Juan Downey's Communications Utopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First U.S. Survey of Chilean Artist Juan Downey to Open at Bronx Museum of the Arts

FIRST U.S. SURVEY OF CHILEAN ARTIST JUAN DOWNEY TO OPEN AT BRONX MUSEUM OF THE ARTS Video and Photographic Installations, Paintings, and Drawings shed light on Downey’s Career Bronx, NY , DATE – Beginning February 9, 2012 The Bronx Museum of the Arts will present Juan Downey: The Invisible Architect , the first U.S. survey of the pioneering video artist Juan Downey. On view through May 20, 2012, the exhibition brings together more than 100 works from Downey’s expansive career, from his early experimental work with art and technology to his groundbreaking video art from the 1970s through the 1990s, the exhibition will include drawings, paintings, video and photographic installations, and the artist’s notebooks, which have never before been on view. “Downey revolutionized the field of video art and pioneered an art form that has had continued relevance for contemporary artists working today,” said Bronx Museum of the Arts Director Holly Block. “As a Chilean, Downey maintained a connection with Latin American culture throughout the many decades he lived and worked in New York. These dual influences give his work a special resonance with the Bronx Museum and with our community. In addition, Downey has exhibited at the Bronx Museum before, making this exhibition a homecoming of sorts.” Formally trained as an architect, Downey began experimenting with different art forms when he moved from Paris to Washington DC in 1965. He developed a strong interest in the concept of invisible energy and shifted from object-based artistic practice to an experiential approach, seeking to combine interactive performance with sculpture and video, a transition the exhibition explores. -

The Social and Environmental Turn in Late 20Th Century Art

THE SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL TURN IN LATE 20TH CENTURY ART: A CASE STUDY OF HELEN AND NEWTON HARRISON AFTER MODERNISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN MODERN THOUGHT AND LITERATURE AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY LAURA CASSIDY ROGERS JUNE 2017 © 2017 by Laura Cassidy Rogers. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/gy939rt6115 Includes supplemental files: 1. (Rogers_Circular Dendrogram.pdf) 2. (Rogers_Table_1_Primary.pdf) 3. (Rogers_Table_2_Projects.pdf) 4. (Rogers_Table_3_Places.pdf) 5. (Rogers_Table_4_People.pdf) 6. (Rogers_Table_5_Institutions.pdf) 7. (Rogers_Table_6_Media.pdf) 8. (Rogers_Table_7_Topics.pdf) 9. (Rogers_Table_8_ExhibitionsPerformances.pdf) 10. (Rogers_Table_9_Acquisitions.pdf) ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Zephyr Frank, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Gail Wight I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ursula Heise Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. -

I. Those Present and Approval of Minutes of Regular Quarterly Meeting of May I, 1967

AGENDA The Board of Trustees October 30, 1967 (The Corcoran Gallery of Art Centennial: May IS, 1969) I. Those present and approval of minutes of Regular Quarterly meeting of May I, 1967. a) Resolution on the death of Mr. Fleming Bomar, President of The Friends of the Corcoran. l/ 2. Auditors Report for year ending December 31, 1966. 3. Treasurer's Interim Report. r; Report on Operation of the Budget. I___5> Financial report on the Art School for period September I, 1966 - August 31, 1967. 6. Financial report on the 1967 Summer School. Approval of Consolidated Endowment Fund. ^-3. Report on receipts from paid admissions for May - September 30, 1967. 9. Consideration of letter from Edmund Archer requesting sab- aticaI Ieave. 10. Report submitted by John Price Jones & Gale Associates. I I . ResoIution of thanks for the following gifts: This page was intentionally removed due to a research restriction on all Corcoran Gallery of Art Development and Membership records. Please contact the Public Services and Instruction Librarian with any questions. -3- Report on Membership: a) Art School student members. b) Report American Mail Advertising membership survey and results. c) Resolution on election of Fellow in the Association. Report of the Committee on Bui Iding and Grounds for Second and Third Quarters. a) Letter from General Services Administration re availa¬ bility of land in this block, b) Consideration of excavation to provide more parking// space in garden area. 16. Report of the Special Committee on Music. Financial report of the Women's Committee for period August I, 1966 through August 22, 1967 and minutes of meetings of May 23, 1967 and September 26, 1967. -

