32 Euripides's Bacchae in Aeneid Book VII Christine Roughan, 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal Timothy Hanford Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/427 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by TIMOTHY HANFORD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ©2014 TIMOTHY HANFORD All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ronnie Ancona ________________ _______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Dee L. Clayman ________________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer James Ker Joel Lidov Craig Williams Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by Timothy Hanford Advisor: Professor Ronnie Ancona This dissertation explores the relationship between Senecan tragedy and Virgil’s Aeneid, both on close linguistic as well as larger thematic levels. Senecan tragic characters and choruses often echo the language of Virgil’s epic in provocative ways; these constitute a contrastive reworking of the original Virgilian contents and context, one that has not to date been fully considered by scholars. -

Aeneid 7 Page 1 the BIRTH of WAR -- a Reading of Aeneid 7 Sara Mack

Birth of War – Aeneid 7 page 1 THE BIRTH OF WAR -- A Reading of Aeneid 7 Sara Mack In this essay I will touch on aspects of Book 7 that readers are likely either to have trouble with (the Muse Erato, for one) or not to notice at all (the founding of Ardea is a prime example), rather than on major elements of plot. I will also look at some of the intertexts suggested by Virgil's allusions to other poets and to his own poetry. We know that Virgil wrote with immense care, finishing fewer than three verses a day over a ten-year period, and we know that he is one of the most allusive (and elusive) of Roman poets, all of whom wrote with an eye and an ear on their Greek and Roman predecessors. We twentieth-century readers do not have in our heads what Virgil seems to have expected his Augustan readers to have in theirs (Homer, Aeschylus, Euripides, Apollonius, Lucretius, and Catullus, to name just a few); reading the Aeneid with an eye to what Virgil has "stolen" from others can enhance our enjoyment of the poem. Book 7 is a new beginning. So the Erato invocation, parallel to the invocation of the Muse in Book 1, seems to indicate. I shall begin my discussion of the book with an extended look at some of the implications of the Erato passage. These difficult lines make a good introduction to the themes of the book as a whole (to the themes of the whole second half of the poem, in fact). -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

The Thebaid Europa, Cadmus and the Birth of Dionysus

The Thebaid Europa, Cadmus and the birth of Dionysus Caesar van Everdingen. Rape of Europa. 1650 Zeus = Io Memphis = Epaphus Poseidon = Libya Lysianassa Belus Agenor = Telephassa In the Danaid, we followed the descendants of Belus. The Thebaid follows the descendants of Agenor Agenor = Telephassa Cadmus Phoenix Cylix Thasus Phineus Europa • Agenor migrated to the Levant and founded Sidon • But see Josephus, Jewish Antiquities i.130 - 139 • “… for Syria borders on Egypt, and the Phoenicians, to whom Sidon belongs, dwell in Syria.” (Hdt. ii.116.6) The Levant Levant • Jericho (9000 BC) • Damascus (8000) • Biblos (7000) • Sidon (4000) Biblos Damascus Sidon Tyre Jericho Levant • Canaanites: • Aramaeans • Language, not race. • Moved to the Levant ca. 1400-1200 BC • Phoenician = • purple dye people Biblos Damascus Sidon Tyre Agenor = Telephassa Cadmus Phoenix Cylix Thasus Phineus Europa • Zeus appeared to Europa as a bull and carried her to Crete. • Agenor sent his sons in search of Europa • Don’t come home without her! • The Rape of Europa • Maren de Vos • 1590 Bilbao Fine Arts Museum (Spain) Image courtesy of wikimedia • Rape of Europa • Caesar van Everdingen • 1650 • Image courtesy of wikimedia • Europe Group • Albert Memorial • London, 1872. • A memorial for Albert, husband of Queen Victoria. Crete Europa = Zeus Minos Sarpedon Rhadamanthus • Asterius, king of Crete, married Europa • Minos became king of Crete • Sarpedon king of Lycia • Rhadamanthus king of Boeotia The Brothers of Europa • Phoenix • Remained in Phoenicia • Cylix • Founded -

