Jessie William Adams House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago from 1871-1893 Is the Focus of This Lecture

Chicago from 1871-1893 is the focus of this lecture. [19 Nov 2013 - abridged in part from the course Perspectives on the Evolution of Structures which introduces the principles of Structural Art and the lecture Root, Khan, and the Rise of the Skyscraper (Chicago). A lecture based in part on David Billington’s Princeton course and by scholarship from B. Schafer on Chicago. Carl Condit’s work on Chicago history and Daniel Hoffman’s books on Root provide the most important sources for this work. Also Leslie’s recent work on Chicago has become an important source. Significant new notes and themes have been added to this version after new reading in 2013] [24 Feb 2014, added Sullivan in for the Perspectives course version of this lecture, added more signposts etc. w.r.t to what the students need and some active exercises.] image: http://www.richard- seaman.com/USA/Cities/Chicago/Landmarks/index.ht ml Chicago today demonstrates the allure and power of the skyscraper, and here on these very same blocks is where the skyscraper was born. image: 7-33 chicago fire ruins_150dpi.jpg, replaced with same picture from wikimedia commons 2013 Here we see the result of the great Chicago fire of 1871, shown from corner of Dearborn and Monroe Streets. This is the most obvious social condition to give birth to the skyscraper, but other forces were at work too. Social conditions in Chicago were unique in 1871. Of course the fire destroyed the CBD. The CBD is unique being hemmed in by the Lakes and the railroads. -

Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2015–2016 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program The Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Program includes 30 historic sites across the United States. FLWR on your membership card indicates that you enjoy the National Reciprocal sites benefit. Benefits vary from site to site. Please check websites listed in this brochure for detailed information on each site. ALABAMA ARIZONA CALIFORNIA FLORIDA 1 Rosenbaum House 2 Taliesin West 3 Hollyhock House 4 Florida Southern College 601 RIVERVIEW DRIVE 12621 N. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BLVD BARNSDALL PARK 750 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT WAY FLORENCE, AL 35630 SCOTTSDALE, AZ 85261-4430 4800 HOLLYWOOD BLVD LAKELAND, FL 33801 256.718.5050 480.860.2700 LOS ANGELES, CA 90027 863.680.4597 ROSENBAUMHOUSE.COM FRANKLLOYDWRIGHT.ORG 323.644.6269 FLSOUTHERN.EDU/FLW WRIGHTINALABAMA.COM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION BARNSDALL.ORG FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: 9AM–4PM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: TOUR HOURS: BOOKSHOP HOURS: 8:30AM–6PM TOUR HOURS: THURS–SUN, 11AM–4PM OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT TOUR TICKETS AVAILABLE AT THE THANKSGIVING, CHRISTMAS AND NEW Experience firsthand Frank Lloyd MAJOR HOLIDAYS. HOLLYHOCK HOUSE VISITOR’S CENTER YEAR’S DAY. 10AM–4PM Wright’s brilliant ability to integrate TUES–SAT, 10AM–4PM IN BARNSDALL PARK. VISITOR CENTER & GIFT SHOP HOURS: SUN, 1PM–4PM indoor and outdoor spaces at Taliesin Hollyhock House is Wright’s first 9:30AM–4:30PM West—Wright’s winter home, school The Rosenbaum House is the only Los Angeles project. Built between and studio from 1937-1959, located Discover the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright-designed 1919 and 1923, it represents his on 600 acres of dramatic desert. -

