Juan Downey El Ojo Pensante Indice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First U.S. Survey of Chilean Artist Juan Downey to Open at Bronx Museum of the Arts

FIRST U.S. SURVEY OF CHILEAN ARTIST JUAN DOWNEY TO OPEN AT BRONX MUSEUM OF THE ARTS Video and Photographic Installations, Paintings, and Drawings shed light on Downey’s Career Bronx, NY , DATE – Beginning February 9, 2012 The Bronx Museum of the Arts will present Juan Downey: The Invisible Architect , the first U.S. survey of the pioneering video artist Juan Downey. On view through May 20, 2012, the exhibition brings together more than 100 works from Downey’s expansive career, from his early experimental work with art and technology to his groundbreaking video art from the 1970s through the 1990s, the exhibition will include drawings, paintings, video and photographic installations, and the artist’s notebooks, which have never before been on view. “Downey revolutionized the field of video art and pioneered an art form that has had continued relevance for contemporary artists working today,” said Bronx Museum of the Arts Director Holly Block. “As a Chilean, Downey maintained a connection with Latin American culture throughout the many decades he lived and worked in New York. These dual influences give his work a special resonance with the Bronx Museum and with our community. In addition, Downey has exhibited at the Bronx Museum before, making this exhibition a homecoming of sorts.” Formally trained as an architect, Downey began experimenting with different art forms when he moved from Paris to Washington DC in 1965. He developed a strong interest in the concept of invisible energy and shifted from object-based artistic practice to an experiential approach, seeking to combine interactive performance with sculpture and video, a transition the exhibition explores. -

The Social and Environmental Turn in Late 20Th Century Art

THE SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL TURN IN LATE 20TH CENTURY ART: A CASE STUDY OF HELEN AND NEWTON HARRISON AFTER MODERNISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN MODERN THOUGHT AND LITERATURE AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY LAURA CASSIDY ROGERS JUNE 2017 © 2017 by Laura Cassidy Rogers. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/gy939rt6115 Includes supplemental files: 1. (Rogers_Circular Dendrogram.pdf) 2. (Rogers_Table_1_Primary.pdf) 3. (Rogers_Table_2_Projects.pdf) 4. (Rogers_Table_3_Places.pdf) 5. (Rogers_Table_4_People.pdf) 6. (Rogers_Table_5_Institutions.pdf) 7. (Rogers_Table_6_Media.pdf) 8. (Rogers_Table_7_Topics.pdf) 9. (Rogers_Table_8_ExhibitionsPerformances.pdf) 10. (Rogers_Table_9_Acquisitions.pdf) ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Zephyr Frank, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Gail Wight I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ursula Heise Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. -

Juan Downey | a Communications Utopia Detail of Life Cycle

juan downey | a communications utopia Detail of Life Cycle. Soil + Water + Air+ Light = Flowers + Bees = Honey, All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace Electric Gallery, Toronto, Canada, 1971. Photo: Courtesy Marilys Belt de Downey, N.Y. I like to think (and the sooner the better!) of a cybernetic meadow where mammals and computers live together in mutually programming harmony like pure water touching clear sky. I like to think (right now, please!) of a cybernetic forest filled with pines and electronics where deer stroll peacefully past computers as if they were flowers with spinning blossoms. I like to think (it has to be!) of a cybernetic ecology where we are free of our labors and joined back to nature, returned to our mammal brothers and sisters, and all watched over by machines of loving grace. Richard Brautigan, 1967 juan downey | a communications utopia Trained as an architect, the topological experience of video feedback led Downey to conceive of dematerialized and ecological architectures through drawings of projects for buildings and cities that promoted the flow of energy between nature and the built environment. One of Downey’s landmark works is the video-feedback-based installation Video Trans Americas. In 1973 he embarked on a journey that would take him from New York to Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, The work of Juan Downey (Santiago de Chile, 1940 – New York, Bolivia, and Chile, where he recorded the autochthonous cultures of 1993) covers a wide range of practices and mediums: drawing, each place and then showing them to the inhabitants of these places installation, video, and painting. -

