Contributions to the Life-History of Tetraclinis Articu- Lata, Masters, with Some Notes on the Phylogeny of the Cupressoideae and Callitroideae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinara Cupressivora W Atson & Voegtlin, 1999 Other Scientific Names: Order and Family: Hemiptera: Aphididae Common Names: Giant Cypress Aphid; Cypress Aphid

O R E ST E ST PE C IE S R O FIL E F P S P November 2007 Cinara cupressivora W atson & Voegtlin, 1999 Other scientific names: Order and Family: Hemiptera: Aphididae Common names: giant cypress aphid; cypress aphid Cinara cupressivora is a significant pest of Cupressaceae species and has caused serious damage to naturally regenerating and planted forests in Africa, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean and the Near East. It is believed to have originated on Cupressus sempervirens from eastern Greece to just south of the Caspian Sea (Watson et al., 1999). This pest has been recognized as a separate species for only a short time (Watson et al., 1999) and much of the information on its biology and ecology has been reported under the name Cinara cupressi. Cypress aphids (Photos: Bugwood.org – W .M . Ciesla, Forest Health M anagement International (left, centre); J.D. W ard, USDA Forest Service (right)) DISTRIBUTION Native: eastern Greece to just south of the Caspian Sea Introduced: Africa: Burundi (1988), Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia (2004), Kenya (1990), Malawi (1986), Mauritius (1999), Morocco, Rwanda (1989), South Africa (1993), Uganda (1989), United Republic of Tanzania (1988), Zambia (1985), Zimbabwe (1989) Europe: France, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom Latin America and Caribbean: Chile (2003), Colombia Near East: Jordan, Syria, Turkey, Yemen IDENTIFICATION Giant conifer aphid adults are typically 2-5 mm in length, dark brown in colour with long legs (Ciesla, 2003a). Their bodies are sometimes covered with a powdery wax. They typically occur in colonies of 20-80 adults and nymphs on the branches of host trees (Ciesla, 1991). -

Extinction, Transoceanic Dispersal, Adaptation and Rediversification

Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: Title extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Crisp, Michael D.; Cook, Lyn G.; Bowman, David M. J. S.; Author(s) Cosgrove, Meredith; Isagi, Yuji; Sakaguchi, Shota Citation The New phytologist (2019), 221(4): 2308-2319 Issue Date 2019-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/244041 © 2018 The Authors. New Phytologist © 2018 New Phytologist Trust; This is an open access article under the terms Right of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Research Turnover of southern cypresses in the post-Gondwanan world: extinction, transoceanic dispersal, adaptation and rediversification Michael D. Crisp1 , Lyn G. Cook2 , David M. J. S. Bowman3 , Meredith Cosgrove1, Yuji Isagi4 and Shota Sakaguchi5 1Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, RN Robertson Building, 46 Sullivans Creek Road, Acton (Canberra), ACT 2601, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072, Australia; 3School of Natural Sciences, The University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart, Tas 7001, Australia; 4Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan; 5Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan Summary Author for correspondence: Cupressaceae subfamily Callitroideae has been an important exemplar for vicariance bio- Michael D. Crisp geography, but its history is more than just disjunctions resulting from continental drift. We Tel: +61 2 6125 2882 combine fossil and molecular data to better assess its extinction and, sometimes, rediversifica- Email: [email protected] tion after past global change. -

Seiridium Canker of Cypress Trees in Arizona Jeff Schalau

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION AZ1557 January 2012 Seiridium Canker of Cypress Trees in Arizona Jeff Schalau Introduction Leyland cypress (x Cupressocyparis leylandii) is a fast- growing evergreen that has been widely planted as a landscape specimen and along boundaries to create windbreaks or privacy screening in Arizona. The presence of Seiridium canker was confirmed in Prescott, Arizona in July 2011 and it is suspected that the disease occurs in other areas of the state. Seiridium canker was first identified in California’s San Joaquin Valley in 1928. Today, it can be found in Europe, Asia, New Zealand, Australia, South America and Africa on plants in the cypress family (Cupressaceae). Leyland cypress, Monterey cypress, (Cupressus macrocarpa) and Italian cypress (C. sempervirens) are highly susceptible and can be severely impacted by this disease. Since Leyland and Italian cypress have been widely planted in Arizona, it is imperative that Seiridium canker management strategies be applied and suitable resistant tree species be recommended for planting in the future. The Pathogen Seiridium canker is known to be caused by three different fungal species: Seiridium cardinale, S. cupressi and S. unicorne. S. cardinale is the most damaging of the three species and is SCHALAU found in California. S. unicorne and S. cupressi are found in the southeastern United States where the primary host is JEFF Leyland cypress. All three species produce asexual fruiting Figure 1. Leyland cypress tree with dead branch (upper left) and main leader bodies (acervuli) in cankers. The acervuli produce spores caused by Seiridium canker. (conidia) which spread by water, human activity (pruning and transport of infected plant material), and potentially insects, birds and animals to neighboring trees where new Symptoms and Signs infections can occur. -

