Economic and Social Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2008

cover_asia_report_2008_2:cover_asia_report_2007_2.qxd 28/11/2008 17:18 Page 1 Central Committee for Drug Lao National Commission for Drug Office of the Narcotics Abuse Control Control and Supervision Control Board Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 500, A-1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43 1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43 1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org Opium Poppy Cultivation in South East Asia Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand OPIUM POPPY CULTIVATION IN SOUTH EAST ASIA IN SOUTH EAST CULTIVATION OPIUM POPPY December 2008 Printed in Slovakia UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme (ICMP) promotes the development and maintenance of a global network of illicit crop monitoring systems in the context of the illicit crop elimination objective set by the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Drugs. ICMP provides overall coordination as well as direct technical support and supervision to UNODC supported illicit crop surveys at the country level. The implementation of UNODC's Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme in South East Asia was made possible thanks to financial contributions from the Government of Japan and from the United States. UNODC Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme – Survey Reports and other ICMP publications can be downloaded from: http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/crop-monitoring/index.html The boundaries, names and designations used in all maps in this document do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. This document has not been formally edited. CONTENTS PART 1 REGIONAL OVERVIEW ..............................................................................................3 -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

UNDERCURRENTS Monitoring Development on Burma’S Mekong

UNDERCURRENTS Monitoring Development on Burma’s Mekong INSIDE: Blasting the Mekong Consequences of the Navigation Scheme Road Construction in Shan State: Turning Illegal Drug Profits into Legal Revenues Sold Down the River The tragedy of human trafficking on the Mekong No Place Left for the Spirits of the Yellow Leaves Intensive logging leaves few options for the Mabri people in Shan State ...and more The Lahu National Development January 2005 Organization (LNDO) The Mekong/ Lancang The Mekong River is Southeast Asia’s longest, stretching from its source in Tibet to the delta of Vietnam. Millions of people depend on it for agriculture and fishing, and accordingly it holds a special cultural significance. For 234 kilometers, the Mekong forms the border between Burma’s Shan State and Luang Nam Tha and Bokeo provinces of Laos. This stretch includes the infamous “Golden Triangle”, or where Burma, Laos and Thailand meet, which has been known for illicit drug production. Over 22,000 primarily indigenous peoples live in the mountainous region of this isolated stretch of the river in Burma. The main ethnic groups are Akha, Shan, Lahu, Sam Tao (Loi La), Chinese, and En. The Mekong River has a special significance for the Lahu people. Like the Chinese, we call it the Lancang, and according to legends, the first Lahu people came from the river’s source. Traditional songs and sayings are filled with references to the river. True love is described as stretching form the source of the Mekong to the sea. The beauty of a woman is likened to the glittering scales of a fish in the Mekong. -

Show Business — Shan Herald Agency for News (S.H.A.N.) 22.02.11 13:08

Show Business — Shan Herald Agency for News (S.H.A.N.) 22.02.11 13:08 SHOW BUSINESS Rangoon's "War on Drugs" in Shan State A report by The Shan Herald Agency for News (S.H.A.N.) - An independent media group - "When kings are unrighteous, http://www.shanland.org/oldversion/index-3160.htm Seite 2 von 41 Show Business — Shan Herald Agency for News (S.H.A.N.) 22.02.11 13:08 The moon and the sun go wrong in their courses." The Buddha, Anguttara Nikaya EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This investigative report exposes as a charade the Burmese military regime's "War on Drugs" in Shan State. It provides evidence that the drug industry is integral to the regime's political strategy to pacify and control Shan State, and concludes that only political reform can solve Burma's drug problems. In order to maintain control of Shan State without reaching a political settlement with the ethnic peoples, the regime is allowing numerous local ethnic militia and ceasefire organisations to produce drugs in exchange for cooperation with the state. At the same time, it condones involvement of its own personnel in the drug business as a means of subsidizing its army costs at the field level, as well as providing personal financial incentives. These policies have rendered meaningless the junta's recent "anti-drug" campaign, staged mainly in Northern Shan State since 2001. The junta deliberately avoided targeting areas under the control of its main ceasefire and militia allies. The people most affected have been poor opium farmers in "unprotected" areas, who have suffered mass arrest and extrajudicial killing. -

