SARGENT SHRIVER's LIFE AS an ENGAGED CATHOLIC and AS an ACTIVE LIBERAL Dissertation Submitted to T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Anthropology Through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-Based Sentiment

Cultural Anthropology through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-based Sentiment Peter A. Gloor, Joao Marcos, Patrick M. de Boer, Hauke Fuehres, Wei Lo, Keiichi Nemoto [email protected] MIT Center for Collective Intelligence Abstract In this paper we study the differences in historical World View between Western and Eastern cultures, represented through the English, the Chinese, Japanese, and German Wikipedia. In particular, we analyze the historical networks of the World’s leaders since the beginning of written history, comparing them in the different Wikipedias and assessing cultural chauvinism. We also identify the most influential female leaders of all times in the English, German, Spanish, and Portuguese Wikipedia. As an additional lens into the soul of a culture we compare top terms, sentiment, emotionality, and complexity of the English, Portuguese, Spanish, and German Wikinews. 1 Introduction Over the last ten years the Web has become a mirror of the real world (Gloor et al. 2009). More recently, the Web has also begun to influence the real world: Societal events such as the Arab spring and the Chilean student unrest have drawn a large part of their impetus from the Internet and online social networks. In the meantime, Wikipedia has become one of the top ten Web sites1, occasionally beating daily newspapers in the actuality of most recent news. Be it the resignation of German national soccer team captain Philipp Lahm, or the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight 17 in the Ukraine by a guided missile, the corresponding Wikipedia page is updated as soon as the actual event happened (Becker 2012. -

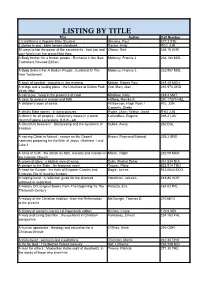

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

Siete Lenguas: the Rhetorical History of Dolores Huerta and the Rise of Chicana Rhetoric Christine Beagle

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository English Language and Literature ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2016 Siete Lenguas: The Rhetorical History of Dolores Huerta and the Rise of Chicana Rhetoric Christine Beagle Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds Recommended Citation Beagle, Christine. "Siete Lenguas: The Rhetorical History of Dolores Huerta and the Rise of Chicana Rhetoric." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/engl_etds/34 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Language and Literature ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Garcia i Christine Beagle Candidate English, Rhetoric and Writing Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Michelle Hall Kells, Chairperson Irene Vasquez Natasha Jones Melina Vizcaino-Aleman Garcia ii SIETE LENGUAS: THE RHETORICAL HISTORY OF DOLORES HUERTA AND THE RISE OF CHICANA RHETORIC by CHRISTINE BEAGLE B.A., English Language and Literature, Angelo State University, 2005 M.A., English Language and Literature, Angelo State University, 2008 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ENGLISH The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico November 10, 2015 Garcia iii DEDICATION To my children Brandon, Aliyah, and Eric. Your brave and resilient love is my savior. I love you all. Garcia iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, to my dissertation committee Michelle Hall Kells, Irene Vasquez, Natasha Jones, and Melina Vizcaino-Aleman for the inspiration and guidance in helping this dissertation project come to fruition. -

Margaret (Peggy) Roach Papers, 1945-2001, N.D

Women and Leadership Archives Loyola University Chicago Margaret (Peggy) Roach Papers, 1945-2001, n.d. Creator: Roach, Margaret (Peggy), (1927-2006) Extent: 12 linear ft. Location: Processor: Dorothy Hollahan B.V.M., January 17, 2003. Updated by Elizabeth A. Myers, 2007. Updated by Catherine Crosse, 2011. Administration Information Access Restrictions: None Usage Restrictions: Copyright of materials created by Margaret Roach was transferred to WLA Oct. 1 2001. Preferred Citation: Loyola University of Chicago. Women and Leadership Archives. Margaret Roach Papers, 1945-2001. Box #. Folder #. Provenance: Margaret Roach donated this collection to the Women and Leadership Archives of the Ann Ida Gannon B.V.M. Center for Women and Leadership on October 1, 2001 (WLA2001.24) and January 22, 2002 (WLA2002.03). Separations: 3 linear feet of duplicate material. See Also: Women and Leadership Archives-Mundelein Alumnae Files: “Margaret Roach” An Alley in Chicago –The Life and Legacy of Monsignor John J. Egan -Commemorative Edition, by Marjorie Frisbie with an introduction and conclusion by Robert A. Ludwig. Originally published in 1991, the book was reprinted in 2002. See also the University of Notre Dame Archives—Monsignor John J. Egan. Biography Margaret (Peggy) Roach was born on the north side of Chicago, Illinois on May 16, 1927 to James E. and Cecile Duffy Roach. Peggy once told a Chicago Sun Times reporter that she was known as Margaret only to the Social Security Administration. Peggy had three sisters and one brother and has always been a strong family person. Graduating from St. Scholastica High School in 1945 Peggy registered at Mundelein College where she graduated in 1949. -

