The Iafor European Conference Series 2014 Ece2014 Ecll2014 Ectc2014 Official Conference Proceedings ISSN: 2188-112X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

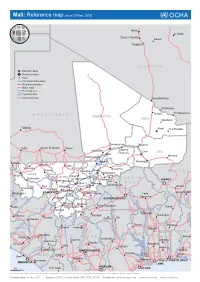

20131217 Mli Reference Map.Pdf

Mali: Reference map (as of 29 Nov. 2013) AdrarP! !In Salah Zaouiet Kounta ! Aoulef ! ! Reggane ALGERIA National capital Regional capital Town International boundary ! Regional boundary Major road Perennial river Perennial lake Intermittent lake Bordj Mokhtar ! !Timiaouine ! Tin Zaouaten Tessalit ! MAURITANIA TOMBOUCTOU KIDAL Abeïbara ! Tidjikdja ! Kidal Ti-n-Essako P! ! Tombouctou Bourem ! Ayoun El Atrous ! Kiffa ! Néma P! ! ! Goundam Gourma- ! Gao GAO !Diré Rharous P! Ménaka Niafounké ! ! ! Youwarou Ansongo ! Sélibaby ! ! ! Nioro ! MOPTI Nara Niger ! Sénégal Yélimané SEGOU Mopti Douentza !Diéma Tenenkou ! P! NIGER SENEGAL P! Bandiagara KAYES ! Kayes ! Koro KOULIKORO Niono Djenné ! ! ! ! BURKINA !Bafoulabé Ké-Macina Bankass NIAMEY KolokaniBanamba ! ! P!Ségou ! FASO \! Bani! Tominian Kita ! Ouahigouya Dosso ! Barouéli! San ! Keniéba ! ! Baoulé Kati P! Nakanbé (White Volta) ! Koulikoro Bla ! \! Birnin Kebbi Kédougou BAMAKO ! KoutialaYorosso Fada Niger ! Dioila ! ! \! Ngourma Sokoto Kangaba ! ! SIKASSO OUAGADOUGOU Bafing Bougouni Gambia ! Sikasso ! P! Bobo-Dioulasso Kandi ! ! Mouhoun (Black Volta) Labé Kolondieba! ! GUINEA Yanfolila Oti Kadiolo ! ! ! Dapango Baoulé Natitingou ! Mamou ! Banfora ! ! Kankan Wa !Faranah Gaoua ! Bagoé Niger ! Tamale Rokel ! OuéméParakou ! ! SIERRA Odienné Korhogo Sokodé ! LEONE CÔTE GHANA BENIN NIGERIA Voinjama ! TOGO Ilorin ! Kailahun! D’IVOIRE Seguela Bondoukou Savalou ! Komoé ! ! Nzérékoré ! Bouaké Ogun Kenema ! ! Atakpamé Man ! ! Sunyani ! ! Bandama ! Abomey ! St. PaulSanniquellie YAMOUSSOKRO Ibadan Kumasi !\ ! Ho Ikeja ! LIBERIA Guiglo ! ! Bomi ! Volta !\! \! Gagnoa Koforidua Buchanan Sassandra ! ! \! Cotonou PORTO NOVO MONROVIA ! LOMÉ Cess ABIDJAN \! 100 Fish Town ACCRA ! !\ Km ! The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Creation date: 29 Nov. 2013 Sources: UNCS, Natural Earth, ESRI, NGA, OCHA. Feedback: [email protected] www.unocha.org www.reliefweb.int. -