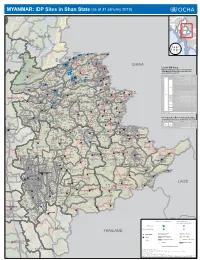

IDP Sites in Shan State (As of 31 January 2019)

MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Shan State (as of 31 January 2019) BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH Nay Pyi Taw LAOS KACHIN THAILAND Pang Hseng Man Kin (Kyu Koke) Monekoe SAGAING Kone Ma Na Maw Hteik 21 Nawt Ko Pu Wan Nam Kyar Mon Hon Tee Yi Hku Ngar Oe Nam War Manhlyoe 22 23 Nam Kut Char Lu Keng Aik Hpan Shwe Kyaung Kone U Yin Pu Nam Kat 36 (Manhero) Man Hin ☇ Muse Pa Kon War Yawng San Hsar Muse Konkyan Kun Taw 37 Man Mei ☇ Long Gam Man Ton ☇34 Tar Ku Ti Thea Chaung Namhkan 35 KonkyanTar Shan ☇ Man Set Kyu Pat 11 26 28 Au Myar Loi Mun Ton Bar 27 Yae Le Lin Lai 25 29 Hsi Hsar Hsin Keng Yan Long Keng CHINA Ho Nar Pang Mawng Long Htan Baing Law Se Long Nar Hpai Pwe Za Meik Khaw Taw HumLaukkaing Htin List of IDP Sites Aw Kar Pang Mu Shwe Htu Namhkan Kawng Hkam Nar Lel Se Kin 14 Bar Hpan Man Tet 15 Man Kyu Baing Bin Yan Bo (Lower) Nam Hum Tar Pong Ho Maw Ho Et Kyar Ti Lin Data provided by the Camp Coordination and Pang Hkan Hing Man Nar Hin Lai 4 Kutkai Nam Hu Man Sat Man Aw Mar Li Lint Ton Kwar 24 Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster based on Pin Kyein (Ywar Thit) Ho Pang 8 Hseng Hkawng Laukkaing Mabein 17 Man Hwei Si Ping Man Kaw Kaw Yi Hon Gyet Hopong Hpar Pyint Nar Ngu Long Htan update of 31 January 2018 Lawt Naw 9 Hko Tar Ma Waw 10 Tarmoenye Say Kaw Man Long Maw Han Loi Kan Ban Nwet Pying Kut Mabein Su Yway Namtit No. -

Myanmar Languages | Ethnologue

7/24/2016 Myanmar Languages | Ethnologue Myanmar LANGUAGES Akeu [aeu] Shan State, Kengtung and Mongla townships. 1,000 in Myanmar (2004 E. Johnson). Status: 5 (Developing). Alternate Names: Akheu, Aki, Akui. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Ngwi-Burmese, Ngwi, Southern. Comments: Non-indigenous. More Information Akha [ahk] Shan State, east Kengtung district. 200,000 in Myanmar (Bradley 2007a). Total users in all countries: 563,960. Status: 3 (Wider communication). Alternate Names: Ahka, Aini, Aka, Ak’a, Ekaw, Ikaw, Ikor, Kaw, Kha Ko, Khako, Khao Kha Ko, Ko, Yani. Dialects: Much dialectal variation; some do not understand each other. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Ngwi-Burmese, Ngwi, Southern. More Information Anal [anm] Sagaing: Tamu town, 10 households. 50 in Myanmar (2010). Status: 6b (Threatened). Alternate Names: Namfau. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Sal, Kuki-Chin-Naga, Kuki-Chin, Northern. Comments: Non- indigenous. Christian. More Information Anong [nun] Northern Kachin State, mainly Kawnglangphu township. 400 in Myanmar (2000 D. Bradley), decreasing. Ethnic population: 10,000 (Bradley 2007b). Total users in all countries: 450. Status: 7 (Shifting). Alternate Names: Anoong, Anu, Anung, Fuchve, Fuch’ye, Khingpang, Kwingsang, Kwinp’ang, Naw, Nawpha, Nu. Dialects: Slightly di㨽erent dialects of Anong spoken in China and Myanmar, although no reported diഡculty communicating with each other. Low inherent intelligibility with the Matwang variety of Rawang [raw]. Lexical similarity: 87%–89% with Anong in Myanmar and Anong in China, 73%–76% with T’rung [duu], 77%–83% with Matwang variety of Rawang [raw]. Classi囕cation: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Central Tibeto-Burman, Nungish. Comments: Di㨽erent from Nung (Tai family) of Viet Nam, Laos, and China, and from Chinese Nung (Cantonese) of Viet Nam. -

