The Free University of New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Russell Tribunal in Stockholm 50 Years Ago - Seen with the CIA's Eyes

REPORTAGE The Russell Tribunal in Stockholm 50 years ago - seen with the CIA's eyes Jean-Paul Sartre in the presidium, on his right Vladimir Dedijer and Laurent Schwarz. PHOTO Joy Benigh 2017-06-30 Archives from the CIA, the US intelligence service, recently made available, provide a picture of the Russell Tribunal, held in Stockholm in 1967 in protest against the US war in Vietnam. The documents also highlight the spy organization's detailed information collection. 50 years ago, Stockholm became the center of building international opinion against the United States war in Vietnam. In 1967 there were two important meetings in Stockholm: the Russell Tribunal in May and the World Conference on Vietnam in July. Both concerned the fight against war crimes and have left their track on today´s political activities. The Russell Tribunal was more anti-imperialist and constituted a breakthrough in the world's opposition to the war. It became a pattern for similar tribunals in the future. The nine-year-old boy DoVan Ngoc exhibits terrible abdominal injuries caused by napalm bombs. Bending over the is boy Dr John Takman. The archives are opened slightly Since 2010, some of the archives of the CIA have been open to researchers. However, access has been limited to four data screens at the Maryland National Archives, which are open 5 working days a week between 9am and 4:30 pm. The stamp of secrecy has been removed on some part of more than 940,000 documents. These range from the 1940s to the 1990s, ie at least 25 years back. -

The Media and the 1967 International War Crimes Tribunal Sean Raming

We Shall Not Alter It Much By Our Words: The Media and the 1967 International War Crimes Tribunal Sean Raming To cite this version: Sean Raming. We Shall Not Alter It Much By Our Words: The Media and the 1967 International War Crimes Tribunal. Humanities and Social Sciences. 2020. dumas-02904655 HAL Id: dumas-02904655 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02904655 Submitted on 22 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. We Shall Not Alter It Much By Our Words The Media and the 1967 International War Crimes Tribunal Times Herald (Port Huron, MI). May 7, 1967. 8 Nom : Raming Prénom : Sean UFR : langues étrangères Mémoire de master 2 recherche - 30 crédits - Très Bien Spécialité ou Parcours : Études Anglophones LLCER Sous la direction de Michael S. Foley Année Universitaire 2019 - 2020 2 Déclaration anti-plagiat D en scann r U N I V E R S I T E,. ocum t à e e à t e u e oire eïcctr o ru ·q ue -- t- _ _in_ _é_gr_ r_ _a _m_ ·_ m_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Cr en Ob I e------ _ _ _ Alpes DECLARATION 1. -

Vote Democracy!

ENGAGING STUDENTS AND TEACHERS THROUGH FILM COMMUNITY CLASSROOM: VOTE DEMOCRACY! EDUCATOR GUIDE Educators can use the VOTE DEMOCRACY! Educator Guide to support viewing of PLEASE VOTE FOR ME, IRON LADIES OF LIBERIA, CHICAGO 10 and AN UNREASONABLE MAN while engaging students in discussions about democracy abroad, elections, third-party politics, gender, the role of dissent in democracy and media literacy. These lessons and activities also provide a con- text for understanding and further investigating the changing nature of democracy around the world. WWW.PBS.ORG/INDEPENDENTLENS/CLASSROOM COMMUNITYITVS CLASSROOM CLASSROOM VOTE DEMOCRACY! TABLE OF CONTENTS How To Use the Films and This Guide 3 About the Films 6 Activity 1: What is Democracy? 8 Activity 2: Third Party Voices 11 Activity 3: Participating in a Campaign 14 Activity 4: Democracy Around the World 17 Activity 5: Women and Democracy 20 Activity 6: Dissent in Democracy 24 Activity 7: Media Literacy 28 Student Handouts 31 Teacher Handouts 34 National Standards 42 Guide Credits 43 COMMUNITY CLASSROOM is an exciting resource for educators. It provides short video modules drawn from the Emmy® Award–winning PBS series Independent Lens. Drawn from the United States and abroad, these stories reflect the diversity of our world through the lens of contemporary documentary filmmakers. The COMMUNITY CLASSROOM video modules are supported with innovative, resource-rich curricula for high school, college and other youth educators. The video modules are five to ten minutes in length and can be viewed online or on DVD. Content is grouped into subject-specific segments corresponding to lesson plans and is standards- based. -