Starchitect:” Wright Finds His Voice After Being Fired

Athens Journal of Architecture - Volume 5, Issue 3– Pages 301-318 After the “Starchitect:” Wright Finds his Voice after Being Fired By Michael O'Brien * The term ―Starchitect‖ seems to have originated in the 1940’s to describe a ―film star who has designed a house‖ but of late has been understood as an architect who has risen to celebrity status in the general culture. Louis Sullivan, like Daniel Burnham, might have been considered a ―starchitect.‖ Starchitects are frequently associated with a unique style or approach to architecture and all who work for them, adopt this style as their own as a matter of employment. Frank Lloyd Wright was one of these architects, working under and in the idiom of Louis Sullivan for six years, learning to draw and develop motifs in the style of Louis Sullivan. Frank Lloyd Wright’s firing by Louis Sullivan in 1893 and his rapidly growing family set him on an urgent course to seek his own voice. The bootleg houses, designed outside the contract terms Wright had with Adler and Sullivan caused the separation, likely fueled by both Sullivan and Wright’s ego, which left Wright alone, separated from his ―Lieber Meister‖1 or ―Beloved Master.‖ These early houses by Wright were adaptations of various styles popular in the times, Neo-Colonial for Blossom, Victorian for Parker and Gale, each, as Wright explained were not ―radical‖ because ―I could not follow up on them.‖2 Wright, like many young architects, had not yet codified his ideas and strategies for activating space and form. How does one undertake the search for one’s language of these architectural essentials? Does one randomly pursue a course of trial and error casting about through images that capture one’s attention? Do we restrict our voice to that which has already been voiced in history? Wright’s agenda would have included the merging of space and enclosure with site and nature structured as he understood it from Sullivan’s Ornament. -

The Rookery Building and Chicago-Kent

Chicago-Kent College of Law Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law 125th Anniversary Materials 125th Anniversary 2-23-2013 The Rookery Building and Chicago-Kent A. Dan Tarlock Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/docs_125 Part of the Legal Commons, Legal Education Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Tarlock, A. Dan, "The Rookery Building and Chicago-Kent" (2013). 125th Anniversary Materials. 12. https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/docs_125/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 125th Anniversary at Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in 125th Anniversary Materials by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 14 Then & Now: Stories of Law and Progress Rookery Building, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress. THE ROOKERY BUILDING AND CHICAGO-KENT A. Dan Tarlock hicago-Kent traces its ori- sustain Chicago as a world city, thus gin to the incorporation of making it an attractive and exciting the Chicago College of Law in place to practice law to the benefit C1888. Chicago-Kent’s founding coin- of all law schools in Chicago in- cided with the opening of the Rook- cluding Chicago-Kent. ery Building designed by the preem- The Rookery is now a classic ex- inent architectural firm of Burnham ample of the first school of Chica- and Root. There is a direct connec- go architecture which helped shape tion between the now iconic Rook- modern Chicago and continues to ery Building, located at Adams and make Chicago a special place, de- LaSalle, and the law school building spite decades of desecration of this further west on Adams. -

Frank Lloyd Wright

'SBOL-MPZE8SJHIU )JTUPSJD"NFSJDBO #VJMEJOHT4VSWFZ '$#PHL)PVTF $PNQJMFECZ.BSD3PDILJOE Frank Lloyd Wright Historic American Buildings Survey Sample: F. C. Bogk House Compiled by Marc Rochkind Frank Lloyd Wright: Historic American Buildings Survey, Sample Compiled by Marc Rochkind ©2012,2015 by Marc Rochkind. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted or reproduced in any form or by any means (including electronic) without permission in writing from the copyright holder. Copyright does not apply to HABS materials downloaded from the Library of Congress website, although it does apply to the arrangement and formatting of those materials in this book. For information about other works by Marc Rochkind, including books and apps based on Library of Congress materials, please go to basepath.com. Introduction The Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) was started in 1933 as one of the New Deal make-work programs, to employ jobless architects, draftspeople, and photographers. Its purpose is to document the nation’s architectural heritage, especially those buildings that are in danger of ruin or deliberate destruction. Today, the HABS is part of the National Park Service and its repository is in the Library of Congress, much of which is available online at loc.gov. Of the tens of thousands HABS buildings, I found 44 Frank Lloyd Wright designs that have been digitized. Each HABS survey includes photographs and/or drawings and/or a report. I’ve included here what the Library of Congress had–sometimes all three, sometimes two of the three, and sometimes just one. There might be a single photo or drawing, or, such as in the case of Florida Southern College (in volume two), over a hundred. -

