Febrile Seizures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Labs 5. Radiologic Studies 6. General Management 7. Status Epilepticus Pathway 8. Pharmacologic Management 9. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 10. Inpatient Status Admission Criteria a. Admission Pathway 11. Outcome Measures 12. References Last updated: July 7, 2019 Owners: Danielle Hirsch, MD, Emergency Medicine; Jennifer Avallone, DO, Neurology This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 2 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Rationale This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH neurologists/epileptologists, emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, hospitalists, intensivists, nurses, and pharmacists to standardize the management of children treated for status epilepticus. The following clinical issues are addressed: ● When to evaluate for status epilepticus ● When to consider admission for further evaluation and treatment of status epilepticus ● When to consult Neurology, Hospitalists, or Critical Care Team for further management of status epilepticus ● When to obtain further neuroimaging for status epilepticus ● What ongoing therapy patients should receive for status epilepticus Background: Status epilepticus (SE) is the most common neurological emergency in children1 and has the potential to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Incidence among children ranges from 17 to 23 per 100,000 annually.2 Prevalence is highest in pediatric patients from zero to four years of age.3 Ng3 acknowledges the most current definition of SE as a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more distinct seizures without regaining awareness in between. -

Non-Epileptic Seizures a Short Guide for Patients and Families

Non-epileptic seizures a short guide for patients and families Department of Neurology Information for patients Royal Hallamshire Hospital What are non-epileptic seizures? In a seizure people lose control of their body, often causing shaking or other movements of arms and legs, blacking out, or both. Seizures can happen for different reasons. During epileptic seizures, the brain produces electrical impulses, which stop it from working normally. Non-epileptic seizures look a little like epileptic seizures, but are not caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Non-epileptic seizures happen because of problems with handling thoughts, memories, emotions or sensations in the brain. Such problems are sometimes related to stress. However, they can also occur in people who seem calm and relaxed. Often people do not understand why they have developed non-epileptic seizures. Are non-epileptic seizures rare? For every 100,000 people, between 15 and 30 have non- epileptic seizures. Nearly half of all people brought in to hospital with suspected serious epilepsy turn out to have non- epileptic seizures instead. One of the reasons why you may not have heard of non- epileptic seizures is that there are several other names for the same problem. Non-epileptic seizures are also known as pseudoseizures, psychogenic, dissociative or functional seizures. Sometimes people who have non-epileptic seizures are told that they suffer from non-epileptic attack disorder (NEAD). How can I be sure that this is the right diagnosis? Non-epileptic seizures often look like epileptic seizures to friends, family members and even doctors. Like epilepsy, non- epileptic seizures can cause injuries and loss of control over bladder function. -

An Atypical Presentation of Epilepsy; What a Headache! J Neurol Transl Neurosci 5(1): 1078

Central Journal of Neurology & Translational Neuroscience Bringing Excellence in Open Access Case Report Corresponding author Sarah Seyffert, Trinity School of Medicine, 505 Tadmore court Schaumburg, Illinois 60194, USA, Tel: 847-217-4262; An Atypical Presentation of Email: Submitted: 13 April 2017 Epilepsy; What a Headache! Accepted: 07 June 2017 Published: 09 June 2017 Sarah Seyffert* and Wade Kvatum ISSN: 2333-7087 Trinity School of Medicine, USA Copyright © 2017 Seyffert et al. Abstract OPEN ACCESS The relationship between headache and seizure is a poorly understood and controversial topic; however, the literature has recently suggested that the two conditions may be related. Keywords The interplay between these conditions seems to be even more complex in a group of • Epilepsy patients with epilepsy related headaches. It has been proposed that the association could • Headache be classified into preictal, ictal, postictal, or interictal headaches. Here we present a case • Ictal epileptic headache report of a 62 year old male who presented with a chief complaint of new onset severe headache and subsequently underwent multiple diagnostic testing modalities before he was finally diagnosed and treated for epilepsy, which lead to the resolution of his headache. We conclude with a short discussion of how to subcategorize seizure related headaches based on their temporal relationship and why they can pose such a difficult diagnostic challenge. ABBREVIATIONS afebrile with a normal CBC and CMP. On arrival to the hospital he underwent a non-contrast head CT scan; however, no evidence of EEG: Electroencephalogram; CBC: Complete Blood Count; acute intracranial abnormality was seen. Additionally, a lumbar CMP: Complete Metabolic Panel; CT scan: Computerized puncture was performed which was negative for xanthochromia Tomography Scan; CTA: Computed Tomographic Angiography; and showed a protein count of 27, glucose 230, and 2 white MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging blood cells. -

