PDF File Created from a TIFF Image by Tiff2pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 168 Friday, 30 December 2005 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising and Information

Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 168 Friday, 30 December 2005 Published under authority by Government Advertising and Information Summary of Affairs FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT 1989 Section 14 (1) (b) and (3) Part 3 All agencies, subject to the Freedom of Information Act 1989, are required to publish in the Government Gazette, an up-to-date Summary of Affairs. The requirements are specified in section 14 of Part 2 of the Freedom of Information Act. The Summary of Affairs has to contain a list of each of the Agency's policy documents, advice on how the agency's most recent Statement of Affairs may be obtained and contact details for accessing this information. The Summaries have to be published by the end of June and the end of December each year and need to be delivered to Government Advertising and Information two weeks prior to these dates. CONTENTS LOCAL COUNCILS Page Page Page Albury City .................................... 475 Holroyd City Council ..................... 611 Yass Valley Council ....................... 807 Armidale Dumaresq Council ......... 478 Hornsby Shire Council ................... 614 Young Shire Council ...................... 809 Ashfi eld Municipal Council ........... 482 Inverell Shire Council .................... 618 Auburn Council .............................. 484 Junee Shire Council ....................... 620 Ballina Shire Council ..................... 486 Kempsey Shire Council ................. 622 GOVERNMENT DEPARTMENTS Bankstown City Council ................ 489 Kogarah Council -

Planning Proposal

Planning Proposal Zoning & minimum lot size changes for Culcairn November 2020 Prepared for Greater Hume Council Habitat Planning 409 Kiewa Street SOUTH ALBURY NSW 2640 p. 02 6021 0662 e. [email protected] w. habitatplanning.com.au Document Control Version Date Purpose Approved A 14/05/20 Draft for client review WH B 09/06/20 Final for Council endorsement WH C 27/11/20 Revised final post-Gateway WH The information contained in this document produced by Habitat Planning is solely for the use of the person or organisation for which it has been prepared and Habitat Planning undertakes no duty to or accepts any responsibility to any third party who may rely upon this document. All rights reserved. No section or element of this document may be removed from this document, reproduced, electronically stored or transmitted in any form without the written permission of Habitat Planning. © 2020 Habitat Planning Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................ 1 PART 1. Intended outcomes ..................................................................................................... 2 PART 2. Explanation of the provisions ...................................................................................... 4 PART 3. Justification ................................................................................................................. 5 Section A. Need for the planning proposal ................................................................ -

Albury-Wodonga Area Consultative Committee 4

68%0,66,21727+( +286(2)5(35(6(17$7,9(6¶ 67$1',1*&200,77(( 21 35,0$5<,1'8675,(6$1' 5(*,21$/6(59,&(6,15(63(&7 2),76,148,5<,172 ,1)5$6758&785($1'7+( '(9(/230(172)$8675$/,$¶6 5(*,21$/$5($6 35(3$5('%< $/%85<:2'21*$$5($&2168/7$7,9(&200,77(( 0$< INFRASTRUCTURE CONTENTS Page SUMMARY OF ISSUES AND RECOMMENDATIONS. i DETAILED REPORT A. INTRODUCTION 1 B. ROLE OF THE ALBURY-WODONGA AREA CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE 4 C. ALBURY-WODONGA’S REGIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE 8 D. SLIGHTLY-REVISED SUBMISSION ORIGINALLY PROVIDED TO THE SENATE EMPLOYMENT, EDUCATION AND TRAINING REFERENCES COMMITTEE REGARDING REGIONAL EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT – JUNE, 1998. 14 APPENDICES. I. Albury-Wodonga Area Consultative Committee 10 II. Investment Albury Wodonga – Economic Indicators 11 III. Development Organisations In And/Or Relevant To Albury-Wodonga - - As at Mid – 1996; 12 - As at Mid – 1999. 13 SUMMARY OF ISSUES A. TERMS OF REFERENCE “Deficiencies in infrastructure which currently impede development in Australia’s regional areas.” Comments - - university courses are still inadequate in Albury-Wodonga, even though two major universities are present. Our per capita student enrolments are still lower than for other major regional centres; - the regular withdrawal of public services can mean significant travel times for users and consequent higher costs. It also means loss of income from often-skilled employees leaving the area; - the tendency by Commonwealth, NSW and Victorian governments to locate regional offices away from state border areas (the “360 degrees syndrome”) - even if Albury-Wodonga is a more appropriate and larger location; - this heading could be taken to also include situations where regional areas’ infrastructure lags behind that in capital cities. -

