National Center for Missing & Exploited ®C H I L D R E N 151268 U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Defense Force Times Winter 2020

State Defense Force Times Message from the President Winter 2020 MG Jay Coggan • Increase our external California State Guard communications to educate the public and government at all First, as we start off a new year, let me levels as to our mission congratulate BG Hayhurst and BG • Expand training opportunities Santiago for a great annual conference in across the country and online Biloxi, MS. Unfortunately, prior California State Guard commitments kept Internal communications have been me from attending, but I received great driven mostly by our web, newsletter, and feedback from our members. Your periodic announcements. We will be dedication and work is appreciated! updating our email capabilities to provide As we move into 2020 we have the more relevant and timely information to opportunity to build on our past success our members. To make this effort and make this a transformative year. My successful, I ask that each member please singular mission focus for SAGUS this go to their member profile in the SGAUS year is to improve our communications to web site make sure your contact and make us the most effective organization email information is current. We are that we can be. My key strategies to establishing a team to evaluate and accomplish this goal are: implement new strategies for internal communications. More information on • Improve our communications with this effort will be forthcoming. members 1 Now, regarding external communications, opportunity for SGAUS to SDF help our I firmly believe that this year SGAUS can respective states deal with this issue. take it to the next level in how we make It’s never too early to start planning for ourselves known outside our association the 2020 SAGUS Annual Conference. -

The Strategic Value of Proxies and Auxiliaries in Wars Amongst the People

Conceptualising the regular-irregular engagement: the strategic value of proxies and auxiliaries in wars amongst the people Book or Report Section Accepted Version Rauta, V. (2019) Conceptualising the regular-irregular engagement: the strategic value of proxies and auxiliaries in wars amongst the people. In: Brown, D., Murray, D., Riemann, M., Rossi, N. and Smith, M. (eds.) War Amongst the People. Howgate Publishing Limited, Havant. Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/81725/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Howgate Publishing Limited All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 1 Chapter 5: Conceptualising the Regular-Irregular Engagement: The Strategic Value of Proxies and Auxiliaries in Wars amongst the People Vladimir Rauta Introduction The notion of ‘war amongst the people’ is a central feature of the twenty-first century security environment. Introduced by Rupert Smith in his ground-breaking The Utility of Force,1 ‘war amongst the people’ captured a reality long in the making, whose historical lineage could partly be traced back to the origins of war itself. The appeal of the concept came from combining the simplicity -

Police Department

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. Enhancing Public Safety by Leveraging Resources 0 --.. A Resource Guide for Law Enforcement Agencies J @ 0 @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ @ This project was supported by Award No. 2002-DD-BX-0010 awarded by @ the Bureau of Justice Assistance, Office of Justice Programs. The opinions, @ findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this @ publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the @ views of the Department of Justice. @ @ @ @ @ 0 0 2o 5957 0 0 0 Table of Contents 0 0 0 0 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... i 0 Part h Establishing or Enhancing a Volunteer Program 0 0 Section 1: Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 0 0 Section 2: The Current State of Volunteerism .............................................................. 4 0 Section 3: Building Program Infrastructure ................................................................. 8 0 0 Section 4: Recruitment ....................................................................................................16 0 0 Section 5: Selection and Management ..........................................................................20 0 Section 6: Training ..........................................................................................................24 -

P R O C E E D I N G S of the of the United States

107th_covers 6/21/07 10:41 AM Page 1 110th Congress, 1st Session ......................................................House Document 110-40 P R O C E E D I N G S OF THE 107th NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES [SUMMARY OF MINUTES] Reno, Nevada : : : August 26 - August 31, 2006 107TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS 107th_backstrip 6/21/07 10:58 AM Page 1 107th_covers 6/21/07 10:41 AM Page I 110th Congress, 1st Session ......................................................House Document 110-40 PROCEEDINGS of the 107th ANNUAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Reno, Nevada August 26-31, 2006 Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed. U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2007 36-122 107th 5/25/07 1:05 PM Page II U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the Amer- ican Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House doc- uments of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] II 107th 6/22/07 3:11 PM Page III LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, RENO, NEVADA, April, 2007 Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U.S. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or microfiche but lack the clarity on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, 35mm slides of 6”x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography. O rder N um ber 87X7695 The Japanese merchant marine in World War II Parillo, Mark Philip, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1987 Copyright ©1987 by Parillo, Mark Philip. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