Seizure Triggers

SEIZURE TRIGGERS M A R I A R AQUEL LOPEZ. M.D M I A M I V H A DEFINITION OF SEIZURE VS. EPILEPSY • Epileptic seizure: Is a transient symptom of abnormal excessive electric activity of the brain. EPILEPSY • More than one epileptic seizure. TYPE OF SEIZURES ETIOLOGY • Epilepsy is a heterogeneous condition with varying etiologies including: 1. Genetic 2. Infectious 3. Trauma 4. Vascular 5. Neoplasm 6. Toxic exposures TRIGGERS FOR EPILEPTIC SEIZURES • What is a seizure trigger? It is a factor that can cause a seizure in a person who either has epilepsy or does not. • Factors that lead into a seizure are complex and it is not possible to determine the trigger in each patient. TRIGGERS A. Most common ones Stress Missing taking the medication THE MOST OFTEN REPORTED BY PATIENTS • Sleep deprivation and tiredness • Fever OTHER COMMON CAUSES . Infection . Fasting leading into hypoglycemia. Caffeine: particularly if it interrupts normal sleep patterns. Other medications like hormonal replacement, pain killers or antibiotics. OTHER TRIGGERS External precipitants • Alcohol consumption or withdrawal. *Specific triggers that are related to Reflex epilepsy Bathing Eating Reading OTHER TRIGGERS • Flashing light: especially with patients with idiopathic generalized seizure disorder STRESS . Stress is the most common patient –perceived seizure precipitant, studies of life events suggest that stressful experiences trigger seizures in certain individuals. Animals epilepsy models provide more convincing evidence that exposure to exogenous and endogenous stress mediators has been found to increase epileptic activity in the brain, especially after repeating exposure. SOLUTION ABOUT STRESS • Intervention of copying with stress STRESS MANAGEMENT • Include trying to get in a place of peace utilizing multiple techniques: • Regular exercise • Yoga and medication • Therapy or psychological support with a provider. -

Seizure, New Onset

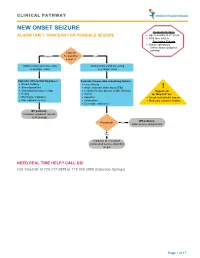

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

The Genetic Relationship Between Paroxysmal Movement Disorders and Epilepsy

Review article pISSN 2635-909X • eISSN 2635-9103 Ann Child Neurol 2020;28(3):76-87 https://doi.org/10.26815/acn.2020.00073 The Genetic Relationship between Paroxysmal Movement Disorders and Epilepsy Hyunji Ahn, MD, Tae-Sung Ko, MD Department of Pediatrics, Asan Medical Center Children’s Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Received: May 1, 2020 Revised: May 12, 2020 Seizures and movement disorders both involve abnormal movements and are often difficult to Accepted: May 24, 2020 distinguish due to their overlapping phenomenology and possible etiological commonalities. Par- oxysmal movement disorders, which include three paroxysmal dyskinesia syndromes (paroxysmal Corresponding author: kinesigenic dyskinesia, paroxysmal non-kinesigenic dyskinesia, paroxysmal exercise-induced dys- Tae-Sung Ko, MD kinesia), hemiplegic migraine, and episodic ataxia, are important examples of conditions where Department of Pediatrics, Asan movement disorders and seizures overlap. Recently, many articles describing genes associated Medical Center Children’s Hospital, University of Ulsan College of with paroxysmal movement disorders and epilepsy have been published, providing much infor- Medicine, 88 Olympic-ro 43-gil, mation about their molecular pathology. In this review, we summarize the main genetic disorders Songpa-gu, Seoul 05505, Korea that results in co-occurrence of epilepsy and paroxysmal movement disorders, with a presenta- Tel: +82-2-3010-3390 tion of their genetic characteristics, suspected pathogenic mechanisms, and detailed descriptions Fax: +82-2-473-3725 of paroxysmal movement disorders and seizure types. E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Dyskinesias; Movement disorders; Seizures; Epilepsy Introduction ies, and paroxysmal dyskinesias [3,4]. Paroxysmal dyskinesias are an important disease paradigm asso- Movement disorders often arise from the basal ganglia nuclei or ciated with overlapping movement disorders and seizures [5]. -