Weekly Security Review

The information in this report is correct as of 8.00 hours (UTC+6:30) 8 July 2020. Weekly Security Review Safety and Security Highlights for Clients Operating in Myanmar Dates covered: 2 July– 8 July 2020 The contents of this report are subject to copyright and must not be reproduced or shared without approval from EXERA. The information in this report is intended to inform and advise; any mitigation implemented as a result of this information is the responsibility of the client. Questions or requests for further information can be directed to [email protected]. COMMERCIAL-IN-CONFIDENCE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Covid -19 pandemic When EXERA released its latest Weekly Security Review (WSR) on 2 July 2020 at 10:09 hrs, Myanmar had a total of 299 Covid-19 patients since the beginning of the pandemic, i.e. 7 more than the previous week. As of 8 July, at 08:00 Hrs, 316 confirmed cases have been reported since the beginning of the epidemic, i.e. 17 new cases in the last week. All of them came back from other countries. The week was marked by the laudatory comments of UNWHO representative in Myanmar about the crisis management by the government, by the suicide of one man in quarantine centre, by the lawsuit against Pastor David Lah, and by the postponement of debt repayment by Myanmar decided by EU countries. Internal Conflict This week saw a relative lull of armed clashes in Rakhine State. However, disappearances and arrests of civilians went unabated. The situation of IDPs is increasingly concerning. In Northern Shan State, last week clashes went to a temporary stop. -

Jadeand Conflict

JADE AND CONFLICT Myanmar’s Vicious Circle June 2021 2 CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS / MAIN ARMED ORGANISATIONS ACTIVE IN THE JADE SECTOR .................. 4 MAP OF MYANMAR ............................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 1. JADE AND CONFLICT: MYANMAR’S VICIOUS CIRCLE ...................................................................... 10 1.1 The NLD attempts to break the jade-conflict nexus ..................................................................................... 10 1.2 Mining reform derailed .................................................................................................................................. 11 Case Study: The 2019 Gemstone Law ........................................................................................................... 12 Case Study: State watchdog MGE keeps cosy industry ties rife with conflicts of interest .......................... 18 1.3 Jade after the coup ........................................................................................................................................ 22 2. ARMED GROUPS HOOKED ON JADE REVENUES .............................................................................. 26 2.1 The Tatmadaw profits from control over mining ........................................................................................ -

Aftershocks Along Burma's Mekong

AFTERSHOCKS ALONG BURMA’S MEKONG Reef-blasting and military-style development in Eastern Shan State The Lahu National Development Organisation August 2003 The Lahu National Development Organisation The Lahu National Development Organisation was set up by a group of leading Lahu democracy activists in Chiang Mai, Thailand, in March 1997 to promote the welfare and well-being of the Lahu people, including the promotion of alternatives to growing opium. The objectives of the LNDO are: • To promote democracy and human rights in Shan State, with particular attention paid to the Lahu • To promote increased understanding among the Lahu, Wa, Pa-O, Palaung and Shan of human rights, democracy, federalism, community development and health issues • To develop unity and cooperation among the Lahu and other highlanders from Shan State and to provide opportunities for development of civic leadership skills among local groups. Contact details P.O. Box 227, Chiang Mai GPO, Thailand 50000, e-mail: [email protected] cover design based on photo of Mekong blasting from www.chiangrai.com CONTENTS Introduction....................................................................................................................1 Executive Summary........................................................................................................3 The Upper Mekong Navigation Improvement Project.....................................................4 Background of the project....................................................................................4 Environmental -