Memoire Le Diplôme De Master Professionnel

N° d’ordre : 06/DSTU/2016 MEMOIRE Présenté à L’UNIVERSITE ABOU BEKR BELKAID-TLEMCEN FACULTE DES SCIENCES DE LA NATURE ET DE LA VIE ET SCIENCES DE LA TERRE ET DE L’UNIVERS DEPARTEMENT DES SCIENCES DE LA TERRE ET DE L’UNIVERS Pour obtenir LE DIPLÔME DE MASTER PROFESSIONNEL Spécialité Géo-Ressources par Meriem FETHI APPORT DE LA GEOLOGIE DAND L’EXPLOITATION DES GISEMENT DE GRANULATS (CAS D’UNE CARRIERE DANS LA REGION D’ADRAR) Soutenu le 30 juin 2016 devant les membres du jury : Mustapha Kamel TALEB, MA (A), Univ. Tlemcen Président Hassina LOUHA, MA (A), Univ. Tlemcen Encadreur Souhila GAOUAR, MA (A), Univ. Tlemcen Examinateur Fatiha HADJI, MA (A), Univ. Tlemcen Examinateur TABLE DES MATIERES Dédicace Remerciement Résumé Abstract BUT ET ORGANISATION DE TRAVAIL A. But de travail ........................................................................................................ 1 B. Méthodologie ....................................................................................................... 1 Chapitre I INTRODUCTION GENERAL I. SITUATION GEOGRAPHIQUE DE LA WILAYA D’ADRAR ........... 2 II. GEOMORPHOLOGIE, HYDROGRAPHIE, CLIMAT ET VEGETATION :.. ........................................................................................ 3 II.1. Géomorphologie : ........................................................................................ 3 II.2. Ressource hydrogéologiques : ..................................................................... 4 II.3. Climatologie et végétation : ........................................................................ -

The Water Use in Agriculture in the Algerian Central Sahara: What Future? Bouchemal S* Department of GTU, RNAMS Laboratory, University of Oum El Bouaghi, Algeria

United Journal of Agricultural Science and Research Review Article Volume 1 The Water Use in Agriculture in the Algerian Central Sahara: What Future? Bouchemal S* Department of GTU, RNAMS Laboratory, University of Oum El Bouaghi, Algeria *Corresponding author: Received: 25 Nov 2020 Copyright: Accepted: 08 Dec 2020 ©2020 Bouchemal S et al., This is an open access article Salah Bouchemal, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons At- Department of GTU, RNAMS Laboratory, University Published: 15 Dec 2020 tribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distri- of Oum El Bouaghi, Algeria, bution, and build upon your work non-commercially. E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Keywords: Bouchemal S. The Water Use in Agriculture in the Al- Water; Irrigation; Foggara; Agriculture; Development; gerian Central Sahara: What Future?. United Journal of Central Sahara; Algeria Agricultural Science and.Reserach. 2020; V1(2): 1-5. 1. Abstract 2.1. The Water Use in Central Sahara The study on the use of water in the Algerian Central Sahara shows In the Central Sahara, agriculture is one of the main sources of in- that this resource has given much hope to the development of ag- come. It obeys two types of water exploitation system, a traditional riculture in this part of Algeria, thanks to a law that has allowed system, which is based on irrigation by foggara, and another called the granting of concessions to the farmers in different parts of the modern, based on the techniques of sinking wells or boreholes but country. This has given rise to several forms of agricultural de- whose charges are very important and therefore do not allow an velopment, each with its own particularities, but everywhere the appreciable extension of the cultivated areas. -

Boofi 6HEEH SIATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY I

RUNIC EVIDENCE OF LAMINOALVEOLAR AFFRICATION IN OLD ENGLISH Tae-yong Pak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 1969 Approved by Doctoral Committee BOOfi 6HEEH SIATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY I 428620 Copyright hy Tae-yong Pak 1969 ii ABSTRACT Considered 'inconsistent' by leading runologists of this century, the new Old English runes in the palatovelar series, namely, gar, calc, and gar-modified (various modi fications of the old gifu and cën) have not been subjected to rigorous linguistic analysis, and their relevance to Old English phonology and the study of Old English poetry has remained unexplored. The present study seeks to determine the phonemic status of the new runes and elucidate their implications to alliteration. To this end the following methods were used: 1) The 60-odd extant Old English runic texts were examined. Only four monuments (Bewcastle, Ruthwell, Thornhill, and Urswick) were found to use the new runes definitely. 2) In the four texts the words containing the new and old palatovelar runes were isolated and tabulated according to their environments. The pattern of distribution was significant: gifu occurred thirteen times in front environments and twice in back environments; cen, eight times front and once back; gar, nine times back; calc, five times back and once front; and gar-modified, twice front. Although cen and gifu occurred predominantly in front environments, and calc and gar in back environments, their occurrences were not complementary. 3) To interpret the data minimal or near minimal pairs with the palatovelar consonants occurring in front or back environments were examined. -

