1 INTRODUCTION in the Summer of 1997, While Performing with The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Aunt” Clara Brown

“Aunt” Clara Brown Often called the “Angel of the Rockies,” Clara Brown reflects the richness of the African-American experience. She faced enormous challenges and reached wonderful heights in her nearly eighty-five years. Turning her back on her life in slavery, she looked west for the children she had lost. She then became one of the first African-American women to settle in Colorado. Clara was skillful in business ventures and investments that earned her thousands of dollars. She also gained a reputation for community care. She helped people of all races, but she worked especially hard to bring black people out of poverty and enslavement. Enslaved Clara Brown was probably born into slavery in Virginia around 1800. Wealthy white southerners who “owned” Clara often auctioned her to the highest bidder as if she were a horse to be sold. Each time she was bought, she would have to move, sometimes even to a different state. Clara married when she was eighteen, and later gave birth to four children. Tragically, all of her children and her husband were sold to different people across the country. She vowed to work for the rest of her life to reunite her shattered family. Clara worked as a domestic servant until 1856 when her “owner” at the time, George Brown, died. Fortunately, his family helped Clara achieve her freedom, and she could begin the search for her missing children. Heading West Hearing that one of her daughters, Eliza, may have moved to the West, Clara headed in that direction. She had money to travel, but black people at the time were forbidden from buying stagecoach tickets. -

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents Exploring the Kit: Description and Instructions for Use……………………...page 2 A Brief History of Mining in Colorado ………………………………………page 3 Artifact Photos and Descriptions……………………………………………..page 5 Did You Know That…? Information Cards ………………………………..page 10 Ready, Set, Go! Activity Cards ……………………………………………..page 12 Flash! Photograph Packet…………………………………………………...page 17 Eureka! Instructions and Supplies for Board Game………………………...page 18 Stories and Songs: Colorado’s Mining Frontier ………………………………page 24 Additional Resources…………………………………………………………page 35 Exploring the Kit Help your students explore the artifacts, information, and activities packed inside this kit, and together you will dig into some very exciting history! This kit is for students of all ages, but it is designed to be of most interest to kids from fourth through eighth grades, the years that Colorado history is most often taught. Younger children may require more help and guidance with some of the components of the kit, but there is something here for everyone. Case Components 1. Teacher’s Manual - This guidebook contains information about each part of the kit. You will also find supplemental materials, including an overview of Colorado’s mining history, a list of the songs and stories on the cassette tape, a photograph and thorough description of all the artifacts, board game instructions, and bibliographies for teachers and students. 2. Artifacts – You will discover a set of intriguing artifacts related to Colorado mining inside the kit. 3. Information Cards – The information cards in the packet, Did You Know That…? are written to spark the varied interests of students. They cover a broad range of topics, from everyday life in mining towns, to the environment, to the impact of mining on the Ute Indians, and more. -

Hearing Nostalgia in the Twilight Zone

JPTV 6 (1) pp. 59–80 Intellect Limited 2018 Journal of Popular Television Volume 6 Number 1 © 2018 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jptv.6.1.59_1 Reba A. Wissner Montclair State University No time like the past: Hearing nostalgia in The Twilight Zone Abstract Keywords One of Rod Serling’s favourite topics of exploration in The Twilight Zone (1959–64) Twilight Zone is nostalgia, which pervaded many of the episodes of the series. Although Serling Rod Serling himself often looked back upon the past wishing to regain it, he did, however, under- nostalgia stand that we often see things looking back that were not there and that the past is CBS often idealized. Like Serling, many ageing characters in The Twilight Zone often sentimentality look back or travel to the past to reclaim what they had lost. While this is a perva- stock music sive theme in the plots, in these episodes the music which accompanies the scores depict the reality of the past, showing that it is not as wonderful as the charac- ter imagined. Often, music from these various situations is reused within the same context, allowing for a stock music collection of music of nostalgia from the series. This article discusses the music of nostalgia in The Twilight Zone and the ways in which the music depicts the reality of the harshness of the past. By feeding into their own longing for the reclamation of the past, the writers and composers of these episodes remind us that what we remember is not always what was there. -

Turning Points in History

Turning Points in history Colorado topic starting points 1. Indian Wars in the Colorado Territory 2. The Gold Rush: How George A. Jackson’s discovery of Gold along Chicago Creek changed Colorado. 3. The consequences of the Sand Creek Massacre—how the aftermath changed Indian relations. 4. The work of the Colorado Prisoner’s Aid Society. 5. How the election of 1904 was a turning point in Colorado politics. 6. Helen Hunt Jackson and her Indian relations reform legacy. 7. How “Honest John” Shaforth, Governor from 1909—1913, changed Colorado. 8. Nathan Meeker and the Ute Indians. 9. A Turning Point in Denver history—the defeat of Mayor Robert Speer. 10. Justina Ford changes health care in Colorado. 11. The Homestead Act—How Homesteading won the west. 12. How Executive order 9066 affected Japanese Americans living in Colorado. 13. The impact of Camp Amache on the farming community of Lamar, Colorado. 14. How the Bonfil sisters’ feud changed philanthropy in Colorado. 15. The treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo cedes the Southwest to the United States. 16. The Christmas Day 1854 massacre at Ft. Pueblo. 17. Nathaniel Hill’s Blackhawk smelter ushered in the hard-rock mining era in Colorado. 18. Irrigation farming—a turning point in dryland farming. 19. Women’s voting rights in the west. (Wyoming was first, but Colorado was second.) 20. How “Home Rule” changed Denver. 21. Changed Opportunities: The Emily Griffith School. 22. The Battle of Ludlow—the coal mine strike of 1914 changed worker rights. 23. The Denver Tramway strike of 1920. 24. The Child Labor amendment to the federal constitution, and the role Colorado played in its attempted ratification. -