Show Business

SHOW BUSINESS Rangoon's "War on Drugs" in Shan State A report by The Shan Herald Agency for News (S.H.A.N.) - An independent media group - "When kings are unrighteous, The moon and the sun go wrong in their courses." The Buddha, Anguttara Nikaya 2 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This investigative report exposes as a charade the Burmese military regime's "War on Drugs" in Shan State. It provides evidence that the drug industry is integral to the regime's political strategy to pacify and control Shan State, and concludes that only political reform can solve Burma's drug problems. In order to maintain control of Shan State without reaching a political settlement with the ethnic peoples, the regime is allowing numerous local ethnic militia and ceasefire organisations to produce drugs in exchange for cooperation with the state. At the same time, it condones involvement of its own personnel in the drug business as a means of subsidizing its army costs at the field level, as well as providing personal financial incentives. These policies have rendered meaningless the junta's recent "anti-drug" campaign, staged mainly in Northern Shan State since 2001. The junta deliberately avoided targeting areas under the control of its main ceasefire and militia allies. The people most affected have been poor opium farmers in "unprotected" areas, who have suffered mass arrest and extrajudicial killing. The anti-drug campaign was not waged at all in Southern Shan State, and in only a few token areas of Eastern Shan State. Opium is continuing to be grown in almost every township of Shan State, with Burmese military personnel involved at all levels of opium production and trafficking, from providing loans to farmers to grow opium, taxation of opium, providing security for refineries, to storage and transportation of heroin. -

Southeast Asia Opium Survey 2015

Central Committee for Lao National Commission for Drug Abuse control Drug Control and Supervision Southeast Asia Opium Survey 2015 Lao PDR, Myanmar In Southeast Asia, UNODC supports Member States to develop and implement evidence based rule of law, drug control and criminal justice responses through the Regional Programme 2014‐2017. UNODC’s Illicit Crop Monitoring Programming (ICMP) promotes the development and maintenance of a global network of illicit crop monitoring systems. The implementation of UNODC’s Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme in Southeast Asia has been made possible with financial contributions from the Governments of Japan and the United States of America. UNODC Illicit Crop Monitoring Programme – Survey Reports and other ICMP publications can be downloaded from: http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/crop‐monitoring/index.html UNODC Regional Office for Southeast Asia and the Pacific Telephone: +6622882100 Fax: +6622812129 Email: [email protected] Website: www.unodc.org/southeastasiaandpacific Twitter: @UNODC_SEAP The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNODC concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The cover was designed by Akara Umapornsakula. Contents Part 1 – Executive Summary and the Way Forward 1. Executive summary .......................................................................................................... -

(A) Kachin State (1) Permitted Areas A. Bhamo Township B. Shwegu

Permitted Areas (a) Kachin State (1) Permitted Areas a. Bhamo Township b. Shwegu Township c. Mogaung Township d. Mohnyin Township e. Myit-kyi-na Township (2) Permitted only in the Downtown Areas a. Putao Township b. Machanbaw Township c. Mansi Township d. Momauk Township e. Waingmaw Township (3) The Areas which need to get the Prior Permission a. Naung-mon Township b. Kawng-lan-hpu Township c. Sumprabum Township d. Hpakant Township e. Tanai Township f. Injangyang Township g. Chipwi Township h. Tsawlaw Township (b) Kayah State (1) Permitted Areas a. Loi-kaw Township b. Demoso Township . Dawkaladu and Taneelalae Village in Dawkalawdu Village Group . Ngwetaung Village in Ngwetaung Village Group . Panpetrwanku, Panpetsaunglu, Panpetpemasaung . Panpetkateku and Panpetdawke Villages (Except these, other areas need to get permission) c. Hpasawng Township . Uptown Quarters in Hpasaung, Bawlakheand Mese . Towns on the bordering- trade way with Thailand . (Except these, other areas need to get permission) d. Bawlakhe Township . Uptown Quarters in Hpasaung, Bawlakheand Mese . Towns on the bordering- trade way with Thailand . (Except these, other areas need to get permission) e. Mese Township . Uptown Quarters in Hpasaung, Bawlakheand Mese . Towns on the bordering- trade way with Thailand . (Except these, other areas need to get permission) (2) Permitted only in the Downtown Areas a. Hpruso Township (3) The Areas which need to get the Prior Permission a. Shadaw Township (c) Kayin State (1) Permitted Areas a. Hpa-an Township b. Mya-wady Township . Su-kali Sub-Township . Wal-lae Sub-Township (2) Permitted only in the Downtown Areas a. Kaw-ka-reik Township . Kyone-doe Sub-Township b.