Non-Epileptic Seizures a Short Guide for Patients and Families

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Labs 5. Radiologic Studies 6. General Management 7. Status Epilepticus Pathway 8. Pharmacologic Management 9. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 10. Inpatient Status Admission Criteria a. Admission Pathway 11. Outcome Measures 12. References Last updated: July 7, 2019 Owners: Danielle Hirsch, MD, Emergency Medicine; Jennifer Avallone, DO, Neurology This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 2 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Rationale This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH neurologists/epileptologists, emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, hospitalists, intensivists, nurses, and pharmacists to standardize the management of children treated for status epilepticus. The following clinical issues are addressed: ● When to evaluate for status epilepticus ● When to consider admission for further evaluation and treatment of status epilepticus ● When to consult Neurology, Hospitalists, or Critical Care Team for further management of status epilepticus ● When to obtain further neuroimaging for status epilepticus ● What ongoing therapy patients should receive for status epilepticus Background: Status epilepticus (SE) is the most common neurological emergency in children1 and has the potential to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Incidence among children ranges from 17 to 23 per 100,000 annually.2 Prevalence is highest in pediatric patients from zero to four years of age.3 Ng3 acknowledges the most current definition of SE as a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more distinct seizures without regaining awareness in between. -

An Atypical Presentation of Epilepsy; What a Headache! J Neurol Transl Neurosci 5(1): 1078

Central Journal of Neurology & Translational Neuroscience Bringing Excellence in Open Access Case Report Corresponding author Sarah Seyffert, Trinity School of Medicine, 505 Tadmore court Schaumburg, Illinois 60194, USA, Tel: 847-217-4262; An Atypical Presentation of Email: Submitted: 13 April 2017 Epilepsy; What a Headache! Accepted: 07 June 2017 Published: 09 June 2017 Sarah Seyffert* and Wade Kvatum ISSN: 2333-7087 Trinity School of Medicine, USA Copyright © 2017 Seyffert et al. Abstract OPEN ACCESS The relationship between headache and seizure is a poorly understood and controversial topic; however, the literature has recently suggested that the two conditions may be related. Keywords The interplay between these conditions seems to be even more complex in a group of • Epilepsy patients with epilepsy related headaches. It has been proposed that the association could • Headache be classified into preictal, ictal, postictal, or interictal headaches. Here we present a case • Ictal epileptic headache report of a 62 year old male who presented with a chief complaint of new onset severe headache and subsequently underwent multiple diagnostic testing modalities before he was finally diagnosed and treated for epilepsy, which lead to the resolution of his headache. We conclude with a short discussion of how to subcategorize seizure related headaches based on their temporal relationship and why they can pose such a difficult diagnostic challenge. ABBREVIATIONS afebrile with a normal CBC and CMP. On arrival to the hospital he underwent a non-contrast head CT scan; however, no evidence of EEG: Electroencephalogram; CBC: Complete Blood Count; acute intracranial abnormality was seen. Additionally, a lumbar CMP: Complete Metabolic Panel; CT scan: Computerized puncture was performed which was negative for xanthochromia Tomography Scan; CTA: Computed Tomographic Angiography; and showed a protein count of 27, glucose 230, and 2 white MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging blood cells. -

Seizure Triggers

SEIZURE TRIGGERS M A R I A R AQUEL LOPEZ. M.D M I A M I V H A DEFINITION OF SEIZURE VS. EPILEPSY • Epileptic seizure: Is a transient symptom of abnormal excessive electric activity of the brain. EPILEPSY • More than one epileptic seizure. TYPE OF SEIZURES ETIOLOGY • Epilepsy is a heterogeneous condition with varying etiologies including: 1. Genetic 2. Infectious 3. Trauma 4. Vascular 5. Neoplasm 6. Toxic exposures TRIGGERS FOR EPILEPTIC SEIZURES • What is a seizure trigger? It is a factor that can cause a seizure in a person who either has epilepsy or does not. • Factors that lead into a seizure are complex and it is not possible to determine the trigger in each patient. TRIGGERS A. Most common ones Stress Missing taking the medication THE MOST OFTEN REPORTED BY PATIENTS • Sleep deprivation and tiredness • Fever OTHER COMMON CAUSES . Infection . Fasting leading into hypoglycemia. Caffeine: particularly if it interrupts normal sleep patterns. Other medications like hormonal replacement, pain killers or antibiotics. OTHER TRIGGERS External precipitants • Alcohol consumption or withdrawal. *Specific triggers that are related to Reflex epilepsy Bathing Eating Reading OTHER TRIGGERS • Flashing light: especially with patients with idiopathic generalized seizure disorder STRESS . Stress is the most common patient –perceived seizure precipitant, studies of life events suggest that stressful experiences trigger seizures in certain individuals. Animals epilepsy models provide more convincing evidence that exposure to exogenous and endogenous stress mediators has been found to increase epileptic activity in the brain, especially after repeating exposure. SOLUTION ABOUT STRESS • Intervention of copying with stress STRESS MANAGEMENT • Include trying to get in a place of peace utilizing multiple techniques: • Regular exercise • Yoga and medication • Therapy or psychological support with a provider. -

