Portuguese Nicknames As Surnames 75

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROMAN EMPERORS in POPULAR JARGON: SEARCHING for CONTEMPORARY NICKNAMES (1)1 by CHRISTER BRUUN

ROMAN EMPERORS IN POPULAR JARGON: SEARCHING FOR CONTEMPORARY NICKNAMES (1)1 By CHRISTER BRUUN Popular culture and opposite views of the emperor How was the reigning Emperor regarded by his subjects, above all by the common people? As is well known, genuine popular sentiments and feelings in antiquity are not easy to uncover. This is why I shall start with a quote from a recent work by Tessa Watt on English 16th-century 'popular culture': "There are undoubtedly certain sources which can bring us closer to ordinary people as cultural 'creators' rather than as creative 'consumers'. Historians are paying increasing attention to records of slanderous rhymes, skimmingtons and other ritualized protests of festivities which show people using established symbols in a resourceful way.,,2 The ancient historian cannot use the same kind of sources, for instance large numbers of cheap prints, as the early modern historian can. 3 But we should try to identify related forms of 'popular culture'. The question of the Roman Emperor's popularity might appear to be a moot one in some people's view. Someone could argue that in a highly 1 TIlls study contains a reworking of only part of my presentation at the workshop in Rome. For reasons of space, only Part (I) of the material can be presented and discussed here, while Part (IT) (' Imperial Nicknames in the Histaria Augusta') and Part (III) (,Late-antique Imperial Nicknames') will be published separately. These two chapters contain issues different from those discussed here, which makes it feasible to create the di vision. The nicknames in the Histaria Augusta are largely literary inventions (but that work does contain fragments from Marius Maximus' imperial biographies, see now AR. -

Ballot Name; Use of Nickname Section 99.021, Florida Statutes

DE 86-06 - May 1, 1986 Ballot Name; Use of Nickname Section 99.021, Florida Statutes To: Honorable Ann Robinson, Supervisor of Elections, Indian River County, 1840 - 25th Street, Suite N-109, Vero Beach, Florida 32960-3394 Prepared by: Division of Elections This is in response to your request for an advisory opinion pursuant to Section 106.23(2), Florida Statutes, regarding the use by a candidate as defined by the Florida Election Code, Chapters 97-106, Florida Statutes, of his or her proper name or nickname for appearance on the ballot. Section 99.021, Florida Statutes, requires each candidate to include in his or her oath of candidacy the name as the candidate wishes it to appear on the ballot and directs certification of the name by the qualifying officer to the appropriate supervisor of elections so that the name may thus be printed on the ballot. Under common law principles, not abrogated by Florida law, a name consists of one Christian or given name and one surname, patronymic or family name; therefore, the name printed on the ballot ordinarily should be the Christian or given name and surname, 29 C.J.S. Elections §161. In Florida, a person's legal name is his Christian or given name and family surname, Carlton vs. Phalan, 100 Fla. 1164, 131 So. 117 (1930). However, it has been determined that any name by which a candidate is known is sufficient on a ballot, and a person is legally permitted to have printed on the ballot the name which the candidate has adopted and under which he or she transacts private and official business, 29 C.J.S. -

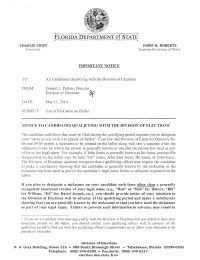

Use of Nickname on Ballot

FLORIDA DEPAR~MENT STATE I . or , CHARLIE CRIST DAWN K. ROBERTS Governor Interim Secretary of State IMPORTANT NOTICE TO: All Candidates Qualifying with the Division of Elections FROM: Donald L. Palmer, Director Division of Elections !If DATE: May 11,2010 SUBJECT: Use of Nickname on Ballot NOTICE TO CANDIDATES QUALIFYING WITH THE DIVISION OF ELECTIONS) The candidate oath form that must be filed during the qualifying period requires you to designate your "name as you wish it to appear on ballot." Case law and Division ofElections Opinions 86 06 and 09-05 permit a nickname to be printed on the ballot along with one's surname when the nickname is one by which the person is generally known or one that the person has used as part of his or her legal name. For example, if John Jones is generally known as Bo Jones, permissible designations on the ballot may be John "Bo" Jones, John (Bo) Jones, Bo Jones, or John Jones. The Division of Elections opinions recognize that a qualifying officer may require the candidate to make a satisfactory showing that the candidate is generally known by the nickname or the nickname has been used as part of the candidate's legal name before a nickname is printed on the ballot. If you plan to designate a nickname on your candidate oath form other than a generally recognized shortened version of your legal name (e.g., "Rob" or "Bob" for Robert, "Bill" for William, "DJ" for David Joseph, etc.), you should provide notice of your intention to the Division of Elections well in advance of the qualifying period and make a satisfactory showing that you are generally known by the nickname or that you have used the nickname as part of your legal name. -