Walbundrie Whereabouts Term 2

WALBUNDRIE PUBLIC SCHOOL Culcairn Road Newsletter WALBUNDRIE NSW 2642 Term 2 – Week 5 Phone: 6029 9004 [email protected] 1 June 2018 E: [email protected] Shooting Hoops Our School Leaders learnt Through the funding provided by the Sporting Schools Grants, we have heaps at the GRIP Leadership begun having sessions each week with Basketball Australia and coach Conference Helen. These sessions will be held Mondays and Wednesday afternoons every week until Week 9. GRIP Leadership On Monday 28 May, Lilly and Olivia attended the GRIP Leadership Conference in Albury. The girls had the opportunity to learn what makes a good leader and how to make positive change in their school. Check out their report on page 2. RPSSA Cross Country Congratulations to Lilly, who will be representing our Walbundrie Small School Network at the Riverina Cross Country in Gundagai on Thursday 14 June. Well done, Lilly, we wish you all the best of luck! Upcoming Events PSSA Netball Monday 11 June Olivia and Lilly represented the Walbundrie Small Schools Network in QUEEN’S BIRTHDAY the PSSA Netball Knock-out competition. The team was successful in both of their games and is now onto the next level, which should be held Thursday 14 June before the end of term. Congratulations girls! RPSSA Cross Country Down the Rabbit Hole We Went! Monday 18 June It was awesome to see everyone all dressed up for our Book Fair and Library Visit 9:30am Mad Hatter’s Tea Party on Tuesday. Thank you so much to all our Friday 29 June parents for the delicious treats that were sent it, the kids had a fantastic Reports home to parents time! Tuesday 3 July Even Teachers Learn SRPSSA Athletics Carnival As teachers, we are constantly learning to refine our teaching practice Friday 6 July and knowledge. -

Greater Hume Shire Visitor Experience Plan 2014 - 2018 Contact

GREATER HUME SHIRE VISITOR EXPERIENCE PLAN 2014 - 2018 Contact: Kerrie Wise, Tourism and Promotions Officer [email protected] 02 6036 0186 0448 099 536 PO Box 99, 39 Young Street HOLBROOK NSW 2644 © Copyright, Greater Hume Shire Council, December 2013. This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under Copyright Act 1963, no part may be reproduced without written permission of the Greater Hume Shire Council. Document Information ECO.STRAT.0001.002 Last Saved December 2013 Last Printed December 2013 File Size 1189kb Disclaimer Neither Greater Hume Shire Council nor any member or employee of Greater Hume Shire Council takes responsibility in any way whatsoever to any person or organisation (other than that for which this report has been prepared) in respect of the information set out in this report, including any errors or omissions therein. In the course of our preparation of this report, projections have been prepared on the basis of assumptions and methodology which have been described in the report. It is possible that some of the assumptions underlying the projections may change. Nevertheless, the professional judgement of the members and employees of Greater Hume Shire Council have been applied in making these assumptions, such that they constitute an understandable basis for estimates and projections. Beyond this, to the extent that the assumptions do not materialise, the estimates and projections of achievable results may vary. Greater Hume Shire Council – Visitor Experience Plan - 2014 - 2018 2 ECO.STRAT.0001.002 -