Thebaid 2: Oedipus Descendants of Cadmus

Thebaid 2: Oedipus Descendants of Cadmus Cadmus = Harmonia Aristaeus = Autonoe Ino Semele Agave = Echion Pentheus Actaeon Polydorus (?) Autonoe = Aristaeus Actaeon Polydorus (?) • Aristaeus • Son of Apollo and Cyrene • Actaeon • While hunting he saw Artemis bathing • Artemis set his own hounds on him • Polydorus • Either brother or son of Autonoe • King of Cadmeia after Pentheus • Jean-Baptiste-Camile Corot ca. 1850 Giuseppe Cesari, ca. 1600 House of Cadmus Hyrieus Cadmus = Harmonia Dirce = Lycus Nycteus Autonoe = Aristaeus Zeus = Antiope Nycteis = Polydorus Zethus Amphion Labdacus Laius Tragedy of Antiope • Polydorus: • king of Thebes after Pentheus • m. Nycteis, sister of Antiope • Polydorus died before Labdacus was of age. • Labdacus • Child king after Polydorus • Regency of Nycteus, Lycus Thebes • Laius • Child king as well… second regency of Lycus • Zethus and Amphion • Sons of Antiope by Zeus • Jealousy of Dirce • Antiope imprisoned • Zethus and Amphion raised by shepherds Zethus and Amphion • Returned to Thebes: • Killed Lycus • Tied Dirce to a wild bull • Fortified the city • Renamed it Thebes • Zethus and his family died of illness Death of Dirce • The Farnese Bull • 2nd cent. BC • Asinius Pollio, owner • 1546: • Baths of Caracalla • Cardinal Farnese • Pope Paul III Farnese Bull Amphion • Taught the lyre by Hermes • First to establish an altar to Hermes • Married Niobe, daughter of Tantalus • They had six sons and six daughters • Boasted she was better than Leto • Apollo and Artemis slew every child • Amphion died of a broken heart Niobe Jacques Louis David, 1775 Cadmus = Harmonia Aristeus =Autonoe Ino Semele Agave = Echion Nycteis = Polydorus Pentheus Labdacus Menoecius Laius = Iocaste Creon Oedipus Laius • Laius and Iocaste • Childless, asked Delphi for advice: • “Lord of Thebes famous for horses, do not sow a furrow of children against the will of the gods; for if you beget a son, that child will kill you, [20] and all your house shall wade through blood.” (Euripides Phoenissae) • Accidentally, they had a son anyway. -

Homer the Iliad

1 Homer The Iliad Translated by Ian Johnston Open access: http://johnstoniatexts.x10host.com/homer/iliadtofc.html 2010 [Selections] CONTENTS I THE QUARREL BY THE SHIPS 2 II AGAMEMNON'S DREAM AND THE CATALOGUE OF SHIPS 5 III PARIS, MENELAUS, AND HELEN 6 IV THE ARMIES CLASH 6 V DIOMEDES GOES TO BATTLE 6 VI HECTOR AND ANDROMACHE 6 VII HECTOR AND AJAX 6 VIII THE TROJANS HAVE SUCCESS 6 IX PEACE OFFERINGS TO ACHILLES 6 X A NIGHT RAID 10 XI THE ACHAEANS FACE DISASTER 10 XII THE FIGHT AT THE BARRICADE 11 XIII THE TROJANS ATTACK THE SHIPS 11 XIV ZEUS DECEIVED 11 XV THE BATTLE AT THE SHIPS 11 XVI PATROCLUS FIGHTS AND DIES 11 XVII THE FIGHT OVER PATROCLUS 12 XVIII THE ARMS OF ACHILLES 12 XIX ACHILLES AND AGAMEMNON 16 XX ACHILLES RETURNS TO BATTLE 16 XXI ACHILLES FIGHTS THE RIVER 17 XXII THE DEATH OF HECTOR 17 XXIII THE FUNERAL GAMES FOR PATROCLUS 20 XXIV ACHILLES AND PRIAM 20 I THE QUARREL BY THE SHIPS [The invocation to the Muse; Agamemnon insults Apollo; Apollo sends the plague onto the army; the quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon; Calchas indicates what must be done to appease Apollo; Agamemnon takes Briseis from Achilles; Achilles prays to Thetis for revenge; Achilles meets Thetis; Chryseis is returned to her father; Thetis visits Zeus; the gods con-verse about the matter on Olympus; the banquet of the gods] Sing, Goddess, sing of the rage of Achilles, son of Peleus— that murderous anger which condemned Achaeans to countless agonies and threw many warrior souls deep into Hades, leaving their dead bodies carrion food for dogs and birds— all in fulfilment of the will of Zeus. -