J. Paul Getty Trust Report 2016 Culture at Risk

J. Paul Getty Trust Report 2016 Culture at Risk - J. Paul Getty Trust Report 2016 On Cover: Triumphal arch and great colonnade, Palmyra, Syria (no. 62), 1864, Louis Vignes. From Louis Vignes, Views and panoramas of Beirut and the ruins of Palmyra, 1864. (GRI) Table of Contents 2 Chair Message Maria Hummer-Tuttle, Chair, Board of Trustees 4 Foreword James Cuno, President and CEO, J. Paul Getty Trust 8 Culture at Risk 9 Targeting History Richard Haass, President of the Council on Foreign Relations 15 Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, Director 23 Getty Foundation Deborah Marrow, Director 33 J. Paul Getty Museum Timothy Potts, Director 41 Getty Research Institute Thomas W. Gaehtgens, Director 51 2016 Highlights 69 Trust Report Lists 70 Getty Conservation Institute Projects 82 Getty Foundation Grants 94 Exhibitions and Acquisitions 116 Getty Guest Scholars 120 Getty Publications 126 Getty Councils 134 Honor Roll of Donors 138 Board of Trustees, Officers, and Directors 139 Financial Information Chair Message MARIA HUMMER-TUTTLE, CHAIR, BOARD OF TRUSTEES J. Paul Getty Trust One of the Getty’s strategic priorities is to grants to date to support scholarly research and to assist achieve leadership in online access to art, archives, in funding many of the exhibitions. I want to thank and digital publications—both for professionals and the Pacific Standard Time Leadership Council, a group for the general public. The GRI is now digitizing of generous donors, for their support. Together with approximately 952 books per month from its foundation and corporate donations, they are funding collection, a 97 percent increase over the previous year. -

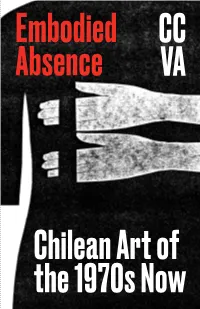

Embodied Absence Chilean Ar

Embodied Absence Chilean Art of the 1970s Now Carpenter Center Embodied Absence for the Visual Arts Chilean Art of the 1970s Now Oct 27, 2016–Jan 8, 2017 Works by Elías Adasme, Carmen This exhibition is co-organized Beuchat with Felipe Mujica and with DRCLAS as part of its research Johanna Unzueta, CADA (Colectivo project Conceptual Stumblings. Acciones de Arte), Francisco Copello, Exhibition and program support Luz Donoso, Juan Downey, Carlos is also provided by Harvard Leppe, Catalina Parra, Lotty University Committee on the Rosenfeld, UNAC (Unión por la Arts. The first iteration, Embodied Cultura), Cecilia Vicuña, and Raúl Absence: Ephemerality and Zurita with Cristóbal Lehyt Collectivity in Chilean Art of the 1970s (September 2015–January Guest curated by Liz Munsell, 2016), was organized by Museo Assistant Curator of Contemporary de la Solidaridad Salvador Art & Special Initiatives, Museum of Fine Allende, Santiago, Chile, with its Arts, Boston, and visiting curator, David substantial support in research Rockefeller Center for Latin American and production of works, in Studies (DRCLAS), Harvard University collaboration with DRCLAS. Embodied Absence Liz Munsell Following the U.S.-backed coup d’état in 1973,1 Chilean artists residing in Santiago and abroad created artworks that spoke to their experience of political, social, and geographic marginalization. Inside the country, they adopted the highly coded languages of conceptual art to evade censorship, exhibited work in public space in lieu of institutional support, and formed independently run galleries and artist collectives to protect their individual identities. Artists abroad staged public events and made artwork in solidarity with those at home. Their exhibitions, performances, interventions, and workshops spread awareness among international audiences and broke down isolating conditions within Chile. -

