THE CENTENARY of LATVIA's FOREIGN AFFAIRS. Global Thought and Latvia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

Download Download

Ajalooline Ajakiri, 2016, 3/4 (157/158), 477–511 Historical consciousness, personal life experiences and the orientation of Estonian foreign policy toward the West, 1988–1991 Kaarel Piirimäe and Pertti Grönholm ABSTRACT The years 1988 to 1991 were a critical juncture in the history of Estonia. Crucial steps were taken during this time to assure that Estonian foreign policy would not be directed toward the East but primarily toward the integration with the West. In times of uncertainty and institutional flux, strong individuals with ideational power matter the most. This article examines the influence of For- eign Minister Lennart Meri’s and Prime Minister Edgar Savisaar’s experienc- es and historical consciousness on their visions of Estonia’s future position in international affairs. Life stories help understand differences in their horizons of expectation, and their choices in conducting Estonian diplomacy. Keywords: historical imagination, critical junctures, foreign policy analysis, So- viet Union, Baltic states, Lennart Meri Much has been written about the Baltic states’ success in breaking away from Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and their decisive “return to the West”1 via radical economic, social and politi- Research for this article was supported by the “Reimagining Futures in the European North at the End of the Cold War” project which was financed by the Academy of Finland. Funding was also obtained from the “Estonia, the Baltic states and the Collapse of the Soviet Union: New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War” project, financed by the Estonian Research Council, and the “Myths, Cultural Tools and Functions – Historical Narratives in Constructing and Consolidating National Identity in 20th and 21st Century Estonia” project, which was financed by the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies (TIAS, University of Turku). -

Draws YONEX Latvia International 2017

YONEX Latvia International 2017 MS-Qualification Badminton Tournament Planner - bwf.tournamentsoftware.com Member ID St. Cnty Flag Round 1 Round 2 Round 3 Finals Qualifiers 1 61900 CZE Filip Budzel [1] 2 Bye 3 70399 BEL Julien Carraggi 4 Bye 5 65789 FIN Juha Honkanen 6 Bye 7 61426 ISL Eidur Isak Broddason 8 82856 GER Simon Oziminski Q1 9 85443 LTU Povilas Bartusis [12] 10 Bye 11 61897 POL Robert Cybulski 12 Bye 13 77902 LTU Jonas Petkus 14 56849 BLR Dzmitry Saidakou 15 59407 NOR Mattias Xu 16 65678 UKR Ivan Medynskiy 17 95270 ENG Viknesh Rajendran [8] 18 Bye 19 65489 EST Mikk Järveoja 20 Bye 21 64456 SWE Oskar Svensson 22 Bye 23 69084 FIN Miika Lahtinen 24 73926 EST Karl-Rasmus Pungas Q2 25 60261 UKR Vladyslav Volnyanskiy [15] 26 Bye 27 98425 EST Alexander Raudsepp 28 Bye 29 72455 ISL Robert Ingi Huldarsson 30 61739 MAS Ridzwan Rahmat 31 90031 GER Saruul Shafiq 32 97423 EST Mikk Ounmaa 33 69685 ENG Zach Russ [3] 34 Bye 35 89135 LTU Mark Sames 36 Bye 37 78756 LAT Arturs Kelpe 38 Bye 39 61771 IRL Mark Brady 40 84442 LTU Edgaras Slusnys Q3 41 56275 DEN Mads Kjærgaard [16] 42 Bye 43 59413 LTU Karolis Eimutaitis 44 Bye 45 96316 EST Matis Kaart 46 62475 CZE Petr Beran 47 66199 LAT Kristaps Kalnins 48 78891 SUI Nicolas A. Mueller 49 56160 FIN Jesper Paul [7] 50 Bye 51 70534 LAT Janis Vaivads 52 Bye 53 64649 SWE Emil Johansson 54 66853 LTU Ignas Reznikas 55 52290 UKR Valeriy Atrashchenkov 56 76226 LAT Ivo Keiss Q4 57 68484 BLR Vladzislav Kushnir [14] 58 Bye 59 86632 UKR Artem Tkachuk 60 Bye 61 73269 SUI Jonas Schwarz 62 73950 MAS Muhammad Ziyad -

