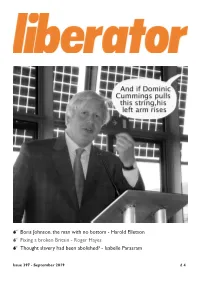

Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a Broken Britain

0 Boris Johnson, the man with no bottom - Harold Elletson 0 Fixing a broken Britain - Roger Hayes 0 Thought slavery had been abolished? - Isabelle Parasram Issue 397 - September 2019 £ 4 Issue 397 September 2019 SUBSCRIBE! CONTENTS Liberator magazine is published six/seven times per year. Subscribe for only £25 (£30 overseas) per year. Commentary .................................................................................3 You can subscribe or renew online using PayPal at Radical Bulletin .............................................................................4..5 our website: www.liberator.org.uk THE MAN WITH NO BOTTOM ................................................6..7 Or send a cheque (UK banks only), payable to Boris Johnson might see himself as a ’great man’, but is an empty vessel “Liberator Publications”, together with your name without values says former Tory MP Harold Elletson and full postal address, to: IT’S TIME FOR US TO FIX A BROKEN BRITAIN ....................8..9 After three wasted years and the possible horror of Brexit it’s time Liberator Publications for the Liberal Democrat to take the lead in creating a reformed Britain, Flat 1, 24 Alexandra Grove says Roger Hayes London N4 2LF England ANOTHER ALLIANCE? .............................................................10..11 Should there be a Remain Alliance involving Liberal Democrats at any imminent general election? Liberator canvassed some views, THE LIBERATOR this is what we got COLLECTIVE Jonathan Calder, Richard Clein, Howard Cohen, IS IT OUR FAULT? .....................................................................12..13 -

Northern Devolution Through the Lens of History

This is a repository copy of From problems in the North to the problematic North : Northern devolution through the lens of history. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/113610/ Book Section: Martin, Daryl orcid.org/0000-0002-5685-4553, Schafran, Alex and Taylor, Zac (2017) From problems in the North to the problematic North : Northern devolution through the lens of history. In: Berry, Craig and Giovannini, Arianna, (eds.) Developing England's North. Building a Sustainable Political Economy . Palgrave Macmillan . Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Submission for the WR Network book. DRAFT. DO NOT DISTRIBUTE From problems in the North to the problematic North: Northern devolution through the lens of history Daryl Martin, Department of Sociology, University of York Alex Schafran, School of Geography, University of Leeds Zac Taylor, School of Geography, University of Leeds Abstract: Current debates about Northern English cities and their role in national economic strategies cannot be read simply through the lens of contemporary politics. -

Membership Roll

FOR PERSONAL USE ONLY - NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω Ω MEMBERSHIP ROLL Illustrious Royal Order of Saint Januarius Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George Royal Order of Francis I DELEGATION OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND March 2015 The Grand Master HRH Prince Charles of Bourbon Two Sicilies, Duke of Castro, and HRH Princess Camilla of Bourbon Two Sicilies, Duchess of Castro, His Eminence Renato Raffaele, Cardinal Martino, Grand Prior of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George The Prayer of the Constantinian Order 1 The History of the Order in Great Britain 2 The History of the Order in Ireland 4 Council of the Delegation of Great Britain and Ireland 6 Members of the Delegation of Great Britain and Ireland 8 Illustrious Royal Order of Saint Januarius 8 » In the Category of Knight 8 Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George 9 » In the Category of Justice 9 » In the Special Category 10 » In the Category of Grace 10 » In the Category of Merit 12 » » In the Category of Office 15 RoyalRecepients Order of of BenemerentiFrancis I Medals 1715 Post Nominals of Decorations 20 Obituaries 21 The Prayer of the Constantinian Order Almighty and Merciful Father, King of kings and Lord of lords, in Your immeasurable goodness You have called me into the ranks of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George, Your Knight and Martyr. May I never cease to emulate our heavenly patron and with alacrity fol- low in the footsteps of Your Only-begotten Son, Who is our Alpha and Omega, our Beginning and End. -

Evidence Review

Greater Manchester: Evidence Review November 2018 Greater Manchester: Independent Prosperity Review Background Paper 1 The Greater Manchester Prosperity Review In the 2017 Autumn Budget and as part of the city region’s sixth devolution deal, Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) and Government agreed to work together to develop one of the UK’s first local industrial strategies. The GM Local Industrial Strategy will reflect the main themes of the national Industrial Strategy White Paper whilst taking a place- based approach that builds on the area’s unique strengths and ensures all people in Greater Manchester (GM) can contribute to, and benefit from, economic growth. A robust and credible evidence base is critical to underpin the Local Industrial Strategy and to make the case for what needs to be done to deliver growth for Greater Manchester and its residents. It will also be critical to ensure buy-in from local and national public and private stakeholders – building on the success of the Manchester Independent Economic Review (MIER)1 a decade ago. Development of the evidence base underpinning the Local Industrial Strategy is being taken forward under the Greater Manchester Independent Prosperity Review. The review is being led by a panel of independent experts chaired by Professor Diane Coyle (Bennett Professor of Public Policy, University of Cambridge). The other members of the panel are: Professor Ed Glaeser (Professor of Economics, Harvard University); Stephanie Flanders (Head of Bloomberg Economics); Professor Henry Overman (Professor of Economic Geography, London School of Economics); Professor Mariana Mazzucato (Professor in the Economics of Innovation, University College London); and Darra Singh (Government & Public Sector Lead at EY). -

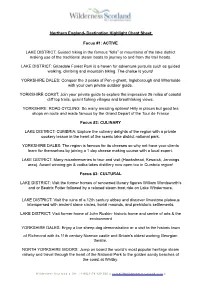

Northern England- Destination Highlight Cheat Sheet

Northern England- Destination Highlight Cheat Sheet Focus #1: ACTIVE LAKE DISTRICT: Guided hiking in the famous “fells” or mountains of the lake district making use of the traditional steam boats to journey to and from the trail heads. LAKE DISTRICT: Grizedale Forest Park is a haven for adventure pursuits such as guided walking, climbing and mountain biking. The choice is yours! YORKSHIRE DALES: Conquer the 3 peaks of Pen-y-ghent, Ingleborough and Whernside with your own private outdoor guide. YORKSHIRE COAST: Join your private guide to explore the impressive 26 miles of coastal cliff top trails, quaint fishing villages and breathtaking views. YORKSHIRE: ROAD CYCLING: So many amazing options! Hilly in places but good tea shops en route and made famous by the Grand Depart of the Tour de France Focus #2: CULINARY LAKE DISTRICT: CUMBRIA: Explore the culinary delights of the region with a private cookery lesson in the heart of the scenic lake district national park. YORKSHIRE DALES: The region is famous for its cheeses so why not have your clients learn for themselves by joining a 1 day cheese making course with a local expert. LAKE DISTRICT: Many microbreweries to tour and visit (Hawkshead, Keswick, Jennings area). Award winning gin & vodka lakes distillery now open too in Cumbria region! Focus #3: CULTURAL LAKE DISTRICT: Visit the former homes of renowned literary figures William Wordsworth’s and or Beatrix Potter followed by a relaxed steam boat ride on Lake Windermere. LAKE DISTRICT: Visit the ruins of a 12th century abbey and discover limestone plateaus interspersed with ancient stone circles, burial mounds, and prehistoric settlements.