The Destruction of the Christian Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Times (A.D

The Catholic Faith History of Catholicism A Brief History of Catholicism (Excerpts from Catholicism for Dummies) Ancient Times (A.D. 33-741) Non-Christian Rome (33-312) o The early Christians (mostly Jews who maintained their Jewish traditions) o Jerusalem’s religious establishment tolerated the early Christians as a fringe element of Judaism o Christianity splits into its own religion . Growing number of Gentile converts (outnumbered Jewish converts by the end of the first century) . Greek and Roman cultural influences were adapted into Christianity . Destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in A.D. 70 (resulted in the final and formal expulsion of the Christians from Judaism) o The Roman persecutions . The first period (A.D. 68-117) – Emperor Nero blamed Christians for the burning of Rome . The second period (A.D. 117-192) – Emperors were less tyrannical and despotic but the persecutions were still promoted . The third period (A.D. 193-313) – Persecutions were the most virulent, violent, and atrocious during this period Christian Rome (313-475) o A.D. 286 Roman Empire split between East and West . Constantinople – formerly the city of Byzantium and now present- day Istanbul . Rome – declined in power and prestige during the barbarian invasions (A.D. 378-570) while the papacy emerged as the stable center of a chaotic world o Roman Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in A.D. 313 which legalized Christianity – it was no longer a capital crime to be Christian o A.D. 380 Christianity became the official state religion – Paganism was outlawed o The Christian Patriarchs (Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, Rome, and Constantinople) . -

Antoine De Chandieu (1534-1591): One of the Fathers Of

CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): ONE OF THE FATHERS OF REFORMED SCHOLASTICISM? A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MAY 2013 CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 3233 Burton SE • Grand Rapids, Michigan • 49546-4301 800388-6034 fax: 616 957-8621 [email protected] www. calvinseminary. edu. This dissertation entitled ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): L'UN DES PERES DE LA SCHOLASTIQUE REFORMEE? written by THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has been accepted by the faculty of Calvin Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: Richard A. Muller, Ph.D. I Date ~ 4 ,,?tJ/3 Dean of Academic Programs Copyright © 2013 by Theodore G. (Ted) Van Raalte All rights reserved For Christine CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................. viii Abstract ................................................................................................................... xii Chapter 1 Introduction: Historiography and Scholastic Method Introduction .............................................................................................................1 State of Research on Chandieu ...............................................................................6 Published Research on Chandieu’s Contemporary -

Acta Apostolicae Sedis

ACTA APOSTOLICAE SEDIS COMMENTARIUM OFFICIALE ANNUS XII - VOLUMEN XII ROMAE TYPIS POLYGLOTTIS VATICANIS MCMXX fr fr Num. 1 ACTA APOSTOLICAE SEDIS COMMENTARIUM OFFICIALE ACTA BENEDICTI PP. XV CONSTITUTIO APOSTOLICA AGRENSIS ET PURUENSIS ERECTIO PRAELATURAE NULLIUS BENEDICTUS EPISCOPUS SERVUS SERVORUM DEI AD PERPETUAM REI MEMORIAM Ecclesiae universae regimen, Nobis ex alto commissum, onus Nobis imponit diligentissime curandi ut in orbe catholico circumscriptionum ecclesiasticarum numerus, ceu occasio vel necessitas postulat, augeatur, ut, coarctatis dioecesum finibus ac proinde minuto fidelium grege sin gulis Pastoribus credito, Praesules ipsi munus sibi commissum facilius ac salubrius exercere possint. Quum autem apprime constet dioecesim Amazonensem in Brasi liana Republica latissime patere, viisque quam maxime deficere, prae sertim in occidentali parte, in provinciis scilicet, quae Alto Aere et Alto Purus vocantur, ubi fideles commixti saepe saepius cum indigenis infidelibus vivunt et spiritualibus subsidiis, quibus christiana vita alitur et sustentatur, ferme ex integro carent; Nos tantae necessitati subve niendum duximus. Ideoque, collatis consiliis cum dilectis filiis Nostris S. R. E. Car dinalibus S. Congregationi Consistoriali praepositis, omnibusque mature perpensis, partem territorii dictae dioecesis Amazonensis, quod prae dictas provincias Alto Aere et Alto Purus complectitur, ab eadem dioe cesi distrahere et in Praelaturam Nullius erigere statuimus. 6 Acta Apostolicae Sedis - Commentarium Officiale Quamobrem, potestate -

