The Essential Ingredient for Liberty and Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hoover Institution Newsletter Spring 2004

HOOVER INSTITUTION SPRING 2004 NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER FEDERAL OFFICIALS, JOURNALISTS, HOOVER FELLOWS HOOVER, SIEPR SHARE DISCUSS DOMESTIC AND WORLD AFFAIRS $5 MILLION GIFT AT BOARD OF OVERSEERS MEETING IN HONOR OF GEORGE P. SHULTZ ecretary of State Colin Powell dis- he Annenberg Foundation has cussed the importance of human granted Stanford University $5 Srights,democracy,and the rule of law Tmillion to honor former U.S. secre- when he addressed the Hoover Institution tary of state George P. Shultz. Board of Overseers and guests on Febru- The Hoover Institution will receive $4 ary 23 in Washington, D.C. million to endow the Walter and Leonore Powell told the group of more than 200 Annenberg Fund in honor of George P. who gathered to hear his postluncheon talk Shultz, which will support the Annenberg that worldwide political and economic Distinguished Visiting Fellow. conditions present not only problems but The Stanford Institute for Economic also great opportunities to share American Policy Research (SIEPR) will receive $1 values. million for the George P. Shultz Disserta- Other speakers during the day included tion Support Fund, which supports empir- Dinesh D’Souza, the Robert and Karen ical research by graduate students working Rishwain Research Fellow, who discussed on dissertations oriented toward problems Colin Powell the future of American conservativism. of economic policy. Reflecting on the legacy of Ronald ing values and virtues that have sustained “In all of his capacities, George has Reagan’s presidency, he pointed to endur- American society for more than 200 years. given unstintingly to this institution over continued on page 8 continued on page 4 PRESIDENT BUSH NAMES HENRY S. -

Hillsdale College Freedom Library Catalog

Hillsdale College Freedom Library Catalog Books from Hillsdale College Press, Back Issues of Imprimis, Seminar CDs and DVDs THOMAS JEFFERSON | ANTHONY FRUDAKIS, SCULPTOR AND ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ART, HILLSDALE COLLEGE CARSON BHUTTO YORK D'SOUZA STRASSEL WALLACE HANSON PESTRITTO GRAMM ARNN GOLDBERG MORGENSON GILDER JACKSON THATCHER RILEY MAC DONALD FRIEDMAN Hillsdale College Freedom Library Catalog illsdale College is well known for its unique independence and its commitment to freedom and the liberal arts. It rejects the huge federal and state taxpayer subsidies that go to support other American colleges and universities, relying instead on the voluntary Hcontributions of its friends and supporters nationwide. It refuses to submit to the unjust and burdensome regulations that go with such subsidies, and remains free to continue its 170-year-old mission of offering the finest liberal arts education in the land. Its continuing success stands as a powerful beacon to the idea that independence works. This catalog of books, recordings, and back issues of Imprimis makes widely available some of the best writings and speeches around, by some of the smartest and most important people of our time. These writings and speeches are central to Hillsdale’s continuing work of promoting freedom, supporting its moral foundations, and defending its constitutional framework. Contents Hillsdale College Press Books .................................................... 1 Imprimis ...................................................................... 5 Center -