Gazette No 145 of 19 September 2003

9419 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEWNew SOUTH South Wales WALES Electricity SupplyNumb (General)er 145 AmendmentFriday, (Tribunal 19 September and 2003 Electricity Tariff EqualisationPublished under authority Fund) by cmSolutions Regulation 2003LEGISLATION under the Regulations Electricity Supply Act 1995 Her Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has made the following Regulation Newunder South the WalesElectricity Supply Act 1995. Electricity Supply (General) Amendment (Tribunal and Electricity TariffMinister for Equalisation Energy and Utilities Fund) RegulationExplanatory note 2003 The object of this Regulation is to prescribe 30 June 2007 as the date on which Divisions under5 and 6the of Part 4 of the Electricity Supply Act 1995 cease to have effect. ElectricityThis Regulation Supply is made Act under 1995 the Electricity Supply Act 1995, including sections 43EJ (1), 43ES (1) and 106 (the general regulation-making power). Her Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has made the following Regulation under the Electricity Supply Act 1995. FRANK ERNEST SARTOR, M.P., Minister forfor EnergyEnergy and and Utilities Utilities Explanatory note The object of this Regulation is to prescribe 30 June 2007 as the date on which Divisions 5 and 6 of Part 4 of the Electricity Supply Act 1995 cease to have effect. This Regulation is made under the Electricity Supply Act 1995, including sections 43EJ (1), 43ES (1) and 106 (the general regulation-making power). s03-491-25.p01 Page 1 C:\Docs\ad\s03-491-25\p01\s03-491-25-p01EXN.fm -

List of S2 Retail Licence Holders for RCU Website As at 14 July 2021

List of retail shops licensed to supply Schedule 2 substances under the NSW Poisons and Therapeutic Goods Act 1966 Licence Name Address State Postcode No S2R1004 JAMIESON, Linda Bate's General Store, 2 Bate Street, CENTRAL TILBA NSW 2546 S2R1005 CACCAVIELLO, Phillip Lucky Phil's Budget-Rite, 53-55 Murray Street, TOOLEYBUC NSW 2736 S2R1011 JACKSON, Lexie 44 Morago Street, MOULAMEIN NSW 2733 S2R1012 WORRALL, Ernest Worrall's Coopernook Store, 23 Macquarie Street, COOPERNOOK NSW 2426 S2R1013 MANNING, Mark Thredbo Health and Beauty, Shop 6 Squatters Run, Mowamba Place, THREDBO NSW 2625 S2R1014 LOWELL, Melissa Bundarra General Store, 30-32 Bendemeer Street, BUNDARRA NSW 2359 S2R1015 DAVIES, Joy Joy's Shop, Middle Beach Road, LORD HOWE ISLAND NSW 2898 S2R1019 GREEN, Peter Deepwater Supermarket, 70 Tenterfield Street, DEEPWATER NSW 2371 S2R1021 JACKSON, Mavis Lorraine TJ’s Outback Trading, 1 Silver City Highway, TIBOOBURRA NSW 2880 S2R1024 BELL, Wendy Ann Long Flat Shop, 5019 Oxley Highway, LONG FLAT NSW 2446 S2R1030 MCKAY, Georgia Eungai Rail General Store, 8-10 Station Street, EUNGAI RAIL NSW 2441 S2R1033 DAVIES, Sandra Ann Mathoura Pharmacy Depot, 24A Livingstone Street, MATHOURA NSW 2710 S2R1037 QUINN, Cathleen Jean The Channon General Store, 7 Standing Street, THE CHANNON NSW 2480 S2R1041 CURRELL, Yvonne Campbell & Freebairn, 38 Albury Street, ASHFORD NSW 2361 S2R1045 BRAYSHAW, Fiona Adaminaby Store, 10-12 Denison Street, ADAMINABY NSW 2629 S2R1047 TROUNSON, Richard Capertree General Store, 44 Castlereagh Highway, CAPERTEE NSW 2846 S2R1049 -