Electronic Zen

ELECTRONIC ZEN: The Alternate Video Generation By Jud Yalkut Copyright, 1984, Jud Yalkut. "The light-flower of heaven and earth fills all the thousand spaces. But also the light-flower of the individual body passes through heaven and covers the earth. Therefore, as soon as the light is circulating, heaven and earth, mountains and rivers, are all circulating with it at the same time. To concentrate the seed-flower of the human body above in the eyes, that is the great key of the human body." - THE SECRET OF THE GOLDEN FLOWER. "Zen Meditation is purely a subjective experience completed by a concentration which holds the inner mind calm, pure and serene. And yet Zen meditation produces a special psychological state based on the changes in the electroencephalogram. Therefore, Zen meditation influences not only the psychic life but also the physiology of the brain." - AKIRA KASAMATSU AND TOMIO HIRAI ("An Electroen- cephalographic Study on the Zen Meditation (Zazen)") in ALTERED STATES OF CONSCIOUSNESS (Charles Tart, editor). "We are not yet aware that telepathy is conveyed through the resonance factors of the mind... The electromagnetic vibration of the head might lead the way to Electronic Zen." - NAM JUNE PAIK. ELECTRONIC ZEN: THE ALTERNATE VIDEO GENERATION PREFACE Although the medium of television has existed in the American home since the post-war period, it has only been since the advent of portable video recorders in the late sixties that a meaningful dissemination of electronics communication technology has permitted the two-way interf low of information and vision exchange. This predominantly half-inch video technology engendered the emergence of alternate video innovators who have gradually mastered the parameters and circuitry of equipment woefully unstable as com pared to the hardware used daily by the vast television broadcasting networks. -

Michael Clark (A.K.A

ARTIST MICHAEL CLARK: WASHINGTON April 3 – May 27, 2018 American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center Washington, DC ALPER INITIATIVE FOR WASHINGTON ART FOREWORD Michael Clark (a.k.a. Clark Fox) has been an influential figure in the Washington art world for more than 50 years, despite dividing his time equally between the capital and New York City. Clark was not only a fly on the wall of the art world as the last half- century played out—he was in the middle of the action, making innovative works that draw their inspiration from movements as diverse as Pop Art, Op Art, Conceptual Art, Minimalism, and the Washington Color School. The result of this prolific and varied artistic oeuvre is that Clark’s output is too much for one show. After consulting with former Washington Post art critic Paul Richard, I decided Michael Clark: Washington Artist at the American University Museum would concentrate on his significant artistic contributions to the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s in Washington, DC. In line with his amazingly diverse and productive career, a conversation with Michael Clark is similar to drinking from a fire hose. In one sentence, he can jump from painting techniques using masking tape to making cookies for Jackie Onassis. My transcription of our conversation, presented here as a soliloquy, tries its best to maintain some kind of coherence and order, but in reality, I just tried to hold on for the ride. In contrast, the amazing thing about Clark’s art is how still, focused, and composed it is. The leaps and diversions of his lively mind are transmuted into an almost classical art, more Modigliani than Soutine, probably reflecting the time spent in his early years copying masterworks in the National Gallery of Art. -

Free Art and a Planned Giveaway

54 ARCHIVES of AMERICAN ART JOURNAL | 57.1 fig. 9 Letter from Henri Ehrsam to Gene Davis, June 29, 1965. Henri Gallery Records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. first attempt to create the paintings, using local art students, so poor that he refused to put his name to them.40 McGowin ultimately enlisted Michael Clark (now known as Clark V. Fox), a recent graduate of the Corcoran School of Art and a skilled artist, to paint the fifty copies.41 The process of mass-reproducing Popsicle highlighted a hierarchy of labor in Giveaway, by which the physical production of the work was subordinate to its conception. Working on five canvases at a time, twelve to sixteen hours a day for nine days, and paid less than a skilled worker’s hourly wages plus meals, Clark painted all fifty works.42 Extant canvases bear the silkscreened names of the three event organizers followed by Clark’s original signature, with some—but not all—of the works also signed by Clark’s assistants ( fig. 10).43 In effect diminishing the painter and fabricators’ skill and artistic contributions, Douglas Davis declared “although his work is original and profound, in some ways Gene Davis is an easy copy.”44 Like Sturtevant’s repetitions, the copies of Popsicle were not exact.45 Mixing pigments to produce the exact hues of the original painting was challenging, given the brevity of Davis’s instructions.46 Moreover, at least one critic noted stylistic differences between Davis’s and Clark’s stripes; the older artist had been interested in how overlapping colors could produce faint effects of subtle vibration, but Clark did not have the luxury of letting one stripe dry before painting the next.47 Subtle aesthetic differences between the original and its reproductions produced fresh skepticism about a model of creative practice unable to see beyond the dichotomy of author and nonauthor. -

