The Dynastic Impulse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Winter Newsletter

HHHHHHH LEGACY JOHN F. KENNEDY LIBRARY FOUNDATION Winter | 2013 Freedom 7 Splashes Down at JFK Presidential Library and Museum “I believe this nation should commit itself, to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” – President Kennedy, May 25, 1961 he John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum Joined on September 12 by three students from Pinkerton opened a special new installation featuring Freedom 7, Academy, the alma mater of astronaut Alan B. Shepard Jr., Tthe iconic space capsule that U.S. Navy Commander Kennedy Library Director Tom Putnam unveiled Freedom 7, Alan B. Shepard Jr. piloted on the first American-manned stating, “In bringing the Freedom 7 space capsule to our spaceflight. Celebrating American ingenuity and determination, Museum, the Kennedy Library hopes to inspire a new the new exhibit opened on September 12, the 50th anniversary generation of Americans to use science and technology of President Kennedy’s speech at Rice University, where he so for the betterment of our humankind.” eloquently championed America’s manned space efforts: Freedom 7 had been on display at the U.S. Naval “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the Academy in Annapolis, MD since 1998, on loan from the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. At the request of hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure Caroline Kennedy, Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus, the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is the U.S. -

380 Dorchester Ave

SouthBostonTODAYOnline • On Your Mobile • At Your Door September 3, 2020: Vol.8 Issue 35 SERVING SOUTH BOSTONIANS AROUND THE GLOBE Lynch, WWW.SOUTHBOSTONTODAY.COM Go to our South Boston Today page to view us online. Collins and Make sure you like & share with Biele Cruise your favorite social media! t to Victory Bos on T h o ith the backdrop of Covid t d u a o 19, Mail-In Voting and In- y Wcumbents being challenged S by liberal progressives (so-called), local elected officials Congressman @SBostonToday Stephen Lynch, Senator Nick Col- lins and Representative David Biele proved that constituent service is a key Want to see your ad in South element of re-election success. Each Boston Today & SBT Online? of them has a reputation for engaging with their constituents, which in the Office: 617.268.4032 or case of Lynch and Collins extends cell: 617.840.1355 or email at beyond the South Boston borders. [email protected] There were a couple of upsets in the @SBostonToday CONTINUED ON page 6 “THERE IS 380 Dorchester ave. SUBSTITUENO FOR HARD WORK” South boston,ma 02127617-752-4771 thespotclothing.com HAPPY LABOR DAY 2 SOUTHBOSTONTODAY • www.southbostontoday.com September 3, 2020 EDITORIAL NOW They Want The Riots Stopped And We All Know Why t would be difficult would have used all the and even months in some probably won’t, they are to make it any more resources at their disposal locations. In desperation, in a panic. They are mak- I obvious. All of a sud- plus the federal resources they are trying to shift the ing statements in an effort den last week, the gover- offered to them to stop it. -

New Exhibit Explores John F. Kennedy's Early Life

ISSUE 20 H WINTER 2016 THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND PUBLIC PROGRAMS AT THE JOHN F. KENNEDY PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM New Exhibit Explores John F. Kennedy’s Early Life efore he was president, John F. Kennedy was known simply as “Jack” to his friends and family. Young Jack, a new permanent exhibit at the BJohn F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, features documents, photographs, and objects that provide an intimate look at his childhood and family life, intellectual development, foreign travels, and military service. Through engagement with these primary sources, students may explore how a somewhat Senator John F. Kennedy signs a copy of Profiles rebellious, fun-loving and academically under-achieving teenager took a serious in Courage for a young fan, ca.1956–1957. interest in international affairs and started on the path of leadership that would Profiles in Courage one day lead to the White House. Turns 60! School Years In 1954, John F. Kennedy took a A wooden desk from Choate, the private boarding school he attended from leave of absence from the Senate 1931-35, evokes the time Jack spent there as a spirited high school student to undergo back surgery. During struggling to keep his grades up. Accompanying the desk are revealing excerpts his recuperation, he set to work researching and writing the stories from correspondence between Jack and his father, along with this quote from of US senators whom he considered a report by his housemaster: to have shown great courage under “Jack studies at the last minute, keeps appointments late, has little enormous pressure from their parties and their constituents: John Quincy sense of material value, and can seldom locate his possessions.” Adams, Daniel Webster, Thomas Hart Young people who are experiencing their own challenges, Benton, Sam Houston, Edmund G. -