From Tribe to Nation a Brief History of Latvia

From Tribe to Nation A Brief History of Latvia 1 Cover photo: Popular People of Latvia are very proud of their history. It demonstration on is a history of the birth and development of the Dome Square, 1989 idea of an independent nation, and a consequent struggle to attain it, maintain it, and renew it. Above: A Zeppelin above Rīga in 1930 Albeit important, Latvian history is not entirely unique. The changes which swept through the ter- Below: Participants ritory of Latvia over the last two dozen centuries of the XXV Nationwide were tied to the ever changing map of Europe, Song and Dance and the shifting balance of power. From the Viking Celebration in 2013 conquests and German Crusades, to the recent World Wars, the territory of Latvia, strategically lo- cated on the Baltic Sea between the Scandinavian region and Russia, was very much part of these events, and shared their impact especially closely with its Baltic neighbours. What is unique and also attests to the importance of history in Latvia today, is how the growth and development of a nation, initially as a mere idea, permeated all these events through the centuries up to Latvian independence in 1918. In this brief history of Latvia you can read how Latvia grew from tribe to nation, how its history intertwined with changes throughout Europe, and how through them, or perhaps despite them, Lat- via came to be a country with such a proud and distinct national identity 2 1 3 Incredible Historical Landmarks Left: People of The Baltic Way – this was one of the most crea- Latvia united in the tive non-violent protest activities in history. -

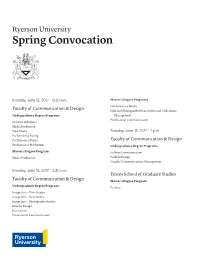

Ryerson University Spring Convocation

Ryerson University Spring Convocation Monday, June 12, 2017 • 9:30 a.m. Master’s Degree Programs Documentary Media Faculty of Communication & Design Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Undergraduate Degree Programs Management Professional Communication Creative Industries Media Production New Media Tuesday, June 13, 2017 • 1 p.m. Performance Acting Performance Dance Faculty of Communication & Design Performance Production Undergraduate Degree Programs Master’s Degree Program Fashion Communication Media Production Fashion Design Graphic Communications Management Monday, June 12, 2017 • 2:30 p.m. Yeates School of Graduate Studies Faculty of Communication & Design Master’s Degree Program Undergraduate Degree Programs Fashion Image Arts – Film Studies Image Arts – New Media Image Arts – Photography Studies Interior Design Journalism Professional Communication Convocation Program Monday, June 12, 2017 • 9:30 a.m. Eagle Staff Carrier Mace Carrier and Bedel Tracey King Cynthia Ashperger Aboriginal Human Resources Consultant Director Ryerson Aboriginal Student Services Acting Program School of Performance Convocation Ceremony Invocation Family and friends are requested to rise when the In the toil of thinking; in the serenity of books; in the academic procession enters, and remain standing until messages of prophets, the songs of poets and the wisdom the conclusion of the invocation. of interpreters; in discoveries of continents of truth whose margins we may see; we delight in free minds and in their Following the convocation address, the graduands will thinking. rise for the general presentation of candidates and then resume their seats. Afterwards, graduands will be called In the majesty of the moral order; in the faith that right and presented for the awarding of certificates, and will triumph; in the courage given us when we ally undergraduate and graduate degrees. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Latvia's 'Russian Left': Trapped Between Ethnic, Socialist, and Social-Democratic Identities

Cheskin, A., and March, L. (2016) Latvia’s ‘Russian left’: trapped between ethnic, socialist, and social-democratic identities. In: March, L. and Keith, D. (eds.) Europe's Radical Left: From Marginality to the Mainstream? Rowman & Littlefield: London, pp. 231-252. ISBN 9781783485352. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/133777/ Deposited on: 11 January 2017 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk This is an author’s final draft. The article has been published as: Cheskin, A. & March, L. (2016) ‘Latvia’s ‘Russian left’: Trapped between ethnic, socialist, and social-democratic identities’ in, L. March & D. Keith (eds.) Europe’s radical left: From marginality to the mainstream? Rowman and Littlefield: London, pp. 231-252. Latvia’s ‘Russian left’: trapped between ethnic, socialist, and social- democratic identities Ammon Cheskin and Luke March Following the 2008 economic crisis, Latvia suffered the worst loss of output in the world, with GDP collapsing 25 percent.1 Yet Latvia’s radical left has shown no notable ideological or strategic response. Existing RLPs did not secure significant political gains from the crisis, nor have new challengers benefitted. Indeed, Latvia has been heralded as a ‘poster child’ for austerity as the right has continued to dominate government policy.2 This chapter explores this puzzle. Although the economic crisis was economically destructive, we argue that the political responses have been consistently ethnicised in Latvia. Additionally, the Latvian left has been equally challenged intellectually and strategically by the ethnically-framed Ukrainian crisis of 2014. -