Old English Feet

7. Old English Feet Chris Golston California State University, Fresno 1. Introduction In this chapter I show that the Beowulf poet carefully avoids lines whose halves are identical in terms of stressed (x) and stressless (.) syllables. The half-line (x.x.), for instance, is happily paired with anything but another (x.x.), despite the fact that (x.x.) is by far the commonest half-line type in the poem. Statistical analysis shows that this avoidance is not by chance and suggests that having identical adjacent half-lines is unmetrical in the poem. The same appears to be the case for half-lines identical in weight: a half-line with heavy and light syllables that runs (HLHL) does not pair with one that runs (HLHL). The results are obtained by looking at each and every syllable in the poem, regardless of stress, morphological status, or position within the line. This shows that Beowulf meter strictly regulates every syllable in the poem. Theories that ignore pre-tonic syllables (Bliss 1958), syllables that occur in prefixes (Russom 1987), stressless syllables in general (Keyser 1969, Fabb & Halle 2008), or stress in general (Golston & Riad 2001) cannot account for this fact. An adequate theory of OE meter must include stress, quantity, and the avoidance of identical half-lines. 2. Variation We may begin with a metrical scansion of the first part of the poem, where the first syllable of every lexical root (noun, verb, adjective) is stressed (x) and all others are stressless (.): (1)!Beowulf lines 1-11 Hwat, w" g#r-dena in ge#r-dagum, ! . -

Lexical Phonology and the History of English

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH APRIL McMAHON Department of Linguistics University of Cambridge PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011±4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia # April McMahon 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Times 10/13pt. [ce] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data McMahon, April M. S. Lexical Phonology and the history of English / April McMahon. p. cm. ± (Cambridge studies in linguistics; 91) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0 521 47280 6 hardback 1. English language ± Phonology, Historical. 2. English language ± History. 3. Lexical Phonology. I. Title. II. Series. PE1133.M37 2000 421'.5 ± dc21 99±28845 CIP ISBN 0 521 47280 6 hardback Contents Acknowledgements page xi 1 The roÃle of history 1 1.1 Internal and external evidence 1 1.2 Lexical Phonology and its predecessor 5 1.3 Alternative models 13 1.4 The structure of the book 33 2 Constraining the model: current -

1 Old English Phonology After Our First Few Lessons Using This Language

1 Old English Phonology After our first few lessons using This Language, A River, I’ve decided that you need supplementary materials that are a little bit clearer and more schematic, as well as a little bit more complete. The following pages are intended to supplement the material on pp. 125-132. The Old English Alphabet The Anglo-Saxons acquired the alphabet that they used in manuscripts from Christians who led efforts to convert them from the 580s onward. The Christians, as the inheritors of Roman textual traditions, used the Latin alphabet. When Christian monks began writing down Old English texts, they discovered that Old English included a number of sounds that the Latin alphabet did not represent easily. For this reason, they adapted a few runic characters into the Latin alphabet that they used to represent Old English. A momentary digression about Runes The runic alphabet was used throughout Northern Europe among communities who spoke languages that were part of the larger Germanic language family, but it was an alphabet that was best adapted for carving and inscription on stone, wood, metal, and bone rather than for writing on parchment or vellum. The oldest surviving artifact that certainly reflects a runic text is a bone comb from approximately 150AD found in a bog in Denmark (Looijenga 161). The inscription reads ᚺᚫᚱᛃᚫ: “harja.” The text may mean “warrior,” or “member of the Harii tribe,” or “hair.” Personally, I have always preferred the last interpretation because it seems like an amusingly obvious thing to put on a comb. In any case, the runic alphabets employed single graphical representations for phonemes that Germanic languages had but that Latin did not: <æ> ‘æsh’, which is also the character used in the IPA for the low front vowel phoneme in English /æ/; <þ> ‘thorn’, which represented the phoneme /θ/; <ƿ> ‘wynn’, which represented the phoneme /w/. -