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite

A Comparison of the Two Forms of the Roman Rite Mass Structures Orientation Language The purpose of this presentation is to prepare you for what will very likely be your first Traditional Latin Mass (TLM). This is officially named “The Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” We will try to do that by comparing it to what you already know - the Novus Ordo Missae (NOM). This is officially named “The Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite.” In “Mass Structures” we will look at differences in form. While the TLM really has only one structure, the NOM has many options. As we shall see, it has so many in fact, that it is virtually impossible for the person in the pew to determine whether the priest actually performs one of the many variations according to the rubrics (rules) for celebrating the NOM. Then, we will briefly examine the two most obvious differences in the performance of the Mass - the orientation of the priest (and people) and the language used. The orientation of the priest in the TLM is towards the altar. In this position, he is facing the same direction as the people, liturgical “east” and, in a traditional church, they are both looking at the tabernacle and/or crucifix in the center of the altar. The language of the TLM is, of course, Latin. It has been Latin since before the year 400. The NOM was written in Latin but is usually performed in the language of the immediate location - the vernacular. [email protected] 1 Mass Structure: Novus Ordo Missae Eucharistic Prayer Baptism I: A,B,C,D Renewal Eucharistic Prayer II: A,B,C,D Liturgy of Greeting: Penitential Concluding Dismissal: the Word: A,B,C Rite: A,B,C Eucharistic Prayer Rite: A,B,C A,B,C Year 1,2,3 III: A,B,C,D Eucharistic Prayer IV: A,B,C,D 3 x 4 x 3 x 16 x 3 x 3 = 5184 variations (not counting omissions) Or ~ 100 Years of Sundays This is the Mass that most of you attend. -

Mystici Corporis Christi

MYSTICI CORPORIS CHRISTI ENCYCLICAL OF POPE PIUS XII ON THE MISTICAL BODY OF CHRIST TO OUR VENERABLE BRETHREN, PATRIARCHS, PRIMATES, ARCHBISHOPS, BISHIOPS, AND OTHER LOCAL ORDINARIES ENJOYING PEACE AND COMMUNION WITH THE APOSTOLIC SEE June 29, 1943 Venerable Brethren, Health and Apostolic Benediction. The doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ, which is the Church,[1] was first taught us by the Redeemer Himself. Illustrating as it does the great and inestimable privilege of our intimate union with so exalted a Head, this doctrine by its sublime dignity invites all those who are drawn by the Holy Spirit to study it, and gives them, in the truths of which it proposes to the mind, a strong incentive to the performance of such good works as are conformable to its teaching. For this reason, We deem it fitting to speak to you on this subject through this Encyclical Letter, developing and explaining above all, those points which concern the Church Militant. To this We are urged not only by the surpassing grandeur of the subject but also by the circumstances of the present time. 2. For We intend to speak of the riches stored up in this Church which Christ purchased with His own Blood, [2] and whose members glory in a thorn-crowned Head. The fact that they thus glory is a striking proof that the greatest joy and exaltation are born only of suffering, and hence that we should rejoice if we partake of the sufferings of Christ, that when His glory shall be revealed we may also be glad with exceeding joy. -