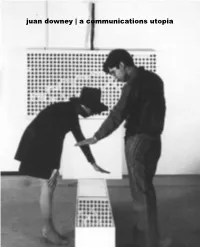

Juan Downey | a Communications Utopia Detail of Life Cycle

juan downey | a communications utopia Detail of Life Cycle. Soil + Water + Air+ Light = Flowers + Bees = Honey, All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace Electric Gallery, Toronto, Canada, 1971. Photo: Courtesy Marilys Belt de Downey, N.Y. I like to think (and the sooner the better!) of a cybernetic meadow where mammals and computers live together in mutually programming harmony like pure water touching clear sky. I like to think (right now, please!) of a cybernetic forest filled with pines and electronics where deer stroll peacefully past computers as if they were flowers with spinning blossoms. I like to think (it has to be!) of a cybernetic ecology where we are free of our labors and joined back to nature, returned to our mammal brothers and sisters, and all watched over by machines of loving grace. Richard Brautigan, 1967 juan downey | a communications utopia Trained as an architect, the topological experience of video feedback led Downey to conceive of dematerialized and ecological architectures through drawings of projects for buildings and cities that promoted the flow of energy between nature and the built environment. One of Downey’s landmark works is the video-feedback-based installation Video Trans Americas. In 1973 he embarked on a journey that would take him from New York to Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, The work of Juan Downey (Santiago de Chile, 1940 – New York, Bolivia, and Chile, where he recorded the autochthonous cultures of 1993) covers a wide range of practices and mediums: drawing, each place and then showing them to the inhabitants of these places installation, video, and painting. -

J. Paul Getty Trust Report 2016 Culture at Risk

J. Paul Getty Trust Report 2016 Culture at Risk - J. Paul Getty Trust Report 2016 On Cover: Triumphal arch and great colonnade, Palmyra, Syria (no. 62), 1864, Louis Vignes. From Louis Vignes, Views and panoramas of Beirut and the ruins of Palmyra, 1864. (GRI) Table of Contents 2 Chair Message Maria Hummer-Tuttle, Chair, Board of Trustees 4 Foreword James Cuno, President and CEO, J. Paul Getty Trust 8 Culture at Risk 9 Targeting History Richard Haass, President of the Council on Foreign Relations 15 Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, Director 23 Getty Foundation Deborah Marrow, Director 33 J. Paul Getty Museum Timothy Potts, Director 41 Getty Research Institute Thomas W. Gaehtgens, Director 51 2016 Highlights 69 Trust Report Lists 70 Getty Conservation Institute Projects 82 Getty Foundation Grants 94 Exhibitions and Acquisitions 116 Getty Guest Scholars 120 Getty Publications 126 Getty Councils 134 Honor Roll of Donors 138 Board of Trustees, Officers, and Directors 139 Financial Information Chair Message MARIA HUMMER-TUTTLE, CHAIR, BOARD OF TRUSTEES J. Paul Getty Trust One of the Getty’s strategic priorities is to grants to date to support scholarly research and to assist achieve leadership in online access to art, archives, in funding many of the exhibitions. I want to thank and digital publications—both for professionals and the Pacific Standard Time Leadership Council, a group for the general public. The GRI is now digitizing of generous donors, for their support. Together with approximately 952 books per month from its foundation and corporate donations, they are funding collection, a 97 percent increase over the previous year. -

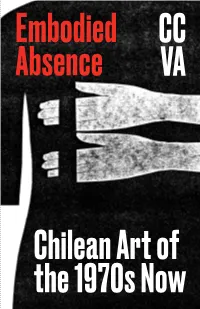

Embodied Absence Chilean Ar

Embodied Absence Chilean Art of the 1970s Now Carpenter Center Embodied Absence for the Visual Arts Chilean Art of the 1970s Now Oct 27, 2016–Jan 8, 2017 Works by Elías Adasme, Carmen This exhibition is co-organized Beuchat with Felipe Mujica and with DRCLAS as part of its research Johanna Unzueta, CADA (Colectivo project Conceptual Stumblings. Acciones de Arte), Francisco Copello, Exhibition and program support Luz Donoso, Juan Downey, Carlos is also provided by Harvard Leppe, Catalina Parra, Lotty University Committee on the Rosenfeld, UNAC (Unión por la Arts. The first iteration, Embodied Cultura), Cecilia Vicuña, and Raúl Absence: Ephemerality and Zurita with Cristóbal Lehyt Collectivity in Chilean Art of the 1970s (September 2015–January Guest curated by Liz Munsell, 2016), was organized by Museo Assistant Curator of Contemporary de la Solidaridad Salvador Art & Special Initiatives, Museum of Fine Allende, Santiago, Chile, with its Arts, Boston, and visiting curator, David substantial support in research Rockefeller Center for Latin American and production of works, in Studies (DRCLAS), Harvard University collaboration with DRCLAS. Embodied Absence Liz Munsell Following the U.S.-backed coup d’état in 1973,1 Chilean artists residing in Santiago and abroad created artworks that spoke to their experience of political, social, and geographic marginalization. Inside the country, they adopted the highly coded languages of conceptual art to evade censorship, exhibited work in public space in lieu of institutional support, and formed independently run galleries and artist collectives to protect their individual identities. Artists abroad staged public events and made artwork in solidarity with those at home. Their exhibitions, performances, interventions, and workshops spread awareness among international audiences and broke down isolating conditions within Chile. -