The Courlander Experience in Tobago

THE COURLANDER EXPERIENCE IN TOBAGO THE REPUBLIC OF LATVIA: A maritime nation on the Baltic sea with excellent ports, 64.589km2 in area and a population of nearly 2.000.000 inhabitants. There are apx. 1.500.000 Latvians living in Latvia and the rest of the world. 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Republic of Latvia. COURLANDERS: Latvians from the province of Courland (Kurzeme). In the days of the Duchy of Courland and Semgallia, a “Courlander” could also be an inhabitant of the province of Semgallia. “Courlander” is a literal translation of the Latvian kurzemnieks. The academic word for anything pertaining to Courland is Couronian. THE DUCHY OF COURLAND AND SEMGALLIA: A de facto independent nation formed in 1561 and existing until 1795, comprised of 2 modern day provinces of Latvia, and ruled by the German-Baltic dukes of Courland, although officially a part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The flags of Courland consisted of a red and white 2 band flag and the red and black “crab” flag which originated in Tobago, as there are no crabs of this type in Latvia. As such, it can be considered the first flag of Tobago. CHRONOLOGY 1639 Sent by Duke Jacob, probably involuntarily, 212 Courlanders arrive in Tobago. Unprepared for tropical conditions, they eventually perish. 1642 (possibly 1640) Duke Jacob engages a Brazilian, capt. Cornelis Caroon (later, Caron) to lead a colony comprised basically of Dutch Zealanders, that probably establishes itself in the flat, southwestern portion of the island. Under attack by the Caribs, 70 remaining members of the original 310 colonists are evacuated to Pomeron, Guyana, by the Arawaks. -

Political Leaders in Africa: Presidents, Patrons Or Profiteers?

Political Leaders in Africa: Presidents, Patrons or Profiteers? By Jo-Ansie van Wyk Occasional Paper Series: Volume 2, Number 1, 2007 The Occasional Paper Series is published by The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD). ACCORD is a non-governmental, non-aligned conflict resolution organisation based in Durban, South Africa. ACCORD is constituted as an education trust. Views expressed in this Occasional Paper are not necessarily those of ACCORD. While every attempt is made to ensure that the information published here is accurate, no responsibility is accepted for any loss or damage that may arise out of the reliance of any person upon any of the information this Occassional Paper contains. Copyright © ACCORD 2007 All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISSN 1608-3954 Unsolicited manuscripts may be submitted to: The Editor, Occasional Paper Series, c/o ACCORD, Private Bag X018, Umhlanga Rocks 4320, Durban, South Africa or email: [email protected] Manuscripts should be about 10 000 words in length. All references must be included. Abstract It is easy to experience a sense of déjà vu when analysing political lead- ership in Africa. The perception is that African leaders rule failed states that have acquired tags such as “corruptocracies”, “chaosocracies” or “terrorocracies”. Perspectives on political leadership in Africa vary from the “criminalisation” of the state to political leadership as “dispensing patrimony”, the “recycling” of elites and the use of state power and resources to consolidate political and economic power. -

The Latvian Institute of International Affairs (LIIA)

