Chinese Tea in World History by MARC Jason Gilbert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

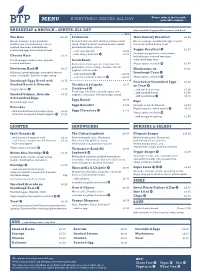

EVERYTHING SERVED ALL DAY Your Table Number

Please order at the bar with MENU EVERYTHING SERVED ALL DAY your table number... BREAKFAST & BRUNCH – SERVED ALL DAY Our scrambled egg includes tomato and basil NEW The Boss £10.95 Flatbreads West Country Breakfast £8.50 Bacon, sausage, hog’s pudding, Za’atar flatbread, date chutney, harissa, herb Bacon, sausage, scrambled egg, roasted mushrooms, roasted new potatoes, salad, Greek yoghurt, toasted sesame seeds, tomatoes, baked beans, toast roasted tomatoes, baked beans, pickled red onion, sumac Veggie Breakfast £8.25 scrambled egg, two rounds of toast ...with spiced lamb £9.50 ...with crispy halloumi £9.25 Roasted new potatoes, mushrooms, Chorizo Hash £8.75 baked beans, roasted tomatoes, Poached eggs, mushrooms, spinach, Grain Bowls scrambled egg, toast roasted tomatoes Buckwheat, black quinoa, avocado, lime Vegan option available £6.95 pickled beetroot, orange, harissa, Greek Sweetcorn Hash £8.75 £6.35 yoghurt, nuts & seeds Mushrooms on Halloumi, poached eggs, avocado & tomato Sourdough Toast ...with pork belly salsa, coriander, Tabasco maple syrup £10.95 ...with hot smoked mackerel £10.25 Vegan option available Sourdough Eggy Bread with £8.75 Poached or Scrambled Eggs £5.00 Smoked Bacon & Avocado Cheddar & Jalapeño £8.75 on Toast Veggie option £7.75 Cornbread ...add smoked salmon £2.60 Fried egg, smashed avocado, spicy salsa, ...add smoked bacon £2.50 Smoked Salmon, Avocado £8.75 yoghurt, coriander, Tabasco maple syrup ...add mushrooms £2.10 & Scrambled Eggs Eggs Royale £8.75 On sourdough toast Baps Eggs Benedict £7.95 Sausage or smoked -

The Demand Curve in the Boston Tea Party: When All Else Fails, Shift the Demand, Ye Patriots

Document Section 2 The Demand Curve in the Boston Tea Party: When all else fails, shift the Demand, ye Patriots. BACKGROUND: Students should have prior knowledge of the economic models describing supply and demand. Students should have working knowledge of shifting and movement along the demand and supply curves. Knowledge of marginal utility analysis is also assumed. Application of the theory of indifference curves in the creation of the demand curve could be helpful but not necessary for this exercise. GOAL: Students will apply their knowledge of supply and demand analysis to the events leading up to the Boston Tea Party. They will evaluate the effectiveness of their models in describing the consumer behavior of tea. CONCEPT REVIEW: Using regular demand/supply analysis, describe 1. What factors cause a shift in demand? 2. What factors cause a movement along the demand curve? DOCUMENT ANALYSIS: Read the following set of documents pertaining to the background of the Boston Tea Party. 1. On a separate piece of paper answer the “Consider” question that corresponds with each document. 2. Discuss your answers with your group and come to some consensus over the meaning of the documents. 3. GRAPH—Using your best demand/supply analysis, show how the Patriots were shaping and influencing the market for tea in the years leading up to the Boston Tea Party. TASK: Based on the documents and your knowledge of 18th century American history, do you think the Patriots were able to change demand for tea? Why or why not? Would you recommend it as sound policy to continue to try to change demand? If so, how would you go about it? If not, what might you do instead to keep up with the demand? Be able to provide a coherent explanation to your fellow Patriots. -

