MEDEA in OVID's METAMORPHOSES and the OVIDE MORALISE: TRANSLATION AS TRANSMISSION Joel N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth Made Fact Lesson 8: Jason with Dr

Myth Made Fact Lesson 8: Jason with Dr. Louis Markos Outline: Jason Jason was a foundling, who was a royal child who grew up as a peasant. Jason was son of Eason. Eason was king until Pelias threw him into exile, also sending Jason away. When he came of age he decided to go to fulfill his destiny. On his way to the palace he helped an old man cross a river. When Jason arrived he came with only one sandal, as the other had been ripped off in the river. Pelias had been warned, “Beware the man with one sandal.” Pelias challenges Jason to go and bring back the Golden Fleece. About a generation or so earlier there had been a cruel king who tried to gain favor with the gods by sacrificing a boy and a girl. o Before he could do it, the gods sent a rescue mission. They sent a golden ram with a golden fleece that could fly. The ram flew Phrixos and Helle away. o The ram came to Colchis, in the southeast corner of the Black Sea. Helle slipped and fell and drowned in the Hellespont, which means Helle’s bridge (between Europe and Asia). o Phrixos sacrificed the ram and gave the fleece as a gift to the people of Colchis, to King Aeetes. o The Golden Fleece gives King Aeetes power. Jason builds the Argo. The Argonauts are the sailors of the Argo. Jason and the Argonauts go on the journey to get the Golden Fleece. Many of the Argonauts are the fathers of the soldiers of the Trojan War. -

The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018)

The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018) Contents ARTICLES Mother, Monstrous: Motherhood, Grief, and the Supernatural in Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s Médée Shauna Louise Caffrey 4 ‘Most foul, strange and unnatural’: Refractions of Modernity in Conor McPherson’s The Weir Matthew Fogarty 17 John Banville’s (Post)modern Reinvention of the Gothic Tale: Boundary, Extimacy, and Disparity in Eclipse (2000) Mehdi Ghassemi 38 The Ballerina Body-Horror: Spectatorship, Female Subjectivity and the Abject in Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977) Charlotte Gough 51 In the Shadow of Cymraeg: Machen’s ‘The White People’ and Welsh Coding in the Use of Esoteric and Gothicised Languages Angela Elise Schoch/Davidson 70 BOOK REVIEWS: LITERARY AND CULTURAL CRITICISM Jessica Gildersleeve, Don’t Look Now Anthony Ballas 95 Plant Horror: Approaches to the Monstrous Vegetal in Fiction and Film, ed. by Dawn Keetley and Angela Tenga Maria Beville 99 Gustavo Subero, Gender and Sexuality in Latin American Horror Cinema: Embodiments of Evil Edmund Cueva 103 Ecogothic in Nineteenth-Century American Literature, ed. by Dawn Keetley and Matthew Wynn Sivils Sarah Cullen 108 Monsters in the Classroom: Essays on Teaching What Scares Us, ed. by Adam Golub and Heather Hayton Laura Davidel 112 Scottish Gothic: An Edinburgh Companion, ed. by Carol Margaret Davison and Monica Germanà James Machin 118 The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018) Catherine Spooner, Post-Millennial Gothic: Comedy, Romance, and the Rise of Happy Gothic Barry Murnane 121 Anna Watz, Angela Carter and Surrealism: ‘A Feminist Libertarian Aesthetic’ John Sears 128 S. T. Joshi, Varieties of the Weird Tale Phil Smith 131 BOOK REVIEWS: FICTION A Suggestion of Ghosts: Supernatural Fiction by Women 1854-1900, ed. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Resumen ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.Introduction: the legacy ................................................................................................. 3 2. The Classical world in English Literature .................................................................... 6 3. Lady Macbeth, the Scottish Medea ............................................................................ 13 4. Pygmalion: Ovid and George Bernard Shaw ............................................................. 21 5. Upgrading mythology: the American graphic novel .................................................. 33 6. Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 37 BIBLIOGRAPHY .......................................................................................................... 39 1 Resumen El propósito de este escrito es presentar el legado de las culturas griega y romana, principalmente sus literaturas, a través de la historia de la literatura. Aunque ambas tradiciones han tenido un enorme impacto en las producciones literarias de de distintos países alrededor del mundo, esta investigación está enfocada solamente a la literatura inglesa. Así pues, el trabajo iniciará hablando de la influencia de Grecia y Roma en el mundo actual para después pasar al área particular de la literatura. También se tratarán tres ejemplos incluyendo el análisis de tres obras -