Vernon Fisher

Vernon Fisher 1943 Born, Fort Worth, TX EDUCATION 1967 BA, Hardin-Simmons University, Abilene, TX 1969 MFA, University of Illinois, Champaign, IL TEACHING 1978-2006 Regents Professor of Art Emeritus, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 1969-1978 Associate Professor of Art, Austin College, Sherman, TX AWARDS 1995 John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship 1992 Distinguished Teaching of Art Award, College Art Association 1988 Awards in the Visual Arts, Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art 1984 Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation 1981-82 National Endowment for the Arts Individual Artist’s Fellowship 1980-81 National Endowment for the Arts Individual Artist’s Fellowship 1974-75 National Endowment for the Arts Individual Artist’s Fellowship 1968-69 University Fellow in Art, University of Illinois 1967-68 University Fellow in Art, University of Illinois SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Distant Voices in a Foreign Language, Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA 2015 Vernon Fisher: 1977–2015, Mark Moore Gallery, Culver City, CA Lifting Weights in Space, Zolla Lieberman Gallery, Chicago, IL 2014 Faces, Hiram Butler Gallery, Houston, TX 2013 The Long Road to Nowhere, Mark Moore Gallery, Culver City, CA Flaubert’s parrot Schrodinger’s cat hey look monkeys throwing shit, Talley Dunn Gallery, Dallas, TX 2011 Vernon Fisher 1989-1999, Dunn and Brown Contemporary, Dallas, TX 2010 K-Mart Conceptualism, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, TX Vernon Fisher, Devin Borden Hiram Butler Gallery, Houston, TX 2009 Dead Reckoning, Dallas Contemporary, Dallas, TX 2008 Descent -

Oral History Interview with Claudia Demonte, 1991 February 13- April 24

Oral history interview with Claudia DeMonte, 1991 February 13- April 24 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Claudia DeMonte on February 13 & 27 and April 24, 1991. The interview took place in College Park, Maryland, and was conducted by Liza Kirwin for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview LIZA KIRWIN: This is Liza Kirwin interviewing Claudia DeMonte for the Archives of American Art, February l3, l99l -- Ash Wednesday -- CLAUDIA DEMONTE: Yes! LIZA KIRWIN: -- a day to think about your immortality and maybe a good day to reflect on the past. I thought we'd just lead off with a question about your childhood. What were some of your early memories? CLAUDIA DEMONTE: I grew up in a very ethnic neighborhood in Queens called Astoria, where my mother still lives, which I love and am very proud of, and I grew up thinking I was rich. If I took you to where I grew up, you'd be shocked that I ever thought that, but we lived in this little apartment building next to an empty lot, next to a huge school building. No one spoke the same language. My grandparents came from Europe and everybody's grandparents there came from Europe and everybody was kind of aiming to become middle class -- Queens is very middle class. -

Oral History Interview with Sam Gilliam, 1989 Nov. 4-11

Oral history interview with Sam Gilliam, 1989 Nov. 4-11 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Sam Gilliam on November 4- 11, 1989. The interview took place in Washington, DC, and was conducted by Benjamin Forgey for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Sam Gilliam and Benjamin Forgey have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview BENJAMIN FORGEY: I feel like a good place to start - I mean, this is as you know, SG, is about Washington. But I thought we could back up a little bit. I'd be interested to know when you were in Louisville getting your graduate degree, how you decided to come to Washington, why you decided Washington, why you moved. SAM GILLIAM: I went to graduate school from 1958 til "61 because I taught during the daytime and went to school part-time. I came to Washington because Dorothy and I had decided to get married. All the time that - if I was in the Army here, she was in school some place else. And finally when I was in school in Louisville she was in school in Columbia, in New York City.