Pdf, 649.7 Kb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Council, 31/07/08

Y CYNGOR 31/07/08 THE COUNCIL, 31/07/08 Present: Councillor Evie Morgan Jones (Chair) Councillor Anne Lloyd Jones (Vice-chair) Councillors: Bob Anderson, S W Churchman, Anwen Davies, E T Dogan, Dyfed Edwards, Dylan Edwards, Huw Edwards, Trevor Edwards, T G Ellis, Alan Jones Evans, Alun Wyn Evans, Jean Forsyth, K Greenly-Jones, Gwen Griffith, Margaret Griffith, Alwyn Gruffydd, Siân Gwenllian, Christopher Hughes, Dafydd Ll Hughes, Huw Price Hughes, Louise Hughes, O P Huws, Aeron M Jones, Brian Jones, Charles W Jones, Dai Rees Jones, Dyfrig Wynn Jones, Eric Merfyn Jones, John Gwilym Jones, J R Jones, John Wynn Jones, Linda Wyn Jones, R L Jones, Penri Jones, Eryl Jones-Williams, P.G.Larsen, Dewi Lewis, Dilwyn Lloyd, June Marshall, Keith Marshall, J W Meredith, Llinos Merks, Linda Morgan, Dewi Owen, W Roy Owen, W Tudor Owen, Arwel Pierce, Peter Read, Dafydd W Roberts, Caerwyn Roberts, Glyn Roberts, Gwilym Euros Roberts, John Pughe Roberts, Liz Saville Roberts, Siôn Selwyn Roberts, Trevor Roberts, W Gareth Roberts, Dyfrig Siencyn, Ann Williams, Gethin Glyn Williams, Gwilym Williams, J.W.Williams, Owain Williams, R H Wyn Williams and Robert J Wright. Also present: Harry Thomas (Chief Executive), Dilwyn Williams (Strategic Director - Resources), Dewi Rowlands (Strategic Director - Environment), Dafydd Edwards (Head of Finance), Dilys Phillips (Monitoring Officer/Head of Administration and Public Protection), Gareth Wyn Jones (Senior Legal and Administrative Manager), Arwel Ellis Jones (Senior Manager - Policy and Operational), Ann Owen (Policy and Performance Manager, Economy and Regeneration), Sharon Warnes (Senior Policy and Performance Manager - Development), Dylan Griffiths (Strategic and Financing Planning Manager), Eleri Parry (Senior Committee Manager) Invitees: Heulyn Davies, Senior Welsh Affairs Manager, Royal Mail Group Wales, Dave Wall, External Relations Manager, Post Office Ltd. -

Metacognition ‘An Introduction’

Metacognition ‘An Introduction’ 17 January 2019 Alex Quigley [email protected] @EducEndowFoundn 1 Task ‘Think-pair-share’ Describe the specific knowledge, skills, behaviours and traits of one of the most effective pupils in your school that you teach. @EducEndowFoundn @EducEndowFoundn Task How do people in the following high performing occupations think metacognitively in their daily work? @EducEndowFoundn Introducing the guidance… @EducEndowFoundn How did we create the guidance reports? @EducEndowFoundn EEF-Sutton Trust Teaching and Learning Toolkit How did we create the guidance reports? • Conversations with teachers, academics, providers • What is the interest in the issue? What are the misconceptions? Scoping • What is the gap between evidence and practice? • Kate Atkins (Rosendale), Alex Quigley (Huntington), David Whitebread (Cambridge), Steve Higgins (Durham) Jonathan Sharples (EEF and Advisory Panel UCL). Ellie Stringer • Undertaken by Daniel Muijs and Christian Bokhove (Southampton) • Systematic review of evidence and summarizing findings related to Evidence review questions we’re interested in (1300 research papers) • Daniel, Ellie and I draft and edit guidance Draft • Consult with Panel throughout guidance • Share draft with academics, teachers, Research Schools, developers mentioned. Consultation @EducEndowFoundn @EducEndowFoundn Dyw arweinydd Plaid Cymru, Leanne Wood, ddim wedi sicrhau cefnogaeth yr un o Aelodau Seneddol y blaid yn y ras am yr arweinyddiaeth, gyda'r rhan fwyaf yn cefnogi Adam Price i arwain y blaid. Ddydd Mawrth, fe gyhoeddodd Liz Saville Roberts a Hywel Williams eu bod yn ymuno â Jonathan Edwards, sydd hefyd yn cefnogi Mr Price. Gan fod Ben Lake yn cefnogi Rhun ap Iorwerth, mae'n golygu fod pedwar AS Plaid Cymru yn cefnogi newid yr arweinydd. -