Euripides and Gender: the Difference the Fragments Make

Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Ruby Blondell, Chair Deborah Kamen Olga Levaniouk Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2013 Melissa Karen Anne Funke University of Washington Abstract Euripides and Gender: The Difference the Fragments Make Melissa Karen Anne Funke Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Ruby Blondell Department of Classics Research on gender in Greek tragedy has traditionally focused on the extant plays, with only sporadic recourse to discussion of the many fragmentary plays for which we have evidence. This project aims to perform an extensive study of the sixty-two fragmentary plays of Euripides in order to provide a picture of his presentation of gender that is as full as possible. Beginning with an overview of the history of the collection and transmission of the fragments and an introduction to the study of gender in tragedy and Euripides’ extant plays, this project takes up the contexts in which the fragments are found and the supplementary information on plot and character (known as testimonia) as a guide in its analysis of the fragments themselves. These contexts include the fifth- century CE anthology of Stobaeus, who preserved over one third of Euripides’ fragments, and other late antique sources such as Clement’s Miscellanies, Plutarch’s Moralia, and Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae. The sections on testimonia investigate sources ranging from the mythographers Hyginus and Apollodorus to Apulian pottery to a group of papyrus hypotheses known as the “Tales from Euripides”, with a special focus on plot-type, especially the rape-and-recognition and Potiphar’s wife storylines. -

The Legend of Cadmus and the Logographi Author(S): A

The Legend of Cadmus and the Logographi Author(s): A. W. Gomme Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 33 (1913), pp. 53-72 Published by: The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/624086 . Accessed: 17/01/2015 11:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Hellenic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sat, 17 Jan 2015 11:11:03 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE LEGENDIOF CADMUS AND THE LOGOGRAPHI. I. 1.-FIRST APPEARANCE OF THE PHOENICIAN THEORY. IN an article in the Annual of the British School at Athens 1 I have endeavoured to show that the geography of Boeotia lends no support to the theory that the Cadmeans were Phoenicians. Yet from the fifth century onwards at least, there was a firmly established and, as far as we know, universally accepted tradition that they were-a tradition indeed lightly put aside by most modern scholars as unimportant. -

Meter in Catullan Invective: Expectations and Innovation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Boston University Institutional Repository (OpenBU) Boston University OpenBU http://open.bu.edu Theses & Dissertations Boston University Theses & Dissertations 2015 Meter in Catullan invective: expectations and innovation https://hdl.handle.net/2144/15640 Boston University BOSTON UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Dissertation METER IN CATULLAN INVECTIVE: EXPECTATIONS AND INNOVATION by MICHAEL IAN HULIN WHEELER B.A., University of Florida, 2004 M.A., University of Florida, 2005 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 © Copyright by MICHAEL IAN HULIN WHEELER 2015 Approved by First Reader ______________________________________________________ Patricia Johnson, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Classical Studies Second Reader ______________________________________________________ James Uden, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Classical Studies Third Reader ______________________________________________________ Jeffrey Henderson, Ph.D. William Goodwin Aurelio Professor of Greek Language and Literature Acknowledgements Above all others, I would like to thank my family for their support along the journey towards the completion of my dissertation. I owe the greatest gratitude to my wife, Lis, whose (long-suffering) patience, love, and willingness to keep me on track has been indispensable; to my parents and grandmother, who have been nothing but supportive and encouraging along the way; to my late grandfather and great-uncle, who showed me that getting a doctorate was a possibility (though admittedly the two-years-to- degree record was impossible to match); and finally to Caesar Augustus, the most classically educated dachshund I’ve ever known, and to his loving successor Livia, both of whom are sorely missed. -

Further Responses to Lewis's 'Lost Aeneid'

Inklings Forever: Published Colloquium Proceedings 1997-2016 Volume 8 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Joint Meeting of The Eighth Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Lewis & Friends Article 10 and The C.S. Lewis & The Inklings Society Conference 5-31-2012 Further Responses to Lewis's 'Lost Aeneid' Richard James Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation James, Richard (2012) "Further Responses to Lewis's 'Lost Aeneid'," Inklings Forever: Published Colloquium Proceedings 1997-2016: Vol. 8 , Article 10. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol8/iss1/10 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever: Published Colloquium Proceedings 1997-2016 by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INKLINGS FOREVER, Volume VIII A Collection of Essays Presented at the Joint Meeting of The Eighth FRANCES WHITE EWBANK COLLOQUIUM ON C.S. LEWIS & FRIENDS and THE C.S. LEWIS AND THE INKLINGS SOCIETY CONFERENCE Taylor University 2012 Upland, Indiana Further Responses to Lewis’s ‘Lost Aeneid’ Richard James James, Richard. “Further Responses to Lewis’s ‘Lost Aeneid’.” Inklings Forever 8 (2012) www.taylor.edu/cslewis 1 Further Responses to Lewis’s ‘Lost Aeneid’ Richard James For almost fifty years, since his death Let me begin with a disclaimer in 1963, C.S. -

Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 1

Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 1 The following characters are described in the pages that follow the list. Page Order Alphabetical Order Aeolus 2 Achaemenides 8 Neptune 2 Achates 2 Achates 2 Aeolus 2 Ilioneus 2 Allecto 19 Cupid 2 Amata 17 Iopas 2 Andromache 8 Laocoon 2 Anna 9 Sinon 3 Arruns 22 Coroebus 3 Caieta 13 Priam 4 Camilla 22 Creusa 6 Celaeno 7 Helen 6 Coroebus 3 Celaeno 7 Creusa 6 Harpies 7 Cupid 2 Polydorus 7 Dēiphobus 11 Achaemenides 8 Drances 30 Andromache 8 Euryalus 27 Helenus 8 Evander 24 Anna 9 Harpies 7 Iarbas 10 Helen 6 Palinurus 10 Helenus 8 Dēiphobus 11 Iarbas 10 Marcellus 12 Ilioneus 2 Caieta 13 Iopas 2 Latinus 13 Juturna 31 Lavinia 15 Laocoon 2 Lavinium 15 Latinus 13 Amata 17 Lausus 20 Allecto 19 Lavinia 15 Mezentius 20 Lavinium 15 Lausus 20 Marcellus 12 Camilla 22 Mezentius 20 Arruns 22 Neptune 2 Evander 24 Nisus 27 Nisus 27 Palinurus 10 Euryalus 27 Polydorus 7 Drances 30 Priam 4 Juturna 31 Sinon 2 An outline of the ACL presentation is at the end of the handout. Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 2 Aeolus – with Juno as minor god, less than Juno (tributary powers), cliens- patronus relationship; Juno as bargainer and what she offers. Both of them as rulers, in contrast with Neptune, Dido, Aeneas, Latinus, Evander, Mezentius, Turnus, Metabus, Ascanius, Acestes. Neptune – contrast as ruler with Aeolus; especially aposiopesis. Note following sympathy and importance of rhetoric and gravitas to control the people. Is the vir Aeneas (bringing civilization), Augustus (bringing order out of civil war), or Cato (actually -

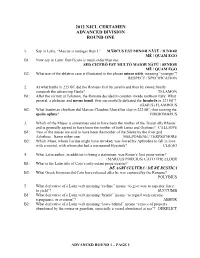

2012 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2012 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Say in Latin, “Marcus is younger than I.” MĀRCUS EST MINOR NĀTŪ / IUNIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B1: Now say in Latin: But Cicero is much older than me. SED CICERŌ EST MULTŌ MAIOR NĀTŪ / SENIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B2: What use of the ablative case is illustrated in the phrase minor nātū, meaning “younger”? RESPECT / SPECIFICATION 2. At what battle in 225 BC did the Romans first by javelin and then by sword finally vanquish the advancing Gauls? TELAMON B1: After the victory at Telamon, the Romans decided to counter-invade northern Italy. What general, a plebeian and novus homō, first successfully defeated the Insubrēs in 223 BC? (GAIUS) FLAMINIUS B2: What Insubrian chieftain did Marcus Claudius Marcellus slay in 222 BC, thus earning the spolia opīma? VIRIDOMARUS 3. Which of the Muses is sometimes said to have been the mother of the Trojan ally Rhesus and is generally agreed to have been the mother of both Linus and Orpheus? CALLIOPE B1: Two of the muses are said to have been the mother of the Sirens by the river god Achelous. Name either one. MELPOMENE / TERPSICHORE B2: Which Muse, whom Tacitus might have invoked, was forced by Aphrodite to fall in love with a mortal, with whom she had a son named Hyacinth? CL(E)IO 4. What Latin author, in addition to being a statesman, was Rome’s first prose writer? (MARCUS PORCIUS) CATO THE ELDER B1: What is the Latin title of Cato’s only extant prose treatise? DĒ AGRĪ CULTŪRĀ / DĒ RĒ RUSTICĀ B2: What Greek historian did Cato have released after he was captured by the Romans? POLYBIUS 5.