The Dynamics of Nothofagus Cunninghamii Rainforest Associations in Tasmania - an Ecophysiological Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wednesday Walk — Monga Forest Drive — 28 February 2018

Wednesday Walk — Monga Forest Drive — 28 February 2018 Monga National Park, Dasyurus and Waratah Roads and Penance Grove Circuit and Boardwalk Wednesday Walkers have been visiting Monga National Park for over 15 years since the establishment of the Park in 2001, as a result of the regional forests agreement. It still contains patches of old growth forest dominated by brown barrel, E. fastigata, messmate, E. obliqua, and manna gum, E. viminalis, as well as the ancient plumwood, Eucryphia moorei (Cunoniaceae, coachwoods), that is confined to wet gullies. Other parts of the park are regenerating from past logging that fed a timber mill at Monga. Access to the eastern part of the park on the escarpment is via the Corn Trail that is one of our favourite walks, because of its floriferous heathland understory. Further west a network of old logging trails dissect the park around the catchment of the Mongarlowe River. Our regular haunts here are the Dasyurus Road and picnic ground that leads to the Corn Trail Link across the river, the Waratah Road and Picnic Area, where a riverside track has been constructed to view the waratahs, and the Penance Grove loop track that provides a different access to the boardwalk through groves of massive tree ferns and a plumwood gully. Our first stop was the Dasyurus picnic ground for morning tea and a walk along the roadside. With each visit, the trees are getting taller and some must be getting to the 50m mark. I should borrow a clinometer to measure their true height. Three species dominate: messmate, E. -

Nothofagus, Key Genus of Plant Geography, in Time

Nothofagus, key genus of plant geography, in time and space, living and fossil, ecology and phylogeny C.G.G.J. van Steenis Rijksherbarium, Leyden, Holland Contents Summary 65 1. Introduction 66 New 2. Caledonian species 67 of and Caledonia 3. Altitudinal range Nothofagus in New Guinea New 67 Notes of 4. on distribution Nothofagus species in New Guinea 70 5. Dominance of Nothofagus 71 6. Symbionts of Nothofagus 72 7. Regeneration and germination of Nothofagus in New Guinea 73 8. Dispersal in Nothofagus and its implications for the genesis of its distribution 74 9. The South Pacific and subantarctic climate, present and past 76 10. The fossil record 78 of in time and 11. Phylogeny Nothofagus space 83 12. Bi-hemispheric ranges homologous with that of Fagoideae 89 13. Concluding theses 93 Acknowledgements 95 Bibliography 95 Postscript 97 Summary Data are given on the taxonomy and ecology of the genus. Some New Caledonian in descend the lowland. Details the distri- species grow or to are provided on bution within New Guinea. For dominance of Nothofagus, and Fagaceae in general, it is suggested that this. Some in New possibly symbionts may contribute to notes are made onregeneration and germination Guinea. A is devoted a discussion of which to be with the special chapter to dispersal appears extremely slow, implication that Nothofagus indubitably needs land for its spread, and has needed such for attaining its colossal range, encircling onwards of New Guinea the South Pacific (fossil pollen in Antarctica) to as far as southern South America. Map 1. An is other chapter devoted to response ofNothofagus to the present climate. -