C:\Users\User\Documents\04 Reimann\00A-Inhalt-Vorwort.Wpd

Vorwort Aribert Reimann ist einer der erfolgreichsten lebenden Komponisten Deutschlands, von Publikum und Kritik gleichermaßen hoch geschätzt. Bis heute, kurz vor seinem achtzigsten Geburtstag, hat er 78 Vokalwerke kom- poniert. Dazu gehören neben drei Chorwerken und zwei Requiems vor allem Lieder mit Klavier, mit Orchester oder in verschiedenen Kammermusik- besetzungen sowie acht Opern, die weltweit aufgeführt werden. Auch den solistischen Stimmen ohne jede Instrumentalbegleitung bietet Reimann höchst anspruchsvolle Kompositionen: Innerhalb dieses noch immer relativ ungewöhnlichen Genres findet sich neben sieben textinterpretierenden Werken eine sechsteilige Reihe von ganz den ‘Farben’ der menschlichen Stimme nachspürenden Vokalisen. Eine weitere Besonderheit stellen seine Kammermusikbearbeitungen romantischer Klavierlieder von Schubert, Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, Schumann, Brahms und Liszt dar. Obwohl auch die Liste von Reimanns Instrumentalwerken umfangreich und vielfältig ist, konzentriert sich diese Studie ausschließlich auf seine Vokalmusik. Hier kann Reimann aufgrund seiner intimen Vertrautheit mit der menschlichen Stimme aus einem einzigartigen Schatz an Einsichten schöpfen. Seine Affinität zum Gesang hat ihre Basis in seiner Kindheit mit einer Gesangspädagogin und einem Chorleiter als Eltern, in seinen frühen Auftritten als solistischer Knabensopran in konzertanten und szenischen Produktionen und in seiner jahrzehntelangen Erfahrung als Klavierpartner großer Sänger. Den kompositorischen Ertrag dieses Erfahrungsreichtums durch detaillierte Strukturanalysen zu erschließen und in ihrer textinterpre- tierenden Dimension zu würdigen kommt einer Autorin, deren besonderes Interesse dem Phänomen “Musik als Sprache” gilt, optimal entgegen. Die vorliegende Studie stellt in den fünf Hauptkapiteln je fünf Werke aus den vier letzten Dekaden des 20. Jahrhunderts und aus der Zeit seit 2000 vor, darunter die Opern Lear (nach Shakespeare), Die Gespenstersonate (nach Strindberg), Bernarda Albas Haus (nach Lorca) und Medea (nach Grillparzer). -