Easy Read Manifesto Hires V3.Pages

Action Plan 2017 !1 Contents Page Defending Wales 3 Defending the things that are 5 important to Wales Protect the Welsh Assembly 6 Protecting Welsh jobs 7 A happier healthier Wales 8 Caring for those in need 9 Giving every child a chance 11 Connecting Wales 13 Protecting our communities 15 Energy and the environment 17 Country areas 19 Wales and the world 16 !2 Defending Wales There is a general election on Thursday June 8th. We get a chance to vote for Members of Parliament (MPs) to speak up for us in the UK Parliament in London. Plaid Cymru is the political party of Wales. This manifesto explains why it is important to vote for Plaid Cymru in this election. !3 Defending the things that are important to Wales The Tory Government is talking about how we leave the European Union (EU). They are breaking the links with the countries that we work with in Wales. This will make us poorer. Jobs will disappear. Wages are already going down and prices are going up. Labour are too busy fighting amongst themselves to stand up for Wales. Wales needs Plaid Cymru MPs to fight for the things that are important to Wales. !4 Plaid Cymru MPs will: Stand up for Wales and give us a • strong voice at this important time Fight to get the money promised • for our health services during the referendum campaign Protect the rights of hard working • European people who live and work in Wales Work to get the best Brexit deal for • Welsh industry and agriculture. -

Spice Briefing

MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY AND REGION Scottish SESSION 1 Parliament This Fact Sheet provides a list of all Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) who served during the first parliamentary session, Fact sheet 12 May 1999-31 March 2003, arranged alphabetically by the constituency or region that they represented. Each person in Scotland is represented by 8 MSPs – 1 constituency MSPs: Historical MSP and 7 regional MSPs. A region is a larger area which covers a Series number of constituencies. 30 March 2007 This Fact Sheet is divided into 2 parts. The first section, ‘MSPs by constituency’, lists the Scottish Parliament constituencies in alphabetical order with the MSP’s name, the party the MSP was elected to represent and the corresponding region. The second section, ‘MSPs by region’, lists the 8 political regions of Scotland in alphabetical order. It includes the name and party of the MSPs elected to represent each region. Abbreviations used: Con Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party Green Scottish Green Party Lab Scottish Labour LD Scottish Liberal Democrats SNP Scottish National Party SSP Scottish Socialist Party 1 MSPs BY CONSTITUENCY: SESSION 1 Constituency MSP Region Aberdeen Central Lewis Macdonald (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen North Elaine Thomson (Lab) North East Scotland Aberdeen South Nicol Stephen (LD) North East Scotland Airdrie and Shotts Karen Whitefield (Lab) Central Scotland Angus Andrew Welsh (SNP) North East Scotland Argyll and Bute George Lyon (LD) Highlands & Islands Ayr John Scott (Con)1 South of Scotland Ayr Ian -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

I Bitterly Regret the Day I Comgromised the Unity of My Party by Admitting

Scottish Government Yearbook 1990 FACTIONS, TENDENCIES AND CONSENSUS IN THE SNP IN THE 1980s James Mitchell I bitterly regret the day I comgromised the unity of my party by admitting the second member.< A work written over a decade ago maintained that there had been limited study of factional politics<2l. This is most certainly the case as far as the Scottish National Party is concerned. Indeed, little has been written on the party itself, with the plethora of books and articles which were published in the 1970s focussing on the National movement rather than the party. During the 1980s journalistic accounts tended to see debates and disagreements in the SNP along left-right lines. The recent history of the party provides an important case study of factional politics. The discussion highlights the position of the '79 Group, a left-wing grouping established in the summer of 1979 which was finally outlawed by the party (with all other organised factions) at party conference in 1982. The context of its emergence, its place within the SNP and the reaction it provoked are outlined. Discussion then follows of the reasons for the development of unity in the context of the foregoing discussion of tendencies and factions. Definitions of factions range from anthropological conceptions relating to attachment to a personality to conceptions of more ideologically based groupings within liberal democratic parties<3l. Rose drew a distinction between parliamentary party factions and tendencies. The former are consciously organised groupings with a membership based in Parliament and a measure of discipline and cohesion. The latter were identified as a stable set of attitudes rather than a group of politicians but not self-consciously organised<4l. -