Seizure, New Onset

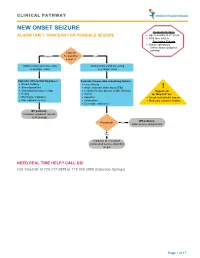

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

Epilepsy After Stroke

Stroke Helpline: 0303 3033 100 Website: stroke.org.uk Epilepsy after stroke In the first few weeks after a stroke some people have a seizure, and a small number go on to develop epilepsy – a tendency to have repeated seizures. These can usually be completely controlled with treatment. This factsheet explains what epilepsy is, the different types of seizures, and how epilepsy is diagnosed and treated. It also includes advice about coping with a seizure, and a glossary. Epilepsy is a tendency to have repeated What causes seizures? seizures – sometimes called ‘fits’ or ‘attacks’. It affects just under one per cent Cells in the brain communicate with one of people in the UK. Stroke is one of many another and with our muscles by passing conditions that can lead to epilepsy. electrical signals along nerve fibres. If you have epilepsy this electrical activity can Around five per cent of people who have a become disordered. A sudden abnormal stroke will have a seizure within the following burst of electrical activity in the brain can few weeks. These are known as acute or lead to a seizure. onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke. You are more likely There are over 40 different types of seizures to have one if you have had a severe stroke, ranging from tingling sensations or ‘going a stroke caused by bleeding in the brain (a blank’ for a few seconds, to shaking and haemorrhagic stroke), or a stroke involving losing consciousness. the part of the brain called the cerebral cortex. If you have an onset seizure, it This can mean that epilepsy is sometimes does not necessarily mean you have or will confused with other conditions, including develop epilepsy. -

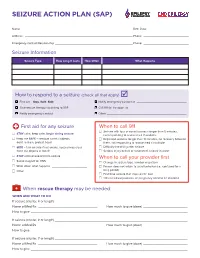

Seizure Action Plan (Sap)

SEIZURE ACTION PLAN (SAP) Name: ——————————————————————————————————————————————————— Birth Date: ——————————————————— Address: —————————————————————————————————————————————————— Phone: ————————————————————— Emergency Contact/Relationship ———————————————————————————————————— Phone: ————————————————————— Seizure Information Seizure Type How Long It Lasts How Often What Happens How to respond to a seizure (check all that apply) F First aid – Stay. Safe. Side. F Notify emergency contact at ______________________________ F Give rescue therapy according to SAP F Call 911 for transport to __________________________________________ F Notify emergency contact F Other ________________________________________________ First aid for any seizure When to call 911 F Seizure with loss of consciousness longer than 5 minutes, F STAY calm, keep calm, begin timing seizure not responding to rescue med if available F Keep me SAFE – remove harmful objects, F Repeated seizures longer than 10 minutes, no recovery between don’t restrain, protect head them, not responding to rescue med if available F SIDE – turn on side if not awake, keep airway clear, F Difficulty breathing after seizure don’t put objects in mouth F Serious injury occurs or suspected, seizure in water F STAY until recovered from seizure When to call your provider first F Swipe magnet for VNS F Change in seizure type, number or pattern F Write down what happens _____________________ F Person does not return to usual behavior (i.e., confused for a F Other _____________________________________ long -