Walbundrie Whereabouts in Our Newsletter and the School Website

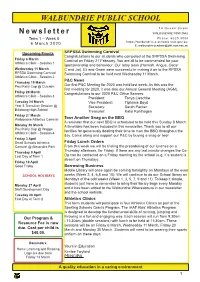

WALBUNDRIE PUBLIC SCHOOL 14 Queen Street Newsletter WALBUNDRIE NSW 2642 Term 1 – Week 6 Phone: 6029 9004 https://walbundrie-p.schools.nsw.gov.au/ 6 March 2020 E: [email protected] Upcoming Events SRPSSA Swimming Carnival Congratulations to our students who competed at the SRPSSA Swimming Friday 6 March Carnival on Friday 21 February. You are all to be commended for your Athletics Clinic - Session 1 sportsmanship and behaviour. Our relay team (Hannah, Angus, Oscar Wednesday 11 March C and Jai), Eli and Owen were successful in making it on to the RPSSA RPSSA Swimming Carnival Swimming Carnival to be held next Wednesday 11 March. Athletics Clinic - Session 2 P&C News Thursday 19 March Paul Kelly Cup @ Culcairn Our first P&C Meeting for 2020 was held last week. As this was the first meeting for 2020, it was also our Annual General Meeting (AGM). Friday 20 March Congratulations to our 2020 P&C Office Bearers: Athletics Clinic - Session 3 President: Tanya Lieschke Tuesday 24 March Vice President: Tiphanie Boyd Year 5 Transition Session @ Secretary: Sarah Packer Billabong High School Treasurer: Katie Kohlhagen Friday 27 March Walbundrie Athletics Carnival Toss Another Snag on the BBQ A reminder that our next BBQ is scheduled to be held this Sunday 8 March. Monday 30 March A timetable has been included in this newsletter. Thank you to all our Paul Kelly Cup @ Wagga families for generously doating their time to man the BBQ throughout the Athletics Clinic - Session 4 day. Come along and support our P&C by buying a snag or two! Friday 3 April Small Schools Athletics Friday Lunch Orders Carnival @ Alexandra Park From this week we will be trialing the preordering of our lunches on a Thursday afternoon, for Friday. -

The District Encompasses Central Victoria and the Lower Part of Central New South Wales

The District encompasses central Victoria and the lower part of central New South Wales. It extends north to Deniliquin, across to Holbrook, Corryong and south to Melbourne's northern suburbs from Heidelberg to Eltham in the east and Sunbury in the west. Rotary District 9790, Australia consists of 61 Clubs and approximately 1800 members. The Rotary Club of Albury is the oldest in the District, being admitted to Rotary International on 2nd November, 1927. In 1927 the District system was first introduced and Albury was in District 65, the territory being the whole of Australia. Other Clubs of our present District followed; Corowa (July) 1939 and Benalla (November) 1939, Wangaratta 1940, Euroa and Yarrawonga-Mulwala 1946, and Shepparton 1948. In 1949 District 65 became District 28, being Tasmania, part of Victoria east of longitude 144 Degrees and part of New South Wales. Deniliquin came in 1950, Wodonga 1953, Myrtleford, Cobram and Seymour 1954 and Heidelberg and Coburg 1956. In 1957 Districts were renumbered and District 28 became District 280, then came Numurkah 1957, Bright and Finley 1959, Kyabram and Preston 1960, Tatura and Broadmeadows 1962, Albury North and Nathalia 1963, Tallangatta and Mooroopna 1964, followed by Alexandra and Thomastown in 1966, Mansfield and Corryong 1967, Greenborough 1968, Reservoir 1969, Albury West 1970 and Appin Park 1972 (now Appin Park Wangaratta). On July 1, 1972 District 280 was divided into two, and the above Clubs became the new District 279. Since then the following Clubs have been admitted to Rotary International: Kilmore/Broadford (1972) (now Southern Mitchell); Sunbury, Eltham, Beechworth and Heidelberg North (1973) (now Rosanna); Shepparton South and Belvoir-Wodonga (1974); Fawkner (1975); Pascoe Vale (1976); Strathmore-Gladstone Park (1977) (now Strathmore), Albury Hume and Healesville (1977); Shepparton Central (1983); Wodonga West (1984); Tocumwal, Lavington, Craigieburn, Holbrook and Mount Beauty (1985); Jerilderie, Yea and Bellbridge Lake Hume (1986); Rutherglen, Bundoora and Nagambie (1987). -