Juan Downey's Communications Utopia

JUAN DOWNEY’S COMMUNICATIONS UTOPIA Julieta González “The power of the arts to anticipate future social and technological developments by a generation and more has long been recognized. In this century Ezra Pound called the artist «the antennae of the race». Art as radar acts as «an early alarm system», as it were, enabling us to discover social and psychic targets in lots of time in order to prepare to cope with them. This concept of the arts as prophetic contrasts with the popular idea of them as merely a form of self-expression. If art is an «early warning system» to use the phrase from World War II, when radar was new, art has the utmost relevance not only to the study of media but to the development of media controls.” Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media, 1964 McLuhan’s statement reflects a shared sentiment within the artistic community in the 60s; that artists could pick up the signals emitted by scientific progress and put their particular sensibilities and discursive strategies at the service of society at large. Juan Downey was one such artist, who foresaw the future of technology as a social driving force, and in correspondence with this vision manifested a constant concern for the relations between humankind and technology throughout his prolific career. Downey's practice developed against the backdrop of cybernetics' systemic view of the world; one recast in computational terms as a series of homeostatic systems regulated by feedback dynamics. This essay thus attempts to map the influence of cybernetic thought on Juan Downey’s entire oeuvre, identifying it as the connecting thread that runs through his diverse and heterogeneous bodies of work; from his early electronic sculptures to the deconstruction of the ethnographic canon in the works he produced as the result of his stay with the Yanomami in the mid-seventies. -

Juan Downey Juan Downey

1 Juan Downey Juan Downey Juan Downey nació en Santiago el 11 de mayo de 1940 y falleció en Nueva York el 9 de junio de 1993. Biografía Juan Downey Alvarado nació en Santiago, Chile el 11 de mayo de 1940. Downey egresó en 1961 de la carrera de arquitectura en la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Paralelamente, estudió grabado en el Taller 99 , fundado en 1956 por el artista Nemesio Antúnez . Luego de recibir el título de arquitecto Downey decide ir a Europa para profundizar su educación artística. Primero estudia pintura en Madrid y Barcelona (España), y más tarde viaja a París (Francia), donde continúa sus estudios en torno a la técnica del grabado en metal en el Atelier 17, al alero del maestro grabador y fundador del Atelier William Hayter, donde también estudiaron los artistas chilenos Roberto Matta (Nueva York) y Eugenio Téllez (París). Luego de su estadía en Europa, viaja en 1965 a Washington D.C., Estados Unidos. En 1967 se traslada a Nueva York, para estudiar en la Escuela de Arquitectura, Arte y Diseño del Pratt Institute, institución en la que más tarde ejerció como profesor hasta su fallecimiento. El artista desarrolló su obra en diferentes medios, entre las que se cuentan el grabado, el dibujo , la pintura , la performance , la instalación y el videoarte , siendo considerado uno de los pioneros del arte electrónico y del videoarte a nivel mundial. Entre los principales temas de interés para su producción artística se encuentran las relaciones entre arte, ciencia y tecnología, la arquitectura, la psicología y la antropología, además de las temáticas autobiográficas. -