Soups & Stews Cookbook

SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK *RECIPE LIST ONLY* ©Food Fare https://deborahotoole.com/FoodFare/ Please Note: This free document includes only a listing of all recipes contained in the Soups & Stews Cookbook. SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK RECIPE LIST Food Fare COMPLETE RECIPE INDEX Aash Rechte (Iranian Winter Noodle Soup) Adas Bsbaanegh (Lebanese Lentil & Spinach Soup) Albondigas (Mexican Meatball Soup) Almond Soup Artichoke & Mussel Bisque Artichoke Soup Artsoppa (Swedish Yellow Pea Soup) Avgolemono (Greek Egg-Lemon Soup) Bapalo (Omani Fish Soup) Bean & Bacon Soup Bizar a'Shuwa (Omani Spice Mix for Shurba) Blabarssoppa (Swedish Blueberry Soup) Broccoli & Mushroom Chowder Butternut-Squash Soup Cawl (Welsh Soup) Cawl Bara Lawr (Welsh Laver Soup) Cawl Mamgu (Welsh Leek Soup) Chicken & Vegetable Pasta Soup Chicken Broth Chicken Soup Chicken Soup with Kreplach (Jewish Chicken Soup with Dumplings) Chorba bil Matisha (Algerian Tomato Soup) Chrzan (Polish Beef & Horseradish Soup) Clam Chowder with Toasted Oyster Crackers Coffee Soup (Basque Sopa Kafea) Corn Chowder Cream of Celery Soup Cream of Fiddlehead Soup (Canada) Cream of Tomato Soup Creamy Asparagus Soup Creamy Cauliflower Soup Czerwony Barszcz (Polish Beet Soup; Borsch) Dashi (Japanese Kelp Stock) Dumpling Mushroom Soup Fah-Fah (Soupe Djiboutienne) Fasolada (Greek Bean Soup) Fisk och Paprikasoppa (Swedish Fish & Bell Pepper Soup) Frijoles en Charra (Mexican Bean Soup) Garlic-Potato Soup (Vegetarian) Garlic Soup Gazpacho (Spanish Cold Tomato & Vegetable Soup) 2 SOUPS & STEWS COOKBOOK RECIPE LIST Food -

La Rayúa Zona Noroeste El Cabrero Madrileño La Chimenea Casa Pozas Tartajo Kandrak Casa Gómez BASES DEL CONCURSO Cada Vez

Zona Noroeste El Cabrero Casa Kandrak Precio: 11 €. Pozas Tartajo Precio: 18 €. Se sirve: Jueves y viernes. 21 € (Cocción 48 horas). Incluye: Cocido, bebida, postre o café. Precio: 10 € (jueves) y sáb. (17 €). Se sirve: viernes, sábado y domingo. Se sirve: C/ San Juan, 10. Alpedrete. Jueves y sábado. Incluye: Cocido en horno de leña a Incluye: Tel.: 91 857 16 65 Ensalada y cocido completo. baja temperatura, durante 24 horas. Cocido del jueves incl. bebida. No incluye bebida ni postre. El sábado, bebidas aparte. Disponible cocido sin gluten y vegetariano por encargo. Madrileño C/ Dos de Mayo, 4. Guadarrama. Tel.: 91 854 71 83 | 650 81 70 58 C/ Peñalara, 1. Collado Villalba Precio: 19 €. Tel.: 910 263 679 Se sirve: De lunes a viernes. Incluye: Aperitivo, sopa de cocido, Casa Gómez ensalada de tomate raf Cabo de Gata, Precio cocido con sus viandas. : 18 €. Se sirve: De viernes a domingo. El Alto Postres caseros. Bebida: vino tinto Incluye: Altrejo, D.O. Ribera del Duero. cocido completo y postre. Precio:17 € No incl. bebida. Se aconseja reserva. Se sirve: todos los días durante la C/ Doctor Palanca, 3. Guadarrama C/ Emilio Serrano, 32. Cercedilla. VIII Ruta del Cocido Madrileño. Tel.: 91 854 13 08 Tel.: 91 852 01 46 Incluye: Cocido en tres vuelcos, www.restaurantemadrileno.es www.restaurantegomez.es aperitivo, pan, bebida, nuestra torrija caramelizada y café. La Rayúa Avda. Canteros, 11. Alpedrete. La Chimenea Tel.: 910 646 978 Precio: 19 €. www.restauranteelalto.com BASES DEL CONCURSO Precio : 19,25 € Se sirve: Todos los días del año. Se sirve: Todos los jueves. -