Psychotic Disorder Due to Lafora Disease: a Case Report

2015 iMedPub Journals Clinical Psychiatry http://www.imedpub.com Vol. 1 No. 1:2 Psychotic Disorder Due to Lafora Şafak Taktak1 , 2 Disease: A Case Report Mustafa Karakuş 1 Psychiatry Department, Ahi Evran University Education and Research Hospital, Turkey 2 Forensic Medicine and Emergency Medicine Department, Yenimahalle Abstract Education and Research Hospital, Turkey Lafora disease is a type of progressive myoclonic epilepsy with poor prognosis, characterized by myoclonus, seizures, cerebellar ataxia and mental disorder. Lafora disease frequently develops at 10-18 years of age and tranmission is autosomal recessive. The first symptoms are usually Corresponding author: Şafak Taktak myoclonic, tonic-clonic, atonic or absence seizures. Epilepsy in children and adolescents with depression, anxiety disorders, attention deficit Psychiatry Department, Ahi Evran hyperactivity disorder can be seen relatively frequently. More rarely, these University Education and Research people can be seen in psychotic disorders. In this paper, we aimed to draw Hospital, Turkey attention to diagnosis of fatal, resistance to treatment with serious suicide attempt and diagnosis of Lafora developing psychotic symptoms in children. [email protected] Tel: 05054037967 Introduction from effective treatment and resulting in death was reported , as Epilepsy in childhood, with prevalence 0,5-1 %, are among the a case report [1-11]. most common neurological diagnosis. Progressive myoclonic constitutes less than 1% of all epilepsies, while Lafora disease Case constitutes 10% of all epilepsies. Lafora disease is a type of progressive myoclonic epilepsy with poor prognosis, characterized The index case, a 12-year-old girl, who had a family history of by myoclonus, seizures, cerebellar ataxia and mental disorder. -

Episode 133 Emergency Management of Status Epilepticus

• ABCDEFG (ABC’s and Don’t Ever Forget the Glucose) – capillary glucose • Airway: position in lateral decubitus (when/if possible to minimize aspiration risk) or head up with ongoing suction, nasal trumpets, suction Episode 133 Emergency Management of Status • Attempt IV access and send for VBG, glucose, electrolytes Epilepticus (Na, Ca, Mg), tox screen, BhCG, CK, Cr, lactate • Consider crystalloid bolus, draw up push dose pressor for prevention/management of potential hypotension With Drs. Paul Koblic & Aylin Reid • IV Lorazepam or IM Midazolam Prepared by Winny Li & Lorraine Lau, Dec 2019 • If no response to first dose of IV benzodiazepine, start phenytoin/fosphenytoin (avoid in tox), valproate or Status Epilepticus Definition levetiracetam • Prepare to intubate via RSI with propofol or “ketofol” and • Continuous seizure lasting > 5 minutes OR rocuronium (if Sugammadex is available or seizure >20- • 2 or more seizures within a 5-minute period without 25 mins) or succinylcholine return to neurological baseline in between • Consider immediate life-threats that require immediate treatment with specific antidotes: Most seizures resolve spontaneously in 1-3 minutes. However, o Vital sign extremes: hypoxemia (O2), hypertensive by the time the seizure is identified, physician is notified and encephalopathy (labetolol, nitroprusside) and attends to the patient, IV access is obtained, drugs are drawn up severe hyperthermia (cooling) and given, most actively seizing patients who have not already o Metabolic: hypoglycemia (glucose), hyponatremia stopped seizing will be in status epilepticus. (hypertonic saline), hypomagnesemia (Mg), hypocalcemia (Ca) Initial ED management of Status Epilepticus o Toxicologic: anticholinergics (HCO3), isoniazid (pyridoxine), lipophilic drug overdose (lipid emulsion) etc. • Call for help as many steps of the management will occur o Eclampsia: typically, > 20 weeks of pregnancy and in parallel. -

Post-Epileptic Headache and Migraine

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.50.9.1148 on 1 September 1987. Downloaded from Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1987;50:1148-1152 Post-epileptic headache and migraine F SCHON, J N BLAU From the National Hospitalsfor Nervous Diseases, Maida Vale Hospital, London, UK SUMMARY One hundred epileptic patients were questioned about their headaches. Post-ictal head- aches occurred in 51 of these patients and most commonly lasted 6-72 hours. Major seizures were more often associated with post-epileptic headaches than minor attacks. Nine patients in this series of 100 also had migraine: in eight of these nine a typical, albeit a mild, migraine attack was provoked by fits. The post-ictal headache in the 40 epileptics who did not have migraine was accompanied by vomiting in 11 cases, photophobia in 14 cases and vomiting with photophobia in 4 cases. Further- more, post-epileptic headache was accentuated by coughing, bending and sudden head movements and relieved by sleep. It is, therefore, clear that seizures provoke a syndrome similar to the headache phase of migraine in 50% of epileptics. It is proposed that post-epileptic headache arises intra- cranially and is related to the vasodilatation known to follow seizures. The relationship of post- epileptic headache to migraine is discussed in the light of current ideas on migraine pathogenesis, in particular the vasodilation which accompanies Leao's spreading cortical depression. Protected by copyright. Little is known about post-epileptic headaches, al- including nausea and vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, though their occurrence is accepted by patients and and visual disturbances were also noted. -

Management of Status Epilepticus JOSEPH I

Management of Status Epilepticus JOSEPH I. SIRVEN, M.D., Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona ELIZABETH WATERHOUSE, M.D., Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Richmond, Virginia Status epilepticus is an increasingly recognized public health problem in the United States. Status epilepticus is associated with a high mortality rate that is largely contingent on the duration of the condition before initial treatment, the etiology of the condition, and the age of the patient. Treatment is evolving as new medications become available. Three new preparations—fos- phenytoin, rectal diazepam, and parenteral valproate—have implications for the management of status epilepticus. However, randomized controlled trials show that benzodiazepines (in particu- lar, diazepam and lorazepam) should be the initial drug therapy in patients with status epilepti- cus. Despite the paucity of clinical trials comparing medication regimens for acute seizures, there is broad consensus that immediate diagnosis and treatment are necessary to reduce the morbid- ity and mortality of this condition. Moreover, investigators have reported that status epilepticus often is not considered in patients with altered consciousness in the intensive care setting. In patients with persistent alteration of consciousness for which there is no clear etiology, physicians should be more quickly prepared to obtain electroencephalography to identify status epilepticus. Physicians should rely on a standardized protocol for management of status epilepticus to improve care for this neurologic emergency. (Am Fam Physician 2003;68:469-76. Copyright© 2003 American Academy of Family Physicians.) tatus epilepticus is an under-recog- cus. Practically speaking, any person who nized health problem associated exhibits persistent seizure activity or who does with substantial morbidity and not regain consciousness for five minutes or mortality. -

Epileptic Seizures in Neurodegenerative Dementia Syndromes

2010 iMedPub Journals JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGY AND NEUROSCIENCE Vol.1 No. 1:3 doi: 10:3823/302 Epileptic seizures in neurodegenerative dementia syndromes AJ Larner Consultant Neurologist. Cognitive Function Clinic, Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Liverpool, United Kingdom Correspondence: AJ Larner, Cognitive Function Clinic, Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Lower Lane, Fazakerley, Liverpool, UK Tel: (44) 151 529 5727 FAX: (44) 151 529 8552 e-mail: [email protected] Summary Epileptic seizures may be a feature of some neurodegenerative dementia syndromes. There is an increased incidence of seizures in Alzheimer’s disease compared to age-matched controls. Seizures also occur in prion disorders and some frontotemporal lobar degenera- tion syndromes, whereas parkinsonian dementia disorders seem relatively seizure free. Seizure pathogenesis in these conditions is uncer- tain, but may relate to neocortical and hippocampal hyperexcitability and synchronised activity, possibly as a consequence of dysfunctio- nal protein metabolism, neuronal structural changes, and concurrent cerebrovascular disease. Alzheimer’s disease may be a neuronal network disorder, characterised by both cognitive decline and epileptic activity, in which seizures are an integral part of disease phenotype rather than epiphenomena. Treatment of seizures in dementia syndromes currently remains empirical. Greater understanding of demen- tia pathogenesis may shed light on mechanisms of epileptogenesis and facilitate more rational approaches -

Management of Acute Seizure and Status Epilepticus

Management of acute seizure and status epilepticus Apisit Boongird, MD Division of Neurology Ramathibodi Hospital Sunday August 27, 2560 Topics • Acute repetitive seizure • Status epilepticus Definition of epileptic seizure by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) • An epileptic seizure is a transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms due to abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. Epilepsia, 46(4):470–472, 2005 Acute repetitive seizures (Seizure clusters) Acute repetitive seizures (ARS) • Home • OPD • IPD Acute Repetitive Seizures (ARS) • The practical definition of acute repetitive seizures has not been established. • Acute repetitive seizures is neurologic emergency and a common clinical phenomenon describing an increase in seizures occurring over a specific period of time (ranging from several minutes up to 24 hours). • Acute repetitive seizures may include any type of seizure and may vary in severity, but by definition there is complete recovery in between seizures. Curr Opin Neurol 2015;28(2):143Y150. Management of acute repetitive seizures (ARS) • Stop the seizures • Identify the etiology of acute repetitive seizures • Benzodiazepines remain the mainstay of therapy. • The treatment of ARS includes the usage of extra doses of usual antiepileptic medications and oral benzodiazepines (diazepam or lorazepam) for mild ARS. • A 45 yo presented with first unprovoked seizures a year ago. seizure type 1: left face clonic with preserved awareness seizure duration: 5 minutes treatment: LEV 500-500 + tumor removal • In August 2560, he had ARS for 2 hours. Outpatient acute benzodiazepine therapy • Rectal diazepam is the only currently marketed treatment available for use by nonmedical caregivers in the USA, and buccal midazolam is approved in the European Union.