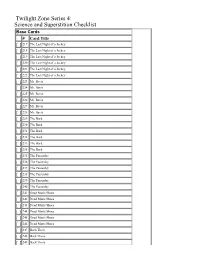

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred -

A Teacher's Guide

A TEACHER’S GUIDE • Field Trips • Workshops • Performances • Assemblies DOWNLOAD THE 2015-2016 DIRECTORY AT SCFD.ORG AND SCCOLLABORATIVE.ORG 20152016 DIRECTORY OF EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES FOR TEACHERS AND SCHOOLS Sponsored by the cultural organizations of the Scientific and Cultural Collaborative (SCC) HOW TO USE THE SCC DIRECTORY FOR TEACHERS AND SCHOOLS How to use the Directory: Look under major subject headings and then under grade levels to find appropriate programming. Remember to look under “Adaptable to grade” for additional K-12 programs. 1. Contact the organization directly to schedule a program with possible dates and number of students. 2. Neither the SCFD nor SCC are responsible for errors. Copyright 2015 and 2016. Questions about the Directory (not individual programs or bookings): SCC Coordinator, Charlotte D’Armond Talbert, 303-519-7772, [email protected] Photos on the cover provided by (clockwise from top left) Denver Art Museum (photo by Christina Jackson), WOW! Children’s Museum (photo by Daniel Hirsh/West End Photography) and Colorado Mountain Club (photo by Melanie Leggett). INDEX GRADE LEVEL: SUBJECT: All = Adaptable to Grade M = Middle School LA=Language Arts, Humanities and Foreign Language L = Lower Elementary H = High School Arts=Performing and Visual Arts U = Upper Elementary PD = Professional Development SM=Science, Math and Nature for Adults SS=Social Science, History and World Culture ORGANIZATION ORGANIZATION TITLE ................................................................GRADE .....SUBJECT .......PAGE -

Adventure Into the Past, a Search for Colorado's Mining Camps

ADVENTURE INTO THE PAST 11 Adventure Into the Past, A Search For Colorado's Mining Camps MURIEI... SIBELL \Y OLLE'::· In 1926, when I came to Colorado from the East, I bad never heard of a ghost town, but on one of my first mountain drives I was shown Central City and was told something of its history. I had always been interested in architecture, and the skeletal shell of the once booming town fascinated me. I liked the Victorian houses, set tidily along the streets; the few active stores flanked by many empty ones; the rusty mills, and the rows of deserted buildings perched high above Eureka Gulch. Central City was not entirely deserted, in fact it never has been; but so little of its former glory remained that the footsteps of those living in it echoed loudly on the board sidewalks, and at night only an occasional window showed a lighted interior. The place was full of echoes, and memories, and history, and I felt strangely stirred by it. Here was a piece of the Old West, a tangible witness of Colorado's pioneering achievement. It was disappearing fast; it was important, it should be preserved; it challenged me. Someone should record it before it decayed or was "restored" to twentieth century needs. 'l'he place itself seemed to cry out for a pictorial rendering and I determined then and there to try my hand at it and to return in September to sketch the streets and individual buildings. Furthermore, I decided to return again and again until I had Central City on paper. -

Fade In: Int. Art Gallery – Day

FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY Exhibition Guide FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY March 03 – May 08, 2016 Works by Danai Anesiadou, Nairy Baghramian, Michael Bell-Smith, Dora Budor, Heman Chong, Mike Cooter, Brice Dellsperger, GALA Committee, Mathis Gasser, Jamian Juliano-Villani, Bertrand Lavier, William Leavitt, Christian Marclay, Rodrigo Matheus, Allan McCollum, Henrique Medina, Carissa Rodriguez, Cindy Sherman, Amie Siegel, Scott Stark, and Albert Whitlock; performances and public programs by Casey Jane Ellison, Mario García Torres, Alex Israel, Thirteen Black Cats, and more. Recasting the gallery as a set for dramatic scenes, FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY explores the role that art plays in narrative film and television. FADE IN features the work of 25 artists and considers a history of art as seen in classic movies, soap operas, science fiction, pornography and musicals. These works have been sourced, reproduced and created in response to artworks that have been made to appear on-screen, whether as props, set dressings, plot devices, or character cues. The nature of the exhibition is such that sculptures, paintings and installations transition from prop to image to art object, staging an enquiry into whether these fictional depictions in mass media ultimately have greater influence in defining a collective understanding of art than art itself does. Certain preoccupations with artworks are established early on in cinematic history: the preciousness of art objects anchors their roles as plot drivers, and anxieties intensify regarding the vitality of artworks and their perceived abilities to wield power over viewers or to capture spirits. Such themes were famously explored in the 1945 film adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, from which Cindy Sherman has sourced the original portrait painted for the production. -

