Morphology and Morphogenesis of the Seed Cones of the Cupressaceae - Part III Callitroideae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thuja Plicata Has Many Traditional Uses, from the Manufacture of Rope to Waterproof Hats, Nappies and Other Kinds of Clothing

photograph © Daniel Mosquin Culturally modified tree. The bark of Thuja plicata has many traditional uses, from the manufacture of rope to waterproof hats, nappies and other kinds of clothing. Careful, modest, bark stripping has little effect on the health or longevity of trees. (see pages 24 to 35) photograph © Douglas Justice 24 Tree of the Year : Thuja plicata Donn ex D. Don In this year’s Tree of the Year article DOUGLAS JUSTICE writes an account of the western red-cedar or giant arborvitae (tree of life), a species of conifers that, for centuries has been central to the lives of people of the Northwest Coast of America. “In a small clearing in the forest, a young woman is in labour. Two women companions urge her to pull hard on the cedar bark rope tied to a nearby tree. The baby, born onto a newly made cedar bark mat, cries its arrival into the Northwest Coast world. Its cradle of firmly woven cedar root, with a mattress and covering of soft-shredded cedar bark, is ready. The young woman’s husband and his uncle are on the sea in a canoe carved from a single red-cedar log and are using paddles made from knot-free yellow cedar. When they reach the fishing ground that belongs to their family, the men set out a net of cedar bark twine weighted along one edge by stones lashed to it with strong, flexible cedar withes. Cedar wood floats support the net’s upper edge. Wearing a cedar bark hat, cape and skirt to protect her from the rain and INTERNATIONAL DENDROLOGY SOCIETY TREES Opposite, A grove of 80- to 100-year-old Thuja plicata in Queen Elizabeth Park, Vancouver. -

Messinian Vegetation and Climate of the Intermontane Florina-Ptolemais

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/848747; this version posted November 25, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 Messinian vegetation and climate of the intermontane Florina-Ptolemais-Servia Basin, 2 NW Greece inferred from palaeobotanical data: How well do plant fossils reflect past 3 environments? 4 5 Johannes M. Bouchal1*, Tuncay H. Güner2, Dimitrios Velitzelos3, Evangelos Velitzelos3, 6 Thomas Denk1 7 8 1Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Palaeobiology, Box 50007, 10405 9 Stockholm, Sweden 10 2Faculty of Forestry, Department of Forest Botany, Istanbul University Cerrahpaşa, Istanbul, 11 Turkey 12 3National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Faculty of Geology and Geoenvironment, 13 Section of Historical Geology and Palaeontology, Greece 14 15 16 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/848747; this version posted November 25, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 17 The late Miocene is marked by pronounced environmental changes and the appearance of 18 strong temperature and precipitation seasonality. Although environmental heterogeneity is to 19 be expected during this time, it is challenging to reconstruct palaeoenvironments using plant 20 fossils. We investigated leaves and dispersed spores/pollen from 6.4–6 Ma strata in the 21 intermontane Florina-Ptolemais-Servia Basin (FPS) of NW Greece. -

Cinara Cupressivora W Atson & Voegtlin, 1999 Other Scientific Names: Order and Family: Hemiptera: Aphididae Common Names: Giant Cypress Aphid; Cypress Aphid

O R E ST E ST PE C IE S R O FIL E F P S P November 2007 Cinara cupressivora W atson & Voegtlin, 1999 Other scientific names: Order and Family: Hemiptera: Aphididae Common names: giant cypress aphid; cypress aphid Cinara cupressivora is a significant pest of Cupressaceae species and has caused serious damage to naturally regenerating and planted forests in Africa, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean and the Near East. It is believed to have originated on Cupressus sempervirens from eastern Greece to just south of the Caspian Sea (Watson et al., 1999). This pest has been recognized as a separate species for only a short time (Watson et al., 1999) and much of the information on its biology and ecology has been reported under the name Cinara cupressi. Cypress aphids (Photos: Bugwood.org – W .M . Ciesla, Forest Health M anagement International (left, centre); J.D. W ard, USDA Forest Service (right)) DISTRIBUTION Native: eastern Greece to just south of the Caspian Sea Introduced: Africa: Burundi (1988), Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia (2004), Kenya (1990), Malawi (1986), Mauritius (1999), Morocco, Rwanda (1989), South Africa (1993), Uganda (1989), United Republic of Tanzania (1988), Zambia (1985), Zimbabwe (1989) Europe: France, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom Latin America and Caribbean: Chile (2003), Colombia Near East: Jordan, Syria, Turkey, Yemen IDENTIFICATION Giant conifer aphid adults are typically 2-5 mm in length, dark brown in colour with long legs (Ciesla, 2003a). Their bodies are sometimes covered with a powdery wax. They typically occur in colonies of 20-80 adults and nymphs on the branches of host trees (Ciesla, 1991). -