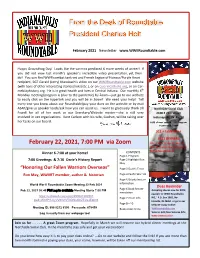

February 22, 2021, 7:00 PM Via Zoom

February 2021 Newsletter www.WWIIRoundtable.com Happy Groundhog Day! Looks like the varmint predicted 6 more weeks of winter! If yo u did not v iew last month’s speaker’s incredible video presentation, yet, then do! You can find WWII combat tank vet and French Legion of Honour/Purple Heart recipient, SGT Gerald (Jerry) Mansbach’s video on our WWiiRoundtable.com website (with tons of other interesting stories/links/etc.), or on GuerinCatholic.org, or on Car- melclayhistory.org. He is in great health and lives in Central Indiana. Our monthly 4th Monday meeting/program is (due to the pandemic) by Zoom—just go to our website to easily click on the hyperlink and you will be in Zoom! We need your help! Tell every-one you know about our Roundtable/pay your dues on the website or by mail ASAP/give us speaker leads/ask how you can assist us. I want to graciously thank Jill Northside Social Club Fewell for all of her work as our Secretary/Website master—she is still very 2100 E 71st Street involved in vet organizations. Kent Carlson with his wife, Gudrun, will be taking over Indianapolis, IN 46220 her tasks on our board. 6:00 dinner served 7:00 Program in person & Zoom $11 + table tip++ 2021 DINNERS February 22, 2021, 7:00 PM via Zoom Feb 22, Mar 22, Apr 26, May 24, June 18, July 26, Aug 25, Sept 27, Dinner 6-7:00 at your home! CONTENTS Oct 18, Nov 22, Dec 27 Page 1 Program 7:00 Greetings & 7:10 Ozzie’s History Report Page 2 Highlight Ron May “Honoring Our Fallen Warriors Overseas” Page 3 Ozzie’s Trivia Ron May, WWIIRT member, author & historian Page 4 Pacific War ’42 Page 5 Shively lecture World War II Roundtable Zoom Meeting 22 Feb 2021 information Dues Reminder Page 6 Book Recom- Feb 22, 2021 06:45 PM Log-In available Meeting Starts 7:00 PM Accepting checks now for 2021; mendation payable to ‘WWII Roundtable, https://us02web.zoom.us/j/89002128390? Page 7 Zoom info INC,’ P.O. -

Irregular Auxiliaries After 1945

Irregular auxiliaries after 1945 Sibylle Scheipers Author contact details: Dr Sibylle Scheipers Senior Lecturer in International Relations University of St Andrews Arts Building The Scores St Andrews KY16 9AX United Kingdom [email protected] Abstract: Collaboration with native auxiliaries in wars in the peripheries of the international system is an age-old practice, the relevance of which is likely to increase in the twenty-first century. Yet, the parameters of such collaboration are understudied. This article aims to contribute to the nascent yet fragmentary scholarship on the use of native auxiliaries. It identifies three intellectual templates of the collaboration between western regular forces and native auxiliaries: the eighteenth century model of auxiliary ‘partisans’ as tactical complements to regular armed forces; the nineteenth century transformation of the ‘partisan’ into the irregular guerrilla fighter and the concomitant rise of the ‘martial races’ discourse; and, finally, the post-1945 model of the loyalist auxiliary as a symbol of the political legitimacy of the counter-insurgent side in wars of decolonization and post-colonial insurgencies. The article focuses on the rise of loyalism after 1945 in particular, a phenomenon that it seeks to understand within the broader context of irregular warfare and the moral reappraisal of irregular fighters after the Second World War. Keywords: colonial war, wars of decolonization, auxiliaries, Malaya, Kenya, Vietnam, Algeria Native auxiliaries in counter-insurgency campaigns and -

Filling the Ranks: Why Lawful Permanent Residents Should Qualify for Law Enforcement Positions