ON the ORACLE GIVEN to AEGEUS (Eur

ON THE ORACLE GIVEN TO AEGEUS (Eur. Med. 679, 681) Aegeus, according to Euripides the childless king of Athens, consulted the oracle at Delphi on the matter of his childlessness, and was given a puzzling answer. He decided, therefore, to seek an explanation from Pittheus/ king of Troezen, who had the reputation of being a prophetic expert and a wise interpreter. On his way from Delphi to Troezen Aegeus passes through Corinth,1 meets with Medea, and repeats to her the Pythia’s advice: ἀσκοΰ με τὸν προυχοντα μὴ λῦσαι πόδα ... (679) πρὶν ἄν πατρῷαν αΰθις ἐστίαν μόλω. (681) Ί am not to loosen the hanging foot of the wineskin ... until I return again to the hearth of my fathers.’ Medea does not attempt to interpret the oracle, but offers instead to cure Aegeus’ childlessness with drugs when she arrives at his court, and the Athenian king having promised to grant her asylum proceeds to Troezen and to the begetting of Theseus. Ἀ hexametric version of the oracle, which somewhat differs from that of Euripides, appears in Apollod. Bibl. 3, 15, 6 (and in Plut. Thes. 3, 5): ἀσκοΰ τὸν προυχοντα πόδα, μεγα, φερτατε λαῶν, μὴ λυσῃς πρὶν ἐς ἄκρον Ά·θηναίων ἀφίκηνοα. ‘The bulging mouth of the wineskin, Ο best of men, loose not until thou hast reached the height of Athens.’2 1 Cf. T.B.L. Webster, The Tragedies of Euripides (London 1967) 54: ‘It is reasonable that he should pass through Corinth on his way from Delphi to Troezen,’ but cf. Α. Rivier, Essai sur le tragique dEuripide (Lausanne 1944) 55, and the literature cited by him. -

Introduction: Medea in Greece and Rome

INTRODUCTION: MEDEA IN GREECE AND ROME A J. Boyle maiusque mari Medea malum. Seneca Medea 362 And Medea, evil greater than the sea. Few mythic narratives of the ancient world are more famous than the story of the Colchian princess/sorceress who betrayed her father and family for love of a foreign adventurer and who, when abandoned for another woman, killed in revenge both her rival and her children. Many critics have observed the com plexities and contradictions of the Medea figure—naive princess, knowing witch, faithless and devoted daughter, frightened exile, marginalised alien, dis placed traitor to family and state, helper-màiden, abandoned wife, vengeful lover, caring and filicidal mother, loving and fratricidal sister, oriental 'other', barbarian saviour of Greece, rejuvenator of the bodies of animals and men, killer of kings and princesses, destroyer and restorer of kingdoms, poisonous stepmother, paradigm of beauty and horror, demi-goddess, subhuman monster, priestess of Hecate and granddaughter of the sun, bride of dead Achilles and ancestor of the Medes, rider of a serpent-drawn chariot in the sky—complex ities reflected in her story's fragmented and fragmenting history. That history has been much examined, but, though there are distinguished recent exceptions, comparatively little attention has been devoted to the specifically 'Roman' Medea—the Medea of the Republican tragedians, of Cicero, Varro Atacinus, Ovid, the younger Seneca, Valerius Flaccus, Hosidius Geta and Dracontius, and, beyond the literary field, the Medea of Roman painting and Roman sculp ture. Hence the present volume of Ramus, which aims to draw attention to the complex and fascinating use and abuse of this transcultural heroine in the Ro man intellectual and visual world. -

Magic and the Roman Emperors

1 MAGIC AND THE ROMAN EMPERORS (1 Volume) Submitted by Georgios Andrikopoulos, to the University of Exeter as a thesis/dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics, July 2009. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ..................................... (signature) 2 Abstract Roman emperors, the details of their lives and reigns, their triumphs and failures and their representation in our sources are all subjects which have never failed to attract scholarly attention. Therefore, in view of the resurgence of scholarly interest in ancient magic in the last few decades, it is curious that there is to date no comprehensive treatment of the subject of the frequent connection of many Roman emperors with magicians and magical practices in ancient literature. The aim of the present study is to explore the association of Roman emperors with magic and magicians, as presented in our sources. This study explores the twofold nature of this association, namely whether certain emperors are represented as magicians themselves and employers of magicians or whether they are represented as victims and persecutors of magic; furthermore, it attempts to explore the implications of such associations in respect of the nature and the motivations of our sources. The case studies of emperors are limited to the period from the establishment of the Principate up to the end of the Severan dynasty, culminating in the short reign of Elagabalus. -