South Algerian EFL Learners' Errors Bachir Bouhania, University Of

South Algerian EFL Learners’ Errors Bachir Bouhania, University of Adrar, Algeria European Conference on Language Learning 2014 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract In higher education, particularly in departments of English, EFL students write essays, and research papers in the target language. Arab learners of English, however, face several difficulties at the morphological, phonetic and phonological, stylistic and syntactic levels. This paper reports on the findings of a corpus study, which analyses the wrong use of the English verb to exist as *to be exist as *is exists, *are existed, *does not exist, and *existness. The corpus consists of more than two thousand exam copies of mid-term, make-up and remedial exams for the academic years ranging between 2003 and 2013.The exams papers concern the fields of Discourse Typology, Linguistics and Sociolinguistics, Phonetics and Phonology. The analysis of the results obtained from the data shows that, although the wrong verb is not used by the majority of students, it is nevertheless significantly found in a number of exam sheets (s=78). Keywords: Error Analysis, Algerian learners, EFL, errors, Intralingual interference, interlanguage, Interlingual interference, linguistic transfer. iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org Introduction At university level, EFL students submit essays, research papers and final projects in English to show accuracy and performance in the target language. They need to master the language and the genres that characterise the various subjects such as civilisation, literature and linguistics. Yet, writing and speaking in English is a complex process for foreign language learners who, unavoidably, make a lot of errors. As part of the learning process (Hyland 2003, Ferris 2002), errors are regular and consistent (Reid, 1993) even if students learn the rules of English grammar (Lalande 1982) Arab EFL learners, on the other side, find difficulties at the phonetic/phonological, morphological and syntactic levels. -

Recommended Resources

Recommended Resources Chapter 1: Studying the History of English An extremely interesting, very readable, and beautifully produced account of the English language: Crystal, David. 2003a. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. The standard reference work on the history of English: The Cambridge History of English. 1992–1999. Vols. I–VI (Vol. I ed. by Richard M. Hogg, Vol. II ed. by Norman Blake, Vol. III ed. by Roger Lass, Vol. IV ed. by Suzanne Romaine, Vol. V ed. by Robert Burchfield, Vol. VI ed. by John Algeo). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Some traditional and more contemporary textbooks of the history of English: Algeo, John. 2010. The Origins and Development of the English Language. Based on the original work of Thomas Pyles. 6th edn. Boston: Thomson-Wadsworth. Barber, Charles, Beal, Joan, and Shaw, Philip A. 2009. The English Language: A Historical Introduction. 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Baugh, Albert C., and Thomas Cable. 2013. A History of the English Language. 6th edn. Boston: Pearson. Gelderen, Elly van. 2014. A History of the English Language. Revised edn. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Gramley, Stephan. 2001. The Vocabulary of World English. London: Arnold. Millward, C.M., and Hayes, Mary. 2011. A Biography of the English Language. 3rd edn. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage. Singh, Ishtla. 2005. The History of English: A Student’s Guide. London: Hodder Arnold. More on English as a global language: Crystal, David. 2006b. English as a Global Language. 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. The most complete contemporary grammars of English: Biber, Douglas, Johansson, Stig, Leech, Geoffrey, Conrad, Susan, and Finegan, Edward. -