FILLING THE RANKS: WHY LAWFUL PERMANENT RESIDENTS SHOULD QUALIFY FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT POSITIONS www.leitf.org The Law Enforcement Immigration Task Force (LEITF) consists of law enforcement officers from across the United States concerned with the need for immigration policy changes to fix our broken immigration system. The Task Force is concerned with promoting safe communities and respect for the rule of law. ______________________________________________ LAURENCE BENENSON Assistant Director for Immigration Policy and Advocacy National Immigration Forum June 2017 I. INTRODUCTION CONSIDERING In recent years, police departments and sheriff’s offices across the LPRS FOR LAW United States have faced significant challenges in recruiting, retaining, ENFORCEMENT and hiring officers. As they deal with these recruiting shortfalls, law POSITIONS WOULD enforcement agencies also struggle to maintain diverse workforces that EXPAND THE POOL reflect the changing demographics of their local communities. For many departments, a promising pool of recruits is available but OF QUALIFIED untapped: lawful permanent residents (LPRs). Most jurisdictions maintain APPLICANTS a requirement that law enforcement officers be U.S. citizens, but lifting WHILE SATISFYING the citizenship requirement can allow departments to access a diverse, IMPORTANT talented, hardworking, legally present, and patriotic pool of LPR recruits. FORCE NEEDS. Law enforcement leaders can begin to address recruitment challenges and diversity by encouraging their elected officials and other policymakers to change state and local restrictions on the hiring of LPRs. This paper discusses recruitment challenges facing the nation’s police departments and the potential for LPRs to help meet growing workforce gaps. In addition to helping stem the shortage of qualified recruits and helping increase diversity in the workforce, LPRs enhance community policing efforts thanks to their unique backgrounds and skill sets, and because they may reflect the communities they protect. -

Chapter 1: the Legal Framework a Comparative Atlas of Defence in Latin America / 2008 Edition 28

Chapter 1: The Legal Framework A Comparative Atlas of Defence in Latin America / 2008 Edition 28 RESDAL What do the Constitutions define? Country Leading Political Procedures Military Instrument Other Dispositions Argentina Powers of the President: No reference. The Federal Government intervenes in the terri- (1853, Last Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces (Sec. tory of the provinces to repel foreign invasions Reform 1994) 99, sub. 12). (Sec. 6). Declare war with the approval of the Congress Citizen participation: every argentine citizen is (Sec. 99, sub. 15) and the state of siege in case of obliged to bear arms in defence of the Nation external attacks, for a limited period of time, with and the Constitution (Sec. 21). the approval of the Senate (Sec. 99, sub. 16). The international treaties and concordats cele- Appoint senior officers with the approval of the brated with the Holy See have a higher hierar- Senate (Sec. 99, sub. 13). chy than laws (Sec. 75, sub. 22 y 24). Arrange, organise and distribute the Armed Forces (Sec. 99, sub. 14). Powers of the Congress: Approve the declaration of war (Sec. 75, sub. 25) and the declaration of state of siege in case of external attacks (Sec. 61). Authorise the president to make peace (Sec. 75, sub. 25). Authorise the entry of foreign troops to the natio- nal territory and allow the deployment of national troops outside the country (Sec. 75, sub. 28). Establish the Armed Forces (Sec. 75, sub. 27). The Chamber of Deputies has the law initiative on raising revenue and recruitment of troops (Sec. -

Income Tax – Subtraction Modification – Police Auxiliaries and Reserve Volunteers

