WC Fields from the Ziegfeld Follies And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Will Rogers and Calvin Coolidge

Summer 1972 VoL. 40 No. 3 The GfJROCEEDINGS of the VERMONT HISTORICAL SOCIETY Beyond Humor: Will Rogers And Calvin Coolidge By H. L. MEREDITH N August, 1923, after Warren G. Harding's death, Calvin Coolidge I became President of the United States. For the next six years Coo lidge headed a nation which enjoyed amazing economic growth and relative peace. His administration progressed in the midst of a decade when material prosperity contributed heavily in changing the nature of the country. Coolidge's presidency was transitional in other respects, resting a bit uncomfortably between the passions of the World War I period and the Great Depression of the I 930's. It seems clear that Coolidge acted as a central figure in much of this transition, but the degree to which he was a causal agent, a catalyst, or simply the victim of forces of change remains a question that has prompted a wide range of historical opinion. Few prominent figures in United States history remain as difficult to understand as Calvin Coolidge. An agrarian bias prevails in :nuch of the historical writing on Coolidge. Unable to see much virtue or integrity in the Republican administrations of the twenties, many historians and friends of the farmers followed interpretations made by William Allen White. These picture Coolidge as essentially an unimaginative enemy of the farmer and a fumbling sphinx. They stem largely from White's two biographical studies; Calvin Coolidge, The Man Who Is President and A Puritan in Babylon, The Story of Calvin Coolidge. 1 Most notably, two historians with the same Midwestern background as White, Gilbert C. -

Movie Mirror Book

WHO’S WHO ON THE SCREEN Edited by C h a r l e s D o n a l d F o x AND M i l t o n L. S i l v e r Published by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., I n c . NEW YORK CITY t y v 3. 67 5 5 . ? i S.06 COPYRIGHT 1920 by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., Inc New York A ll rights reserved | o fit & Vi HA -■ y.t* 2iOi5^ aiblsa TO e host of motion picture “fans” the world ovi a prince among whom is Oswald Swinney Low sley, M. D. this volume is dedicated with high appreciation of their support of the world’s most popular amusement INTRODUCTION N compiling and editing this volume the editors did so feeling that their work would answer a popular demand. I Interest in biographies of stars of the screen has al ways been at high pitch, so, in offering these concise his tories the thought aimed at by the editors was not literary achievement, but only a desire to present to the Motion Picture Enthusiast a short but interesting resume of the careers of the screen’s most popular players, rather than a detailed story. It is the editors’ earnest hope that this volume, which is a forerunner of a series of motion picture publications, meets with the approval of the Motion Picture “ Fan” to whom it is dedicated. THE EDITORS “ The Maples” Greenwich, Conn., April, 1920. whole world is scene of PARAMOUNT ! PICTURES W ho's Who on the Screcti THE WHOLE WORLD IS SCENE OF PARAMOUNT PICTURES With motion picture productions becoming more masterful each year, with such superb productions as “The Copperhead, “Male and Female, Ireasure Island” and “ On With the Dance” being offered for screen presentation, the public is awakening to a desire to know more of where these and many other of the I ara- mount Pictures are made. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

TERMINAL DRIVE CELL PHONE WAITING AREA OPENS New Location Improves Access to Terminal