New South Wales Victoria

!( Ardlethan Road R Cr Canola Way edbank eek k WANTIOOL ree !( B C y undi dra a dg in hw ° er Lake Street K ig ! ry H Bethungra C Junee-Illabo re !B M e ILLABO u k r r ee Jun Olympic Highway Underpass track slew umb idg R ee Roa iver d pic") Wade Street bridge modification ym Ol ILLABO O ld H! Man C COOLAMON Junee Station track slew re H! e !( k !H d H and clearance works a Junee H! o R Coolamon Road Kemp Street Bridge Junee Station Footbridge replacement removal G undagai d o o w l l Harefield track slew i R M and clearance works oad St JUNEE urt H! H N ig Wagga Station track slew a hw n a g y HAREFIELD u and clearance works s Wagga Station Footbridge Ro replacement Estella BOMEN ad !( H! k Edmondson Street e k re e C re Bridge replacement e C Bore g H!H!H! Bomen track slew n d !( H o oa H! b R r COOTAMUNDRA n Cassidy Footbridge eplacement e l Wagga l u !( -GUNDAGAI B rcutt -GUNDAGAI rt Forest Hill Ta a kha Wagga Cree Loc k Uranquinty REGIONAL Road ullie !(H Pearson Street Bridge lling URANQUINTY tCo r t l S ha The Rock track slew rack owering !( n ck Ladysmith o Lo and w Green Street clearance works y ad Ro ad rt o ha R M ck ou Lo n Urana ta !( Uranquinty track slew ins H! K and clearance works y e High The Rock a w m a y THE ROCK k b o a o r C r b e l o e k H k e e r Ye C rong C re WAGGA n d e WAGGA k e a v o a Y U R ra H! WAGGA n LOCKHART n e g Yerong Creek YERONG v e a lin Y e track slew CREEK C ree k New South Wales Henty track slew T and clearance works u m b g a ru n m o H!!( w b y Henty a K - g n o l w HENTY o W H a g Ro ad g -

Health Needs Assessment 2017

Health Needs Assessment 2017 Databook KBC Australia P a g e | 1 LIST OF ACRONYMS Acronyms ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics ACPR Aged Care Planning Regions ACT Australian Capital Territory ADHD Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder AEDC Australian Early Development Census AHPRA Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency AIHW Australian Institute of Health and Welfare AMS Aboriginal Medical Service AOD Alcohol and Other Drugs ARIA Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia ASGC Australian Standard Geographical Classification ASGC – RA Australian Standard Geographical Classification – Remoteness Area ATAPS Access to Allied Psychological Services ATSI Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders AUS Australia CAMHS Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services CAODS Calvary Alcohol and Other Drug Services CKD Chronic Kidney Disease CL Consultation Liaison COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease DRGs Diagnostic related group DOH Department of Health ED Emergency Department EN Enrolled Nurse KBC Australia P a g e | 2 ENT Ears/Nose/Throat FACS Family and Community Services FTE Full Time Employee GAMS Griffith Aboriginal Medical Service GP General Practitioner HACC Home and Community Care HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus HNA Health Needs Assessment IARE Indigenous Area IRSEO Indigenous Relative Socioeconomic Outcomes IRSD Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage LGA Local Government Area LHAC Local Health Advisory Committee MBS Medical Benefits Schedule MH Mental Health MHDA Mental Health Drug and Alcohol MHECS Mental Health Emergency -

Culcairn to Corowa Rail Trail in Close Proximity to the Regional Centres of Albury-Wodonga and Wagga Wagga

Culcairn to Corowa Rail Trail With easy accessibility by road or rail the Culcairn to Corowa Rail Trail in close proximity to the regional centres of Albury-Wodonga and Wagga Wagga. It is in a unique position being the only cross border Rail Trail in Australia It will connect with the well established and popular Murray to Mountains Rail Trail in Wahgunyah, Victoria which is in the Rutherglen wine region. This 73km stretch of trail will take users on a tranquil journey showcasing the areas rich farming heritage with gently rolling hills of lush farming countryside. Ending on the banks of the mighty Murray River and home of Australian Federation in Corowa. Services: Culcairn is serviced by the XPT Train service that runs from Sydney to Melbourne offering ease of access for Rail Trail Users. Accommodation, eateries and grocery outlets are available at both Culcairn and Corowa and meals are available at towns along the route. What will the Rail Trail Offer the Communities Along Its’ path?? Boost existing businesses and offer potential for new business A safe place for locals and tourists alike to ride/ walk with minimal traffic interaction. Encourage residents to get out and active. What is there to see along the trail?? See the historic Railway Museum at Culcairn located in the old station masters home Stop in at Walla and see the beautiful Zion Lutheran Church building built by the German families who travelled to the area in 1868 in a Wagon Train. A memorial to these pioneers is located close to the church. Then head to Morgans look out where infamous bushranger “Mad” Dan Morgan hid from police in the 1860’s.