Vegetation Benchmarks Rainforest and Related Scrub

Vegetation Benchmarks Rainforest and related scrub Eucryphia lucida Vegetation Condition Benchmarks version 1 Rainforest and Related Scrub RPW Athrotaxis cupressoides open woodland: Sphagnum peatland facies Community Description: Athrotaxis cupressoides (5–8 m) forms small woodland patches or appears as copses and scattered small trees. On the Central Plateau (and other dolerite areas such as Mount Field), broad poorly– drained valleys and small glacial depressions may contain scattered A. cupressoides trees and copses over Sphagnum cristatum bogs. In the treeless gaps, Sphagnum cristatum is usually overgrown by a combination of any of Richea scoparia, R. gunnii, Baloskion australe, Epacris gunnii and Gleichenia alpina. This is one of three benchmarks available for assessing the condition of RPW. This is the appropriate benchmark to use in assessing the condition of the Sphagnum facies of the listed Athrotaxis cupressoides open woodland community (Schedule 3A, Nature Conservation Act 2002). Benchmarks: Length Component Cover % Height (m) DBH (cm) #/ha (m)/0.1 ha Canopy 10% - - - Large Trees - 6 20 5 Organic Litter 10% - Logs ≥ 10 - 2 Large Logs ≥ 10 Recruitment Continuous Understorey Life Forms LF code # Spp Cover % Immature tree IT 1 1 Medium shrub/small shrub S 3 30 Medium sedge/rush/sagg/lily MSR 2 10 Ground fern GF 1 1 Mosses and Lichens ML 1 70 Total 5 8 Last reviewed – 2 November 2016 Tasmanian Vegetation Monitoring and Mapping Program Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment http://www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au/tasveg RPW Athrotaxis cupressoides open woodland: Sphagnum facies Species lists: Canopy Tree Species Common Name Notes Athrotaxis cupressoides pencil pine Present as a sparse canopy Typical Understorey Species * Common Name LF Code Epacris gunnii coral heath S Richea scoparia scoparia S Richea gunnii bog candleheath S Astelia alpina pineapple grass MSR Baloskion australe southern cordrush MSR Gleichenia alpina dwarf coralfern GF Sphagnum cristatum sphagnum ML *This list is provided as a guide only. -

An Early Paleogene Pollen and Spore Assemblage from the Sabrina Coast, East Antarctica

Palynology ISSN: 0191-6122 (Print) 1558-9188 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tpal20 New species from the Sabrina Flora: an early Paleogene pollen and spore assemblage from the Sabrina Coast, East Antarctica Catherine Smith, Sophie Warny, Amelia E. Shevenell, Sean P.S. Gulick & Amy Leventer To cite this article: Catherine Smith, Sophie Warny, Amelia E. Shevenell, Sean P.S. Gulick & Amy Leventer (2019) New species from the Sabrina Flora: an early Paleogene pollen and spore assemblage from the Sabrina Coast, East Antarctica, Palynology, 43:4, 650-659, DOI: 10.1080/01916122.2018.1471422 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01916122.2018.1471422 Published online: 12 Dec 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 116 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tpal20 PALYNOLOGY 2019, VOL. 43, NO. 4, 650–659 https://doi.org/10.1080/01916122.2018.1471422 New species from the Sabrina Flora: an early Paleogene pollen and spore assemblage from the Sabrina Coast, East Antarctica Catherine Smitha, Sophie Warnyb, Amelia E. Shevenella, Sean P.S. Gulickc and Amy Leventerd aCollege of Marine Science, University of South Florida, St. Petersburg, FL, USA; bDepartment of Geology and Geophysics and Museum of Natural Science, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA; cInstitute of Geophysics and Department of Geological Sciences, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA; dDepartment of Geology, Colgate University, Hamilton, NY, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Palynological analyses of 13 samples from two sediment cores retrieved from the Sabrina Coast, East Paleocene; Eocene; Aurora Antarctica provide rare information regarding the paleovegetation within the Aurora Basin, which Basin; Sabrina Coast; East today is covered by the East Antarctic Ice Sheet. -

Pollination Ecology and Evolution of Epacrids

Pollination Ecology and Evolution of Epacrids by Karen A. Johnson BSc (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania February 2012 ii Declaration of originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Karen A. Johnson Statement of authority of access This thesis may be made available for copying. Copying of any part of this thesis is prohibited for two years from the date this statement was signed; after that time limited copying is permitted in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Karen A. Johnson iii iv Abstract Relationships between plants and their pollinators are thought to have played a major role in the morphological diversification of angiosperms. The epacrids (subfamily Styphelioideae) comprise more than 550 species of woody plants ranging from small prostrate shrubs to temperate rainforest emergents. Their range extends from SE Asia through Oceania to Tierra del Fuego with their highest diversity in Australia. The overall aim of the thesis is to determine the relationships between epacrid floral features and potential pollinators, and assess the evolutionary status of any pollination syndromes. The main hypotheses were that flower characteristics relate to pollinators in predictable ways; and that there is convergent evolution in the development of pollination syndromes. -