Management of Threatened, High Conservation Value, Forest Hotspots Under Changing Fire Regimes

Chapter 11 Management of Threatened, High Conservation Value, Forest Hotspots Under Changing Fire Regimes Margarita Arianoutsou , Vittorio Leone , Daniel Moya , Raffaella Lovreglio , Pinelopi Delipetrou , and Jorge de las Heras 11.1 The Biodiversity Hotspots of the Earth Biodiversity hotspots are geographic areas that have high levels of species diversity but signifi cant habitat loss. The term was coined by Norman Myers to indicate areas of the globe which should be a conservation priority (Myers 1988 ) . A biodiversity hotspot can therefore be defi ned as a region with a high proportion of endemic species that has already lost a signifi cant part of its geographic original extent. Each hotspot is a biogeographic unit and features specifi c biota or communities. The current tally includes 34 hotspots (Fig. 11.1 ) where over half of the plant species and 42% of terrestrial vertebrate species are endemic. Such hotspots account for more than 60% of the world’s known plant, bird, mammal, reptile, and amphibian M. Arianoutsou (*) Department of Ecology and Systematics, Faculty of Biology, School of Sciences , National and Kapodistrian University of Athens , Athens , Greece e-mail: [email protected] V. Leone Faculty of Agriculture , University of Basilicata , Potenza , Italy e-mail: [email protected] D. Moya • J. de las Heras ETSI Agronomos, University of Castilla-La Mancha , Albacete , Spain e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] R. Lovreglio Faculty of Agriculture , University of Sassari , Sardinia , Italy e-mail: [email protected] P. Delipetrou Department of Botany, Faculty of Biology , School of Sciences, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens , Athens , Greece e-mail: [email protected] F. -

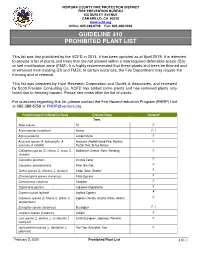

Guideline 410 Prohibited Plant List

VENTURA COUNTY FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT FIRE PREVENTION BUREAU 165 DURLEY AVENUE CAMARILLO, CA 93010 www.vcfd.org Office: 805-389-9738 Fax: 805-388-4356 GUIDELINE 410 PROHIBITED PLANT LIST This list was first published by the VCFD in 2014. It has been updated as of April 2019. It is intended to provide a list of plants and trees that are not allowed within a new required defensible space (DS) or fuel modification zone (FMZ). It is highly recommended that these plants and trees be thinned and or removed from existing DS and FMZs. In certain instances, the Fire Department may require the thinning and or removal. This list was prepared by Hunt Research Corporation and Dudek & Associates, and reviewed by Scott Franklin Consulting Co, VCFD has added some plants and has removed plants only listed due to freezing hazard. Please see notes after the list of plants. For questions regarding this list, please contact the Fire Hazard reduction Program (FHRP) Unit at 085-389-9759 or [email protected] Prohibited plant list:Botanical Name Common Name Comment* Trees Abies species Fir F Acacia species (numerous) Acacia F, I Agonis juniperina Juniper Myrtle F Araucaria species (A. heterophylla, A. Araucaria (Norfolk Island Pine, Monkey F araucana, A. bidwillii) Puzzle Tree, Bunya Bunya) Callistemon species (C. citrinus, C. rosea, C. Bottlebrush (Lemon, Rose, Weeping) F viminalis) Calocedrus decurrens Incense Cedar F Casuarina cunninghamiana River She-Oak F Cedrus species (C. atlantica, C. deodara) Cedar (Atlas, Deodar) F Chamaecyparis species (numerous) False Cypress F Cinnamomum camphora Camphor F Cryptomeria japonica Japanese Cryptomeria F Cupressocyparis leylandii Leyland Cypress F Cupressus species (C. -