1 Justice Committee Petition PE1370

Justice Committee Petition PE1370: Justice for Megrahi Written submission from Justice for Megrahi Ex-Scottish Government Ministers: Political Consequences of Public Statements On 28th June 2011 the Public Petitions Committee referred the Justice for Megrahi (JfM ) petition PE1370 to the Justice Committee for consideration. Its terms were as follows. ‘Calling on the Scottish Parliament to urge the Scottish Government to open an independent inquiry into the 2001 Kamp van Zeist conviction of Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi for the bombing of Pan Am flight 103 in December 1988.’ The petition was first heard by the Justice Committee on 8th November 2011. On 6th June, 2013, as part of its consideration, the Justice Committee wrote to Kenny MacAskill MSP, then Cabinet Secretary for Justice, asking for the Government’s comments on our request for a public enquiry. In his reply of 24th June 2013, while acknowledging, that under the Inquiries Act 2005, the Scottish Ministers had the power to establish an inquiry, he concluded: ‘Any conclusions reached by an inquiry would not have any effect on either upholding or overturning the conviction as it is appropriately a court of law that has this power. In addition to the matters noted above, we would also note that Lockerbie remains a live on-going criminal investigation. In light of the above, the Scottish Government has no plans to institute an independent inquiry into the conviction of Mr Al-Megrahi.’ At this time Alex Salmond was the First Minister and with Mr MacAskill was intimately involved in the release of Mr Megrahi on 20th August 2009, a decision which caused worldwide controversy. -

Theparliamentarian

100th year of publishing TheParliamentarian Journal of the Parliaments of the Commonwealth 2019 | Volume 100 | Issue Three | Price £14 The Commonwealth: Adding political value to global affairs in the 21st century PAGES 190-195 PLUS Emerging Security Issues Defending Media Putting Road Safety Building A ‘Future- for Parliamentarians Freedoms in the on the Commonwealth Ready’ Parliamentary and the impact on Commonwealth Agenda Workforce Democracy PAGE 222 PAGES 226-237 PAGE 242 PAGE 244 STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) exists to connect, develop, promote and support Parliamentarians and their staff to identify benchmarks of good governance, and implement the enduring values of the Commonwealth. 64th COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENTARY CONFERENCE Calendar of Forthcoming Events KAMPALA, UGANDA Confirmed as of 6 August 2019 22 to 29 SEPTEMBER 2019 (inclusive of arrival and departure dates) 2019 August For further information visit www.cpc2019.org and www.cpahq.org/cpahq/cpc2019 30 Aug to 5 Sept 50th CPA Africa Regional Conference, Zanzibar. CONFERENCE THEME: ‘ADAPTION, ENGAGEMENT AND EVOLUTION OF September PARLIAMENTS IN A RAPIDLY CHANGING COMMONWEALTH’. 19 to 20 September Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians (CWP) British Islands and Mediterranean Regional Conference, Jersey 22 to 29 September 64th Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference (CPC), Kampala, Uganda – including 37th CPA Small Branches Conference and 6th Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians (CWP) Conference. October 8 to 10 October 3rd Commonwealth Women Parliamentarians (CWP) Australia Regional Conference, South Australia. November 18 to 21 November 38th CPA Australia and Pacific Regional Conference, South Australia. November 2019 10th Commonwealth Youth Parliament, New Delhi, India - final dates to be confirmed. 2020 January 2020 25th Conference of the Speakers and Presiding Officers of the Commonwealth (CSPOC), Canada - final dates to be confirmed. -

Report of the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints

Published 23 March 2021 SP Paper 997 1st Report 2021 (Session 5) Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints Report of the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. All documents are available on the Scottish For information on the Scottish Parliament contact Parliament website at: Public Information on: http://www.parliament.scot/abouttheparliament/ Telephone: 0131 348 5000 91279.aspx Textphone: 0800 092 7100 Email: [email protected] © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliament Corporate Body The Scottish Parliament's copyright policy can be found on the website — www.parliament.scot Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints Report of the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints, 1st Report 2021 (Session 5) Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints To consider and report on the actions of the First Minister, Scottish Government officials and special advisers in dealing with complaints about Alex Salmond, former First Minister, considered under the Scottish Government’s “Handling of harassment complaints involving current or former ministers” procedure and actions in relation to the Scottish Ministerial Code. [email protected] Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints Report of the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints, 1st Report 2021 (Session 5) Committee -