LAWRENCE J. HOGAN, JR., Governor Ch. 155 Chapter 155 (House Bill 822) AN ACT concerning Income Tax – Subtraction Modification – Police Auxiliaries and Reserve Volunteers FOR the purpose of altering eligibility for and the amount of a subtraction modification under the State income tax for certain qualifying police auxiliaries and reserve volunteers; and generally relating to a subtraction modification under the State income tax for police auxiliaries and reserve volunteers. BY repealing and reenacting, without amendments, Article – Tax – General Section 10–208(a) Annotated Code of Maryland (2016 Replacement Volume) BY repealing and reenacting, with amendments, Article – Tax – General Section 10–208(l) Annotated Code of Maryland (2016 Replacement Volume) SECTION 1. BE IT ENACTED BY THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF MARYLAND, That the Laws of Maryland read as follows: Article – Tax – General 10–208. (a) In addition to the modification under § 10–207 of this subtitle, the amounts under this section are subtracted from the federal adjusted gross income of a resident to determine Maryland adjusted gross income. (l) (1) The subtraction under subsection (a) of this section includes an amount equal to [$3,500] THE AMOUNT SPECIFIED IN PARAGRAPH (3) OF THIS SUBSECTION if an individual is a qualifying police auxiliary or reserve volunteer for the taxable year, as determined under paragraph (2) of this subsection. (2) An individual is a qualifying police auxiliary or reserve volunteer for the taxable year eligible for the subtraction modification under this subsection if the individual: (i) is an active member of a bona fide Maryland police agency; – 1 – Ch. 155 2017 LAWS OF MARYLAND (ii) serves the organization in a volunteer capacity without compensation, except nominal expenses or meals; (iii) 1. -

Dynamics of Aging in the Illinois Law Enforcement Officer Corps

N CD ~ M LO Dynamics of Aging in the Illinois Law Enforcement Officer Corps ILLINOIS CRIMINAL JUSTICE INFORMATION AUTHORITY [ ------------------~I 153462 U.S. Department of JU5ltice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating It. Points of view or opinions stated In this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represeni the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted by I11mois Criminal Justice Infonnation Authority to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. Dynamics of Aging in the llIinois Law Enforcement Officer Corps By Michele Livojevic, Research analyst Sandra Bass, Research assistant Lloyd Babb, Research technician Jackie Front, Technical assistant Jeffrey Travis, 'I'echnical assistant DJinois Criminal Justice Information Authority Peter B. Bensinger, Chairman J. David Coldren, Executive Director Barbara McDonald, Deputy Executive Director February 1992 Acknowledgments The Authority wishes to thank the Illinois Local Governmental Law Enforcement Officers Training Board, the Illinois State Police, and the departments that served as case studies for this research: the Chicago Police Department, the Joliet Police Department, the Bethalto Police Department, and the Madison Country Sheriffs Department. These agencies provided invaluable information that made this study possible. Dynamics of Aging in the Dlinois Law Enforcement Officer Corps Advisory Board The following agencies and their representatives were instrumental to these research efforts. Advisory board members contributed their time, knowledge, and expertise throughout this study. Dr. Tom Jurkanin Honorable Robert E. -

1 Auxiliary Police Units in the Occupied Soviet Union, 1941-43: A

Auxiliary Police Units in the Occupied Soviet Union, 1941-43: A Case Study of the Holocaust in Gomel, Belarus “…the corpses lay with their faces on the dirt. Hands on their heads. One woman lay in a way that showed she had been kneeling, and she fell over her baby. There were four identifiable corpses that revealed a bloody wound on their heads. It was established that they were not old bullet wounds, but it was clear that they and the baby had been murdered; with what extraneous object remains unclear. It was clear that people had been beaten with heavy objects and had then been (disorderly dumped) in a hole. One boy had clearly been buried alive. The corpses were in underwear, without clothes.” 1 This statement, given by Ivan Abramovich on January 16, 1944, was part of the ‘Soviet Extraordinary State Commission to Investigate Fascist Crimes Committed by the Invaders and their Accomplices on Soviet Territory’ during an investigation of German crimes in Gomel, Belorussia. The Soviet regime conducted similar investigations and hearings throughout areas formerly occupied by the Germans in an effort to understand precisely what horrors had occurred beyond the front lines. As the investigations progressed, they learned that the scope of the crimes was tremendously large. Even more disturbing, however, was the discovery that locals across Lithuania, Belorussia and Ukraine were deeply implicated, principally through service in auxiliary police units that openly collaborated with the German forces and participated in atrocities at almost every level. Without the auxiliaries, the Nazi’s murderous intentions toward the Jewish population on the Eastern Front would not have been nearly as deadly; the role of the auxiliary police was pivotal in the Holocaust on the Eastern Front, as they provided support, manpower and critical knowledge of the local region and language to the German forces.