Essaie De Presentation

REPUBLIQUE ALGERIEENE DEMOCRATIQUE ET POPULAIRE MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL INSTITUT NATIONAL DES SOLS DE L’IRRIGATION ET DU DRAINAGE ESSAI DE PRESENTATION D’UNE TECHNIQUE D’IRRIGATION TRADITIONNELLE DANS LA WILAYA D’ADRAR : LA « FOGGARA » SOMMAIRE Introduction CHAPITRE -I- 1-1/ Définition d’une foggara 1-2/ Historique CHAPITRE –II- 2-1/ Situation géographique 2-2/ Caractères généraux 2-2-1/ Climatologie i/ température ii/ les vents iii/ la pluviométrie 2-2-2/ Géologie 2-2-3/ Hydrogéologie 2-2-4/ Végétation CHAPITRE –III- 3-1/ Inventaire des foggaras taries 3-2/ Les causes du tarissement des foggaras 3-2-1/ Les problèmes liés à la foggara 3-2-2/ Les problèmes liés à l’exploitation des foggaras. Conclusion Recommandations Bibliographie 1- « Mobilisation de la ressource par le système des foggaras ». Par Hammadi Ahmed El Hadj KOBORI Iwao.1993. 2- «Irrigation et Structure agraire à Tamentit (Touat) » Travaux de l’Institut de Recherches Sahariennes Tome XXI.1962. 3-« Une Oasis à foggaras ‘Tamentit) » Par J. Vallet 1968 4- Inventaires des foggaras (ANRH de la wilaya d’Adrar).2001 5- Etude du tarissement des foggaras dans la wilaya d’Adrar ANRH2003. 6- Les villes du sud, vision du développement durable, Ministère de l’Aménagement du Territoire et de l’Equipement, Alger, 1998, page 46 7- « Les foggaras du Touat » par M. Combés Introduction : Issue du découpage administratif de 1974, la Wilaya d’Adrar s’étend sur la partie Nord du Sud Ouest Algérien, couvrant ainsi une superficie de 427.968 km2 soit 17,97% du territoire national. -

English Phonology and Linguistic Theory: an Introduction to Issues, and to ‘Issues in English Phonology’

Language Sciences 29 (2007) 117–153 www.elsevier.com/locate/langsci English phonology and linguistic theory: an introduction to issues, and to ‘Issues in English Phonology’ Philip Carr a, Patrick Honeybone b,* a De´partement d’anglais, Universite´ de Montpellier III-Paul Vale´ry, Route de Mende, 34199 Montpellier, France b Linguistics and English Language, University of Edinburgh, 14 Buccleuch Place, EH8 9LN, Scotland, UK Abstract Data from the phonology of English has been crucial in the development of phonological and sociophonological theory throughout its recent past. If we had not had English to investigate, we claim, with both its unique and its widely-shared phonological phenomena, linguistic theory might have developed quite differently. In this article, we document some of the ways in which particular English phonological phenomena have driven theoretical developments in phonology and related areas, as a contribution to the history of recent phonological theorising. As we do this, we set in their context the other individual articles in the Special Issue of Language Sciences on ‘Issues in English Phonology’ to which this article is an introduction, explaining both their contents and how they relate to and seek to advance our understanding of the English phonological phenomena in question. Ó 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: English phonology; History of phonological theory; Sociophonology; Vowel shift; Lexical strata; Lenition; Tense–lax 1. Introduction Is it still worth investigating the phonology of English? After all, English is probably the best studied of all languages, so we might wonder whether it can still provide data that is * Corresponding author. -

GE84/230 BR IFIC Nº 2795 Section Spéciale Special Section Sección

Section spéciale Index BR IFIC Nº 2795 Special Section GE84/230 Sección especial Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Date/Fecha : 26.05.2015 Expiry date for comments / Fecha limite para comentarios / Date limite pour les commentaires : 03.09.2015 Description of Columns / Descripción de columnas / Description des colonnes Intent Purpose of the notification Propósito de la notificación Objet de la notification 1a Assigned frequency Frecuencia asignada Fréquence assignée 4a Name of the location of Tx station Nombre del emplazamiento de estación Tx Nom de l'emplacement de la station Tx B Administration Administración Administration 4b Geographical area Zona geográfica Zone géographique 4c Geographical coordinates Coordenadas geográficas Coordonnées géographiques 6a Class of station Clase de estación Classe de station 1b Vision / sound frequency Frecuencia de portadora imagen/sonido Fréquence image / son 1ea Frequency stability Estabilidad de frecuencia Stabilité de fréquence 1e carrier frequency offset Desplazamiento de la portadora Décalage de la porteuse 7c System and colour system Sistema de transmisión / color Système et système de couleur 9d Polarization Polarización Polarisation 13c Remarks Observaciones Remarques 9 Directivity Directividad