New Fossil Plant Discovery Links Patagonia to New Guinea in a Warmer Past 10 November 2009

New fossil plant discovery links Patagonia to New Guinea in a warmer past 10 November 2009 insect-feeding richness found at the fossil sites. The specimen shown is coalified with light patches of facial leaf cuticle visible overlying coal. Note opposite branching, enlarged lateral leaves, and light-colored amber in foliar resin canals. Credit: Image credit: P. Wilf. Fossil plants are windows to the past, providing us with clues as to what our planet looked like millions of years ago. Not only do fossils tell us which species were present before human-recorded history, but they can provide information about the climate and how and when lineages may have dispersed around the world. Identifying fossil plants can be tricky, however, when plant organs fail to be This is foliage of Papuacedrus prechilensis (Berry) Wilf preserved or when only a few sparse parts can be et al., comb. nov. (Cupressaceae), from the middle found. Eocene Río Pichileufú flora of Río Negro Province, Patagonia, Argentina. The monotypic genus In the November issue of the American Journal of Papuacedrus is today restricted to montane rainforests Botany, Peter Wilf (of Pennsylvania State of New Guinea and the Moluccas, but its scarce fossil University) and his U.S. and Argentine colleagues record includes Tasmania and Antarctica. Wilf et al. published their recent discovery of abundant describe a suite of well-preserved specimens excavated from early and middle Eocene sites in Patagonia, fossilized specimens of a conifer previously known including an immature seed cone attached to foliage with as "Libocedrus" prechilensis found in Argentinean organic preservation, bearing numerous characters Patagonia. -

Contributions to the Life-History of Tetraclinis Articu- Lata, Masters, with Some Notes on the Phylogeny of the Cupressoideae and Callitroideae

Contributions to the Life-history of Tetraclinis articu- lata, Masters, with some Notes on the Phylogeny of the Cupressoideae and Callitroideae. BY W. T. SAXTON, M.A., F.L.S., Professor of Botany at the Ahmedabad Institute of Science, India. With Plates XLIV-XLVI and nine Figures in the Text. INTRODUCTION. HE Gum Sandarach tree of Morocco and Algeria has been well known T to botanists from very early times. Some account of it is given by Hooker and Ball (20), who speak of the beauty and durability of the wood, and state that they consider the tree to be probably correctly identified with the Bvlov of the Odyssey (v. 60),1 and with the Ovlov and Ovia of Theo- phrastus (' Hist. PI.' v. 3, 7)/ as well as, undoubtedly, with the Citrus wood of the Romans. The largest trees met with by them, growing in an un- cultivated state, were about 30 feet high. The resin, known as sandarach, is stated to be collected by the Moors and exported to Europe, where it is used as a varnish. They quote Shaw (49 a and b) as having described and figured the tree under the name of Thuja articulata, in his ' Travels in Barbary'; this statement, however, is not accurate. In both editions of the work cited the plant is figured and described as ' Cupressus fructu quadri- valvi, foliis Equiseti instar articulatis '. Some interesting particulars of the use of the timber are given by Hansen (19), who also implies that the embryo has from three to six cotyledons. Both Hooker and Ball, and Hansen, followed by almost all others who have studied the plant, speak of it as Callitris qtiadrivalvis. -