Congressional Record on Choice

2019 Congressional Record on Choice Government Relations Department 1725 I Street, NW Suite 900 Washington, DC 20006 202.973.3000 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD ON CHOICE 116TH CONGRESS, 1ST SESSION NARAL Pro-Choice America’s 2019 Congressional Record on Choice documents the key House and Senate votes on reproduc- For over 50 years, NARAL Pro-Choice tive freedom taken during the first session of the 116th Congress. The 116th Congress reflects a wave of historic firsts—most America has led the fight for repro- significantly the first pro-choice majority in the House of Representatives. There are a record number of women serving ductive freedom for everyone, includ- in the House, and more LGBTQ people serving in Congress than ever before. The freshman class is also younger than most ing the right to access abortion. recent incoming classes and the 116th Congress reflects record breaking racial, ethnic, and religious diversity. Nowhere was the new pro-choice House majority more NARAL Pro-Choice America is powered evident than in the appropriations process. House spending bills for fiscal year 2020 reflected increased funding for vital by our 2.5 million members—in every family planning programs, defunded harmful abstinence-on- ly-until-marriage programs, and blocked many of the Trump administration’s efforts to use the regulatory process to state and congressional district. restrict access to abortion and family planning services. Though the House bills were not passed by the Senate, we We represent the more than 7 in 10 now see what can happen when lawmakers committed to reproductive rights are in control. -

Politicians and Their Professors the Discrepancy Between Climate Science and Climate Policy

Better Future Project 30 Bow Street Cambridge, MA. 02138 Politicians and Their Professors The Discrepancy between Climate Science and Climate Policy By Craig S. Altemose and Hayley Browdy Massachusetts Edition Better Future Project 1 Politicians and Their Professors: The Discrepancy between Climate Science and Climate Policy By Craig Altemose and Hayley Browdy With research and editing assistance provided by Elana Sulakshana, Alli Welton, and Kristen Wraith © 2012, Better Future Project 30 Bow Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 About This Report This report seeks to highlight the discrepancy between the overwhelming consensus on climate change that exists among the nation’s scientific community and the lack of action by federal leaders. Past studies have shown that 97-98% of climate scientists who publish in peer-reviewed journals agree with the consensus that climate change is real, happening now, and man-made. Since many politicians seem to disregard the views of such scientific “elites” as a whole, we decided to compare politicians’ views on climate change to those of the climate experts at their alma maters. These politicians clearly valued the expertise of the academics at their schools enough that they chose to (usually) spend tens of thousands of dollars and up to four years of their lives absorbing knowledge from these institutions’ experts. We thought that even if these politicians choose to disregard the consensus of national experts, they might be persuaded by the consensus of the higher education institutions in which they trusted enough to invest great amounts of their time and money. This report and the research supporting it are available online at www.betterfutureproject.org/resources. -

Sir Isaiah Berlin, Oral History Interview – 4/12/1965 Administrative Information

Sir Isaiah Berlin, Oral History Interview – 4/12/1965 Administrative Information Creator: Sir Isaiah Berlin Interviewer: Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. Date of Interview: April 12, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 23 pages Biographical Note Berlin, a professor of social and political theory at Oxford University from 1957 to 1967, discusses conversations he had with John F. Kennedy (JFK) about political theory and Russian politics, and compares JFK to other political leaders throughout history, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed June 29, 1971, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