Catholicism Episode 6

OUTLINE: CATHOLICISM EPISODE 6 I. The Mystery of the Church A. Can you define “Church” in a single sentence? B. The Church is not a human invention; in Christ, “like a sacrament” C. The Church is a Body, a living organism 1. “I am the vine and you are the branches” (Jn. 15) 2. The Mystical Body of Christ (Mystici Corporis Christi, by Pius XII) 3. Jesus to Saul: “Why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9:3-4) 4. Joan of Arc: The Church and Christ are “one thing” II. Ekklesia A. God created the world for communion with him (CCC, par. 760) B. Sin scatters; God gathers 1. God calls man into the unity of his family and household (CCC, par. 1) 2. God calls man out of the world C. The Church takes Christ’s life to the nations 1. Proclamation and evangelization (Lumen Gentium, 33) 2. Renewal of the temporal order (Apostolicam Actuositatem, 13) III. Four Marks of the Church A. One 1. The Church is one because God is One 2. The Church works to unite the world in God 3. The Church works to heal divisions (ecumenism) B. Holy 1. The Church is holy because her Head, Christ, is holy 2. The Church contains sinners, but is herself holy 3. The Church is made holy by God’s grace C. Catholic 1. Kata holos = “according to the whole” 2. The Church is the new Israel, universal 3. The Church transcends cultures, languages, nationalism Catholicism 1 D. Apostolic 1. From the lives, witness, and teachings of the apostles LESSON 6: THE MYSTICAL UNION OF CHRIST 2. -

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

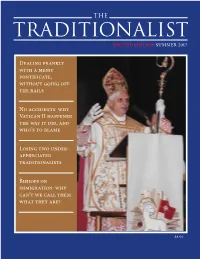

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8. -

Branson-Shaffer-Vatican-II.Pdf

Vatican II: The Radical Shift to Ecumenism Branson Shaffer History Faculty advisor: Kimberly Little The Catholic Church is the world’s oldest, most continuous organization in the world. But it has not lasted so long without changing and adapting to the times. One of the greatest examples of the Catholic Church’s adaptation to the modernization of society is through the Second Vatican Council, held from 11 October 1962 to 8 December 1965. In this gathering of church leaders, the Catholic Church attempted to shift into a new paradigm while still remaining orthodox in faith. It sought to bring the Church, along with the faithful, fully into the twentieth century while looking forward into the twenty-first. Out of the two billion Christians in the world, nearly half of those are Catholic.1 But, Vatican II affected not only the Catholic Church, but Christianity as a whole through the principles of ecumenism and unity. There are many reasons the council was called, both in terms of internal, Catholic needs and also in aiming to promote ecumenism among non-Catholics. There was also an unprecedented event that occurred in the vein of ecumenical beginnings: the invitation of preeminent non-Catholic theologians and leaders to observe the council proceedings. This event, giving outsiders an inside look at 1 World Religions (2005). The Association of Religious Data Archives, accessed 13 April 2014, http://www.thearda.com/QuickLists/QuickList_125.asp. CLA Journal 2 (2014) pp. 62-83 Vatican II 63 _____________________________________________________________ the Catholic Church’s way of meeting modern needs, allowed for more of a reaction from non-Catholics. -

Ave Papa Ave Papabile the Sacchetti Family, Their Art Patronage and Political Aspirations

FROM THE CENTRE FOR REFORMATION AND RENAISSANCE STUDIES Ave Papa Ave Papabile The Sacchetti Family, Their Art Patronage and Political Aspirations LILIAN H. ZIRPOLO In 1624 Pope Urban VIII appointed Marcello Sacchetti as depositary general and secret treasurer of the Apostolic Cham- ber, and Marcello’s brother, Giulio, bishop of Gravina. Urban later gave Marcello the lease on the alum mines of Tolfa and raised Giulio to the cardinalate. To assert their new power, the Sacchetti began commissioning works of art. Marcello discov- ered and promoted leading Baroque masters, such as Pietro da Cortona and Nicolas Poussin, while Giulio purchased works from previous generations. In the eighteenth century, Pope Benedict XIV bought the collection and housed it in Rome’s Capitoline Museum, where it is now a substantial portion of the museum’s collection. By focusing on the relationship between the artists in ser- vice and the Sacchetti, this study expands our knowledge of the artists and the complexity of the processes of agency in the fulfillment of commissions. In so doing, it underlines how the Sacchetti used art to proclaim a certain public image and to announce Cardinal Giulio’s candidacy to the papal throne. ______ copy(ies) Ave Papa Ave Papabile Payable by cheque (to Victoria University - CRRS) ISBN 978-0-7727-2028-2 or by Visa/Mastercard $24.50 Name as on card ___________________________________ (Outside Canada, please pay in US $.) Visa/Mastercard # _________________________________ Price includes applicable taxes. Expiry date _____________ Security code ______________ Send form with cheque/credit card Signature ________________________________________ information to: Publications, c/o CRRS Name ___________________________________________ 71 Queen’s Park Crescent East Address __________________________________________ Toronto, ON M5S 1K7 Canada __________________________________________ The Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies Victoria College in the University of Toronto Tel: 416-585-4465 Fax: 416-585-4430 [email protected] www.crrs.ca . -