Villa Tevere: Origen Y Primera Historia De La Sede Central Del Opus

Orígenes y primera historia de Villa Tevere. Los edificios de la sede central del Opus Dei en Roma (1947-1960) AlFREDO MÉNDIZ Abstract: La sede central del Opus Dei, Villa Tevere, situada en la zona norte de Roma, fue adquirida en 1947 . Su dueño anterior, Mario Gori Mazzoleni, había construido el edificio principal de la finca entre 1928 y 1931 y lo había alquilado en 1936 a la Legación de Hungría ante la Santa Sede . La plena ocupación del inmueble solo fue posible tras dos años de negociaciones ‒no siempre distendidas‒ con la burocracia del nuevo estado húngaro nacido de la guerra, que deseaba seguir usándolo . En 1949 comenzaron los trabajos de adaptación de la finca, paralelos a la urbanización de esa zona de Roma y a la primera expansión internacional del Opus Dei . Keywords: Opus Dei −Villa Tevere −Villa Sacchetti − Mario Gori Mazzoleni − Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer − Álvaro del Portillo − Fernando Delapuente − Jesús Álvarez Gazapo − Roma − Hungría − 1947-1960 The Origins and the Early History of Villa Tevere . The buildings of the central house of Opus Dei in Rome (1947-1960): The central house of Opus Dei, known as Villa Tevere and situated then in the northern area of Rome, was acquired in 1947 . Its previous owner, Mario Gori Mazzoleni, had con- structed the principal building on the site between 1928 and 1931, and had rented it out in 1936 to the Legation of Hungary to the Holy See . Full occupa- tion of the premises was to be possible only after two years of negotiations – by no means always easy – with officials of the new Hungarian State born out of World War II who sought to continue using it . -

YVES CONGAR's THEOLOGY of LAITY and MINISTRIES and ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION in the UNITED STATES Dissertation Submitted to Th

YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Alan D. Mostrom UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2018 YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Name: Mostrom, Alan D. APPROVED BY: ___________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor ___________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ Timothy R. Gabrielli, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader, Seton Hill University ___________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ William H. Johnston, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Alan D. Mostrom All rights reserved 2018 iii ABSTRACT YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Name: Mostrom, Alan D. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. Yves Congar’s theology of the laity and ministries is unified on the basis of his adaptation of Christ’s triplex munera to the laity and his specification of ministry as one aspect of the laity’s participation in Christ’s triplex munera. The seminal insight of Congar’s adaptation of the triplex munera is illumined by situating his work within his historical and ecclesiological context. The U.S. reception of Congar’s work on the laity and ministries, however, evinces that Congar’s principle insight has received a mixed reception by Catholic theologians in the United States due to their own historical context as well as their specific constructive theological concerns over the laity’s secularity, or the priority given to lay ministry over the notion of a laity. -

The World Peace: the Legacy of Edmund S. Muskie

Cornell International Law Journal Volume 30 Article 1 Issue 3 Symposium 1997 The orW ld Peace: The Legacy of Edmund S. Muskie George J. Mitchell Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mitchell, George J. (1997) "The orldW Peace: The Legacy of Edmund S. Muskie," Cornell International Law Journal: Vol. 30: Iss. 3, Article 1. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol30/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell International Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. World Peace: The Legacy of Edmund S. Muskie George J. Mitchell* When Ed Muskie's parents came to the United States, they left the Polish province of the Imperial Russian Empire. Their son served with millions of other Americans in World War II, a war which began with the Nazi onslaught against his ancestral homeland and ended with a partially resurrected Poland. A few weeks before Ed Muskie ended thirty-five years in public office as more than thirty Soviet armored divisions massed on Poland's borders, he found himself meeting his NATO counterparts in Brussels to issue joint warnings to the Soviet Union. In December 1980, it was an open question if the Soviets would invade. The Soviets did not invade, though no one at that time could have predicted the outcome of that chapter of the Cold War with certainty. -

Curriculum Vitae CAROLYN J

Curriculum Vitae CAROLYN J. TUCKER HALPERN Department of Maternal and Child Health Office: (919) 966-5981 (MCH) 401 Rosenau, CB 7445 University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill email: [email protected] Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7445 Education PhD 1982 Developmental Psychology, University of Houston–Central Campus, Houston, TX. MA 1979 Developmental Psychology, University of Houston–Central Campus, Houston, TX. BS 1976 Psychology, University of Houston–Central Campus, Houston, TX. (Summa cum laude with University and Departmental Honors) Professional Experience 2017- present Faculty Fellow, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. 2015 - present Chair, Department of Maternal and Child Health, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. 2014 – 2015 Interim Chair, Department of Maternal and Child Health, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. 2013 – 2014 Vice-Chair, Department of Maternal and Child Health, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. 2011 – present Professor with Tenure, Department of Maternal and Child Health, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. 2004 - 2011 Associate Professor with Tenure, Department of Maternal and Child Health, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. 2000 - 2019 Faculty Fellow, Center for Developmental Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. 1998 - present Faculty Fellow, Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. -