The Brookings Institution

1 SCOTLAND-2013/04/09 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION SCOTLAND AS A GOOD GLOBAL CITIZEN: A DISCUSSION WITH FIRST MINISTER ALEX SALMOND Washington, D.C. Tuesday, April 9, 2013 PARTICIPANTS: Introduction: MARTIN INDYK Vice President and Director Foreign Policy The Brookings Institution Moderator: FIONA HILL Senior Fellow and Director Center on the United States and Europe The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: ALEX SALMOND First Minister of Scotland * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 2 SCOTLAND-2013/04/09 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. INDYK: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to Brookings. I'm Martin Indyk, the Director of the Foreign Policy Program at Brookings, and we're delighted to have you here for a special event hosted by Center on the U.S. and Europe at Brookings. In an historic referendum set for autumn of next year, the people of Scotland will vote to determine if Scotland should become an independent country. And that decision will carry with it potentially far-reaching economic, legal, political, and security consequences for the United Kingdom. Needless to say, the debate about Scottish independence will be watched closely in Washington as well. And so we are delighted to have the opportunity to host the Right Honorable Alex Salmond, the first Minister of Scotland, to speak about the Scottish independence. He has been First Minister since 2007. Before that, he has had a distinguished parliamentary career. He was elected member of the UK parliament in 1987, served there until 2010. -

Microsoft Outlook

From: LUCAS, Caroline Sent: 03 June 2021 10:36 To: Cc: Subject: RE: Correspondence from the Chair of the Procedure Committee Dear Karen, Thank you for your letter of 25th May, in response to the concerns we raised about accountability. We wanted to specifically follow up on the example you cite of Members’ capacity to bring substantive motions criticising the conduct of Ministers – you gave an example from June 2012 to illustrate. We do not deny that this mechanism exists, rather we wish to reiterate one of the points in our initial email, namely that such routes have limited impact when the government of the day has a substantial majority. As you will no doubt be aware, the example referenced led to a vote, and the motion was defeated 290 votes to 252. We consider that the influence of the Whips further renders such mechanisms unlikely to either result in objective consideration of the facts or to stand any significant chance of delivering genuine accountability. Some of us were involved in the lengthy process of drawing up the Independent Complaints and Grievance Scheme and recall the levels of opposition to change and to finding ways of preventing MPs marking their own homework with regards responsibility for bullying, harassment and sexual harassment. We would assert that the same principles apply in relation to lying - and that, similarly, public opinion is in favour of Parliament doing the right thing and leading by example. It’s welcome to hear that you will be looking at the Scottish system for correcting errors on the record, with a view to potentially introducing some improvements. -

Survey Report

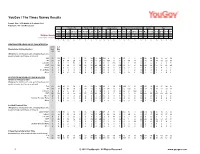

YouGov / The Times Survey Results Sample Size: 1100 Adults in Scotland (16+) Fieldwork: 4th - 8th March 2021 Vote in 2019 EU Ref 2016 Indy Ref Voting intention Holyrood Voting intention Gender Age Total Con Lab Lib Dem SNP Remain Leave Yes No Con Lab Lib Dem SNP Con Lab Lib Dem SNP Male Female 18-24 25-49 50-64 65+ Weighted Sample 1100 205 152 78 366 568 283 415 514 176 145 42 418 182 145 52 438 529 571 143 435 274 249 Unweighted Sample 1100 226 157 82 416 602 277 395 504 191 143 47 434 199 148 54 456 522 578 145 433 287 235 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % WESTMINSTER HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION 6-10 4-8 Westminster Voting Intention Nov Mar '20 '21 [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Con 19 23 84 7 8 1 17 40 4 40 100 0 0 0 93 6 3 0 25 20 12 16 27 32 Lab 17 17 5 64 20 5 19 16 8 27 0 100 0 0 3 88 11 2 16 18 18 15 20 19 Lib Dem 4 5 1 4 52 1 5 5 2 8 0 0 100 0 2 1 78 1 4 6 3 6 4 5 SNP 53 50 3 18 17 90 56 32 83 20 0 0 0 100 0 2 4 95 48 52 57 57 46 40 Green 3 3 0 6 3 2 3 0 1 2 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 3 3 6 4 1 2 Brexit Party 3 1 5 1 0 0 1 4 2 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 3 0 0 2 2 1 Other 1 1 2 0 0 0 0 2 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 3 1 0 1 HOLYROOD HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION Holyrood Voting Intention [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Con 19 22 80 6 18 1 18 38 4 39 93 3 10 0 100 0 0 0 25 19 13 17 24 31 Lab 15 17 10 59 15 4 17 18 8 26 5 87 4 1 0 100 0 0 17 16 14 14 20 18 Lib Dem 6 6 2 6 47 1 5 6 1 10 1 3 78 0 0 0 100 0 5 7 4 5 8 6 SNP 56 52 3