Extinction, Transoceanic Dispersal, Adaptation and Rediversification

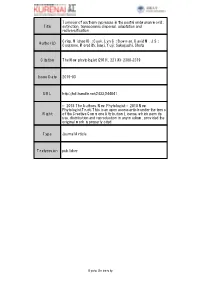

Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: Title extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Crisp, Michael D.; Cook, Lyn G.; Bowman, David M. J. S.; Author(s) Cosgrove, Meredith; Isagi, Yuji; Sakaguchi, Shota Citation The New phytologist (2019), 221(4): 2308-2319 Issue Date 2019-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/244041 © 2018 The Authors. New Phytologist © 2018 New Phytologist Trust; This is an open access article under the terms Right of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Research Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Michael D. Crisp1 , Lyn G. Cook2 , David M. J. S. Bowman3 , Meredith Cosgrove1, Yuji Isagi4 and Shota Sakaguchi5 1Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, RN Robertson Building, 46 Sullivans Creek Road, Acton (Canberra), ACT 2601, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072, Australia; 3School of Natural Sciences, The University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart, Tas 7001, Australia; 4Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan; 5Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan Summary Author for correspondence: Cupressaceae subfamily Callitroideae has been an important exemplar for vicariance bio- Michael D. Crisp geography, but its history is more than just disjunctions resulting from continental drift. We Tel: +61 2 6125 2882 combine fossil and molecular data to better assess its extinction and, sometimes, rediversifica- Email: [email protected] tion after past global change. -

Chile: a Journey to the End of the World in Search of Temperate Rainforest Giants

Eliot Barden Kew Diploma Course 53 July 2017 Chile: A Journey to the end of the world in search of Temperate Rainforest Giants Valdivian Rainforest at Alerce Andino Author May 2017 1 Eliot Barden Kew Diploma Course 53 July 2017 Table of Contents 1. Title Page 2. Contents 3. Table of Figures/Introduction 4. Introduction Continued 5. Introduction Continued 6. Aims 7. Aims Continued / Itinerary 8. Itinerary Continued / Objective / the Santiago Metropolitan Park 9. The Santiago Metropolitan Park Continued 10. The Santiago Metropolitan Park Continued 11. Jardín Botánico Chagual / Jardin Botanico Nacional, Viña del Mar 12. Jardin Botanico Nacional Viña del Mar Continued 13. Jardin Botanico Nacional Viña del Mar Continued 14. Jardin Botanico Nacional Viña del Mar Continued / La Campana National Park 15. La Campana National Park Continued / Huilo Huilo Biological Reserve Valdivian Temperate Rainforest 16. Huilo Huilo Biological Reserve Valdivian Temperate Rainforest Continued 17. Huilo Huilo Biological Reserve Valdivian Temperate Rainforest Continued 18. Huilo Huilo Biological Reserve Valdivian Temperate Rainforest Continued / Volcano Osorno 19. Volcano Osorno Continued / Vicente Perez Rosales National Park 20. Vicente Perez Rosales National Park Continued / Alerce Andino National Park 21. Alerce Andino National Park Continued 22. Francisco Coloane Marine Park 23. Francisco Coloane Marine Park Continued 24. Francisco Coloane Marine Park Continued / Outcomes 25. Expenditure / Thank you 2 Eliot Barden Kew Diploma Course 53 July 2017 Table of Figures Figure 1.) Valdivian Temperate Rainforest Alerce Andino [Photograph; Author] May (2017) Figure 2. Map of National parks of Chile Figure 3. Map of Chile Figure 4. Santiago Metropolitan Park [Photograph; Author] May (2017) Figure 5. -

Nuclear and Cytoplasmic DNA Sequence Data Further Illuminate the Genetic Composition of Leyland Cypresses