Faith and Authority in Euripidesâ•Ž Medea and the Bible

Proceedings of GREAT Day Volume 2011 Article 15 2012 Faith and Authority in Euripides’ Medea and the Bible Caitlin Kowalewski SUNY Geneseo Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Kowalewski, Caitlin (2012) "Faith and Authority in Euripides’ Medea and the Bible," Proceedings of GREAT Day: Vol. 2011 , Article 15. Available at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/proceedings-of-great-day/vol2011/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the GREAT Day at KnightScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of GREAT Day by an authorized editor of KnightScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kowalewski: Faith and Authority in Euripides’ <i>Medea</i> and the Bible Faith and Authority in Euripides’ Medea and The Bible Caitlin Kowalewski As people who are essentially foreigners, counterparts accountable to the higher law of the whether geographically or ideologically, Medea, gods who have potentially abandoned her. While Jesus, and his Apostles are forced into positions of she may remain unsure about her own goodness, subservience by the societies in which they live. she is confident in the fact that her enemies have They all exist as minorities, whose actions conflict wronged her, and will be judged by a higher power with social norms. Because of the hostility they for doing so. In her interactions with Creon, we can receive from figures of authority trying to preserve see how this respect for the actions of gods results these norms, their relationships with even higher in disdain for those of men. -

An Analysis of the Modern Medea Figure on the American Stage

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Summer 2013 Three Faces of Destiny: An Analysis of the Modern Medea Figure on the American Stage Melinda M. Marks San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Marks, Melinda M., "Three Faces of Destiny: An Analysis of the Modern Medea Figure on the American Stage" (2013). Master's Theses. 4352. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.d5au-kyx2 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4352 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THREE FACES OF DESTINY: AN ANALYSIS OF THE MODERN MEDEA FIGURE ON THE AMERICAN STAGE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Television, Radio, Film and Theatre San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Melinda Marks August 2013 i © 2013 Melinda Marks ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled THREE FACES OF DESTINY: AN ANALYSIS OF THE MODERN MEDEA FIGURE ON THE AMERICAN STAGE by Melinda Marks APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF TELEVISION, RADIO, FILM AND THEATRE SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY August 2013 Dr. Matthew Spangler Department of Communication Studies Dr. David Kahn Department of Television, Radio, Film and Theatre Dr. Alison McKee Department of Television, Radio, Film and Theatre iii ABSTRACT THREE FACES OF DESTINY: AN ANALYSIS OF THE MODERN MEDEA FIGURE ON THE AMERICAN STAGE By Melinda Marks This thesis examines the ways in which three structural factors contained within three modern American adaptations of Euripides’ Medea serve to enhance the dominant personality traits of the main character. -

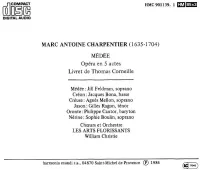

Marc Antoine Charpentier (1635-1704)

mmfi COMPACT HMC 901139. 1 i:irtlt:tiEM DIGITAL AUDIO MARC ANTOINE CHARPENTIER (1635-1704) MEDEE Opéra en 5 actes Livret de Thomas Corneille Médée : Jill Feldman, soprano Créon : Jacques Bona, basse Creuse : Agnès Mellon, soprano Jason : Gilles Ragon, ténor Oronte : Philippe Cantor, baryton Nérine : Sophie Boulin, soprano Chœurs et Orchestre LES ARTS FLORISSANTS William Christie harmonia mundi s.a., 04870 Saint-Michel de Provence (?) 1984 CCS I harmonía c mundi 901139. 1 M E D E E Par <mon(ieur CU ARPE NT ìli R. opéra en 5 actes Jill Feldman Jacques Bona Sophie Boulin Philippe Cantor Agnes Mellon Gilles Ragon "LES ARTS FLORISSANTS' WILLIAM CHRISTIE M E D E E Par <mon[ieur CHARPENTIER. opéra en rj actes LES ARTS FLORISSANTS WILLIAM CHRISTIE ees DISQUE 1 HMC 90.1139 Prologue 1. Ouverture l'S5 2. «Louis est triomphant» 2'19 3. «Paraissez, charmante Victoire» 3'29 4. «Le Ciel dans vos vœux s'intéresse» 4'32 5. Loure - Canaries - Suite des Canaries 3'00 6. «Dans le bel âge si l'on n'est pas volage» 3'16 7. Ouverture (reprise) 1 '52 Acte 1 8. Scène 1 6'42 9. Scène 2 6'34 10. Scène 3 5'07 11. Scène 4 1 '33 12. Scène 5 2'23 13. Scène 6 11 24 Acte II 14. Scène 1 6'44 DISQUE 2 HMC 90.1140 Acte II 1. Scène 2 2'48 2. Scène 3 l'53 3. Scène 4 0'47 4. Scène 5 7'27 5. Scène 6 l'56 6. Scène 7 15'33 Acte III 7. -