Christie's to Auction Architectural Elements Of

For Immediate Release May 8, 2009 Contact: Milena Sales 212.636.2680 [email protected] CHRISTIE’S TO AUCTION ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS OF THE DANKMAR ADLER & LOUIS SULLIVAN’S CHICAGO STOCK EXCHANGE BUILDING IN EXCEPTIONAL SALE THIS JUNE 20th Century Decorative Art & Design June 2, 2009 New York – Christie’s New York’s Spring 20th Century Decorative Art & Design sale takes place June 2 and will provide an exciting array of engaging and appealing works from all the major movements of the 20th century, exemplifying the most creative and captivating designs that spanned the century. A separate release is available. A highlight of this sale is the superb group of 7 lots featuring architectural elements from Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan’s Chicago Stock Exchange Building. Jeni Sandberg, Christie's Specialist, 20th Century Decorative Art & Design says, “Christie’s prides itself on bringing works of historical importance and cultural relevance to the international art market. We are therefore delighted to offer these remarkable lots, which were designed by Louis Sullivan, one the great creative geniuses of American Architectural history, in our upcoming 20th Century Decorative Art and Design Sale June 2, 2009.” Louis Sullivan and the Chicago Stock Exchange Building Widely acknowledged as one of the 20th century’s most important and influential American architects, Louis Sullivan is considered by many as “the father of modern architecture.” Espousing the influential notion that “form ever follows function,’ Sullivan redefined the architectural mindset of subsequent generations. Despite this seemingly stark dictum, Sullivan is perhaps best known for his use of lush ornament. Natural forms were abstracted and multiplied into until recognizable only as swirling linear elements. -

Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" If Property Is Not Part of a Multiple Property Listing)

NPS Form 10900 OMB No. 10240018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name State of Illinois Center other names/site number James R. Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 100 West Randolph Street not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60601 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date Illinois Department of Natural Resources - SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

CHARNLEY, JAMES, HOUSE Ot

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CHARNLEY, JAMES, HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: CHARNLEY, JAMES, HOUSE Other Name/Site Number: CHARNLEY-PERSKY HOUSE 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 1365 North Astor Street Not for publication: City/Town: Chicago Vicinity: State: IL County: Cook Code:031 Zip Code:60610-2144 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X_ Building(s): X Public-Local: __ District: __ Public-State: __ Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 __ buildings __ sites __ structures __ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CHARNLEY, JAMES, HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

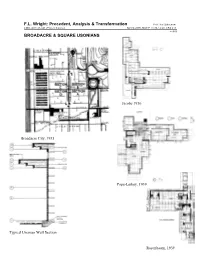

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright 1. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3g04297 5. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.il0039 Some designs and executed buildings by Frank Frederick C. Robie House, 5757 Woodlawn Avenue, Lloyd Wright, architect Chicago, Cook County, IL 2. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3g01871 House ("Bogk House") for Frederick C. Bogk, 2420 North Terrace Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Stone lintel] http://memory.loc.gov/cgi- bin/query/r?pp/hh:@field(DOCID+@lit(PA1690)) Fallingwater, State Route 381 (Stewart Township), Ohiopyle vicinity, Fayette County, PA 3. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/gsc.5a25495 Guggenheim Museum, 88th St. & 5th Ave., New York City. Under construction III. 6. 4. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c11252 http://memory.loc.gov/cgi- bin/query/r?ammem/alad:@field(DOCID+@lit(h19 Frank Lloyd Wright, Baroness Hilla Rebay, and 240)) Solomon R. Guggenheim standing beside a model of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum] / Midway Gardens, interior, Chicago, IL Margaret Carson #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6 #7 PREVIOUS NEXT RECORDS LIST NEW SEARCH HELP Item 10 of 375 How to obtain copies of this item TITLE: Some designs and executed buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright, architect CALL NUMBER: Illus in NA737.W7 A4 1917 (Case Y) [P&P] REPRODUCTION NUMBER: LC-USZC4-4297 (color film copy transparency) LC-USZ62-116098 (b&w film copy neg.) SUMMARY: Silhouette of building with steeples on cover of Japanese journal issue devoted to Frank Lloyd Wright, with Japanese and English text. MEDIUM: 1 print : woodcut(?), color. CREATED/PUBLISHED: [1917] NOTES: Illus. -