Will Rogers World Airport For Immediate Release: June 15, 2020 For More Information Contact: Joshua Ryan, Public Information & Marketing Coordinator Office: (405) 316-3239 Cell: (405) 394-8926 TERMINAL DRIVE CELL PHONE WAITING AREA OPENS New Location Improves Access to Terminal OKLAHOMA CITY, June 15, 2020 – Last week, construction crews put the final touches on a new cell phone waiting area at Will Rogers World Airport. The new area provides 195 parking spaces, improved access to and from Terminal Drive, LED lighting for enhanced visibility, as well as a flow-through design that maximizes parking and means drivers never have to back in or out of a parking space. Signage on southbound Terminal Drive will direct drivers to the new waiting area. The entrance is just south of the Amelia Earhart Lane intersection. The cell phone waiting area is not only a convenient amenity, it helps to improve traffic circulation at the terminal. More cars in the waiting area usually translates to less congestion in the lanes next to the building. And because city ordinance designates the terminal curbside for active loading and unloading only, use of the waiting area also helps drivers avoid a citation. A quick reminder, proper use of a cell phone waiting area means receiving a passenger’s call or text from the curb before approaching the terminal. The passenger should always be ready to load in the vehicle as soon as the driver arrives. The concept of a cell phone waiting area originated after 9/11 when parking curbside at the terminal was no longer permitted. -

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover Artist Publisher Date Notes Sabbath Chimes (Reverie) F

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover artist Publisher Date Notes Sabbath Chimes (Reverie) F. Henri Klickmann Harold Rossiter Music Co. 1913 Sack Waltz, The John A. Metcalf Starmer Eclipse Pub. Co. [1924] Sadie O'Brady Billy Lindemann Billy Lindemann Broadway Music Corp. 1924 Sadie, The Princess of Tenement Row Frederick V. Bowers Chas. Horwitz J.B. Eddy Jos. W. Stern & Co. 1903 Sail Along, Silv'ry Moon Percy Wenrich Harry Tobias Joy Music Inc 1942 Sail on to Ceylon Herman Paley Edward Madden Starmer Jerome R. Remick & Co. 1916 Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay Egbert Van Alstyne Gus Kahn Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1917 Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay Egbert Van Alstyne Gus Kahn Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1917 Sailing Down the Chesapeake Bay George Botsford Jean C. Havez Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1913 Sailing Home Walter G. Samuels Walter G. Samuels IM Merman Words and Music Inc. 1937 Saint Louis Blues W.C. Handy W.C. Handy NA Tivick Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc. 1914 Includes ukulele arrangement Saint Louis Blues W.C. Handy W.C. Handy Barbelle Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc. 1942 Sakes Alive (March and Two-Step) Stephen Howard G.L. Lansing M. Witmark & Sons 1903 Banjo solo Sally in our Alley Henry Carey Henry Carey Starmer Armstronf Music Publishing Co. 1902 Sally Lou Hugo Frey Hugo Frey Robbins-Engel Inc. 1924 De Sylva Brown and Henderson Sally of My Dreams William Kernell William Kernell Joseph M. Weiss Inc. 1928 Sally Won't You Come Back? Dave Stamper Gene Buck Harms Inc. -

African American Sheet Music Collection, Circa 1880-1960

African American sheet music collection, circa 1880-1960 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Title: African American sheet music collection, circa 1880-1960 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1028 Extent: 6.5 linear feet (13 boxes) and 2 oversized papers boxes (OP) Abstract: Collection of sheet music related to African American history and culture. The majority of items in the collection were performed, composed, or published by African Americans. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Printed or manuscript music in this collection that is still under copyright protection and is not in the Public Domain may not be photocopied or photographed. Researchers must provide written authorization from the copyright holder to request copies of these materials. The use of personal cameras is prohibited. Source Collected from various sources, 2005. Custodial History Some materials in this collection originally received as part of the Delilah Jackson papers. Citation [after identification of item(s)], African American sheet music collection, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Elizabeth Russey, October 13, 2006. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. African American sheet music collection, circa 1880-1960 Manuscript Collection No. 1028 This finding aid may include language that is offensive or harmful. -

215269798.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Appendix: Partial Filmographies for Lucile and Peggy Hamilton Adams

