Copyright by Kayti Adaire Lausch 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

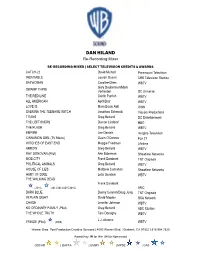

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer RE-RECORDING MIXER | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS & AWARDS CATCH-22 David Michod Paramount Television INSATIABLE Lauren Gussis CBS Television Studios BATWOMAN Caroline Dries WBTV Gary Dauberman/Mark SWAMP THING Verheiden DC Universe THE RED LINE Cairlin Parrish WBTV ALL AMERICAN April Blair WBTV LOVE IS Mara Brock Akil OWN SABRINA THE TEENAGE WITCH Jonathan Schmock Viacom Productions TITANS Greg Berlanti DC Entertainment THE LEFTOVERS Damon Lindelof HBO THE FLASH Greg Berlanti WBTV EMPIRE Lee Daniels Imagine Television CINNAMON GIRL (TV Movie) Gavin O'Connor Fox 21 WITCHES OF EAST END Maggie Friedman Lifetime ARROW Greg Berlanti WBTV RAY DONOVAN (Pilot) Ann Biderman Showtime Networks MOB CITY Frank Darabont TNT Originals POLITICAL ANIMALS Greg Berlanti WBTV HOUSE OF LIES Matthew Carnahan Showtime Networks HART OF DIXIE Leila Gerstein WBTV THE WALKING DEAD Frank Darabont (2010) (2012/2014/2015/2016) AMC DARK BLUE Danny Cannon/Doug Jung TNT Originals IN PLAIN SIGHT David Maples USA Network CHASE Jennifer Johnson WBTV NO ORDINARY FAMILY (Pilot) Greg Berlanti ABC Studios THE WHOLE TRUTH Tom Donaghy WBTV J.J. Abrams FRINGE (Pilot) (2009) WBTV Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.7825 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS LIMELIGHT (Pilot) David Semel, WBTV HUMAN TARGET Jonathan E. Steinberg WBTV EASTWICK Maggie Friedman WBTV V (Pilot) Kenneth Johnson WBTV TERMINATOR: THE SARAH CONNER Josh Friedman CHRONICLES WBTV CAPTAIN -

Pg TV Guide 2.Indd

SUNDAY EVENING A-DirecTV;B-Dish;C-Brandenburg MAY 6, 2012 A B C 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 TV Guide Listings 3/WAVE 3 3 3Dateline NBC (N) Harry’s Law (N) The Celebrity Apprentice (N) Å WAVE 3 News Extra (N) 7/WTVW News Home Offi ce Theory Theory News House (S) Å McCarv 9/WNIN Jubilee (S) Å Finding-Roots Masterpiece Mystery! (S) Great Performances at the Met Å 11/WHAS 11 11 11 Funny Videos Upon a Time Desp.-Wives (:01) GCB Å News Criminal Minds (S) May 2 - May 8 23/WKZT 4Manor Summer Time/By Served? Masterpiece Mystery! (S) Land Globe Trekker (S) Religion 32/WLKY 32 32 560 Minutes Å The Amazing Race (S) Å NYC 22 (N) Å News News Access 34/WBKI 34 34 17 Fturama Fturama ››› “Chicago” (2002, Musical) News Insider (:05) TMZ (N) (S) Electric SATURDAY MORNING A-DirecTV;B-Dish;C-Brandenburg MAY 5, 2012 41/WDRB 41 41 12 Simpson Cleve Simpson Burgers Family Amer. News Sports Theory Two 30 Rock A B C 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 A&E 265 118 79 Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Storage Duck D. Duck D. Duck D. Duck D. Storage Frozen Planet (S) River Monsters Swamp Wars (N) River Monsters (S) Swamp Wars (S) Monster 3/WAVE 3 3 3Today (N) (S) Å Wave 3’s Derby Day ANPLAN 282 184 78 CNN 202 200 24 CNN Newsroom CNN Presents Piers Morgan CNN Newsroom CNN Presents Piers 7/WTVW Paid Paid Garden Wild Busi Home. -