Joe Matheny, a Founding Father Culture Jammer, Was Kind Enough to Give What He Called His "Last Interview" Online to Escape

9/11/2014 escape.htm Joe Matheny, a founding father Culture Jammer, was kind enough to give what he called his "last interview" online to Escape. Now happily working towards his pension in an anonymous programmer's job, Joe famously spammed the White House with a bunch of email frogs and caused uproar in American media society with his many japes. But why did it get all serious? And why are none of the original CJers talking to each other? What follows is the unedited version of the interview published in December 1997's Escape. All the hotlinks are Joe's. So who started Culture Jamming as a phenomenon, and why? Boy, that's a loaded question! No, really. It depends on who you ask. Personally I trace the roots of media pranking, or "culture jamming" as it's known these days, to people like Orson Welles and his famous "War of the Worlds" broadcast in America, or even his lesser known film "F is for Fake". More recently, a scientist by the name of Harold Garfinkle conducted something called breaching experiments, in which he studied the flexbility of peoples belief systems by fabricating stories and then guaging peoples reaction to them.He called this field of study Ethnomethodology and popularized it in his book Studies in Ethnomethodology. Garfinkle would incrementally make the his stories wilder and more speculative until the subjects would finally reach a point of disbelief. (in other words Garfinkle perpetrated lies, and then "pushed the envelope" with his subjects) In the 60s CJ was taken to a whole new level by two very differnet groups. -

Intellectuals In

Intellectuals in The Origins of the New Left and Radical Liberalism, 1945 –1970 KEVIN MATTSON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mattson, Kevin, 1966– Intellectuals in action : the origins of the new left and radical liberalism, 1945–1970 / Kevin Mattson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-271-02148-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-271-02206-X (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. New Left—United States. 2. Radicalism—United States. 3. Intellectuals— United States—Political activity. 4. United States and government—1945–1989. I. Title. HN90.R3 M368 2002 320.51Ј3Ј092273—dc21 2001055298 Copyright ᭧ 2002 The Pennsylvania State University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA 16802–1003 It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper for the first printing of all clothbound books. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. For Vicky—and making a family together In my own thinking and writing I have deliberately allowed certain implicit values which I hold to remain, because even though they are quite unrealizable in the immediate future, they still seem to me worth displaying. One just has to wait, as others before one have, while remembering that what in one decade is utopian may in the next be implementable. —C. Wright Mills, “Commentary on Our Country, Our Culture,” 1952 Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Why Go Back? 1 1 A Preface to the politics of Intellectual Life in Postwar America: The Possibility of New Left Beginnings 23 2 The Godfather, C. -

Page 1 of 279 FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS

FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS. January 01, 2012 to Date 2019/06/19 TITLE / EDITION OR ISSUE / AUTHOR OR EDITOR ACTION RULE MEETING (Titles beginning with "A", "An", or "The" will be listed according to the (Rejected / AUTH. DATE second/next word in title.) Approved) (Rejectio (YYYY/MM/DD) ns) 10 DAI THOU TUONG TRUNG QUAC. BY DONG VAN. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 DAI VAN HAO TRUNG QUOC. PUBLISHER NHA XUAT BAN VAN HOC. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 POWER REPORTS. SUPPLEMENT TO MEN'S HEALTH REJECTED 3IJ 2013/03/28 10 WORST PSYCHOPATHS: THE MOST DEPRAVED KILLERS IN HISTORY. BY VICTOR REJECTED 3M 2017/06/01 MCQUEEN. 100 + YEARS OF CASE LAW PROVIDING RIGHTS TO TRAVEL ON ROADS WITHOUT A APPROVED 2018/08/09 LICENSE. 100 AMAZING FACTS ABOUT THE NEGRO. BY J. A. ROGERS. APPROVED 2015/10/14 100 BEST SOLITAIRE GAMES. BY SLOANE LEE, ETAL REJECTED 3M 2013/07/17 100 CARD GAMES FOR ALL THE FAMILY. BY JEREMY HARWOOD. REJECTED 3M 2016/06/22 100 COOL MUSHROOMS. BY MICHAEL KUO & ANDY METHVEN. REJECTED 3C 2019/02/06 100 DEADLY SKILLS SURVIVAL EDITION. BY CLINT EVERSON, NAVEL SEAL, RET. REJECTED 3M 2018/09/12 100 HOT AND SEXY STORIES. BY ANTONIA ALLUPATO. © 2012. APPROVED 2014/12/17 100 HOT SEX POSITIONS. BY TRACEY COX. REJECTED 3I 3J 2014/12/17 100 MOST INFAMOUS CRIMINALS. BY JO DURDEN SMITH. APPROVED 2019/01/09 100 NO- EQUIPMENT WORKOUTS. BY NEILA REY. REJECTED 3M 2018/03/21 100 WAYS TO WIN A TEN-SPOT. BY PAUL ZENON REJECTED 3E, 3M 2015/09/09 1000 BIKER TATTOOS. -