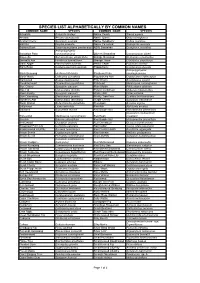

Species List Alphabetically by Common Names

SPECIES LIST ALPHABETICALLY BY COMMON NAMES COMMON NAME SPECIES COMMON NAME SPECIES Actephila Actephila lindleyi Native Peach Trema aspera Ancana Ancana stenopetala Native Quince Guioa semiglauca Austral Cherry Syzygium australe Native Raspberry Rubus rosifolius Ball Nut Floydia praealta Native Tamarind Diploglottis australis Banana Bush Tabernaemontana pandacaqui NSW Sassafras Doryphora sassafras Archontophoenix Bangalow Palm cunninghamiana Oliver's Sassafras Cinnamomum oliveri Bauerella Sarcomelicope simplicifolia Orange Boxwood Denhamia celastroides Bennetts Ash Flindersia bennettiana Orange Thorn Citriobatus pauciflorus Black Apple Planchonella australis Pencil Cedar Polyscias murrayi Black Bean Castanospermum australe Pepperberry Cryptocarya obovata Archontophoenix Black Booyong Heritiera trifoliolata Picabeen Palm cunninghamiana Black Wattle Callicoma serratifolia Pigeonberry Ash Cryptocarya erythroxylon Blackwood Acacia melanoxylon Pink Cherry Austrobuxus swainii Bleeding Heart Omalanthus populifolius Pinkheart Medicosma cunninghamii Blue Cherry Syzygium oleosum Plum Myrtle Pilidiostigma glabrum Blue Fig Elaeocarpus grandis Poison Corkwood Duboisia myoporoides Blue Lillypilly Syzygium oleosum Prickly Ash Orites excelsa Blue Quandong Elaeocarpus grandis Prickly Tree Fern Cyathea leichhardtiana Blueberry Ash Elaeocarpus reticulatus Purple Cherry Syzygium crebrinerve Blush Walnut Beilschmiedia obtusifolia Red Apple Acmena ingens Bollywood Litsea reticulata Red Ash Alphitonia excelsa Bolwarra Eupomatia laurina Red Bauple Nut Hicksbeachia -

Epacris Study Group

ASSOCIATION OF SOCIETIES FOR GROWING AUSTRALIAN PLANTS Inc. EPACRIS STUDY GROUP Group Leader: Gwen Elliot, P.O. Box 655 Heathmont Vic. 3135 NEWSLETTER No. XS (ISSN 103 8-6017) Qctaber zaQ4 Greetings as once again we begin to enjoy the longer days of spring-summer and the encouragement this provides for many of our flowering plants. Despite the generally dry conditions many Epacris species are putting on outstanding floral displays. How are you going with your recording of the flowering times of Epacris impressa in your garden, as well as in nearby bushland or in other areas as you travel within Australia? It really is quite an exciting project because together we, as Study Group members, can make a real contribution to the overall understanding of this species, adding to the knowledge and research of botanists who look in detail at the features of the plant under the microscope and in its natural habitat. It iis a species which occurs both atsea-level and at higher altitudes. How are the flowering times affected when highland plants are cultivated at lower altitudes? Are flowering times different when plants fiom New South Wales for example are gvown much further south in soulhern Victoria or Tasmania ? Epacris impressu seems like an excellent species for us to research in this way. If our project is successful we may perhaps be able to continue with looking at the flowering times of other Epacris which are relatively common in cultivation. In case you have misplaced the recording sheet from our October 2003 Newsletter, another is included in this issue. -