WORST COOKS in AMERICA: CELEBRITY EDITION Contestant Bios

Press Contact: Lauren Sklar Phone: 646-336-3745; Email: [email protected] WORST COOKS IN AMERICA: CELEBRITY EDITION Contestant Bios MINDY COHN Mindy Cohn made her acting debut as the witty, precious Eastland Academy student Natalie Green in the hit comedy series The Facts of Life. She was discovered while attending Westlake School for Girls in Bel Air, California, when actress Charlotte Rae and producer Norman Lear came to the school to authenticate scripts for their new show. Ms. Rae was so taken with the vivacious eighth grader she convinced producers to create a role for her. Mindy remained on the show for all nine seasons, also traveling to Paris and Australia with her co-stars to produce two successful television movies based on the series. Concurrently, with her role in Facts, Mindy played “Rose Jenko” in Fox’s 21 Jump Street. Other notable television appearances included Diff’rent Strokes, Double Trouble, Charles in Charge, Dream On and Suddenly Susan. In 1983, Mindy appeared in her first professional stage performance in Table Settings, written and directed by James Lapine and filmed for HBO Television. The illustrious cast included Eileen Heckart, Stockard Channing, Robert Klein, Peter Riegart, and Dinah Manoff. She went on to make her feature film debut in The Boy Who Could Fly, which co-starred Colleen Dewhurst, Fred Gwynne and Fred Savage. Mindy took a hiatus from her career to attend university, where she earned a Bachelor’s degree in Cultural Anthropology and a Masters in Education. During this time, she studied improvisation and scene work with Gary Austin and Larry Moss. -

Florida International University Magazine Fall 2006 Florida International University Division of University Relations

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Magazine Special Collections and University Archives Fall 2006 Florida International University Magazine Fall 2006 Florida International University Division of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/fiu_magazine Recommended Citation Florida International University Division of University Relations, "Florida International University Magazine Fall 2006" (2006). FIU Magazine. 4. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/fiu_magazine/4 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and University Archives at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Magazine by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE FALL 2006 20/20 VISION President Modesto A. Maidique crowns his 20-year anniversary at FIU with an historic accomplishment, winning approval for a new College of Medicine. Also in this issue: Alumna Dawn Ostroff ’80 FIU honors alumni College of Business takes the helm of a at largest-ever Administration expansion new television network Torch Awards Gala garners support THE 2006 GOLDEN PANTHERS FOOTBALL SEASON WILL BE THE HOTTEST ON RECORD WITH THE HISTORIC FIRST MATCHUP AGAINST THE UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI AT THE ORANGE BOWL. DON'T MISS A MOMENT, CALL FOR YOUR TICKETS TODAY: 1 -866-FIU-GAME FIU Golden Panthers 2006 Season Aug Middle Tennessee A 7 p.m. September 9* South Florida A 7 p.m. Raymond James Stadium, Tampa September 16* Bowling green H 6 p.m. Sept * Maryland Arkansas State Parents weekend North Texas University of Miami A TBA Orange Bowl, Miami October .21 Alabama A TBA INfoverrtber Louisiana-Monroe H 7 p.m. -

Snowschool Offered to Local Students Environment

6 TUESDAY, JANUARY 28, 2020 The Inyo Register SnowSchool offered to local students environment. The second with water. The food color- journey is unique. This Bishop, session allows students to ing and glitter represent game shows students how Mammoth review the first lesson and different, pollutants that water moves through the learn how to calculate snow might enter the watershed, earth, oceans, and atmo- Lakes fifth- water equivalent. The final and students can observe sphere, and gives them a grade students session takes students how the pollutants move better understanding of from the classroom to the and collect in different the water cycle. participate in mountains for a SnowSchool bodies of water. For the final in-class field day. Once firmly in For the second in-class activity, students learn SnowSchool snowshoes, the students activity, students focus on about winter ecology and learn about snow science the water cycle by taking how animals adapt for the By John Kelly hands-on and get a chance on the role of a water mol- winter. Using Play-Doh, Education Manager, ESIA to play in the snow. ecule and experiencing its they create fictional ani- During the in-class ses- journey firsthand. Students mals that have their own For the last five years, sion, students participate break up into different sta- winter adaptations. Some the Eastern Sierra in three activities relating tions. Each station repre- creations in past Interpretive Association to watersheds, the water sents a destination a water SnowSchools had skis for (ESIA) and Friends of the cycle, and winter ecology. molecule might end up, feet to move more easily Inyo have provided instruc- In the first activity, stu- such as a lake, river, cloud, on the snow and shovels tors who deliver the Winter dents create their own glacier, ocean, in the for hands for better bur- Wildlands Alliance’s watershed, using tables groundwater, on the soil rowing ability. -