Influencer Marketing Class

WELCOME TO CAMPUS NEW YORK ! 1 UNIVERSIDAD ADOLFO IBANEZ & EFAP NEW YORK- NYIT 1855 Broadway, New York, NY 10023-USA PROGRAM DESCRIPTION § 15 Hours Lecture § 15 hours Conference,Professional meet up, company visits and workshop § 10 hours Cultural visits DATES § From July 19th to Friday 31st 2020 2 TENTATIVE SCHEDULE Week 1 Week 2 Morning Afternoon Morning Afternoon Pick –up & Sunday 19/7 Check in Transfer to Free Free hotel Welcome and Influencer Central Park Monday campus tour- Wall Street Marketing Visit Workshop class Conference & Influencer Tuesday Professional free Marketing Company visit meet up class Conference & Influencer Influencer Wednesday Professional Harlem Marketing Marketing meet up class class Conference & Influencer Company visit Professional Thursday free Marketing + meet up class Farewell diner Conference & Grand Check out Friday Professional Central 31/7 meet up Optional activity : 9/11 Saturday Museum with Memorial Tour - - 3 - Statue of Liberty CAMPUS ADDRESS: 1855 Broadway, New York, NY 10023-USA 4 Week 1: Conference & Professional Meet up/ Workshop Workshop: Narrative Storytelling -Exploration of how descriptive language advance a story in different art forms Conference & Professional Meet up The New Digital Marketing Trends – Benjamin Lord, Executive Director Global e-Commerce NARS at Shisheido Group (Expert in brand management, consumer technology and digital marketing at a global level) Conference & Professional Meet up Evolution of the Social Media Landscape and how to reinforce the social media engagement? Colin Dennison – Digital Communication Specialist at La Guardia Gateway Partners Conference & Professional Meet up From business intelligence to artificial intelligence: How the artificial intelligence will predict customer behavior – Xavier Degryse – President & Founder MX-Data (Leader in providing retail IT services to high profile customers in the luxury and fashion industries . -

The Hidden History of Zionism by Ralph Schoenman

The Hidden History of Zionism by Ralph Schoenman Bibliographic Note The Hidden History of Zionism By Ralph Schoenman Copyright (c) 1988 by Ralph Schoenman All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 88-50585 ISBN: 0-929675-00-2 (Hardcover) ISBN: 0-929675-01-0 (Paperback) Manufactured in the United States First Edition, 1988 Veritas Press PO BOX 6090 Vallejo CA 94591 Cover design by Mya Shone Cover photograph by Donald McCullin (As printed in The Palestinians by Jonathan Dimbleby, Quartet Books, Ltd.) Copies of the printed edition of The Hidden History of Zionism, in hardcover or paperback form, can be purchased either directly from Veritas Press (in the above address), or purchased online here on this blog. Most of this online edition of The Hidden History of Zionism was transcribed from the 1988 Veritas Press edition by Alphonsos Pangas in 2000, by permission of the author, and originally published in the Balkan Unity site. This on-line edition was copied from the Balkan Unity site and is also posted here in Reds Die Rotten site. Some chapters were added to complete the book by Einde O'Callaghan. It goes without saying that the permission to publish this work doesn’t imply that the author is in agreement with the content of the REDS – Die Roten site. The Hidden History of Zionism by Ralph Schoenman is presented online for personal use only. No portions of this book may be reprinted, reposted or published without written permission from the author. i About the Author Ralph Schoenman was Executive Director of the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation, in which capacity he conducted negotiations with numerous heads of state. -