Mants Availability Shrubs

FooterDate Co ProdCategory BotPlant A2 Price1 Price2 Price3 Perennials 1 to 24 25 to 49 50 & Up Achellia fillipendulina 'Coronation Gold' 1 Gal 286.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Achellia fillipendulina 'Coronation Gold' Flat 54.00 26.00 23.00 20.00 Achillea millefolium 'Strawberry Seduction' 1 Gal 10.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Andropogon ternarius 1 Gal 1,422.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Asclepias tuberosa 1 Gal 473.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Asclepias tuberosa Flat 30.00 26.00 23.00 20.00 Aster novae-angliae 'Purple Dome' 1 Gal 1,314.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Aster novae-angliae 'Purple Dome' Flat 34.00 26.00 23.00 20.00 Athyrium 'Ghost' 1 Gal 368.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Calamagrostis sp. 1 Gal 242.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Calamagrostis x acutiflora 'Karl Foerester' 3 Gal 598.00 10.75 9.50 8.25 Carex comans Marginata 'Snowline' 1 Gal 898.00 6.25 5.50 4.75 Carex hachijoensis 'Evergold' 1 Gal 926.00 6.25 5.50 4.75 Carex morrovii 'Ice Dance' 1 Gal 1,197.00 6.25 5.50 4.75 Carex pensylvanica 1 Gal 91.00 6.25 5.50 4.75 Chasmanthium latifolium 1 Gal 1,550.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Convallaria majalis 1 Gal 17.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Coreopsis 'Moonbeam' 1 Gal 1,326.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Crocosmia x crocosmiiflora 'Emily McKenzie' 1 Gal 10.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Dicentra spectabilis 3 Gal 21.00 13.50 12.00 10.00 Dryopteris marginalis 1 Gal 854.00 5.50 4.75 4.00 Echinacea 'Pow Wow White' 1 Gal 220.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Echinacea 'Pow wow Wild Berry' 1 Gal 1,920.00 5.00 4.25 3.50 Echinacea 'Pow wow Wild Berry' 2 Gal 72.00 8.50 7.25 6.00 Echinacea 'Pow wow Wild Berry' Flat 9.00 26.00 23.00 20.00 Echinacea purpurea 1 Gal 125.00 5.00 -

Morphology and Morphogenesis of the Seed Cones of the Cupressaceae - Part II Cupressoideae

1 2 Bull. CCP 4 (2): 51-78. (10.2015) A. Jagel & V.M. Dörken Morphology and morphogenesis of the seed cones of the Cupressaceae - part II Cupressoideae Summary The cone morphology of the Cupressoideae genera Calocedrus, Thuja, Thujopsis, Chamaecyparis, Fokienia, Platycladus, Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Cupressus and Juniperus are presented in young stages, at pollination time as well as at maturity. Typical cone diagrams were drawn for each genus. In contrast to the taxodiaceous Cupressaceae, in Cupressoideae outgrowths of the seed-scale do not exist; the seed scale is completely reduced to the ovules, inserted in the axil of the cone scale. The cone scale represents the bract scale and is not a bract- /seed scale complex as is often postulated. Especially within the strongly derived groups of the Cupressoideae an increased number of ovules and the appearance of more than one row of ovules occurs. The ovules in a row develop centripetally. Each row represents one of ascending accessory shoots. Within a cone the ovules develop from proximal to distal. Within the Cupressoideae a distinct tendency can be observed shifting the fertile zone in distal parts of the cone by reducing sterile elements. In some of the most derived taxa the ovules are no longer (only) inserted axillary, but (additionally) terminal at the end of the cone axis or they alternate to the terminal cone scales (Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Juniperus). Such non-axillary ovules could be regarded as derived from axillary ones (Microbiota) or they develop directly from the apical meristem and represent elements of a terminal short-shoot (Tetraclinis, Juniperus). -

Botanic Gardens and Their Contribution to Sustainable Development Goal 15 - Life on Land Volume 15 • Number 2