Economics-For-Real-People.Pdf

Economics for Real People An Introduction to the Austrian School 2nd Edition Economics for Real People An Introduction to the Austrian School 2nd Edition Gene Callahan Copyright 2002, 2004 by Gene Callahan All rights reserved. Written permission must be secured from the publisher to use or reproduce any part of this book, except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles. Published by the Ludwig von Mises Institute, 518 West Magnolia Avenue, Auburn, Alabama 36832-4528. ISBN: 0-945466-41-2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dedicated to Professor Israel Kirzner, on the occasion of his retirement from economics. My deepest gratitude to my wife, Elen, for her support and forbearance during the many hours it took to complete this book. Special thanks to Lew Rockwell, president of the Ludwig von Mises Institute, for conceiving of this project, and having enough faith in me to put it in my hands. Thanks to Jonathan Erickson of Dr. Dobb’s Journal for per- mission to use my Dr. Dobb’s online op-eds, “Just What Is Superior Technology?” as the basis for Chapter 16, and “Those Damned Bugs!” as the basis for part of Chapter 14. Thanks to Michael Novak of the American Enterprise Insti- tute for permission to use his phrase, “social justice, rightly understood,” as the title for Part 4 of the book. Thanks to Professor Mario Rizzo for kindly inviting me to attend the NYU Colloquium on Market Institutions and Eco- nomic Processes. Thanks to Robert Murphy of Hillsdale College for his fre- quent collaboration, including on two parts of this book, and for many fruitful discussions. -

The Economics of Liberty

The Economics of Liberty Edited by Llewellyn H. Rockwell The Ludwig von Mises Institute Auburn, Alabama 36849 The Ludwig von Mises Institute gratefully acknowledges the Patrons whose generosity made the publication of this book possible: a.p. Alford, III James W. Frevert Robert E. Miller Morgan Adams, Jr. John B. Gardner A. Minis, Jr. The Adams Fund Martin Garfinkel Dr. K. Lyle Moore Anonymous (4) Thomas E. Gee Dr. Francis Powers Dr. J.e. Arthur Bernard G. Geuting Donald Mosby Rembert Joe Baldinger W.B. Grant V.S. Boddicker AANGS Co. James M. Rodney The Boddicker W. Grover Catherine Dixon Roland Investment Co. Freeway Fasteners Sheldon Rose Brenda Bretan Dr. Robert M. Hansen Dwight Rounds Franklin M. Buchta Harry H. Hoiles Gary G. Schlarbaum E.O. Buck Charles Hollinger Mrs. Harold B. Chait T.D. James Stanley Schmidt J.E. Coberly, Jr. G.E. Johnson Charles K. Seven William B. Coberly, Jr. Michael L. Keiser Vincent J. Severini Coberly-West Co. John F. Kieser E.D. Shaw, Jr. Dr. Everett S. Coleman H.E. King Shaw Oxygen Co. Christopher P. Condon The M.H. King Russell Shoemaker Morgan Cowperthwaite Foundation Shoemaker's Candies Charles G. Dannelly W.H. Kleiner Abe Siemens Carl A. Davis Julius and Emma Clyde A. Sluhan Davls-Lynch, Inc. Kleiner Foundation Robert E. Derges Dr. Richard J. Donald R. Stewart John Dewees Kossmann David F. Swain, Jr. William A. Diehl John L. Kreischer Walter F. Taylor Robert H. Krieble Robert T. Dofflemyer Dr. Benjamin H. Krteble Associates Dr. William A. Dunn Thurman Norma R. Lineberger Dunn Capital C.S. -

Developing a Suitable Water Allocation Law for Pennsylvania

Volume 17 Issue 1 Article 1 2006 Developing a Suitable Water Allocation Law for Pennsylvania Joseph W. Dellapenna Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/elj Part of the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph W. Dellapenna, Developing a Suitable Water Allocation Law for Pennsylvania, 17 Vill. Envtl. L.J. 1 (2006). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/elj/vol17/iss1/1 This Symposia is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Environmental Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Dellapenna: Developing a Suitable Water Allocation Law for Pennsylvania VILLANOVA ENVIRONMENTAL LAW JOURNAL VOLUME XVII 2006 NUMBER 1 DEVELOPING A SUITABLE WATER ALLOCATION LAW FOR PENNSYLVANIA BY JOSEPH W. DELLAPENNA* I. OVERVIEW In many respects, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is unu- sual. One of the original thirteen colonies, Pennsylvania continues to adhere more closely to the original common law legal system the colonists brought over in 1683. For example, plaintiffs in Penn- sylvania still must denominate a complaint in the lowest level courts as sounding either in assumpsit (contract) or in trespass (tort),' something few, if any, other states still require. Another unusual feature of Pennsylvania is that it sprawls across large parts of three major watersheds-the Delaware, the Ohio and the Susquehanna- as well as several smaller watersheds. Because of this geography, major water crises seem seldom to affect more than one-third of the Commonwealth at a time. -