J. AMER.SOC.HORT.SCI. 139(5):558–566. 2014. Nuclear and Cytoplasmic DNA Sequence Data Further Illuminate the Genetic Composition of Leyland Cypresses Yi-Xuan Kou1 MOE Key Laboratory of Bio-Resources and Eco-Environment, College of Life Science, Sichuan University, 29 Wangjiang Road, Chengdu 610064, China Hui-Ying Shang1 State Key Laboratory of Grassland Agro-Ecosystem, School of Life Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, China Kang-Shan Mao2 MOE Key Laboratory of Bio-Resources and Eco-Environment, College of Life Science, Sichuan University, 29 Wangjiang Road, Chengdu 610064, China Zhong-Hu Li College of Life Sciences, Northwest University, Xi’an 710069, China Keith Rushforth The Shippen, Ashill, Cullompton, Devon, EX15 3NL, U.K. Robert P. Adams Biology Department, Baylor University, P.O. Box 97388, Waco, TX 76798 ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. alaska cypress, Callitropsis nootkatensis, Hesperocyparis macrocarpa, ·Hesperotropsis leylandii, hybridization, internal transcribed spacer, ITS, leafy, monterey cypress, molecular identification, needly ABSTRACT. Leyland cypress [·Hesperotropsis leylandii (A.B. Jacks. & Dallim.) Garland & G. Moore, Cupressaceae] is a well-known horticultural evergreen conifer in the United Kingdom, United States, Australia, New Zealand, and other countries. As demonstrated by previous studies, this taxon is a hybrid between alaska (nootka) cypress [Callitropsis nootkatensis (D. Don) Oerst. ex D.P. Little] and monterey cypress [Hesperocyparis macrocarpa (Hartw. ex Gordon) Bartel]. However, the genetic background of leyland cypress cultivars is unclear. Are they F1 or F2 hybrids or backcrosses? In this study, six individuals that represent major leyland cypress cultivars and two individuals each of its two putative parental species were collected, and three nuclear DNA regions (internal transcribed spacer, leafy and needly), three mitochondrial (mt) DNA regions (coxI, atpA, and rps3), and two chloroplast (cp) DNA regions (matKand rbcL) were sequenced and analyzed. -

Callitris Forests and Woodlands

NVIS Fact sheet MVG 7 – Callitris forests and woodlands Australia’s native vegetation is a rich and fundamental Overview element of our natural heritage. It binds and nourishes our ancient soils; shelters and sustains wildlife, protects Typically, vegetation areas classified under MVG 7 – streams, wetlands, estuaries, and coastlines; and absorbs Callitris forests and woodlands: carbon dioxide while emitting oxygen. The National • comprise pure stands of Callitris that are restricted and Vegetation Information System (NVIS) has been developed generally occur in the semi-arid regions of Australia and maintained by all Australian governments to provide • in most cases Callitris species are a co-dominant a national picture that captures and explains the broad or occasional species in other vegetation groups, diversity of our native vegetation. particularly eucalypt woodlands and forests in temperate This is part of a series of fact sheets which the Australian semi-arid and sub-humid climates. After disturbance, Government developed based on NVIS Version 4.2 data to Callitris may regenerate in high densities and become provide detailed descriptions of the major vegetation groups a dominant member of a mixed canopy layer. Some of (MVGs) and other MVG types. The series is comprised of these modified communities are mapped asCallitris a fact sheet for each of the 25 MVGs to inform their use by forests or woodlands planners and policy makers. An additional eight MVGs are • are generally dominated by a herbaceous understorey available outlining other MVG types. with only a few shrubs • in New South Wales Callitris has been an important For more information on these fact sheets, including forestry timber and large monocultures have been its limitations and caveats related to its use, please see: encouraged for this purpose ‘Introduction to the Major Vegetation Group (MVG) fact sheets’. -

Cupressaceae Calocedrus Decurrens Incense Cedar

Cupressaceae Calocedrus decurrens incense cedar Sight ID characteristics • scale leaves lustrous, decurrent, much longer than wide • laterals nearly enclosing facials • seed cone with 3 pairs of scale/bract and one central 11 NOTES AND SKETCHES 12 Cupressaceae Chamaecyparis lawsoniana Port Orford cedar Sight ID characteristics • scale leaves with glaucous bloom • tips of laterals on older stems diverging from branch (not always too obvious) • prominent white “x” pattern on underside of branchlets • globose seed cones with 6-8 peltate cone scales – no boss on apophysis 13 NOTES AND SKETCHES 14 Cupressaceae Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic white cedar Sight ID characteristics • branchlets slender, irregularly arranged (not in flattened sprays). • scale leaves blue-green with white margins, glandular on back • laterals with pointed, spreading tips, facials closely appressed • bark fibrous, ash-gray • globose seed cones 1/4, 4-5 scales, apophysis armed with central boss, blue/purple and glaucous when young, maturing in fall to red-brown 15 NOTES AND SKETCHES 16 Cupressaceae Callitropsis nootkatensis Alaska yellow cedar Sight ID characteristics • branchlets very droopy • scale leaves more or less glabrous – little glaucescence • globose seed cones with 6-8 peltate cone scales – prominent boss on apophysis • tips of laterals tightly appressed to stem (mostly) – even on older foliage (not always the best character!) 15 NOTES AND SKETCHES 16 Cupressaceae Taxodium distichum bald cypress Sight ID characteristics • buttressed trunks and knees • leaves -