This Is a Test

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Pam Slay, 818-755-2480 October 3, 2012 [email protected] HALLMARK CHANNEL DELIVERS ‘THE HEART OF CHRISTMAS’ HERE COMES THE CHRISTMAS BRIDE! ARIELLE KEBBEL AND ANDREW WALKER STAR IN ‘A BRIDE FOR CHRISTMAS,’ A HALLMARK CHANNEL ORIGINAL MOVIE WORLD PREMIERE, DECEMBER 1 “A Bride for Christmas” Is Rated: J For Joy, F For Family And P For Presents* #Bride4Christmas Arielle Kebbel (“90210” “Life Unexpected”) is a three-time bride-to-be who calls off her engagement right before the holidays when she stars in “A Bride for Christmas,” a Hallmark Channel Original Movie World Premiere Saturday, December 1 (8p.m. ET/PT, 7C). Kebbel stars as Jessie who is closed off to love due to her many failed engagements, but might just find some Christmas romance with Andrew Walker (“Against the Wall”), who co-stars as her hopeful suitor. After Jessie Patterson (Kebbel) calls off her third engagement - at the altar! - she swears off serious relationships until she finds “the one.” That is, until charming but chronically single Aiden MacTiernan (Walker) comes along. Unbeknownst to Jessie, Aiden has bet his friends that he can convince a woman to marry him by Christmas - which is only four weeks away - and Jessie is the target of his bet. As Aiden attempts to court Jessie by first hiring her to decorate his apartment, Jessie looks to her sister, roommate and interior design company partner, Vivian (Kimberly Sustad, “Alcatraz”) as her closest confidant. Vivian advises her to keep it professional with Aiden. To complicate matters, Jessie is doggedly pursued by her most recent ex-fiancé, Mike (Sage Brocklebank, “Psych”), who still wants to marry her. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

'The Mystery Cruise' Cast Bios Gail O'grady

‘THE MYSTERY CRUISE’ CAST BIOS GAIL O’GRADY (Alvirah Meehan) – Multiple Emmy® nominee Gail O'Grady has starred in every genre of entertainment, including feature films, television movies, miniseries and series television. Her most recent television credits include the CW series “Hellcats” as well as "Desperate Housewives" as a married woman having an affair with the teenaged son of Felicity Huffman's character. On "Boston Legal," her multi-episode arc as the sexy and beautiful Judge Gloria Weldon, James Spader's love interest and sometime nemesis, garnered much praise. Starring series roles include the Kevin Williamson/CW drama series "Hidden Palms," which starred O'Grady as Karen Miller, a woman tormented by guilt over her first husband's suicide and her son's subsequent turn to alcohol. Prior to that, she starred as Helen Pryor in the critically acclaimed NBC series "American Dreams." But O'Grady will always be remembered as the warm-hearted secretary Donna Abandando on the series "NYPD Blue," for which she received three Emmy Award nominations for Best Supporting Actress in a Dramatic Series. O'Grady has made guest appearances on some of television's most acclaimed series, including "Cheers," "Designing Women," "Ally McBeal" and "China Beach." She has also appeared in numerous television movies and miniseries including Hallmark Channel's "All I Want for Christmas" and “After the Fall” and Lifetime's "While Children Sleep" and "Sex and the Single Mom," which was so highly rated that it spawned a sequel in which she also starred. Other television credits include “Major Crimes,” “Castle,” “Hawaii Five-0,” “Necessary Roughness,” “Drop Dead Diva,” “Ghost Whisperer,” “Law & Order: SVU,” “CSI: Miami,” "The Mentalist," "Vegas," "CSI," "Two and a Half Men," "Monk," "Two of Hearts," "Nothing Lasts Forever" and "Billionaire Boys Club." In the feature film arena, O'Grady has worked with some of the industry's most respected directors, including John Landis, John Hughes and Carl Reiner and has starred with several acting legends. -