Extensions of Remarks

1336 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS January 30, 1980 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS TRIBUTE TO ARETTA CRITICS SAY ILL-ADVISED SPENDING OF OIL aside from oil, these duffcountries-mTgfi.f BARRINGER . FuNDs HURTS ARAB S~IETY. be building white elephanf.s. <By Youssef M. Ibrahim> The rapid modernization taking place in the Gulf, the vast expansion of the school LoNDON, Jan. 27~-Economic experts on HON. GERALD B. H. SOLOMON the Persian Gulf are warning increasingly system and of social welfare have not been OF NEW YORK matched by any degree of pcilitica1 liberal that overly ~bitious plans, bad advice, ization. So, while a new generation is grow IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES little experience and hurried spending in the Arab oil-producing countries have cre ing up better educated and more ambitious, Wednesday, January 30, 1980 ated a force that is tearing at the social it is deprived of participating in the deci- • sionmaking process. • Mr. SOLOMON. Mr. Speaker, on fabric of these conservative Arab nations February 2 the people of Poestenkill, and distorting their economies. DISSIDENT'S BOOK IS BANNED. N.Y., will be paying tribute to one of The warnings are not new. But now they "They send us abroad; they give us the New York State's most dedicated are voiced by a growing chorus of Arab tech- best education money can buy, but when we . · nocrats in such places as Qatar, the United come home with our ·degrees from Harvard · public servants, Aretta Barringer. For Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and or Cambridge it is only to find out they are 52 years, until her decision not to seek Bahrain. -

God Wills It: Presidents and the Political Use of Religion David O

God Wills It: Presidents and the Political Use of Religion David O’Connell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 David O’Connell All rights reserved ABSTRACT God Wills It: Presidents and the Political Use of Religion David O’Connell How have American presidents used religious rhetoric? Has it helped them achieve their goals? Why or why not? These are the main questions this dissertation attempts to grapple with. I begin my study by developing a typology of presidential religious rhetoric that consists of three basic styles of speech. Ceremonial religious rhetoric is meant to capture those times when a president uses religious language in a broad sense that is appropriate for the occasion. Examples would include holiday addresses and funeral eulogies. I label a second variant of religious rhetoric comforting and calming. A president will frequently use religious rhetoric as he tries to shepherd the country through the difficult aftermath of a terrorist attack, a natural disaster or a riot. The final kind I have called instrumental. A president uses instrumental religious rhetoric when he makes an argument founded on religious concepts or beliefs in an attempt to convince interested parties to support a goal of his, such as passing a piece of legislation. The majority of the project focuses on this last type. I propose a strict set of coding rules for both identifying when instrumental religious rhetoric has appeared and for gauging its possible impact. My measures of potential effectiveness focus on the president’s three most important relationships- his relationship with the public, his relationship with the media and his relationship with Congress. -

Kansassampler.Com 1-800-645-5409 [email protected]