Appendix: Partial Filmographies for Lucile and Peggy Hamilton Adams The following is a list of films directly related to my research for this book. There is a more extensive list for Lucile in Randy Bryan Bigham, Lucile: Her Life by Design (San Francisco and Dallas: MacEvie Press Group, 2012). Lucile, Lady Duff Gordon The American Princess (Kalem, 1913, dir. Marshall Neilan) Our Mutual Girl (Mutual, 1914) serial, visit to Lucile’s dress shop in two episodes The Perils of Pauline (Pathé, 1914, dir. Louis Gasnier), serial The Theft of the Crown Jewels (Kalem, 1914) The High Road (Rolfe Photoplays, 1915, dir. John Noble) The Spendthrift (George Kleine, 1915, dir. Walter Edwin), one scene shot in Lucile’s dress shop and her models Hebe White, Phyllis, and Dolores all appear Gloria’s Romance (George Klein, 1916, dir. Colin Campbell), serial The Misleading Lady (Essanay Film Mfg. Corp., 1916, dir. Arthur Berthelet) Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (Mary Pickford Film Corp., 1917, dir. Marshall Neilan) The Rise of Susan (World Film Corp., 1916, dir. S.E.V. Taylor), serial The Strange Case of Mary Page (Essanay Film Manufacturing Company, 1916, dir. J. Charles Haydon), serial The Whirl of Life (Cort Film Corporation, 1915, dir. Oliver D. Bailey) Martha’s Vindication (Fine Arts Film Company, 1916, dir. Chester M. Franklin, Sydney Franklin) The High Cost of Living (J.R. Bray Studios, 1916, dir. Ashley Miller) Patria (International Film Service Company, 1916–17, dir. Jacques Jaccard), dressed Irene Castle The Little American (Mary Pickford Company, 1917, dir. Cecil B. DeMille) Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (Mary Pickford Company, 1917, dir. -

![Jerome Kern Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5558/jerome-kern-collection-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-1215558.webp)

Jerome Kern Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered

Jerome Kern Collection Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2005 Revised 2010 March Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu002004 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/95702650 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Collection Summary Title: Jerome Kern Collection Span Dates: 1905-1945 Call No.: ML31.K4 Creator: Kern, Jerome, 1885-1945 Extent: circa 7,450 items ; 102 boxes ; 45 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: The collection consists primarily of Kern's show music, some holograph sketches; most are manuscript full and vocal scores of Kern's orchestrators and arrangers, especially Frank Saddler and Robert Russell Bennett. Film and other music also is represented, as well as a small amount of correspondence. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Bennett, Robert Russell, 1894-1981. Kern, Jerome, 1885-1945--Correspondence. Kern, Jerome, 1885-1945. Kern, Jerome, 1885-1945. Kern, Jerome, 1885-1945. Selections. Saddler, Frank. Subjects Composers--United States--Correspondence. Musical sketches. Musicals--Scores. Musicals--Vocal scores with piano. Titles Kern collection, 1905-1945 Administrative Information Provenance The bulk of the material, discovered in a Warner Bros. -

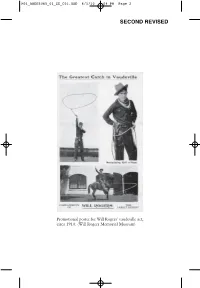

Second Revised

M01_ANDE5065_01_SE_C01.QXD 6/1/10 4:04 PM Page 2 SECOND REVISED Promotional poster for Will Rogers’ vaudeville act, circa 1910. (Will Rogers Memorial Museum) M01_ANDE5065_01_SE_C01.QXD 6/1/10 4:04 PM Page 3 SECOND REVISED CHAPTER 1 Will Rogers, the Opening Act One April morning in 1905, the New York Morning Telegraph’s entertainment section applauded a new vaudeville act that had appeared the previous evening at Madison Square Garden. The performer was Will Rogers, “a full blood Cherokee Indian and Carlisle graduate,” who proved equal to his title of “lariat expert.” Just two days before, Rogers had performed at the White House in front of President Theodore Roosevelt’s children, and theater-goers anticipated his arrival in New York. The “Wild West” remained an enigmatic part of the world to most eastern, urban Americans, and Rogers was from what he called “Injun Territory.” Will’s act met expectations. He whirled his lassoes two at a time, jumping in and out of them, and ended with his famous finale, extending his two looped las- soes to encompass a rider and horse that appeared on stage. While the Morning Telegraph may have stretched the truth— Rogers was neither full-blooded nor a graduate of the famous American Indian school, Carlisle—the paper did sense the impor- tance of this emerging star. The reviewer especially appreciated Rogers’ homespun “plainsmen talk,” which consisted of colorful comments and jokes that he intermixed with each rope trick. Rogers’ dialogue revealed a quaint friendliness and bashful smile that soon won over crowds as did his skill with a rope. -