WHAM Buys Local Channel

Report Information from ProQuest March 01 2014 11:31 Table of contents 1. WHAM buys local channel Bibliography Document 1 of 1 WHAM buys local channel Author: Chao, Mary ProQuest document link Abstract: Mary Chao Staff writer The parent company of WHAM-TV (Channel 13) has acquired the local CW affiliate, which airs shows such as Girlfriends, Everybody Hates Chris, Smallville and Gilmore Girls. Full text: Mary Chao Staff writer The parent company of WHAM-TV (Channel 13) has acquired the local CW affiliate, which airs shows such as Girlfriends, Everybody Hates Chris, Smallville and Gilmore Girls. The CW affiliate, WRWB (cable Channel 16), had been a joint venture of Time Warner Cable and Warner Brothers. Now it will be operated by Clear Channel Television's WHAM and will be renamed CW-WHAM, said Chuck Samuels, vice president and general manager of Channel 13, who will head both stations. Terms of the deal were not disclosed. The CW was created when Warner Brothers merged with UPN, taking the "C" from CBS, which owned UPN, and the "W" from Warner. The Rochester station will remain on cable Channel 16 and will also be available as WHAM-DT on digital channel 13.2. Samuels said the station will complement Channel 13. "The CW has a very different target audience," he said. "While most networks such as ABC target (ages) 18 to 49, the CW targets 18 to 34, even 12 to 34." The CW will help WHAM's already established news brand by reaching out to younger audiences, Samuels said. WRWB's operations in downtown Rochester will be consolidated into WHAM's facilities in Henrietta. -

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation Yueqin Yang, M.A. Mentor: Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D. This thesis commits to highlighting major stereotypes concerning Asians and Asian Americans found in the U.S. media, the “Yellow Peril,” the perpetual foreigner, the model minority, and problematic representations of gender and sexuality. In the U.S. media, Asians and Asian Americans are greatly underrepresented. Acting roles that are granted to them in television series, films, and shows usually consist of stereotyped characters. It is unacceptable to socialize such stereotypes, for the media play a significant role of education and social networking which help people understand themselves and their relation with others. Within the limited pages of the thesis, I devote to exploring such labels as the “Yellow Peril,” perpetual foreigner, the model minority, the emasculated Asian male and the hyper-sexualized Asian female in the U.S. media. In doing so I hope to promote awareness of such typecasts by white dominant culture and society to ethnic minorities in the U.S. Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation by Yueqin Yang, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of American Studies ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ James M. SoRelle, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Xin Wang, Ph.D. -

Sag – Aftra Television

SAG – AFTRA www.christinaderosa.com TELEVISION (Partial) Mood Swings Series Regular Pure Flix Gravesend Series Regular Amazon Fam Co-Star CBS Black-ish Recurring ABC Jane The Virgin Recurring CW Devious Maids Co-Star Lifetime The Dog Who Saved Summer (MOW) Supporting Lead ION General Hospital Recurring ABC The Astronaut Wives Club Co-Star ABC Hart of Dixie Co-Star CW Foreclosed (MOW) Supporting Lifetime Sam & Cat Co-Star Nickelodeon Taxi Brooklyn Co-Star NBC/EuropaCorp Everybody Hates Chris Guest Star CW Reno 911! Guest Star Comedy Central Worst Week Guest Star CBS Christmas Twister (MOW) Supporting Lead ION The Dog Who Saved Halloween (MOW) Supporting ION Gila (MOW) Lead Syfy Piranhaconda (MOW) Supporting Syfy Entourage Co-Star HBO The Whole Truth Co-Star ABC FILM (Partial) Inheritance Supporting Vaughn Stein Bad Moms Supporting Jon Lucas/Scott Moore A Brother’s Honor Supporting Lane Shefter Bishop The Matchmaker’s Playbook Supporting Tosca Musk Woman on the Edge Supporting Lead Trey Haley Evil Bong 3-D: The Wrath of Bong Lead Charles Band Junk Lead Kevin Hamedani The Grind Lead John Millea Extreme Movie Supporting Epstein/Jacobson Sink Hole Supporting Scott Wheeler The Group Supporting Lawrence Trilling TRAINING Acting - Pamela Shae, Ivana Chubbuck, The Groundlings, Lesly Kahn, Stephen Book, Tim Phillips, Lewis Smith Actors Academy, John Sudol, Larry Moss, Anthony Hopkins Master Class Professional Singer - Nick Cooper, Bob Garrett -- Musical Theater - CMU, Boston Conservatory BA - UCLA School of Theatre, Film & Television SPECIAL SKILLS Professional Singer - Soprano Belt, Dialects - New York, Italian, Spanish, Mexican, Southern . -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C.