The-Counter Hearing Aid

By Lise Hamlin The Hearing Loss Association of America has embarked on a campaign to support new legislation that, if passed, will change the face of hearing health care in America. And you can be part of it. On March 21, U.S. Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), Maggie Hassan (D-N.H.), and Johnny Isakson (R-Ga.), reintroduced legislation (Senate bill S. 670) to make hearing aids for those with mild to moderate hearing loss available over the counter (OTC). Senators Warren and Grassley first introduced the bill last December and have now reintroduced it for 2017. A companion bill (H.R. 1652), led by Representatives Joe Kennedy III (D-Mass.) and Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.), was also introduced in the House. Co-sponsors of the House bill (at press time) include Representatives Don Bacon (R-Neb.), Earl “Buddy” Carter (R-Ga.), Eleanor Holmes-Norton (D-DC), James P. McGovern (D-Mass.), and Niki Tsongas (D-Mass.). The Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act of 2017 would require the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to create a new category of over-the-counter hearing aids and remove unnecessary barriers to getting hearing aids. We need your help in support-ing Senators Warren and Grassley to get this groundbreaking piece of legislation passed! If the “Warren-Grassley bill” is enacted, the immediate benefit will of course © Cindy Dyer Cindy © be for those whom these new devices are intended—people with mild to moderate hearing loss who might otherwise be unable to purchase that first hearing aid because it’s too expensive or because the process is so confusing. -

David F. Powers Oral History Interview – RFK#1, 04/03/69 Administrative Information

David F. Powers Oral History Interview – RFK#1, 04/03/69 Administrative Information Creator: David F. Powers Interviewer: Larry J. Hackman Date of Interview: April 3, 1969 Place of Interview: Waltham, Massachusetts Length: 22 pages Biographical Note Kennedy friend and associate; Special Assistant to the President (1961-1963). In this interview, Powers discusses Robert F. Kennedy’s involvement in John F. Kennedy’s (JFK) campaigns for senate and president and the aftermath of JFK’s assassination, among other issues. Access Open Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed June 22, 1989, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

CPF ID Full Name Reverse Receipt Total Expenditure Total

CPF_ID Full_Name_Reverse Receipt_Total Expenditure_Total 80769 1199 SEIU MA PAC $ 751,545.68 $ 428,576.84 80479 MA & Northern NE Laborers' District Council Pol Action Comm $ 595,238.86 $ 288,586.08 80153 Retired Public Employees PAC $ 349,568.69 $ 285,399.17 80826 Committee for a Democratic House Political Action Committee $ 217,837.30 $ 215,066.64 80221 International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Local 103 Pol Action Comm $ 170,192.30 $ 151,869.21 80229 Pipefitters Local #537 Pol Action Comm $ 89,668.65 $ 121,304.73 80220 Chapter 25 Associated the Nat'l DRIVE PAC of the Int'l Brotherhood of Teamsters $ 69,593.09 $ 109,840.99 80096 Massachusetts Dental Society Political Action Committee $ 45,606.66 $ 92,764.01 80219 Ironworkers Union Local 7 Pol Action Comm $ 130,281.95 $ 92,094.05 80530 Int'l Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local Union 2222 Pol Action Comm $ 84,602.91 $ 72,795.90 80112 MA Assoc. of Realtors Pol Action Comm. - MA RPAC $ 96,661.15 $ 69,803.81 80144 Painters District Council #35 PAC $ 117,615.07 $ 59,220.92 80374 Professional Fire Fighters of MA People's Cttee $ 82,165.96 $ 57,315.79 80194 Sheet Metal Workers Local Union 17 People's Ctte $ 45,591.19 $ 48,884.00 80227 American Federation of Teachers MA PAC $ 37,247.31 $ 43,000.00 80323 Massachusetts Brick Layers People's Committee $ 39,408.13 $ 42,410.00 80325 Committee for a Democratic Senate Pol Action Comm. $ 82,885.71 $ 33,014.11 80577 Boston Carmen's Union PAC $ 15,483.50 $ 32,700.00 80690 MA Correction Officers Federated Union PAC M.C.O.F.U PAC $ 36,226.61 $ 30,850.00 80224 Local 509 Service Employees Int'l Union Comm on Pol Ed, MA Workers' Pol Action Comm. -