Cocido for the Comedor

Cocido for the Comedor 3 tablespoon olive oil 1 tablespoon cumin 1 teaspoon oregano 1 EACH: green, yellow and orange bell peppers, chopped 1 onion sliced 2 cloves of garlic, minced 1 jalapeno, deseeded and minced Kosher salt and black peppercorns to taste (start with about 1 teaspoon each) 2 lbs. pork shoulder or beef shank, cut into chunks 4 cups of water 4 cups chicken broth 2 Large russet potatoes, peeled and cut in 1 inch chunks Other optional vegetables depending on the season and what's on hand might include: 1 16 oz. can hominy or posole, drained 1 carrot cut in 1/2 inch pieces 2 ears of corn cut into 8 pieces 1 zucchini, cut into thick slices, or chayote 1 yellow summer squash, cut into thick slices 1/4 head of Cabbage thinly sliced Garnishes might include: Cilantro, avocado, radishes, fresh salsa Corn tortillas hot and slathered in butter, yellow rice Instructions Season meat with salt and pepper. Set it aside. Heat a large Dutch oven over medium heat. Add oil. Sauté the peppers, onions and garlic in oiluntil limp and beginning to brown, stirring. Then brown the meat in the oil with spices (cumin and oregano). Add water and broth and bring to boil. Skim foam from surface. Cover loosely and simmer for about 2 1/2 hours or until the meat is very tender. Add potato and carrot and simmer for about 25 minutes. Add corn and posole cover and simmer 15 minutes. Then add zucchini, squash and cabbage and cover and simmer 10 minutes or until slightly soft. -

Food Access, Affordability, and Quality in a Paraguayan Food Desert by Meredit

Residence in a Deprived Urban Food Environment: Food Access, Affordability, and Quality in a Paraguayan Food Desert by Meredith Gartin A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved April 2012 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Alexandra Brewis Slade, Chair Amber Wutich Christopher Boone ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY August 2012 ABSTRACT Food deserts are the collection of deprived food environments and limit local residents from accessing healthy and affordable food. This dissertation research in San Lorenzo, Paraguay tests if the assumptions about food deserts in the Global North are also relevant to the Global South. In the Global South, the recent growth of supermarkets is transforming local food environments and may worsen residential food access, such as through emerging more food deserts globally. This dissertation research blends the tools, theories, and frameworks from clinical nutrition, public health, and anthropology to identify the form and impact of food deserts in the market city of San Lorenzo, Paraguay. The downtown food retail district and the neighborhood food environment in San Lorenzo were mapped to assess what stores and markets are used by residents. The food stores include a variety of formal (supermarkets) and informal (local corner stores and market vendors) market sources. Food stores were characterized using an adapted version of the Nutrition Environment Measures Survey for Stores (NEMS-S) to measure store food availability, affordability, and quality. A major goal in this dissertation was to identify how and why residents select a type of food store source over another using various ethnographic interviewing techniques. Residential store selection was linked to the NEMS-S measures to establish a connection between the objective quality of the local food environment, residential behaviors in the local food environment, and i nutritional health status. -

The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany

Kathrin Dräger, Mirjam Schmuck, Germany 319 The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany Abstract The German Surname Atlas (Deutscher Familiennamenatlas, DFA) project is presented below. The surname maps are based on German fixed network telephone lines (in 2005) with German postal districts as graticules. In our project, we use this data to explore the areal variation in lexical (e.g., Schröder/Schneider µtailor¶) as well as phonological (e.g., Hauser/Häuser/Heuser) and morphological (e.g., patronyms such as Petersen/Peters/Peter) aspects of German surnames. German surnames emerged quite early on and preserve linguistic material which is up to 900 years old. This enables us to draw conclusions from today¶s areal distribution, e.g., on medieval dialect variation, writing traditions and cultural life. Containing not only German surnames but also foreign names, our huge database opens up possibilities for new areas of research, such as surnames and migration. Due to the close contact with Slavonic languages (original Slavonic population in the east, former eastern territories, migration), original Slavonic surnames make up the largest part of the foreign names (e.g., ±ski 16,386 types/293,474 tokens). Various adaptations from Slavonic to German and vice versa occurred. These included graphical (e.g., Dobschinski < Dobrzynski) as well as morphological adaptations (hybrid forms: e.g., Fuhrmanski) and folk-etymological reinterpretations (e.g., Rehsack < Czech Reåak). *** 1. The German surname system In the German speech area, people generally started to use an addition to their given names from the eleventh to the sixteenth century, some even later. -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