Founding Documents of the Peace Corps. the Constitution Community: Postwar United States (1945 to Early 1970S)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 462 356 SO 033 607 AUTHOR Schur, Joan Brodsky TITLE Founding Documents of the Peace Corps. The Constitution Community: Postwar United States (1945 to Early 1970s). INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 16p.; Photographic images may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROM National Archives and Records Administration, 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Washington, DC 20408. Tel: 866-325-7208 (Toll Free); e-mail: [email protected]. For full text: http://www.nara.gov/education/cc/main.html. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Citizen Participation; *Presidents of the United States; *Primary Sources; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Teacher Developed Materials; *United States History; *Volunteers IDENTIFIERS Congress; *Kennedy (John F); National Civics and Government Standards; National History Standards; *Peace Corps ABSTRACT The origins of the idea for the Peace Corps are numerous and occurred well before the Kennedy era, but the founding of the Peace Corps is one of President John Kennedy's most enduring legacies. Since the Peace Corps founding in 1961 more than 150,000 citizens of all ages and backgrounds have worked in more than 130 countries throughout the world as volunteers in such fields as health, teaching, agriculture, urban planning, skilled trades, forestry, sanitation, and technology. To allay fears that the Peace Corps would harbor secret agendas or become a tool of the CIA, volunteers are sent only -

Picking the Vice President

Picking the Vice President Elaine C. Kamarck Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. Contents Introduction 4 1 The Balancing Model 6 The Vice Presidency as an “Arranged Marriage” 2 Breaking the Mold 14 From Arranged Marriages to Love Matches 3 The Partnership Model in Action 20 Al Gore Dick Cheney Joe Biden 4 Conclusion 33 Copyright 36 Introduction Throughout history, the vice president has been a pretty forlorn character, not unlike the fictional vice president Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays in the HBO seriesVEEP . In the first episode, Vice President Selina Meyer keeps asking her secretary whether the president has called. He hasn’t. She then walks into a U.S. senator’s office and asks of her old colleague, “What have I been missing here?” Without looking up from her computer, the senator responds, “Power.” Until recently, vice presidents were not very interesting nor was the relationship between presidents and their vice presidents very consequential—and for good reason. Historically, vice presidents have been understudies, have often been disliked or even despised by the president they served, and have been used by political parties, derided by journalists, and ridiculed by the public. The job of vice president has been so peripheral that VPs themselves have even made fun of the office. That’s because from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the last decade of the twentieth century, most vice presidents were chosen to “balance” the ticket. The balance in question could be geographic—a northern presidential candidate like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts picked a southerner like Lyndon B. -

The President's Desk: a Resource Guide for Teachers, Grades 4

The President’s Desk A Resource Guide for Teachers: Grades 4-12 Department of Education and Public Programs With generous support from: Edward J. Hoff and Kathleen O’Connell, Shari E. Redstone John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum Table of Contents Overview of The President’s Desk Interactive Exhibit.... 2 Lesson Plans and Activities................................................................ 40 History of the HMS Resolute Desk............................................... 4 List of Lessons and Activities available on the Library’s Website... 41 The Road to the White House...................................................................... 44 .......................... 8 The President’s Desk Website Organization The President at Work.................................................................................... 53 The President’s Desk The President’s Desk Primary Sources.................................... 10 Sail the Victura Activity Sheet....................................................................... 58 A Resource Guide for Teachers: Grades 4-12 Telephone.................................................................................................... 11 Integrating Ole Miss....................................................................................... 60 White House Diary.................................................................................. 12 The 1960 Campaign: John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Scrimshaw.................................................................................................. -

CA-Congressional-Delegation-Letter

June 22, 2020 The Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker of the House U.S. House of Representatives H-232, U.S. Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515 The Honorable Kevin McCarthy Minority Leader U.S. House of Representatives H-204, U.S. Capitol Washington, D.C. 20515 The Honorable Dianne Feinstein U.S. Senator from California 331 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 The Honorable Kamala Harris U.S. Senator from California 112 Hart Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 RE: Include Urgently Needed Funding for Water Infrastructure and Water Affordability Needs in Next Congressional Response to COVID-19 Pandemic Dear Speaker Pelosi, Minority Leader McCarthy, Senators Feinstein and Harris, and Members of the California Congressional Delegation: Our organizations collectively represent both California frontline communities as well as over 500 California water agencies and other water and environmental stakeholders. In this time of crisis, we have come together to urge the California Congressional Delegation to include funding for urgent water infrastructure and water affordability needs as part of the next federal stimulus package or other pending Congressional actions. We urge your support for the water-related provisions of the HEROES Act. We also urge you to take the following steps as part of the next federal stimulus package or other pending water or infrastructure-related Congressional actions: 1. $100 billion in new funding over five years for Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds, with at least 20 percent of the new funding distributed to disadvantaged communities as additional subsidization (grants) rather than loans and eligibility for the new funding for all water systems, regardless of their organizational structure.