The Frequency of Seizures with Roseola. the Study Corroborates the Suggestion That Seizures with Roseola, HHV-6, and Fever Are Not Always Simple in Type

the frequency of seizures with roseola. The study corroborates the suggestion that seizures with roseola, HHV-6, and fever are not always simple in type. They are frequently prolonged, recurrent, and complex, and sometimes a manifestation of encephalitis or encephalopathy. (Progress in Pediatric Neurology II. Millichap JG, Ed, PNB Publ, 1994, pp 410, 415). These findings further weaken the hypothesis of the so-called simple febrile seizure as a distinct disease entity. For abstracts from the 16th annual conference on febrile convulsions held in Tokyo, Dec 18, 1993, see Fukuyama Y. Brain Dev July/Aug 1994;16:339-346. Papers included neurochemical aspects, EEG studies, and clinical, epidemiological, and treatment reports. The reputed safety and effectiveness of intermittent oral diazepam (0.4 mg/kg, 3 doses) at times of fever for prevention of recurrence of febrile seizures was supported in 23 children treated at Shimane Medical University and Central Hospital, Japan. GLUTAMATE IN PYRIDOXINE-DEPENDENT EPILEPSY Cerebrospinal fluid levels of glutamate, g-aminobutyric acid, and pyridoxal-5-phosphate examined in a patient with pyridoxine dependency while on and off vitamin B6 treatment are reported from Universitat Munchen, and Universitats-Nervenklinik, Wurzburg, Germany. Seizures began at age 3 weeks. Despite phenobarbital, status epilepticus occurred at 3 months and was followed by infantile spasms and hypsarrhythmia. The addition of ACTH and vitamin B6 controlled the seizures and the EEG became normal. Seizures recurred on each of several occasions when vitamin B6 was withdrawn. CSF glutamate was elevated 200-fold, whereas GABA and PLP were normal. After vitamin B6 (5 mg/kg BW/day) was reintroduced, seizures stopped and the EEG was normal, but CSF glutamate was still elevated 10 fold. -

Epilepsy After Stroke

Stroke Helpline: 0303 3033 100 Website: stroke.org.uk Epilepsy after stroke In the first few weeks after a stroke some people have a seizure, and a small number go on to develop epilepsy – a tendency to have repeated seizures. These can usually be completely controlled with treatment. This factsheet explains what epilepsy is, the different types of seizures, and how epilepsy is diagnosed and treated. It also includes advice about coping with a seizure, and a glossary. Epilepsy is a tendency to have repeated What causes seizures? seizures – sometimes called ‘fits’ or ‘attacks’. It affects just under one per cent Cells in the brain communicate with one of people in the UK. Stroke is one of many another and with our muscles by passing conditions that can lead to epilepsy. electrical signals along nerve fibres. If you have epilepsy this electrical activity can Around five per cent of people who have a become disordered. A sudden abnormal stroke will have a seizure within the following burst of electrical activity in the brain can few weeks. These are known as acute or lead to a seizure. onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke. You are more likely There are over 40 different types of seizures to have one if you have had a severe stroke, ranging from tingling sensations or ‘going a stroke caused by bleeding in the brain (a blank’ for a few seconds, to shaking and haemorrhagic stroke), or a stroke involving losing consciousness. the part of the brain called the cerebral cortex. If you have an onset seizure, it This can mean that epilepsy is sometimes does not necessarily mean you have or will confused with other conditions, including develop epilepsy. -

Febrile Seizures: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Long-Term Management of the Child with Simple Febrile Seizures

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Febrile Seizures: Clinical Practice Guideline for the Long-term Management of the Child With Simple Febrile Seizures Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management, Subcommittee on Febrile Seizures ABSTRACT Febrile seizures are the most common seizure disorder in childhood, affecting 2% to 5% of children between the ages of 6 and 60 months. Simple febrile seizures are www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/ peds.2008-0939 defined as brief (Ͻ15-minute) generalized seizures that occur once during a 24-hour period in a febrile child who does not have an intracranial infection, doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0939 metabolic disturbance, or history of afebrile seizures. This guideline (a revision of All clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics automatically expire the 1999 American Academy of Pediatrics practice parameter [now termed clinical 5 years after publication unless reaffirmed, practice guideline] “The Long-term Treatment of the Child With Simple Febrile revised, or retired at or before that time. Seizures”) addresses the risks and benefits of both continuous and intermittent The guidance in this report does not anticonvulsant therapy as well as the use of antipyretics in children with simple indicate an exclusive course of treatment febrile seizures. It is designed to assist pediatricians by providing an analytic or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual framework for decisions regarding possible therapeutic interventions in this pa- circumstances, may be appropriate. tient population. It is not intended to replace clinical judgment or to establish a Key Word protocol for all patients with this disorder. -