Issues in the Linguistics of Onomastics

Journal of Lexicography and Terminology, Volume 1, Issue 2 Issues in the Linguistics of Onomastics By Vincent M. Chanda School of Humanities and Social Science University of Zambia Email: mchanda@@gmail.com Abstract Names, also called proper names or proper nouns, are very important to mankind that there is no human language without names and, for some types of names, there are written or unwritten naming conventions. The social importance of names is also the reason why onomastics, the study of names, is a multidisciplinary field. After briefly discussing the multidisciplinary nature of onomastics, the article proves the following view stated and proved by many a scholar: proper names have a grammar that includes some grammatical features of common nouns. In so doing, the article shows that, like common nouns, proper names show cross linguistic differences. To prove that names do have a grammar which in some aspects differs from the grammar of common nouns, the article often compares proper names and common nouns. Furthermore, the article uses data from several languages in addition to English. After a bief discussion of orthographic differences between proper names and common nouns, the article focuses on the morphology, both inflectional and lexical, and the syntax of proper names. Key words: Name, common noun, onomastics, multidisciplinary, naming convention, typology of names, anthroponym, inflectional morphology, lexical morphology, derivation, compounding, syntac. 67 Journal of Lexicography and Terminology, Volume 1, Issue 2 1. Introduction Onomastics or onomatology, is the study of proper names. Proper names are terms used as a means of identification of particular unique beings. -

Global Cuisine, Chapter 2: Europe, the Mediterranean, the Middle East

FOUNDATIONS OF RESTAURANT MANAGEMENT & CULINARY ARTS SECOND EDITION Global Cuisine 2: Europe, the Mediterranean,Chapter # the Middle East, and Asia ©2017 National Restaurant Association Educational Foundation (NRAEF). All rights reserved. You may print one copy of this document for your personal use; otherwise, no part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 and 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without prior written permission of the publisher. National Restaurant Association® and the arc design are trademarks of the National Restaurant Association. Global Cuisine 2: Europe, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Asia SECTION 1 EUROPE With 50 countries and more than 730 million residents, the continent of Europe spans an enormous range of cultures and cuisines. Abundant resources exist for those who want to learn more about these countries and their culinary traditions. However, for reasons of space, only a few can be included here. France, Italy, and Spain have been selected to demonstrate how both physical geography and cultural influences can affect the development of a country’s cuisines. Study Questions After studying Section 1, you should be able to answer the following questions: ■■ What are the cultural influences and flavor profiles of France? ■■ What are the cultural influences and flavor profiles of Italy? ■■ What are the cultural influences and flavor profiles of Spain? France Cultural Influences France’s culture and cuisine have been shaped by the numerous invaders, peaceful and otherwise, who have passed through over the centuries. -

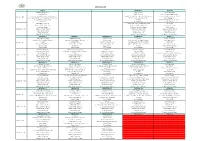

LUNES 1 THURSDAY 1 FRIDAY 2 Lentils Light/Normal Asturian Stew Tortilla Española Soup Castilian Castilian Soup Carrot Cream

MENU APRIL 2018 LUNES 1 THURSDAY 1 FRIDAY 2 Lentils Light/Normal Asturian Stew Tortilla Española Soup Castilian Castilian Soup Carrot Cream Light/Normal Green beans with tomato and potato Tagliatelle with Asparagus and Mushrooms Gnocchi with Tomato and Basil Primer Plato rice with chicken, coconut and Coca-Cola Broccoli with Cheese Cream Stuffed Eggplant Spaghetti with vegetables Paella Rice with Vegetables and Tuna salad Buffet Salad Buffet Salad Buffet Fried eggs with ham Hamburger with Caramelized Onion Pig books hake battered with aioli Peppers Stuffed with Cod cod Encebollado tuna dumplings Barbecue Chicken Wings Cod Fritters Segundo Plato Grilled Chicken Breast Grilled Chicken Breast Grilled Chicken Breast Grilled Fillet of Veal Grilled Fillet of Veal Grilled Fillet of Veal Grilled Pork Loin Grilled Pork Loin Grilled Pork Loin Natural Lunch's Burger Natural Lunch's Burger Natural Lunch's Burger MONDAY 5 TUESDAY 6 WEDNESDAY 7 THURSDAY 8 FRIDAY 9 Lentils Light / Normal Vegetable Soup "Cocido" Soup Fabada Tortilla Española Pumpkin Cream Light / Normal Zucchini Cream Light / Normal Pea cream Vegetable Cream Light/Normal Asparagus Cream Fideua Penne Gratin Raviolis to the Rabiatta Tagliatelle with Tomato and Basil Moussaka Primer Plato Roasted Vegetables Cabbage Riojana Style Artichokes with ham Quiche with Spinach and Bacon Grilled Vegetables Chinese Rice Cod Stew Eggs Gratin Paella Potato Stew with Ribs Salad Buffet Salad Buffet Salad Buffet Salad Buffet Salad Buffet Roasted Chicken Pork with Orange Sauce "Cocido" Chicken Nuggets Meat