Morphology and Morphogenesis of the Seed Cones of the Cupressaceae - Part II Cupressoideae

1 2 Bull. CCP 4 (2): 51-78. (10.2015) A. Jagel & V.M. Dörken Morphology and morphogenesis of the seed cones of the Cupressaceae - part II Cupressoideae Summary The cone morphology of the Cupressoideae genera Calocedrus, Thuja, Thujopsis, Chamaecyparis, Fokienia, Platycladus, Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Cupressus and Juniperus are presented in young stages, at pollination time as well as at maturity. Typical cone diagrams were drawn for each genus. In contrast to the taxodiaceous Cupressaceae, in Cupressoideae outgrowths of the seed-scale do not exist; the seed scale is completely reduced to the ovules, inserted in the axil of the cone scale. The cone scale represents the bract scale and is not a bract- /seed scale complex as is often postulated. Especially within the strongly derived groups of the Cupressoideae an increased number of ovules and the appearance of more than one row of ovules occurs. The ovules in a row develop centripetally. Each row represents one of ascending accessory shoots. Within a cone the ovules develop from proximal to distal. Within the Cupressoideae a distinct tendency can be observed shifting the fertile zone in distal parts of the cone by reducing sterile elements. In some of the most derived taxa the ovules are no longer (only) inserted axillary, but (additionally) terminal at the end of the cone axis or they alternate to the terminal cone scales (Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Juniperus). Such non-axillary ovules could be regarded as derived from axillary ones (Microbiota) or they develop directly from the apical meristem and represent elements of a terminal short-shoot (Tetraclinis, Juniperus). -

Actualización De La Clasificación De Tipos Forestales Y Cobertura Del Suelo De La Región Bosque Andino Patagónico

ACTUALIZACIÓN DE LA CLASIFICACIÓN DE TIPOS FORESTALES Y COBERTURA DEL SUELO DE LA REGIÓN BOSQUE ANDINO PATAGÓNICO INFORME FINAL Julio 2016 CARTOGRAFÍA PARA EL INVENTARIO FORESTAL NACIONAL DE BOSQUES NATIVOS Mapa base para un sistema de monitoreo continuo de la región Información de base 2013 - 2014 Cita recomendada de esta versión del trabajo: CIEFAP, MAyDS, 2016. Actualización de la Clasificación de Tipos Forestales y Cobertura del Suelo de la Región Bosque Andino Patagónico. Informe Final. CIEFAP. https://drive.google.com/open?id=0BxfNQUtfxxeaUHNCQm9lYmk5RnM 2 Presidente de la Nación Ing. Mauricio Macri Ministro de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable de la Nación Rabino Sergio Alejandro Bergman Secretario de Política Ambiental, Cambio Climático y Desarrollo Sustentable Lic. Diego Moreno Sub Secretaria de Planificación y Ordenamiento del Territorio Dra. Dolores Duverges Directora Nacional de Bosques, Ordenamiento Territorial y Suelos Dra. María Esperanza Alonso Director de Bosques Ing. Rubén Manfredi 3 Dirección General de Recursos Forestales de la Provincia de Neuquén Téc. Ftal. Uriel Mele Subsecretaría de Recursos Forestales de la Provincia de Río Negro Ing. Marcelo Perdomo Subsecretaría de Bosques de la Provincia del Chubut Sr. Leonardo Aquilanti Dirección de Bosques de la Provincia de Santa Cruz Ing. Julia Chazarreta Dirección General de Bosques Secretaría de Ambiente, Desarrollo Sustentable y Cambio Climático Provincia de Tierra del Fuego, Antártida e Islas del Atlántico Sur Ing. Gustavo Cortés Administración Parques Nacionales Sr. Eugenio Breard 4 Este trabajo fue realizado por el Nodo Regional Bosque Andino Patagónico (BAP) con la participación de las jurisdicciones regionales. El Nodo BAP tiene sede en el Centro de Investigación y Extensión Forestal Andino Patagónico (CIEFAP) Durante la ejecución de este proyecto, lamentablemente nos dejó de manera trágica nuestro amigo y compañero de trabajo, Ing.