Juan Downey's

Issue 11 BLOOD AND EARTH AND SOIL ISSUE 11: BLOOD AND EARTH AND SOIL Christopher Green From the Editors Dana Liljegren ARTICLES 1. Max Bonhomme Human scale and the technological sublime. An iconology of the ‘crisis of civilization’ in the 1930s 2. Julia Bozer Juan Downey’s “Anaconda” Map of Chile, 1975 3. Trangđài Glassey- Un/Earthing Borderland-Motherland: Stateless Trầnguyễn Bodies Intimating the Waves, the Woods, and the Walls 4. Alyssa Bralower Land Grant: Complicating Institutional Legacies Allison Rowe SPECIAL FEATURE 5. Anne Spice Give us our Knives ARTIST PROJECT 6. Jackson Polys Morph Target Displacement Mapping: Zack Khalil Removals / Pre-Creative Acts Adam Khalil DISPATCH 7. Teresa Retzer The resurgence of Blood and Soil: symbols and artefacts of Völkische Siedlungen and Neo-Nazi Villages in Germany REVIEWS 8. Stephanie Lebas Huber Review: De Wereld van Pyke Koch 9. Crystal Migwans A Monumental Undertaking 10. Horacio Ramos On Representation, Appropriation, and Everything in Between Cover artwork: Adam Khalil, Zack Khalil, and Jackson Polys, Morph Target Displacement Mapping: Removals / Pre-Creative Acts (details), 2019. © Jackson Polys, Zack Khalil, and Adam Khalil. Shift: Graduate Journal of Visual and Material Culture From the Editors CHRISTOPHER GREEN DANA LILJEGREN “Whose blood and soil?” asked a subheading in a recent article by The Economist about the rise of Native American politicians in the United States.1 The question was posed to suggest that the stunning victories of Native American Congressional and local state representatives in the 2018 midterm elections represented a challenge to the Trumpian dogma that white nativists have a proprietorial claim to America. -

Downey Final Press Release

Contact: Mark Linga [email protected] 617.452.3586 NEWS RELEASE The MIT List Visual Arts Center in collaboration with The Bronx Museum of the Arts presents Juan Downey: The Invisible Architect May 5—July 12, 2011 Hayden, Reference, Bakalar Galleries Opening Reception: Wednesday, May 4, 2011, 6-8PM Reception preceded by a conversation with catalogue essayist Gustavo Buntinx and Marilys Belt de Downey, moderated by curator Valerie Smith at 5:30 PM in the Bartos Theatre Juan Downey, JS Bach, 1986 Courtesy Marilys Belt de Downey Cambridge, MA—April 2011. The MIT List Visual Arts Center and The Bronx Museum of Art are pleased to present Juan Downey: The Invisible Architect. This exhibition is the first US museum survey of Juan Downey, who was born in Chile, educated in Chile and France, and lived for the major part of his career in New York City. A fellow at MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies in 1973 and 1975, Downey played a significant role in the New York art scene of the 1970s and ‘80s. The exhibition is organized by curator Valerie Smith, Head of the Department of Visual Art, Film, and Media at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, in Berlin, Germany. The exhibition will travel to the Arizona State University Art Museum, Tempe, AZ (September 24-December 31, 2011) and the Bronx Museum of the Arts in New York (February 12-May 20, 2012). Covering several decades of the artist’s work, The Invisible Architect includes Downey’s early experiments with art and technology when he began to shift from an object-based artistic practice to an experiential approach that aimed to combine interactive performance with sculpture and video. -

REWIND a Guide to Surveying the First Decade: Video Art and Alternative Media in the U.S., 1968-1980