The Latvian Institute of International Affairs (LIIA) was established in May 1992 in Riga as a non-profit foundation charged with the aim of providing Latvia’s decision-makers, experts and the wider public with analysis, recommendations and information about international developments, regional security issues and foreign policy strategies and choices, and performing scientific research. It is an independent think-tank that conducts research, develops publications and organizes public lectures and international conferences related to global affairs and Latvia’s international role and policies. Among Latvian think tanks, the LIIA is the oldest and one of the most well-known and internationally recognized institutions, especially as the leading think tank that specializes in international affairs. In the LIIA's efforts to provide expertise from a Latvian perspective, the Institute and its fellows have participated in and coordinated various international research projects. The Institute has recently been focusing on such research themes as • Latvian foreign policy • Transatlantic relations • European Union institutional and financial developments and foreign policy positioning • Russia and its relations with its neighbours The LIIA has also devoted thorough attention to various aspects of energy security and policies: • EU energy policy, • EU-Russia energy dialogue, • national and regional (Central and East Europe, Baltic Sea region, post-Soviet space) energy interaction. The LIIA was founded and initially funded by several grants from the Swedish government to support research on Baltic security, and has cooperated with the Swedish Institute of International Affairs in skills transfer programmes for a number of years. The LIIA is currently financed by individual projects and does not receive permanent funding from any governmental or other non-governmental institutions. -

Latvia Towards Europe: Internal Security Issues

North Atlantic Treaty Organization Andris Runcis LATVIA TOWARDS EUROPE: INTERNAL SECURITY ISSUES Final Report The preparation of this Report was made possible through a NATO Award. Rîga, 1999 1 Content Introduction 3 1. The basic aspects of a country’s security 5 2. Latvia’s security concept 8 3. Corruption 10 4. Unemployment 17 5. Non-governmental organizations 19 6. The Latvian banking system and its crisis 27 7. Citizenship issue 32 Conclusion 46 Appendix 48 2 Introduction The security of small countries has been a difficult problem since ancient times. Now, when the Cold War has ended and Europe has moved from a bipolar to a multipolar system, when the communist system in Eastern Europe has collapsed and the Soviet empire has disintegrated – processes which have led to the appearance of a series of new and mostly small countries in Europe – we are witnessing a renaissance of small countries in the international arena. Since regaining independence Latvia’s general foreign policy orientation has been associated with integration into European economic, political and military structures where full membership in the European Union (EU) is the cornerstone. The issue has been one of the most consolidated and undisputed on the country’s political agenda. Latvian politicians have stressed the country’s wish to become a member state of the European Union. On October 14, 1995, all political parties represented in the Parliament supported the State President’s proposed Declaration on the Policy of Latvian Integration in the European Union. On October 27, Latvia submitted its application for membership to the EU. -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2018 XXIV

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEARBOOK FACTS AND FIGURES ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XXIV (51) 2018 TALLINN 2019 This book was compiled by: Jaak Järv (editor-in-chief) Editorial team: Siiri Jakobson, Ebe Pilt, Marika Pärn, Tiina Rahkama, Ülle Raud, Ülle Sirk Translator: Kaija Viitpoom Layout: Erje Hakman Photos: Annika Haas p. 30, 31, 48, Reti Kokk p. 12, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47, 49, 52, 53, Janis Salins p. 33. The rest of the photos are from the archive of the Academy. Thanks to all authos for their contributions: Jaak Aaviksoo, Agnes Aljas, Madis Arukask, Villem Aruoja, Toomas Asser, Jüri Engelbrecht, Arvi Hamburg, Sirje Helme, Marin Jänes, Jelena Kallas, Marko Kass, Meelis Kitsing, Mati Koppel, Kerri Kotta, Urmas Kõljalg, Jakob Kübarsepp, Maris Laan, Marju Luts-Sootak, Märt Läänemets, Olga Mazina, Killu Mei, Andres Metspalu, Leo Mõtus, Peeter Müürsepp, Ülo Niine, Jüri Plado, Katre Pärn, Anu Reinart, Kaido Reivelt, Andrus Ristkok, Ave Soeorg, Tarmo Soomere, Külliki Steinberg, Evelin Tamm, Urmas Tartes, Jaana Tõnisson, Marja Unt, Tiit Vaasma, Rein Vaikmäe, Urmas Varblane, Eero Vasar Printed in Priting House Paar ISSN 1406-1503 (printed version) © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA ISSN 2674-2446 (web version) CONTENTS FOREWORD ...........................................................................................................................................5 CHRONICLE 2018 ..................................................................................................................................7 MEMBERSHIP