Journal of Botanic Gardens Conservation International Volume 15 • Number 2 • July 2018 Botanic gardens and their contribution to Sustainable Development Goal 15 - Life on Land Volume 15 • Number 2 IN THIS ISSUE... EDITORS EDITORIAL: BOTANIC GARDENS AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOAL 15 .... 02 FEATURES NEWS FROM BGCI .... 04 Suzanne Sharrock Paul Smith Director of Global Secretary General Programmes PLANT HUNTING TALES: SEED COLLECTING IN THE WESTERN CAPE OF SOUTH AFRICA .... 06 Cover Photo: Franklinia alatamaha is extinct in the wild but successfully grown in botanic gardens and arboreta FEATURED GARDEN: SOUTH AFRICA’S NATIONAL BOTANICAL GARDENS .... 09 (Arboretum Wespelaar) Design: Seascape www.seascapedesign.co.uk INTERVIEW: TALKING PLANTS .... 12 BGjournal is published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI). It is published twice a year. Membership is open to all interested individuals, institutions and organisations that support the aims of BGCI. Further details available from: • Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Descanso ARTICLES House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3BW UK. Tel: +44 (0)20 8332 5953, Fax: +44 (0)20 8332 5956, E-mail: [email protected], www.bgci.org SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOAL 15 • BGCI (US) Inc, The Huntington Library, Suzanne Sharrock .... 14 Art Collections and Botanical Gardens, 1151 Oxford Rd, San Marino, CA 91108, USA. Tel: +1 626-405-2100, E-mail: [email protected] SDG15: TARGET 15.1 Internet: www.bgci.org/usa AUROVILLE BOTANICAL GARDENS – CONSERVING TROPICAL DRY • BGCI (China), South China Botanical Garden, EVERGREEN FOREST IN INDIA 1190 Tian Yuan Road, Guangzhou, 510520, China. Paul Blanchflower .... 16 Tel: +86 20 85231992, Email: [email protected], Internet: www.bgci.org/china SDG 15: TARGET 15.3 • BGCI (Southeast Asia), Jean Linsky, BGCI Southeast Asia REVERSING LAND DEGRADATION AND DESERTIFICATION IN Botanic Gardens Network Coordinator, Dr. -

“Clanwilliam Cedar” (Widdringtonia Cedarbergensis JA

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com South African Journal of Botany 76 (2010) 652–654 www.elsevier.com/locate/sajb Chemical composition of the wood and leaf oils from the “Clanwilliam Cedar” (Widdringtonia cedarbergensis J.A. Marsh): A critically endangered species ⁎ G.P.P. Kamatou a, A.M. Viljoen a, , T. Özek b, K.H.C. Başer b a Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Faculty of Science, Tshwane University of Technology, Private Bag X680, Pretoria 0001, South Africa b Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Anadolu University, 26470-Eskişehir, Turkey Received 15 February 2010; received in revised form 31 March 2010; accepted 1 April 2010 Abstract Widdringtonia is the only genus of the 16 genera of Cupressaceae present in South Africa. This genus is represented by three species in South Africa; W. nodiflora, W. schwarzii and W. cedarbergensis (= W. juniperoides) and the latter listed as critically endangered. Cedarwood oil (generally obtained from Juniperus species) is widely used as a fragrance material in several consumer products, however, no data has been published on the volatiles of the Clanwilliam cedar (W. cedarbergensis) native to South Africa. The essential oil composition of the wood and leaf oil isolated by hydro-distillation were analysed by GC–MS. The two oils were distinctly different. Twenty compounds representing 93.8% of the total oil were identified in the leaf oil which was dominated by terpinen-4-ol (36.0%), sabinene (19.2%), γ-terpinene (10.4%), α-terpinene (5.5%) and myrcene (5.5%). Twenty six compounds representing 89.5% of the total were identified in the wood oil with the predominance of thujopsene (47.1%), α-cedrol (10.7%), widdrol (8.5%) and cuparene (4.0%). -

Genetic Structure of Tetraclinis Articulata, an Endangered Conifer of the Western Mediterranean Basin

Silva Fennica vol. 47 no. 5 article id 1073 Category: research article SILVA FENNICA www.silvafennica.fi ISSN-L 0037-5330 | ISSN 2242-4075 (Online) The Finnish Society of Forest Science The Finnish Forest Research Institute Pedro Sánchez-Gómez1, Juan F. Jiménez1, Juan B. Vera1, Francisco J. Sánchez-Saorín2, Juan F. Martínez2 and Joseph Buhagiar3 Genetic structure of Tetraclinis articulata, an endangered conifer of the western Mediterranean basin Sánchez-Gómez P., Jiménez J. F., Vera J. B., Sánchez-Saorín F. J., Martínez J. F., Buhagiar J. (2013). Genetic structure of Tetraclinis articulata, an endangered conifer of the western Mediter- ranean basin. Silva Fennica vol. 45 no. 5 article id 1073. 14 p. Highlights • The employment of ISSR molecular markers has shown moderate genetic diversity and high genetic differentiation in Tetraclinis articulata. • Genetic structure of populations seems to be influenced by the anthropogenic use of this species since historical times, or alternatively, by the complex palaeogeographic history of the Mediterranean basin. • Results could be used to propose management policies for conservation of populations. Abstract Tetraclinis articulata (Vahl) Masters is a tree distributed throughout the western Mediterranean basin. It is included in the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) red list, and protected by law in several of the countries where it grows. In this study we examined the genetic diversity and genetic structure of 14 populations of T. articulata in its whole geographic range using ISSR (inter simple sequence repeat) markers. T. articulata showed moderate genetic diversity at intrapopulation level and high genetic differentiation. The distribution of genetic diversity among populations did not exhibit a linear pattern related to geographic distances, since all analyses (principal coordinate analysis, Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean dendrogram and Bayesian structure analysis) revealed that spanish population grouped with Malta and Tunisia populations. -