REWIND A Guide to Surveying the First Decade: Video Art and Alternative Media in the U.S., 1968-1980 REWIND A Guide to Surveying the First Decade: Video Art and Alternative Media in the U.S., 1968-1980 REWIND 1995 edition Editor: Chris Hill Contributing Editors: Kate Horsfield, Maria Troy Consulting Editor: Deirdre Boyle REWIND 2008 edition Editors: Abina Manning, Brigid Reagan Design: Hans Sundquist Surveying the First Decade: Video Art and Alternative Media in the U.S., 1968–1980 1995 VHS edition Producer: Kate Horsfield Curator: Chris Hill Project Coordinator: Maria Troy Produced by the Video Data Bank in collaboration with Electronic Arts Intermix and Bay Area Video Coalition. Consultants to the project: Deirdre Boyle, Doug Hall, Ulysses Jenkins, Barbara London, Ken Marsh, Leann Mella, Martha Rosler, Steina Vasulka, Lori Zippay. On-Line Editor/BAVC: Heather Weaver Editing Facility: Bay Area Video Coalition Opening & Closing Sequences and On-Screen Titles: Cary Stauffacher, Media Process Group Preservation of Tapes: Bay Area Video Coalition Preservation Supervisor: Grace Lan, Daniel Huertas Special thanks: David Azarch, Sally Berger, Peer Bode, Pia Cseri-Briones, Tony Conrad, Margaret Cooper, Bob Devine, Julia Dzwonkoski, Ned Erwin, Sally Jo Fifer, Elliot Glass, DeeDee Halleck, Luke Hones, Kathy Rae Huffman, David Jensen, Phil Jones, Lillian Katz, Carole Ann Klonarides, Chip Lord, Nell Lundy, Margaret Mahoney, Marie Nesthus, Gerry O’Grady, Steve Seid, David Shulman, Debbie Silverfine, Mary Smith, Elisabeth Subrin, Parry Teasdale, Keiko -

Anaconda” Map of Chile, 1975

Juan Downey’s “Anaconda” Map of Chile, 1975 JULIA BOZER We might perhaps say that wherever suffering and helpless humanity is found in blind quest for salvation, the snake will be close by, as an explanatory image of the cause. —Aby Warburg1 In April 1975, Juan Downey’s solo show, “Energy Systems,” opened at the Center for Inter-American Relations (CIAR) in Manhattan. At its center was an installation entitled Map of Chile, which featured a live green anaconda slithering atop a map of Downey’s native Chile (fig. 1). The artist had salvaged the map from a trashcan near the Chilean Embassy in Washington, D.C., colored it in by hand, and used it to line the bottom of a plexiglass-covered box.2 Air holes were drilled along each edge, and a small pool of water was added to the base, in order to sustain the snake. “Energy Systems” represented Downey’s second exhibition at the CIAR—he had participated in its group show of “Latin American New Painting and Sculpture” in November 1969—but it was to be his most eventful, for within hours of its performative debut the anaconda was forcibly removed from the venue. Downey opted to leave the rest of his piece intact, adding a handwritten note half explaining the act of censorship (fig. 2).3 His audience was left to wonder how, exactly, the snake had offended. The relationship between the anaconda and the map of Chile has resonance on multiple levels. Most obviously, the snake and the country bear a distinct morphological affinity. -

Patricia Johnston Is Professor of Art History at Salem State College

Abstracts for Encuentros: Artistic Exchange between the U.S. and Latin America “Ambas Américas/Two Americas: A Proposal for Studying the Nineteenth Century” Katherine Manthorne My paper proposes to interrogate the intellectual and geographic boundaries of artistic encounters across the Americas during the nineteenth century. In other disciplines and at various historic moments the “transnational turn” has taken on currency; however, art history has been slower to abandon its traditional organization around nation states or religions. The current mandate for globalism undermines the field’s foundations, but has yet to offer successful alternative paradigms. Utilizing transnational and hemispheric studies, the strategies suggested by this paper do not intend to displace national, identity-based categories, but rather, they aim to reiterate America’s connectedness across the hemisphere and around the globe. To achieve these goals, this paper summarizes briefly the historical and theoretical underpinnings for a hemispheric approach, from José Martí and Herbert E. Bolton until today. I then scrutinize the intellectual terrain of the art history of the Americas as it is currently studied. While the Encuentros program represents some of the best scholarship in the field, it is almost exclusively focused on the twentieth century. This gap underscores the fact that the nineteenth century, to date, is largely omitted from our field of inquiry. Since this was the era when many of the existing political and cultural relations between North and South America were established, how can we continue to leave it aside? This lacuna motivates us to consider models and methods that bring the art of ambas Américas—the two Americas—into dialogue from independence to the great international expositions at the century’s end.