Frank Lloyd Wright Itinerary

enjoyillinois.com Frank Lloyd Wright Itinerary Early Works and Triumphs in Chicago A YOUNG ARCHITECT BUILDS HIS REPUTATION IN THE WINDY CITY Spend a day in Chicago exploring some of Frank Lloyd Wright’s most famous designs, from his early collaborations to a solo masterpiece. Charnley-Persky House Museum The Rookery Robie House Like most in his trade, Frank Lloyd Wright Built by Chicago’s preeminent architects, Designed in 1910, the Frederick C. Robie began his career as a draftsman, working Daniel Burnham and John Root, in 1888, House cemented Wright’s reputation in the studio of a more established this early iron skyscraper is notable as a singular architectural talent. Often architect. In Wright’s case, it was Louis enough for its history in Chicago considered the crown jewel of the Prairie Sullivan—a titan of Chicago architecture architecture. But the real reason to style—an aesthetic that Wright both in his own right—who took him on as a visit The Rookery is to see the careful pioneered and perfected—the home protégé. Sullivan grew to trust Wright orchestrations of sunlight streaming reflects the Midwest’s flat plains with its enough to let him contribute to the through the glass lobby, which Wright horizontal lines, low-pitched roofs, and design of residential commissions, remodeled in 1905—instantly updating clever use of natural materials such as including the James Charnley House in Burnham and Root’s drab ironwork for brick and wood. 1892—a collaboration that some consider the 20th Century. How to Visit: The Frank Lloyd Wright the first truly modern American home. -

SECAC Newsletter Katrina Report II 2005

secacNEWSLETTER ADDENDUM Vol. XXXVIII, no. 3 • http://www.furman.edu/secac Thoughts on the Cultural Impact of Katrina: People and Things and a web-site status report BY ROBERT M. CRAIG PART II: STATUS REPORT New Orleans My inquiry into the impact of Katrina on cultural resources in the region was undertaken because I currently serve as President of the Nineteenth Century Studies Association, and as an architectural historian, I see much of the physical New Orleans as a nineteenth century city, filled, street after street (and from high style to vernacular) with structures quintessentially nineteenth century. So much of the city is characterized by historic architecture and neighborhoods of vernacular Victorians with wood-framed, elaborately ornamented front porches; especially noteworthy are those unique “shot-guns” with rear second floor “camelbacks.” New Orleans’s architectural history, it might be said, almost started afresh as the nineteenth century opened, setting the stage for an essentially nineteenth-century place. Two extensive fires, one in 1788, and the other in 1794, devastated the city, destroying hundreds of 18th century buildings, both businesses and residences. New Orleans, and Louisiana, were under Spanish rule at the time, although the city, as it then existed, was a relatively crudely built French port and trading post. Nevertheless, it was ennobled by its open [Jackson] square dominated by St. Louis Cathedral (facade 1789-94, by G. Guillemard), and the Cabildo and Presbytery (both 1794-1813). The Presbytery was undergoing a $2 million renovation this past summer. The further development of the cathedral architecture by J. N. B. de Pouilly in1850, and the building of the Pontalba Apartments (1850s) on the sides of the square brought even this French Quarter focal urban space out of the colonial era and into the urbane nineteenth century.