Review & Analysis

Chinese Social Sciences Today Review & Analysis THURSDAY APRIL 11 2019 5 However, most extant referen- Translation and research of tea classic tially valuable books and records about tea culture are aged. Some information is outdated and im- promoted Chinese tea culture to world practical in developed society. Thus when translating tea culture documents, including The Classic of Tea, Chinese and foreign trans- CULTURAL COMMUNICATION lators alike have depended largely By YUAN MENGYAO on foreignization and occasional and DONG XIAOBO domestication in their translation methodologies, in a bid to dissem- Tea is one of the main symbols of inate tea culture more efficiently. the Chinese culture. As early as in the Western Han Dynasty (202 Cultural blending BCE–8 CE), tea and tea culture The Classic of Tea and Chinese had been spread overseas. The tea culture have been influential Classic of Tea, also translated into overseas not only because they in- Cha Ching based on the Wade- tensified other countries’ interest Giles romanization system, not in studying Chinese tea and were only advanced the development of fused into their daily customs, tea culture in China, but also gen- but also because they profoundly erated extensive influence abroad. impacted the literature, art and Authored by Tang Dynasty tea aesthetic communities of other expert Lu Yu (733–804), who has nations. been honored as the Sage of Tea, After the introduction of The the masterpiece is the first known Classic of Tea to the West, a great monograph on tea in the world. number of tea culture mono- Studying the outbound transmis- Tang Dynasty tea expert Lu Yu (733–804) and part of his magnum opus The Classic of Tea Photo: FILE graphs that were modeled after sion of tea culture in ancient times the Chinese classic emerged, and along with the history of the trans- troduced into Japan in the South- leaves via land routes has had a liam Ukers compiled and pub- many countries tailored the tea lation of The Classic of Tea will ern Song Dynasty (1127–1279). -

GROUP TEA PARTY RESERVATION SIP Tea Room Policies & Agreement: 6-12 Guests

..r GROUP TEA PARTY RESERVATION SIP Tea Room Policies & Agreement: 6-12 guests Please find a list of all the very boring, yet very important, details below. We are grateful for your consideration and look forward to being a part of your special day. Terms & Conditions • Capacity: In order to accommodate all guests, we limit parties in the tea room to 12 guests. *We offer full private rental of the Tea Room for parties of 13-30, visit our website for full details on Private Tea Room Rentals. • Availability: Large party reservations begin at 11:00am, 1:00pm or 3:00pm. • Time Limits: Parties are reserved for 1 hour 45 minutes. Please note that the party must be completed by the agreed upon time. In order for us to properly clean and seat our next reservation, it is imperative that the space be vacated on time. In the event that guests stay over the allotted time, a fee may be charged. • Children (8 years and under). We have found that a max of 5 children is ideal for the tea room seating. Our facility is best suited for those ages 8 or older. We do not have space for large stroller’s. No highchairs available. • Space Usage: There is NOT room to open gifts, play games or give speeches in the tea room – consider a Private Tea Room Rental if you wish to have activities. • No Last-Minute Guests: Host must make sure that the number of guests does not over-exceed the guaranteed number. We do not “squeeze” in guests. -

Tea Drinking Culture in Russia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hosei University Repository Tea Drinking Culture in Russia 著者 Morinaga Takako 出版者 Institute of Comparative Economic Studies, Hosei University journal or Journal of International Economic Studies publication title volume 32 page range 57-74 year 2018-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10114/13901 Journal of International Economic Studies (2018), No.32, 57‒74 ©2018 The Institute of Comparative Economic Studies, Hosei University Tea Drinking Culture in Russia Takako Morinaga Ritsumeikan University Abstract This paper clarifies the multi-faceted adoption process of tea in Russia from the seventeenth till nineteenth century. Socio-cultural history of tea had not been well-studied field in the Soviet historiography, but in the recent years, some of historians work on this theme because of the diversification of subjects in the Russian historiography. The paper provides an overview of early encounters of tea in Russia in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, comparing with other beverages that were drunk at that time. The paper sheds light on the two supply routes of tea to Russia, one from Mongolia and China, and the other from Europe. Drinking of brick tea did not become a custom in the 18th century, but tea consumption had bloomed since 19th century, rapidly increasing the import of tea. The main part of the paper clarifies how Russian- Chines trade at Khakhta had been interrelated to the consumption of tea in Russia. Finally, the paper shows how the Russian tea culture formation followed a different path from that of the tea culture of Europe. -