To View Proposal

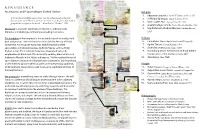

R E N A I S S A N C E Architecture and Placemaking in Central Harlem Religion 1. Abyssinian Baptist: Charles W. Bolton & Son, 1923 It is true the formidable centers of our race life, educational, industrial, 2. St Philip's Episcopal: Tandy & Foster, 1911 financial, are not in Harlem, yet here, nevertheless are the forces that make a 3. Mother AME Zion: George Foster Jr, 1925 group known and felt in the world. —Alain Locke, “Harlem” 1925 4. Greater Refuge Temple: Costas Machlouzarides, 1968 We intend to study the landmarks in Harlem to understand the 5. Majid Malcolm Shabazz Mosque: Sabbath Brown, triumphs and challenges of Black placemaking in America. 1965 The backdrop to this proposal is the national story of inequality, both Culture past and present. Harlem’s transformation into the Mecca of Black 6. Paris Blues: Owned by the late Samuel Hargress Jr. culture that we recognize today was enabled by failed white 7. Apollo Theater: George Keister, 1914 speculation and shrewd business by Black figures such as Philip 8. Studio Museum: David Adjaye, 2021 Payton Junior. The Harlem Renaissance blossomed out of the 9. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture: neighborhood’s Black and African identity, enabling Black artists and Charles McKim, 1905; Marble Fairbanks, 2017 thinkers to flourish in the 1920s and beyond. Yet, the cyclical forces of 10. Showman’s Jazz Club speculation, rezoning and rising land values undermine this flourishing and threaten to uproot Harlem’s poorer and mostly Black population, People while landmark designations seek to preserve significant portions of 11. -

Reflections on Progressive Media Since 1968

THIRD WORLD NEWSREEL Reflections on Progressive Media Since 1968 CREDITS 2008 Editor: Cynthia Young 2018 Editors: Luna Olavarría Gallegos, Eric Bilach, Elizabeth Escobar and Andrew James Cover Design: Andrew James Layout Design: Luna Olavarría Gallegos Cover Photo: El Pueblo Se Levanta, Newsreel, 1971 THIRD WORLD NEWSREEL BOARD OF DIRECTORS Dorothy Thigpen (former TWN Executive Director) Sy Burgess Afua Kafi Akua Betty Yu Joel Katz (emeritus) Angel Shaw (emeritus) William Sloan (eternal) The work of Third World Newsreel is made possible in part with the support of: The National Endowment for the Arts The New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the NY State Legislature Public funds from the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council The Peace Development Fund Individual donors and committed volunteers and friends TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. TWN Fifty Years..........................................................................4 JT Takagi, 2018 2. Foreword....................................................................................7 Luna Olavarría Gallegos, 2015 3. Introduction................................................................................9 Cynthia Young, 1998 NEWSREEL 4. On Radical Newsreel................................................................12 Jonas Mekas, c. 1968 5. Newsreel: A Report..................................................................14 Leo Braudy, 1969 6. Newsreel on Newsreel.............................................................19 -

Scoping out the International Spy Museum

Acad. Quest. DOI 10.1007/s12129-010-9171-1 ARTICLE Scoping Out the International Spy Museum Ronald Radosh # The Authors 2010 The International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C.—a private museum that opened in July 2002 at the cost of $40 million—is rated as one of the most visited and popular tourist destinations in our nation’s capital, despite stiff competition from the various public museums that are part of the Smithsonian. The popularity of the Spy Museum has a great deal to do with how espionage has been portrayed in the popular culture, especially in the movies. Indeed, the museum pays homage to cinema with its display of the first Aston Martin used by James Bond, when Agent 007 was played by Sean Connery in the films made during the JFK years. The Spy Museum’s board of directors includes Peter Earnest, a former CIA operative and the museum’s first chief executive; David Kahn, the analyst of cryptology; Gen. Oleg Kalugin, a former KGB agent; as well as R. James Woolsey, a former director of the CIA. Clearly, the board intends that in addition to the museum’s considerable entertainment value, its exhibits and texts convey a sense of the reality of the spy’s life and the historical context in which espionage agents operated. The day I toured the museum it was filled with high school students who stood at the various exhibits taking copious notes. It was obvious that before their visit the students had been told to see what the exhibits could teach them about topics discussed in either their history or social studies classes. -

Arne Swabeck Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4s2012z6 No online items Register of the Arne Swabeck papers Finding aid prepared by David Jacobs Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 2003 Register of the Arne Swabeck 87019 1 papers Title: Arne Swabeck papers Date (inclusive): 1913-1999 Collection Number: 87019 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 21 manuscript boxes(8.4 linear feet) Abstract: Memoirs, other writings, correspondence, resolutions, bulletins, minutes, pamphlets, and serial issues, relating to socialist and communist movements in the United States, and especially to the Socialist Workers Party and other Trotskyist groups in the post-World War II period. Creator: Swabeck, Arne Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Arne Swabeck papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1987. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at https://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number