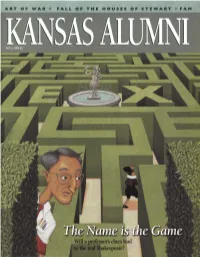

ART OF WAR L FALL OF THE HOUSES OF STEWART FAM me Visit our website where the latest KU merchandise is available online. KansasSampler.com 1-800-645-5409 [email protected] ' % Topeka 9548 Antioch, Overland Park vlall, Missi Town Center Plaza, Leawood KANSAS ALUMNI CONTENTS FEATURES 20 FIRST WORD Candid Combat The editor's tun Glenn Kappelman knew his battlefield duty in World War II would give him a frontline view oj history. Fifty years later his photographs do the same for us. By Steven Hill 26 By Any Other Name Why is retired chemistry professor Albert Burgstahler combing Shakespeare's sonnets and plays for clues to the works' true author? Because they're there. By Chris Lazzarino Cover illustration by Christine M. Schneider 32 Going, Going, Gone? The decline of Stewart Avenue, once a haven of Greek life, is only one of the challenges that make this a pivotal year for KU's fraternities and sororities. By Chris Lazzarino Page 32 VOLUME 98 NO. 5, 2000 KANSAS ALUMNI Put Your We ve spent our Uv§s building the Herbarium into Trust a valuable resource for KU qr InKU tire region. This gift allows us to continue our involvement by contribute As a boy, KU alumnus Ronald L. McGregor, Ph.D., became fasci- to the future success of ttm facility." nated by the varied and abundant — Ronald & Dorothy McGregor plant life on his grandfather's ranch. His youthful enthusiasm grew into a 42-year career at KU. As director of the Herbarium at KU from 1950 to 1989, he guided the growth of the Herbarium's collection of flora to become the largest in the region, including more than 400,000 different spec- imens. -

Climate Disruption, the Washington Consensus, and Water Law Reform

Dellapenna final CLIMATE DISRUPTION, THE WASHINGTON CONSENSUS, AND WATER LAW REFORM ∗ Joseph W. Dellapenna I. INTRODUCTION The planet today is undergoing disruptive climate change.1 As one study found, after nearly a millennium of a slow but steady cooling trend, the twentieth century has seen a dramatic upsurge in average global temperatures.2 For some years, farmers have experienced measurably longer growing seasons in the Northern Hemisphere.3 These changes—which now seem indisputably to result from human activity4—will have vastly altered precipitation patterns around the ∗ Professor of Law, Villanova University. B.B.A., 1965, University of Michigan; J.D., 1968, Detroit College of Law; LL.M. in International and Comparative Law, 1969, George Washington University; LL.M. in Environmental Law, 1974, Columbia University. Professor Dellapenna served as Rapporteur of the Water Resources Committee of the International Law Association, and in that capacity led the drafting of the Berlin Rules on Water Resources (2004). He is also Director of the Model Water Code Project of the American Society of Civil Engineers. 1. See Dimmock v. Sec’y of State for Educ. & Skills, [2008] All E.R. 367, ¶ 17 (Q.B.) (finding that substantial scientific research supports the conclusion that global temperatures have been steadily rising for last fifty years as result of man-made emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide); Climate Change: Understanding the Degree of the Problem: Hearing Before H. Comm. on Gov’t Reform, 109th Cong. 87–89 (2006) (statement of Thomas Karl, Director, National Climatic Data Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) (discussing climate models and noting that human influences affect climate changes, which will include “changes in extremes of temperature and precipitation, decreases in seasonal and perennial snow and ice extent, sea level rise, and increases in hurricane intensity and related heavy and extreme precipitation”); Climate Change: Hearing Before S. -

Evolution and the Holy Ghost of Scopes: Can Science Lose the Next Round? Stephen A

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters Spring 2007 Evolution and the Holy Ghost of Scopes: Can Science Lose the Next Round? Stephen A. Newman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation 8 Rutgers J. L. & Religion 11 (2007) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. RUTGERS JOURNAL OF LAW AND RELIGION Volume 8.2 Spring 2007 EVOLUTION AND THE HOLY GHOST OF SCOPES : CAN SCIENCE LOSE THE NEXT ROUND? By: Stephen A. Newman* The society that allows large numbers of its citizens to remain uneducated, ignorant, or semiliterate squanders its greatest asset, the intelligence of its people. 1 A theory gains acceptance in science not through the power of its adherents to persuade a legislature, but through its intrinsic ability to persuade the discipline at large. 2 Today, we are seeing hundreds of years of scientific discovery being challenged by people who simply disregard facts that don’t happen to agree with their agenda. Some call it pseudo-science, others call it faith-based science, but when you notice where this negligence tends to take place, you might as well call it “political science.” 3 I. IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH4 Two decades ago, in Edwards v. Aguillard , the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional a Louisiana law that conditioned the teaching of evolution in the public schools * Professor of Law, New York Law School 1 DIANE RAVITCH , LEFT BACK : A CENTURY OF BATTLES OVER SCHOOL REFORM 466 (2000). -