GUIDE to the 117Th CONGRESS

GUIDE TO THE 117th CONGRESS Table of Contents Health Professionals Serving in the 117th Congress ................................................................ 2 Congressional Schedule ......................................................................................................... 3 Office of Personnel Management (OPM) 2021 Federal Holidays ............................................. 4 Senate Balance of Power ....................................................................................................... 5 Senate Leadership ................................................................................................................. 6 Senate Committee Leadership ............................................................................................... 7 Senate Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................. 8 House Balance of Power ...................................................................................................... 11 House Committee Leadership .............................................................................................. 12 House Leadership ................................................................................................................ 13 House Health-Related Committee Rosters ............................................................................ 14 Caucus Leadership and Membership .................................................................................... 18 New Members of the 117th -

SARGENT SHRIVER's LIFE AS an ENGAGED CATHOLIC and AS an ACTIVE LIBERAL Dissertation Submitted to T

INSTITUTIONAL INNOVATOR: SARGENT SHRIVER’S LIFE AS AN ENGAGED CATHOLIC AND AS AN ACTIVE LIBERAL Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Daniel E. Martin UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio May 2016 INSTITUTIONAL INNOVATOR: SARGENT SHRIVER’S LIFE AS AN ENGAGED CATHOLIC AND AS AN ACTIVE LIBERAL Name: Martin, Daniel E. APPROVED BY: ______________________________________ Anthony B. Smith, Ph.D. Committee Chair ______________________________________ Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________________ Cecilia A. Moore, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________________ David J. O’Brien, Ph.D. Committee Member ii ABSTRACT INSTITUTIONAL INNOVATOR: SARGENT SHRIVER’S LIFE AS AN ENGAGED CATHOLIC AND AS AN ACTIVE LIBERAL Name: Martin, Daniel Edwin University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Anthony B. Smith This dissertation argues that Robert Sargent Shriver, Jr.’s Roman Catholicism is undervalued when understanding his role crafting late 1950s and 1960s public policies. Shriver played a role in desegregating Chicago’s Catholic and public school systems as well as Catholic hospitals. He helped to shape and lead the Peace Corps. He also designed many of the programs launched in President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Shriver’s ability to produce new policies and agencies within a broader structure of governance is well known. However, Shriver’s Catholicism is often neglected when examining his influence on key public policy initiatives and innovations. This dissertation argues that Shriver’s Roman Catholic upbringing formed him in such a way as to understand the nature of large bureaucracies and to see possibilities for innovation within an overarching structure. -

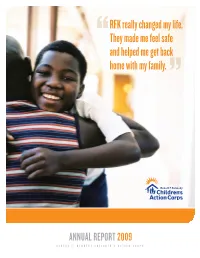

RFK Really Changed My Life. They Made Me Feel Safe and Helped Me Get Back Home with My Family

RFK really changed my life. They made me feel safe and helped me get back home with my family. ANNUAL REPORT 2009 ROBERT F. KENNEDY CHILDREN’S ACTION CORPS ROBERT F. KENNEDY CHILDREN’S ACTION CORPS Senator Edward M. Kennedy In 2009, we mourned together over the loss of Senator Edward M. Kennedy, one of the most passionate and articulate advocates for children, health and social justice. At our 2006 Embracing the Legacy event, he quoted from the words of Nobel Laureate Gabriela Mistral, telling us, “We are guilty of many errors and many faults, but our worst crime is abandoning the children, neglecting the fountain of life. Many of the things we need can wait. The child cannot. To him we cannot answer “Tomorrow.” His name is “Today.” “There has been no more faithful champion of the poor, of working families, of all those who depend on essential government services and the positive role that the government can and should play, than Senator Edward Kennedy.” ~ Ed McElroy, American Federation of Teachers Convention, Boston July 21, 2006 “For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives and the dream shall never die.” “There is a new wave of change all around us, and if we set our President Obama has described his compass true, we will reach our breathtaking span of accomplishment: destination” “For five decades, virtually every major piece of legislation to advance the civil rights, health, and economic well being of the American people bore his name and resulted from his efforts.” “He has proven himself, time and again, to be a fighter for children and educators,” said Reg Weaver, the immediate past President of the National Education Association.