Tree Domestication and the History of Plantations - J.W

THE ROLE OF FOOD, AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND FISHERIES IN HUMAN NUTRITION – Vol. II - Tree Domestication and the History of Plantations - J.W. Turnbull TREE DOMESTICATION AND THE HISTORY OF PLANTATIONS J.W. Turnbull CSIRO Forestry and Forest Products, Canberra, Australia Keywords: Industrial plantations, protection forests, urban forestry, clonal forestry, forest management, tree harvesting, tree planting, monoculture, provenance, germplasm, silviculture, botanic gardens, arboreta, fuelwood, molecular biology, genetics, tropical rainforest, pulpwood, shelterbelts, rubber, pharmaceuticals, lumber, fruit trees, palm oil, Eucalyptus, farm forestry, dune stabilization, clear-cutting, religious ceremony Contents 1. Introduction 2. Origins of Planting 2.1. The Mediterranean Lands 2.2. Asia 3. Movement of Germplasm 3.1. Evidence of Early Transfers 3.2. Role of Botanic Gardens and Arboreta 3.3. Australian Tree Species and Their Transfer 3.4. North Asia as a Rich Source 4. Tree Domestication 4.1. Domestication by Indigenous Peoples 4.2. Selection and Breeding of Forest Trees 4.3. Forest Genetics 5. Plantations 6. Forest Plantations 1400–1900 6.1. European Experiences 6.2. Tropical Plantations 7. Plantations 1900–1950 8. Plantations 1950–2000 8.1. Global Overview 9. Protection Forests 10. Amenity Planting and Urban Forestry 11. Plantation Practices 11.1. TheUNESCO Mechanical Revolution – EOLSS 12. Sustainability of Plantations Glossary SAMPLE CHAPTERS Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary Trees have been planted for thousands of years for food, wood, shelter, and religious purposes. The first woody plants to be cultivated were those yielding food, such as the olive. Trees were moved around the world by the Romans, Greeks, Chinese, and by others during military conquests. Voyages of discovery by European navigators to the ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) THE ROLE OF FOOD, AGRICULTURE, FORESTRY AND FISHERIES IN HUMAN NUTRITION – Vol. -

Cheŵa Women's Instructions in South-Central Africa

[Downloaded free from http://www.conservationandsociety.org on Monday, January 16, 2017, IP: 187.227.107.114] Conservation and Society 14(4): 406-415, 2016 Article Animals’ Role in Proper Behaviour: Cheŵa Women’s Instructions in South-Central Africa Leslie F. Zubieta Current affiliation: Centre for Rock Art Research + Management, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, Australia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The most common role of animals in the Cheŵa culture of south-central Africa is twofold: they are regarded as an important source of food, and they also provide raw materials for the creation of traditional medicines. Animals, however, also have a nuanced symbolic role that impacts the way people behave with each other by embodying cultural protocols of proper — and not so proper — behaviour. They appear repeatedly in storytelling and proverbs to reference qualities that people need to avoid or pursue and learn from the moral of the story in which animals interplay with each other, just as humans do. For example, someone who wants to prevent the consequences of greed is often advised to heed hyena stories and proverbs. My contribution elaborates on Brian Morris’s instrumental work in south-central Africa, which has permitted us to elucidate the symbolism of certain animals and the perception of landscape for Indigenous populations in this region. I discuss some of the ways in which animals have been employed to teach and learn proper behaviour in a particular sacred ceremony of the Cheŵa people which takes place in celebration of womanhood: Chinamwali. Keywords: Animal symbolism, initiation, Cheŵa, rock art, behaviour, Indigenous women, south-central Africa, Indigenous knowledge, Chinamwali INTRODUCTION highway.