Summer 2019 the FIRST FORTY-FIVE

From: Vol. 1, No. 1—Fall | Winter 1974 To: Vol. 45, Nos. 1 & 2—Spring | Summer 2019 THE FIRST FORTY-FIVE YEARS 1 2 1974, Vol. I, No. 1 – Fall / Winter Articles: * A Note on G. K.C. (Reginald Jebb) * An Everlasting Man (Maurice B. Reckitt) * Chesterton and the Man in the Forest (Leo A. Hetzler) * Chesterton on the Centenary of His Birth (Elena Guseva) * Chesterton as an Edwardian Novelist (John Batchelor) * To Gilbert K. Chesterton, a poem (Lewis Filewood) News & Comments: * Letter from Secretary of the Chesterton Society (1. Reviewing centenary year; 2. Announcing meeting of Chesterton Society) * Letter from Secretary of the H.G. Wells Society (Wants to exchange journals with the Chesterton Society) * Note about books: G.K. Chesterton: A Centenary Appraisal by John Sullivan; G. K. Chesterton by Lawrence J. Clipper; G. K. Chesterton: Critical Judgments by D.J. Conlon, and The Medievalism of Chesterton by P.J. Mroczkowski * Spode House Review announcement: publishing of the Chesterton Centenary Conference proceedings * Notes on Articles: “Some Notes on Chesterton” (CSL: The Bulletin of the New York C.S. Lewis Society, May 1974); “Chesterton on Dickens: The Legend and the Reality,” (Dickens Study Newsletter, June 1974); “Chesterton’s Colour Imagery in The Man Who Was Thursday” (Columbia University Pastel Essays Series, September 1974); “Chesterton, Viejo Amigo” (Incunable No. 297, September 1974-spanish); “Gilbert Keith Chesterton: A Fond Tribute” (Thought, XXVI, July 1974, Delhi, India) * Note on: Chesterton Centenary Conference at Notre Dame College of Education in Glasgow, by the Scottish Catholic Historical Association, September 1974 * Note on: Chesterton Conference at Gonzaga University, Spokane, WA, October 1974 * Letter from: John Fenlon Donnely, President of Donnely Mirrors on the Conference at Notre Dame College, Glasgow * Note on Adrian Cunningham (U. -

Vol. 37, No. 20, March 8, 1989 University of Michigan Law School

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Res Gestae Law School History and Publications 1989 Vol. 37, No. 20, March 8, 1989 University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.umich.edu/res_gestae Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation University of Michigan Law School, "Vol. 37, No. 20, March 8, 1989" (1989). Res Gestae. Paper 291. http://repository.law.umich.edu/res_gestae/291 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School History and Publications at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Res Gestae by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Eastern: The Official Airline of the National Federalist Society Vol. 37 No. 20 The University of Michigan Law School March 8 , 1989 Federalists to Convene in Ann Arbor By Jerome Pinn panel wtJJ assemble to discuss "The Idea of Government. and Professor Frederick moderator. will be discussed by University The Federallst Society will be holding Property.· Mr. Tom Bethell. a syndicated Schauer of Michigan Law School. of Michigan Law School Dean Lee C. Its Eighth Annual Nallonal Syposium on columnist. will serve as moderator. Panel A third panel will discuss "Regulation Bollinger. Judge Frank H. Easterbrook, Law and Public Polley at the University of participants Include Professor Richard and Property: Allies or Enemies?" Judge from the Seventh Circuit U.S. Court of ~tichigan Law School on March l Oth and Epstein.