Will Rogers on Slogans, Syndicated Column, April 1925

BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION * HE WENTIES T T WILL ROGERS on SLOGANS Syndicated column, April 12, 1925 Everything nowadays is a Saying or Slogan. You can’t go to bed, you can’t get up, you can’t brush your Teeth without doing it to some Advertising Slogan. We are even born nowadays by a Slogan: “Better Parents have Better Babies.” Our Children are raised by a Slogan: “Feed your Baby Cowlicks Malted Milk and he will be another Dempsey.” Everything is a Slogan and of all the Bunk things in America the Slogan is the Champ. There never was one that lived up to its name. They can’t manufacture a new Article until they have a Slogan to go with it. You can’t form a new Club unless it has a catchy Slogan. The merits of the thing has nothing to do with it. It is, just how good is the Slogan? Jack Dempsey: boxing Even the government is in on it. The Navy has a Slogan: “Join the Navy champion and celebrity of the 1920s and see the World.” You join, and all you see for the first 4 years is a Bucket of Soap Suds and a Mop, and some Brass polish. You spend the first 5 years in Newport News: Virginia city with major naval base Newport News. On the sixth year you are allowed to go on a cruise to Old Point Comfort. So there is a Slogan gone wrong. Old Point Comfort: resort near Newport News Congress even has Slogans: “Why sleep at home when you can sleep in Congress?” “Be a Politicianno training necessary.” “It is easier to fool ’em in Washington that it is at home, So why not be a Senator.” “Come to Washington and vote to raise your own pay.” “Get in the Cabinet; you won’t have to stay long.” “Work for Uncle Sam, it’s just like a Pension.” “Be a Republican and sooner or later you will be a Postmaster.” “Join the Senate and investigate something.” “If you are a Lawyer and have never worked for a Trust we can get you into the Cabinet.” All such Slogans are held up to the youth of this Country. -

Will Rogers: Native American Cowboy, Philosopher, and Presidential

UNIVERSIDAD DE CUENCA Escuela de Lengua y Literatura Inglesa ABSTRACT This senior thesis, “Will Rogers: Native American Cowboy, Philosopher, and Presidential Advisor,” presents the story of Will Rogers, indicating especially the different facets of his life that contributed to his becoming a legend and a tribute to the American culture. Will Rogers is known mostly as one of the greatest American humorist of his time and, in fact, of all times. This work focuses on the specific events and experiences that drove him to break into show business, Hollywood, and the Press. It also focuses on the philosophy of Will Rogers as well as his best known sayings and oft-repeated quotations. His philosophy, his wit, and his mirth made him an important and influential part of everyday life in the society of the United States in his day and for years thereafter. This project is presented in four parts. First, I discuss Rogers’ childhood and his life as a child-cowboy. Second, I detail how he became a show business star and a popular actor. Third, I recall his famous quotations and one-liners that are well known nowadays. Finally, there is a complete description of the honors and tributes that he received, and the places that bear Will Rogers name. Reading, writing, and talking about Will Rogers, the author of the phrase “I never met a man I didn’t like,” is to tell about a life-story of “completeness and self-revelation,” because he was a great spirit, a great writer, and a great human being. CONTENTS TABLE CHAPTER I: Biography of Will Rogers……………………………............