The Attractiveness of the Tridentine Mass by Alfons Cardinal Stickler

The Attractiveness of the Tridentine Mass by Alfons Cardinal Stickler Cardinal Alfons Stickler, retired prefect of the Vatican Archives and Library, is normally reticent. Not so during his trip to the New York area in May [1995]. Speaking at a conference co-sponsored by Fr. John Perricon's ChistiFideles and Howard Walsh's Keep the Faith, the Cardinal scored Catholics within the fold who have undermined the Church—and in the final third of his speech made clear his view that the "Mass of the post-Conciliar liturgical commission" was a betrayal of the Council fathers. The robust 84-year-old Austrian scholar, a Salesian who served as peritus to four Vatican II commissions (including Liturgy), will celebrate his 60th anniversary as a priest in 1997. Among his many achievements: The Case for Clerical Celibacy (Ignatius Press), which documents that the celibate priesthood was mandated from the earliest days of the Church. Cardinal Stickler lives at the Vatican. The Tridentine Mass means the rite of the Mass which was fixed by Pope Pius V at the request of the Council of Trent and promulgated on December 5, 1570. This Missal contains the old Roman rite, from which various additions and alterations were removed. When it was promulgated, other rites were retained that had existed for at least 200 years. Therefore, is more correct to call this Missal the liturgy of Pope Pius V. Faith and Liturgy From the very beginning of the Church, faith and liturgy have been intimately connected. A clear proof of this can be found in the Council of Trent itself. -

PARTS of the TRIDENTINE MASS INTRODUCTORY RITES Priest And

PARTS OF THE TRIDENTINE MASS INTRODUCTORY RITES PRAYERS AT THE FOOT OF THE ALTAR Priest and ministers pray that God forgive his, and the people=s sins. KYRIE All ask the Lord to have mercy. GLORIA All praise the Glory of God. COLLECT Priest=s prayer about the theme of Today=s Mass. MASS OF CATECHUMENS EPISTLE New Testament reading by one of the Ministers. GRADUAL All praise God=s Word. GOSPEL Priest reads from one of the 4 Gospels SERMON The Priest now tells the people, in their language, what the Church wants them to understand from today=s readings, or explains a particular Church teaching/rule. CREED All profess their faith in the Trinity, the Catholic Church, baptism and resurrection of the dead. LITURGY OF THE EUCHARIST THE OFFERTORY The bread and wine are brought to the Altar and prepared for consecration. THE RITE OF CONSECRATION The Preface Today=s solemn intro to the Canon, followed by the Sanctus. The Canon The fixed prayers/actions for the consecration of the bread/wine. Before the Consecration The Church, gathered around the pope and in union with the saints, presents the offerings to God and prays that they are accepted to become the Body/Blood of Christ. The Consecration ΑThis is not a prayer: it is the recital of what took place at the Last Supper: the priest does again what the Lord did, speaks the Lord=s own words.≅ After the Consecration The Church offers Christ=s own sacrifice anew to God, to bring the Church together in peace, save those in Purgatory and Αus sinners≅ , so that Christ may give honor to the Father. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream.