Seizures and Epilepsy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Labs 5. Radiologic Studies 6. General Management 7. Status Epilepticus Pathway 8. Pharmacologic Management 9. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 10. Inpatient Status Admission Criteria a. Admission Pathway 11. Outcome Measures 12. References Last updated: July 7, 2019 Owners: Danielle Hirsch, MD, Emergency Medicine; Jennifer Avallone, DO, Neurology This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 2 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Status Epilepticus Clinical Pathway Rationale This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH neurologists/epileptologists, emergency physicians, advanced practice providers, hospitalists, intensivists, nurses, and pharmacists to standardize the management of children treated for status epilepticus. The following clinical issues are addressed: ● When to evaluate for status epilepticus ● When to consider admission for further evaluation and treatment of status epilepticus ● When to consult Neurology, Hospitalists, or Critical Care Team for further management of status epilepticus ● When to obtain further neuroimaging for status epilepticus ● What ongoing therapy patients should receive for status epilepticus Background: Status epilepticus (SE) is the most common neurological emergency in children1 and has the potential to cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Incidence among children ranges from 17 to 23 per 100,000 annually.2 Prevalence is highest in pediatric patients from zero to four years of age.3 Ng3 acknowledges the most current definition of SE as a continuous seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more distinct seizures without regaining awareness in between. -

Non-Epileptic Seizures a Short Guide for Patients and Families

Non-epileptic seizures a short guide for patients and families Department of Neurology Information for patients Royal Hallamshire Hospital What are non-epileptic seizures? In a seizure people lose control of their body, often causing shaking or other movements of arms and legs, blacking out, or both. Seizures can happen for different reasons. During epileptic seizures, the brain produces electrical impulses, which stop it from working normally. Non-epileptic seizures look a little like epileptic seizures, but are not caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Non-epileptic seizures happen because of problems with handling thoughts, memories, emotions or sensations in the brain. Such problems are sometimes related to stress. However, they can also occur in people who seem calm and relaxed. Often people do not understand why they have developed non-epileptic seizures. Are non-epileptic seizures rare? For every 100,000 people, between 15 and 30 have non- epileptic seizures. Nearly half of all people brought in to hospital with suspected serious epilepsy turn out to have non- epileptic seizures instead. One of the reasons why you may not have heard of non- epileptic seizures is that there are several other names for the same problem. Non-epileptic seizures are also known as pseudoseizures, psychogenic, dissociative or functional seizures. Sometimes people who have non-epileptic seizures are told that they suffer from non-epileptic attack disorder (NEAD). How can I be sure that this is the right diagnosis? Non-epileptic seizures often look like epileptic seizures to friends, family members and even doctors. Like epilepsy, non- epileptic seizures can cause injuries and loss of control over bladder function. -

An Atypical Presentation of Epilepsy; What a Headache! J Neurol Transl Neurosci 5(1): 1078

Central Journal of Neurology & Translational Neuroscience Bringing Excellence in Open Access Case Report Corresponding author Sarah Seyffert, Trinity School of Medicine, 505 Tadmore court Schaumburg, Illinois 60194, USA, Tel: 847-217-4262; An Atypical Presentation of Email: Submitted: 13 April 2017 Epilepsy; What a Headache! Accepted: 07 June 2017 Published: 09 June 2017 Sarah Seyffert* and Wade Kvatum ISSN: 2333-7087 Trinity School of Medicine, USA Copyright © 2017 Seyffert et al. Abstract OPEN ACCESS The relationship between headache and seizure is a poorly understood and controversial topic; however, the literature has recently suggested that the two conditions may be related. Keywords The interplay between these conditions seems to be even more complex in a group of • Epilepsy patients with epilepsy related headaches. It has been proposed that the association could • Headache be classified into preictal, ictal, postictal, or interictal headaches. Here we present a case • Ictal epileptic headache report of a 62 year old male who presented with a chief complaint of new onset severe headache and subsequently underwent multiple diagnostic testing modalities before he was finally diagnosed and treated for epilepsy, which lead to the resolution of his headache. We conclude with a short discussion of how to subcategorize seizure related headaches based on their temporal relationship and why they can pose such a difficult diagnostic challenge. ABBREVIATIONS afebrile with a normal CBC and CMP. On arrival to the hospital he underwent a non-contrast head CT scan; however, no evidence of EEG: Electroencephalogram; CBC: Complete Blood Count; acute intracranial abnormality was seen. Additionally, a lumbar CMP: Complete Metabolic Panel; CT scan: Computerized puncture was performed which was negative for xanthochromia Tomography Scan; CTA: Computed Tomographic Angiography; and showed a protein count of 27, glucose 230, and 2 white MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging blood cells. -

Seizure Triggers

SEIZURE TRIGGERS M A R I A R AQUEL LOPEZ. M.D M I A M I V H A DEFINITION OF SEIZURE VS. EPILEPSY • Epileptic seizure: Is a transient symptom of abnormal excessive electric activity of the brain. EPILEPSY • More than one epileptic seizure. TYPE OF SEIZURES ETIOLOGY • Epilepsy is a heterogeneous condition with varying etiologies including: 1. Genetic 2. Infectious 3. Trauma 4. Vascular 5. Neoplasm 6. Toxic exposures TRIGGERS FOR EPILEPTIC SEIZURES • What is a seizure trigger? It is a factor that can cause a seizure in a person who either has epilepsy or does not. • Factors that lead into a seizure are complex and it is not possible to determine the trigger in each patient. TRIGGERS A. Most common ones Stress Missing taking the medication THE MOST OFTEN REPORTED BY PATIENTS • Sleep deprivation and tiredness • Fever OTHER COMMON CAUSES . Infection . Fasting leading into hypoglycemia. Caffeine: particularly if it interrupts normal sleep patterns. Other medications like hormonal replacement, pain killers or antibiotics. OTHER TRIGGERS External precipitants • Alcohol consumption or withdrawal. *Specific triggers that are related to Reflex epilepsy Bathing Eating Reading OTHER TRIGGERS • Flashing light: especially with patients with idiopathic generalized seizure disorder STRESS . Stress is the most common patient –perceived seizure precipitant, studies of life events suggest that stressful experiences trigger seizures in certain individuals. Animals epilepsy models provide more convincing evidence that exposure to exogenous and endogenous stress mediators has been found to increase epileptic activity in the brain, especially after repeating exposure. SOLUTION ABOUT STRESS • Intervention of copying with stress STRESS MANAGEMENT • Include trying to get in a place of peace utilizing multiple techniques: • Regular exercise • Yoga and medication • Therapy or psychological support with a provider. -

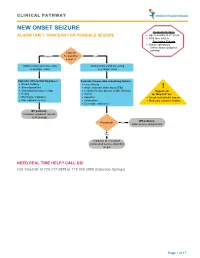

Seizure, New Onset

CLINICAL PATHWAY NEW ONSET SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria ALGORITHM 1. CONCERN FOR POSSIBLE SEIZURE • Age 6 months to 21 years • First-time seizure Exclusion Criteria • Status epilepticus (refer to status epilepticus pathway) Concern Unsure for possible Yes seizure? Obtain history and screening Obtain history and screening neurologic exam neurologic exam Consider differential diagnoses: Evaluate for possible provoking factors: • Breath holding • Fever/illness • Stereotypies/tics • Acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) ! • Vasovagal/syncope/vertigo • Central nervous system (CNS) infection Urgent call • Reflux • Tumor to ‘OneCall’ for: • Electrolyte imbalance • Ingestion • Suspected infantile spasm • Non epileptic seizure • Intoxication • Medically complex children • Electrolyte imbalance Off pathway: Consider outpatient referral to Neurology Off pathway: Provoked? Yes Address provoking factors No Continue to new onset unprovoked seizure algorithm on p.2 NEED REAL TIME HELP? CALL US! Call ‘OneCall’ at 720-777-3999 or 719-305-3999 (Colorado Springs) Page 1 of 17 CLINICAL PATHWAY ALGORITHM 2. NEW ONSET UNPROVOKED SEIZURE Inclusion Criteria • Age 6 months to 21 years New onset unprovoked • First-time unprovoked seizure seizure • Newly recognized seizure or epilepsy syndrome Exclusion Criteria • Provoked seizure: any seizure as a symptom of fever/illness, acute traumatic brain injury (TBI), Has central nervous system (CNS) infection, tumor, patient returned ingestion, intoxication, or electrolyte imbalance Consult inpatient • to baseline within No -

Myoclonic Atonic Epilepsy Another Generalized Epilepsy Syndrome That Is “Not So” Generalized

EDITORIAL Myoclonic atonic epilepsy Another generalized epilepsy syndrome that is “not so” generalized John M. Zempel, MD, Myoclonic atonic/astatic epilepsy (MAE), first described have shown predominant thalamic activation PhD well by Doose1 (pronounced dough sah: http://www. and default mode network deactivation.6–8 Even Tadaaki Mano, MD, PhD youtube.com/watch?v5hNNiWXV2wF0), is a general- Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, a devastating epileptic ized electroclinical syndrome with early onset charac- encephalopathy with EEG findings of runs of slow terized by myoclonic, atonic/astatic, generalized spike and wave and paroxysmal higher frequency Correspondence to tonic-clonic, and absence seizures (but not tonic activity, has fMRI correlates that are more focal than Dr. Zempel: [email protected] seizures) in association with generalized spike-wave expected in a syndrome with widespread EEG (GSW) discharges. Thought to have a genetic com- abnormalities.9,10 Neurology® 2014;82:1486–1487 ponent that has proven to be complicated,2 MAE EEG-fMRI is maturing as a research and clinical sometimes occurs in children who have otherwise technique. Recording scalp EEG in an electrically been developing normally and has variable outcome. hostile environment is not an easy task. Substantial MAE is typically treated with antiseizure medications technical artifacts, such as changing imaging gradients that are used for generalized epilepsy syndromes, with and ballistocardiogram (ECG-linked artifact observed perhaps a best response to valproate, felbamate, or the in the scalp electrodes), contaminate the EEG signal. ketogenic diet.3,4 However, the relatively distinctive EEG discharges in In this issue of Neurology®, Moeller et al.5 report patients with epilepsy have partially circumvented on the fMRI correlates of GSW discharges as mea- this problem. -

Epilepsy After Stroke

Stroke Helpline: 0303 3033 100 Website: stroke.org.uk Epilepsy after stroke In the first few weeks after a stroke some people have a seizure, and a small number go on to develop epilepsy – a tendency to have repeated seizures. These can usually be completely controlled with treatment. This factsheet explains what epilepsy is, the different types of seizures, and how epilepsy is diagnosed and treated. It also includes advice about coping with a seizure, and a glossary. Epilepsy is a tendency to have repeated What causes seizures? seizures – sometimes called ‘fits’ or ‘attacks’. It affects just under one per cent Cells in the brain communicate with one of people in the UK. Stroke is one of many another and with our muscles by passing conditions that can lead to epilepsy. electrical signals along nerve fibres. If you have epilepsy this electrical activity can Around five per cent of people who have a become disordered. A sudden abnormal stroke will have a seizure within the following burst of electrical activity in the brain can few weeks. These are known as acute or lead to a seizure. onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke. You are more likely There are over 40 different types of seizures to have one if you have had a severe stroke, ranging from tingling sensations or ‘going a stroke caused by bleeding in the brain (a blank’ for a few seconds, to shaking and haemorrhagic stroke), or a stroke involving losing consciousness. the part of the brain called the cerebral cortex. If you have an onset seizure, it This can mean that epilepsy is sometimes does not necessarily mean you have or will confused with other conditions, including develop epilepsy. -

“Seizures (Epilepsy)” a Seizure: Partial – Start in a Specific Part of the Brain, Not in the Whole � Is a Symptom of an Electrical Disturbance in the Brain Brain

“Seizures (Epilepsy)” A seizure: Partial – start in a specific part of the brain, not in the whole Is a symptom of an electrical disturbance in the brain brain. Unlike generalized seizures, partial seizures can have a Is a rare event warning before they occur (aura). Auras are actually a kind of Has a typical beginning (best clue for accurate diagnosis) seizure. There are several different kinds of partial seizures: Is involuntary simple (motor, sensory or psychological), complex, partial Lasts only a short time (90% complete in 90 seconds) seizure with secondary generalization. May cause post seizure impairments. Most seizures do not involve convulsions. Accurate seizure diagnosis by the health care provider is very The most common type of seizure is one mostly involving important because the medications used to treat seizures often vary loss of awareness. depending on the type. There are 20 types of seizures in the Seizures can be very subtle and hard to notice. International Classification of Seizures (over 2,000 types reported in the literature). Examples of post-seizure impairments: A detailed description of the seizure by the person observing the Post ictal confusion (length is individual) seizure is necessary for accurate diagnosing. Having a seizure while in Initial difficulty speaking the doctor’s office is very rare. Confusion about when, where, or what was just happening Memory disturbance which can last a while (behaving Seizure observation: - 3 important ones to make (in order of usual normally but can’t retain/absorb information) importance): Headache with some kinds of seizures What happened right as the seizure was beginning? What is epilepsy? What happened after the seizure was over? What happened during the seizure? Epilepsy is a condition where a person has “recurrent, unprovoked” seizures. -

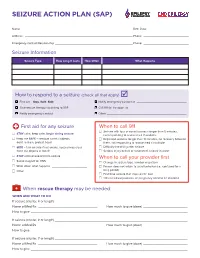

Seizure Action Plan (Sap)

SEIZURE ACTION PLAN (SAP) Name: ——————————————————————————————————————————————————— Birth Date: ——————————————————— Address: —————————————————————————————————————————————————— Phone: ————————————————————— Emergency Contact/Relationship ———————————————————————————————————— Phone: ————————————————————— Seizure Information Seizure Type How Long It Lasts How Often What Happens How to respond to a seizure (check all that apply) F First aid – Stay. Safe. Side. F Notify emergency contact at ______________________________ F Give rescue therapy according to SAP F Call 911 for transport to __________________________________________ F Notify emergency contact F Other ________________________________________________ First aid for any seizure When to call 911 F Seizure with loss of consciousness longer than 5 minutes, F STAY calm, keep calm, begin timing seizure not responding to rescue med if available F Keep me SAFE – remove harmful objects, F Repeated seizures longer than 10 minutes, no recovery between don’t restrain, protect head them, not responding to rescue med if available F SIDE – turn on side if not awake, keep airway clear, F Difficulty breathing after seizure don’t put objects in mouth F Serious injury occurs or suspected, seizure in water F STAY until recovered from seizure When to call your provider first F Swipe magnet for VNS F Change in seizure type, number or pattern F Write down what happens _____________________ F Person does not return to usual behavior (i.e., confused for a F Other _____________________________________ long -

Managing Children with Epilepsy School Nurse Guide

MANAGING CHILDREN WITH EPILEPSY SCHOOL NURSE GUIDE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS TO THOSE WHO HAVE CONTRIBUTED TO THE NOTEBOOK Children’s Hospital of Orange County Melodie Balsbaugh, RN Sue Nagel, RN Giana Nguyen, CHOC Institutes Fullerton School District Jane Bockhacker, RN Orange Unified School District Andrea Bautista, RN Martha Boughen, RN Karen Hanson, RN TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EPILEPSY What is epilepsy? Facts about epilepsy Basic neuroanatomy overview Classification of epileptic seizures Diagnostic Tests II. TREATMENT Medications Vagus Nerve Stimulation Ketogenic Diet Surgery III. SAFETY First Aid IV. SPECIAL CONCERNS MedicAlert Helmets Driving Employment and the law V. EPILEPSY AT SCHOOL School epilepsy assessment tool Seizure record Teaching children about epilepsy lesson plan Creating your own individualized health care plan VI. RESOURCES/SUPPORT GROUPS VII. ACCESS TO HEALTHCARE CHOC Epilepsy Center After-Hours Care After Hours Health Care Advice Healthy Families California Kids MediCal CHOC Clinics Healthy Tomorrows VIII. REFERENCES EPILEPSY WHAT IS EPILEPSY? Epilepsy is a neurological disorder. The brain contains millions of nerve cells called neurons that send electrical charges to each other. A seizure occurs when there is a sudden and brief excess surge of electrical activity in the brain between nerve cells. This results in an alteration in sensation, behavior, and consciousness. Seizures may be caused by developmental problems before birth, trauma at birth, head injury, tumor, structural problems, vascular problems (i.e. stroke, abnormal blood vessels), metabolic conditions (i.e. low blood sugar, low calcium), infections (i.e. meningitis, encephalitis) and idiopathic causes. Children who have idiopathic seizures are most likely to respond to medications and outgrow seizures. -

Psychotic Disorder Due to Lafora Disease: a Case Report

2015 iMedPub Journals Clinical Psychiatry http://www.imedpub.com Vol. 1 No. 1:2 Psychotic Disorder Due to Lafora Şafak Taktak1 , 2 Disease: A Case Report Mustafa Karakuş 1 Psychiatry Department, Ahi Evran University Education and Research Hospital, Turkey 2 Forensic Medicine and Emergency Medicine Department, Yenimahalle Abstract Education and Research Hospital, Turkey Lafora disease is a type of progressive myoclonic epilepsy with poor prognosis, characterized by myoclonus, seizures, cerebellar ataxia and mental disorder. Lafora disease frequently develops at 10-18 years of age and tranmission is autosomal recessive. The first symptoms are usually Corresponding author: Şafak Taktak myoclonic, tonic-clonic, atonic or absence seizures. Epilepsy in children and adolescents with depression, anxiety disorders, attention deficit Psychiatry Department, Ahi Evran hyperactivity disorder can be seen relatively frequently. More rarely, these University Education and Research people can be seen in psychotic disorders. In this paper, we aimed to draw Hospital, Turkey attention to diagnosis of fatal, resistance to treatment with serious suicide attempt and diagnosis of Lafora developing psychotic symptoms in children. [email protected] Tel: 05054037967 Introduction from effective treatment and resulting in death was reported , as Epilepsy in childhood, with prevalence 0,5-1 %, are among the a case report [1-11]. most common neurological diagnosis. Progressive myoclonic constitutes less than 1% of all epilepsies, while Lafora disease Case constitutes 10% of all epilepsies. Lafora disease is a type of progressive myoclonic epilepsy with poor prognosis, characterized The index case, a 12-year-old girl, who had a family history of by myoclonus, seizures, cerebellar ataxia and mental disorder. -

Evaluation of Behavior and Cognitive Function in Children with Myoclonic

& The ics ra tr pe ia u Niimi et al., Pediat Therapeut 2013, 3:3 t i d c e s P DOI: 10.4172/2161-0665.1000159 Pediatrics & Therapeutics ISSN: 2161-0665 Case Report Open Access Evaluation of Behavior and Cognitive Function in Children with Myoclonic Astatic Epilepsy Taemi Niimi1, Yuji Inaba1, Mitsuo Motobayashi1, Takafumi Nishimura1, Naoko Shiba1, Tetsuhiro Fukuyama2, Tsukasa Higuchi3, and Kenichi Koike1 1Department of Pediatrics, Shinshu University School of Medicine, Matsumoto, Japan 2Department of Pediatric Neurology, Nagano Children’s Hospital, Azumino, Japan 3Department of General Pediatrics, Nagano Children’s Hospital, Azumino, Japan Abstract Background: Myoclonic astatic epilepsy (MAE) is an idiopathic and generalized childhood epileptic syndrome. Although several studies have reported on cognitive function and intellectual outcome in MAE, little is known about the behavioral problems associated with this disease. The aim of this study was to clarify behavior and cognitive function in children with MAE. Methods: Four children who were diagnosed as having MAE using the proposed criteria of the International Classification of Epilepsies were retrospectively analyzed using patient records with regard to clinical and neuropsychological findings such as age of seizure onset, semiology and severity of seizures, treatment course, behavioral problems, EEG findings, and WISC-III and Pervasive Developmental Disorders Autism Society Japan Rating Scale (PARS) scores that indicate the tendency of autistic behaviors. Results: Disease onset in our cohort ranged from 9 to 35 months of age. Seizures were controlled within 3-8 months over a follow-up period of 4-12 years. All patients had borderline normal intelligence (mean IQ: 75.8 at 5-7 years of age) and exhibited impaired coordination, clumsiness, hyperactivity or impulsivity, and impaired social interaction after improvement of seizures.