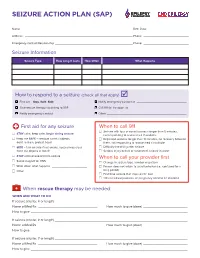

Seizure Action Plan (Sap)

SEIZURE ACTION PLAN (SAP) Name: ——————————————————————————————————————————————————— Birth Date: ——————————————————— Address: —————————————————————————————————————————————————— Phone: ————————————————————— Emergency Contact/Relationship ———————————————————————————————————— Phone: ————————————————————— Seizure Information Seizure Type How Long It Lasts How Often What Happens How to respond to a seizure (check all that apply) F First aid – Stay. Safe. Side. F Notify emergency contact at ______________________________ F Give rescue therapy according to SAP F Call 911 for transport to __________________________________________ F Notify emergency contact F Other ________________________________________________ First aid for any seizure When to call 911 F Seizure with loss of consciousness longer than 5 minutes, F STAY calm, keep calm, begin timing seizure not responding to rescue med if available F Keep me SAFE – remove harmful objects, F Repeated seizures longer than 10 minutes, no recovery between don’t restrain, protect head them, not responding to rescue med if available F SIDE – turn on side if not awake, keep airway clear, F Difficulty breathing after seizure don’t put objects in mouth F Serious injury occurs or suspected, seizure in water F STAY until recovered from seizure When to call your provider first F Swipe magnet for VNS F Change in seizure type, number or pattern F Write down what happens _____________________ F Person does not return to usual behavior (i.e., confused for a F Other _____________________________________ long -

Chloride Channelopathies Rosa Planells-Cases, Thomas J

Chloride channelopathies Rosa Planells-Cases, Thomas J. Jentsch To cite this version: Rosa Planells-Cases, Thomas J. Jentsch. Chloride channelopathies. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease, Elsevier, 2009, 1792 (3), pp.173. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.02.002. hal- 00501604 HAL Id: hal-00501604 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00501604 Submitted on 12 Jul 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ÔØ ÅÒÙ×Ö ÔØ Chloride channelopathies Rosa Planells-Cases, Thomas J. Jentsch PII: S0925-4439(09)00036-2 DOI: doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.02.002 Reference: BBADIS 62931 To appear in: BBA - Molecular Basis of Disease Received date: 23 December 2008 Revised date: 1 February 2009 Accepted date: 3 February 2009 Please cite this article as: Rosa Planells-Cases, Thomas J. Jentsch, Chloride chan- nelopathies, BBA - Molecular Basis of Disease (2009), doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.02.002 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. -

Psychotic Disorder Due to Lafora Disease: a Case Report

2015 iMedPub Journals Clinical Psychiatry http://www.imedpub.com Vol. 1 No. 1:2 Psychotic Disorder Due to Lafora Şafak Taktak1 , 2 Disease: A Case Report Mustafa Karakuş 1 Psychiatry Department, Ahi Evran University Education and Research Hospital, Turkey 2 Forensic Medicine and Emergency Medicine Department, Yenimahalle Abstract Education and Research Hospital, Turkey Lafora disease is a type of progressive myoclonic epilepsy with poor prognosis, characterized by myoclonus, seizures, cerebellar ataxia and mental disorder. Lafora disease frequently develops at 10-18 years of age and tranmission is autosomal recessive. The first symptoms are usually Corresponding author: Şafak Taktak myoclonic, tonic-clonic, atonic or absence seizures. Epilepsy in children and adolescents with depression, anxiety disorders, attention deficit Psychiatry Department, Ahi Evran hyperactivity disorder can be seen relatively frequently. More rarely, these University Education and Research people can be seen in psychotic disorders. In this paper, we aimed to draw Hospital, Turkey attention to diagnosis of fatal, resistance to treatment with serious suicide attempt and diagnosis of Lafora developing psychotic symptoms in children. [email protected] Tel: 05054037967 Introduction from effective treatment and resulting in death was reported , as Epilepsy in childhood, with prevalence 0,5-1 %, are among the a case report [1-11]. most common neurological diagnosis. Progressive myoclonic constitutes less than 1% of all epilepsies, while Lafora disease Case constitutes 10% of all epilepsies. Lafora disease is a type of progressive myoclonic epilepsy with poor prognosis, characterized The index case, a 12-year-old girl, who had a family history of by myoclonus, seizures, cerebellar ataxia and mental disorder.