Plant Life of Western Australia

INTRODUCTION The characteristic features of the vegetation of Australia I. General Physiography At present the animals and plants of Australia are isolated from the rest of the world, except by way of the Torres Straits to New Guinea and southeast Asia. Even here adverse climatic conditions restrict or make it impossible for migration. Over a long period this isolation has meant that even what was common to the floras of the southern Asiatic Archipelago and Australia has become restricted to small areas. This resulted in an ever increasing divergence. As a consequence, Australia is a true island continent, with its own peculiar flora and fauna. As in southern Africa, Australia is largely an extensive plateau, although at a lower elevation. As in Africa too, the plateau increases gradually in height towards the east, culminating in a high ridge from which the land then drops steeply to a narrow coastal plain crossed by short rivers. On the west coast the plateau is only 00-00 m in height but there is usually an abrupt descent to the narrow coastal region. The plateau drops towards the center, and the major rivers flow into this depression. Fed from the high eastern margin of the plateau, these rivers run through low rainfall areas to the sea. While the tropical northern region is characterized by a wet summer and dry win- ter, the actual amount of rain is determined by additional factors. On the mountainous east coast the rainfall is high, while it diminishes with surprising rapidity towards the interior. Thus in New South Wales, the yearly rainfall at the edge of the plateau and the adjacent coast often reaches over 100 cm. -

Reconstructing the Basal Angiosperm Phylogeny: Evaluating Information Content of Mitochondrial Genes

55 (4) • November 2006: 837–856 Qiu & al. • Basal angiosperm phylogeny Reconstructing the basal angiosperm phylogeny: evaluating information content of mitochondrial genes Yin-Long Qiu1, Libo Li, Tory A. Hendry, Ruiqi Li, David W. Taylor, Michael J. Issa, Alexander J. Ronen, Mona L. Vekaria & Adam M. White 1Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, The University Herbarium, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1048, U.S.A. [email protected] (author for correspondence). Three mitochondrial (atp1, matR, nad5), four chloroplast (atpB, matK, rbcL, rpoC2), and one nuclear (18S) genes from 162 seed plants, representing all major lineages of gymnosperms and angiosperms, were analyzed together in a supermatrix or in various partitions using likelihood and parsimony methods. The results show that Amborella + Nymphaeales together constitute the first diverging lineage of angiosperms, and that the topology of Amborella alone being sister to all other angiosperms likely represents a local long branch attrac- tion artifact. The monophyly of magnoliids, as well as sister relationships between Magnoliales and Laurales, and between Canellales and Piperales, are all strongly supported. The sister relationship to eudicots of Ceratophyllum is not strongly supported by this study; instead a placement of the genus with Chloranthaceae receives moderate support in the mitochondrial gene analyses. Relationships among magnoliids, monocots, and eudicots remain unresolved. Direct comparisons of analytic results from several data partitions with or without RNA editing sites show that in multigene analyses, RNA editing has no effect on well supported rela- tionships, but minor effect on weakly supported ones. Finally, comparisons of results from separate analyses of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes demonstrate that mitochondrial genes, with overall slower rates of sub- stitution than chloroplast genes, are informative phylogenetic markers, and are particularly suitable for resolv- ing deep relationships. -