Cine Hoyts Ac/E

ÍNDICE CONTENT Colaboradores 08 Partners Sedes 11 Venues Editoriales 13 Editorials Película de Apertura 16 Opening Film Película de Clausura 18 Closing Film Invitados Especiales 21 Special Guests Competencia Internacional 27 International Competition Competencia Nacional 39 National Competition Primer Corte FIDOCS 50 FIDOCS First Cut Panorama Internacional 55 International Panorama Muestra Internacional de “Monsieur Guillaume” Cortometrajes International Short Film “Monsieur Guillaume” 65 Showcase Foco Christian Frei 79 Christian Frei Focus Foco Salomé Lamas 87 Salomé Lamas Focus Foco Eric Baudelaire 97 Eric Baudelaire Focus Escuela FIDOCS 106 FIDOCS School Anexos 109 Appendices A ÍNDICE POR PELÍCULA 100 [sic] 103 Also Known as Jihadi 30 Amal FILM INDEX 31 Antígona 56 Ata tu arado a una estrella 32 Buenos Aires al Pacífico 42 Can Limbo 19 Cien niños esperando un tren 93 Coup de Grâce 67 Curupira, bicho do mato 17 De la joie dans ce combat 92 ElDorado XXI 95 Extinção 85 Genesis 2.0 43 Hoy y no mañana 57 Introduzione all’oscuro 58 Iphigenia in Aulis 68 L. Cohen 69 La casa de Julio Iglesias 33 La estrella errante 70 La extraña 44 Las cruces 102 Letters to Max 71 Los que desean 72 Los que vinieron antes 44 Los sueños del castillo 34 M 59 Matangi / Maya / M.I.A. 76 Montañas ardientes que vomitan fuego 35 O processo 77 Plus Ultra 82 Ricardo, Miriam y Fidel 75 Sin Dios ni Santa María 84 Sleepless in New York 73 Solo queda el simulacro 60 Teatro de guerra 91 Theatrum Orbis Terrarum 90 Terra de Ninguém 101 The Anabasis of May and F.S., M.A. -

Medea |Sample Answer

Medea | Sample answer 2006 Higher Level Exam Question What insights does Euripides’ play “Medea” give us into the different ways women and men viewed marriage at the time? There is no denying that men and women had different views of marriage. Euripides provides excellent insights in the play Medea. This difference am be seen when Medea makes her first speech to the chorus after finding out Jason is interested in marrying another. Medea speaks of marriage almost like a trap. They are bought and sold like objects, taken from their homes and forced to lead a new life. Medea explains that women must always “Look to one man only.” She must stay at home and she is never allowed to be too intelligent. What is even worse is that men can wander and look for pleasure elsewhere if they get bored. “If a man grows tired of the company at home, he can go out, and find a cure for tediousness.” There is a double standard for men with regards to remaining loyal at this time. Men are allowed to be unfaithful but “for women, divorce is not respectable; to repel the man, not possible.” This clearly displays how women had to be faithful and constantly loyal in marriage whereas men could be as unfaithful as they liked and the marriage would still continue. It is clear that women viewed marriage as sacred and central to their identity. By Jason leaving Medea, he has taken everything away from her. As a result of her loss of status and power, the chorus and the nurse are completely on her side.