THE COLORADO MAGAZINE Published Quarterly by the State Historical Society of Colorado

THE COLORADO MAGAZINE Published Quarterly by The State Historical Society of Colorado Vol. XXXV Denver, Colorado, July, 1958 Number 3 A Pioneer in Colorado and Wy01ning By AMANDA HARDIN BROWN Assisted by MARGARET ISAAC I. Often in a family there is at least one member who collects and preserves family history and photographs. Mrs. Margaret Isaac of Denver is the member of her family who has been doing those things for a number of years. Mrs. Isaac, a native of Meeker, Colorado, is a graduate of the University of Denver, and has collected much Colo rado history. She makes her home with her husband, Gerhard J. Isaac, and their two sons, John and David. Through Mrs. Isaac's intense interest in western history she encouraged her Great-aunt, Mrs. Amanda Hardin Brown, to relate her pioneering experiences for permanent preservation. Amanda Hardin was the daughter of John Hardin, a native of Kentucky, who grew up in Missouri, on a farm. In 1847, when he was twenty-one years of age, he joined a party of traders and went over land to California. After working in the mines there for two years, he returned to the States by way of the Isthmus of Panama. On June 22, 1852, John Hardin married Sarah J. Hand. In 1864 he brought his family to Colorado. Amanda, fourth child of John and Sarah Hardin, told many incidents of her life to Mrs. Isaac, who wove them into a whole, and has made the story available for publication.-Editor. I was born November 21, 1862, on my Father's farm, two and one-half miles from the little town of Bethany, in Harrison County, Missouri. -

Friends Historic Riverside Emetery C

FRIENDSof HISTORIC RIVERSIDE CEMETERY Highlights of Riverside A walking (or driving) tour October 31st, 2009 The Friends of Historic Riverside Cemetery is a volunteer run, member supported, non-profit organization dedicated to promoting awareness and preservation of Denver’s oldest cemetery. Join us on the web at friendsofriversidecemetery.org About Riverside Historic Riverside Cemetery is Denver’s oldest Riverside was dedicated as a National Historic District operating cemetery. Founded in 1876, the burial in 1992. In 2001, Riverside lost its Platte River water grounds were intended to be a parklike cemetery, and a rights. Without water, the historic landscape has respectable resting spot to replace the blighted pioneer suffered a staggering loss of trees and turf. The once cemetery, Mount Prospect (now Cheesman Park). lush turf grass is all but gone from the property, leaving only weeds and patches of native grass as groundcover. The cemetery is 77 developed acres and the last resting place for over 67,000 people. There are markers for In 2008, Riverside Cemetery was listed as one of about half of those buried here. Colorado’s “Most Endangered Places” by Colorado Preservation, Inc., and in October 2009 The Cultural The chapel, office and crematory were built in 1904; at Landscape Foundation recognized Riverside as a the time, it was the only crematory between St. Louis “Shaper of the American Landscape”. The purpose and San Francisco. It was used until 1950. of this award to draw “attention to endangered (or threatened) nationally significant cultural landscapes.” One of the most unique treasures of Riverside Cemetery is the largest number and wide variety of Frequently Asked Questions zinc markers at any cemetery in the world. -

BENNY GOLSON NEA Jazz Master (1996)

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. BENNY GOLSON NEA Jazz Master (1996) Interviewee: Benny Golson (January 25, 1929 - ) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: January 8-9, 2009 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 119 pp. Brown: Today is January 8th, 2009. My name is Anthony Brown, and with Ken Kimery we are conducting the Smithsonian National Endowment for the Arts Oral History Program interview with Mr. Benny Golson, arranger, composer, elder statesman, tenor saxophonist. I should say probably the sterling example of integrity. How else can I preface my remarks about one of my heroes in this music, Benny Golson, in his house in Los Angeles? Good afternoon, Mr. Benny Golson. How are you today? Golson: Good afternoon. Brown: We’d like to start – this is the oral history interview that we will attempt to capture your life and music. As an oral history, we’re going to begin from the very beginning. So if you could start by telling us your first – your full name (given at birth), your birthplace, and birthdate. Golson: My full name is Benny Golson, Jr. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The year is 1929. Brown: Did you want to give the exact date? Golson: January 25th. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 Brown: That date has been – I’ve seen several different references. Even the Grove Dictionary of Jazz had a disclaimer saying, we originally published it as January 26th. -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films.