The Ecology and Biogeography of Athrotaxis D. Don

THE ECOLOGY AND BIOGEOGRAPHY OF ATHROTAXIS D. DON. ,smo,e5 by Philip J. Cullen B.Sc. (Forestry) submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA HOBART February 1987 DECLARATION This thesis contains no material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university and contains no copy or paraphrases of material previously published or writtern by another person, except where due reference is made in the text. P. J. Cullen. CONTENTS PAGE ACKNOWLEGEMENTS ABSTRACT II LIST OF FIGURES IV LIST OF TABLES VI LIST OF PLATES VIII CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION , 1 CHAPTER 2: DISTRIBUTION AND SYNECOLOGY 2.1 Introduction 8 2.2 Methods 14 2.3 Results and Discussion 2.3.1 Stand Classification 19 2.3.2 Stand Ordination 32 CHAPTER 3: THE REGENERATION MODES OF ATHROTAXIS CUPRESSOIDES AND ATHROTAXIS SELAGINOIDES 3.1 Introduction 38 3.2 Methods 3.2.1 Stand demography 40 3.2.2 Spatial distribution of seedlings 43 3.2.3 Seed dispersal 44 3.2.4 Vegetative reproduction 45 3.3 Results and Discussion 3.3.1 Size/age correlations 48 3.3.2 Seed production and dispersal 52 3.3.3 Vegetative regeneration 55 3.3.4 Stand demography and seedling distribution of Athrotaxis cupressoides 60 3.3.5 Stand demography and seedling distribution of Athrotaxis seiaginoides 82 3.3.6 The presence of Athrotaxis laxifolia . 88 3.4 Conclusion 89 CHAPTER THE RELATIVE FROST RESISTANCE OF ATHROTAXIS CUPRESSOIDES AND ATHROTAXIS SELAGINOIDES SEEDLINGS 4.1 Introduction 92 4.2 Methods 93 4,3 Results 96 4.4 Discussion 99 CHAPTER 5: THE EFFECT OF GRAZING ON THE SEEDLING REGENERATION OF ATHROTAXIS CUPRESSOIDES 5.1 Introduction 107 5.2 Methods 107 5.3 Results 109 5.4 Discussion 111 CHAPTER 6: DISCUSSION 116 REFERENCES 135 APPENDIX A: REGENERATION PATTERNS IN POPULATIONS OF ATHROTAXIS SELAGINOIDES D. -

Tasmania - from the Wet West to the Dry East

This collection is maintained with the assistance of the Tasmania - from the wet west to the dry east. Regional Branch of the Australian Plant Society. Influences on the development of the Tasmanian plant mix Montane moorland and cool oceanic heathland When Gondwana existed as a super Geology of Tasmania Vegetation Map of Tasmania The Tasmanian highland vegetation developed in isolation from the Australian Alps. Even during ice continent, Australia and Tasmania, Africa, ages, hundreds of kilometres of lowland vegetation separated the two high altitude environments. South America, New Zealand and Antarctica shared many plant families and some Montane plants have to cope with wide temperature fluctuations, with periods of below 0°C and Genera. exposure to winds. Cold may be prolonged if the ground freezes. Plants may be blanketed by snow or BASS STRAIT the mountains by cloud. Snowmelt or clear weather can cause intense rays of light, resulting in high For example, the protea family has members temperature. Wind or sun can dry the plant and soil. in all those land masses except Antarctica. The Southern Africa panel covers the protea family more fully. Plants require moisture and warmth. Small hard leaves offer Tasmania was the last land mass to break protection from the drying away from Antarctica. The opening of the effects of sun and wind. Low gap between these land masses allowed the ocean to circulate growth avoids wind. Branches around Antarctica, cooling the earth’s climate and so locking up grow close together to shelter vast quantities of water as ice. the parts of each plant. -

World Heritage Values and to Identify New Values

FLORISTIC VALUES OF THE TASMANIAN WILDERNESS WORLD HERITAGE AREA J. Balmer, J. Whinam, J. Kelman, J.B. Kirkpatrick & E. Lazarus Nature Conservation Branch Report October 2004 This report was prepared under the direction of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment (World Heritage Area Vegetation Program). Commonwealth Government funds were contributed to the project through the World Heritage Area program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment or those of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. ISSN 1441–0680 Copyright 2003 Crown in right of State of Tasmania Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any means without permission from the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment. Published by Nature Conservation Branch Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment GPO Box 44 Hobart Tasmania, 7001 Front Cover Photograph: Alpine bolster heath (1050 metres) at Mt Anne. Stunted Nothofagus cunninghamii is shrouded in mist with Richea pandanifolia scattered throughout and Astelia alpina in the foreground. Photograph taken by Grant Dixon Back Cover Photograph: Nothofagus gunnii leaf with fossil imprint in deposits dating from 35-40 million years ago: Photograph taken by Greg Jordan Cite as: Balmer J., Whinam J., Kelman J., Kirkpatrick J.B. & Lazarus E. (2004) A review of the floristic values of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Nature Conservation Report 2004/3. Department of Primary Industries Water and Environment, Tasmania, Australia T ABLE OF C ONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................................1 1.