A Russian Tea Wedding an Interview with Katya & Denis

Voices from the Hut A Russian Tea Wedding An Interview with Katya & Denis This growing community often blows our hearts wide open. It is the reason we feel so inspired to publish these magazines, build centers and host tea ceremonies: tea family! Connection between hearts is going to heal this world, one bowl at a time... Katya & Denis are tea family to us all, and so let’s share in the occasion and be distant witnesses at their beautiful tea wedding! 茶道 ne of the things we love the imagine this continuing in so many dinner, there was a party for the Bud- O most about Global Tea Hut is beautiful ways! dhists on the tour and Denis invited the growing community, and all the We very much want to foster Katya to share some puerh with him. beautiful family we’ve made through community here, and way beyond It was the first time she’d ever tried tea. As time passes, this aspect of be- just promoting our tea tradition. It such tea, and she loved it from the ing here, sharing tea with all of you, doesn’t matter if you practice tea in first sip. Then, in 2010, Katya moved starts to grow. New branches sprout our tradition or not, we’re family—in from her birthplace in Siberia, every week, and we hear about new our love for tea, Mother Earth and Komsomolsk-na-Amure, to Moscow and amazing ways that members are each other! If any of you have any to live with Denis (her hometown is connecting to each other. -

What Every Dentist Should Know About Tea

Nutrition What every dentist should know about tea Moshe M. Rechthand n Judith A. Porter, DDS, EdD, FICD n Nasir Bashirelahi, PhD Tea is one of the most frequently consumed beverages in the world, of drinking tea, as well as the potential negative aspects of tea second only to water. Repeated media coverage about the positive consumption. health benefits of tea has renewed interest in the beverage, particularly Received: August 23, 2013 among Americans. This article reviews the general and specific benefits Accepted: October 1, 2013 ea has been a staple of Chinese life for their original form.4 Epigallocatechin-3- known as reactive oxygen species (ROS) so long that it is considered to be 1 of galate (EGCG) is the principal bioactive are formed through normal aerobic cellular Tthe 7 necessities of Chinese culture.1 catechin left intact in green tea and the metabolism. During this process, oxygen is The popularity of tea should come as no one responsible for many of its health partially reduced to form a reactive radical surprise considering the recent studies benefits.3 By contrast, black tea is fully as a byproduct in the formation of water. conducted confirming tea’s remarkable oxidized/fermented during processing, ROS are helpful to the body because they health benefits.2,3 The drinking of tea dates which accounts for both its stronger flavor assist in the degradation of microbial back to the third millenium BCE, when and the fact that its catechin content is disease.5 However, ROS also contain free Shen Nong, the famous Chinese emperor lower than the other teas.2 Black tea’s fer- radical electrons that can wreak havoc on and herbalist, discovered the special brew. -

Auntie's Wok & Steam Menu

LUNCH TRAY SETS Monday - Friday 12:00pm - 2:30pm One main, one side and *Andaz Iced Tea $26 One main, one side, one dessert and *Andaz Iced Tea $29 MAINS SIDES Auntie’s Laksa, tiger prawns, sh cake, vermicelli rice noodles Crispy Organic Cucumber Beef Brisket Noodle Soup, chilli oil, spring onion Double Boiled Soup of the Day Hong Kong Style Vegetables Char Kway Teow, Chinese sausage, tiger prawns, squid, sh cake Wok-fried French Beans Kung Pao Chicken, cashew nuts, mixed peppers, organic jasmine rice Seafood Organic Fried Rice, tiger prawns, squid, crab meat, egg *OUR SPECIALTY Steamed Atlantic Cod, Hong Kong style, organic jasmine rice Andaz Iced Tea Sweet and Sour Pork Belly, mixed peppers, celery, organic jasmine rice A refreshing cup of TWG Singapore Breakfast tea blended with a homemade Wok-fried Angus Beef, homemade black pepper sauce, organic jasmine rice pandan syrup for local twist. DESSERTS WINES & BEERS $8 NETT Almond Silken Tofu & Lychee Jelly Chardonnay, Somerton, Australia Chilled Mango Sago & Pomelo Sauvignon Blanc, Los Vascos, Chile Steamed Yam Paste with Coconut Cream & Gingko Nut Prosecco, Veneto, Italy, N.V Seasonal Sliced Fruit Platter Shiraz, Somerton, Australia Cabernet Sauvignon, Los Vascos, Chile Andaz Pils, Pilsner, Singapore COFFEE & TEA $6 Rainforest Alliance Coffee Heineken 0.0, Lager, Netherlands Americano, Cappuccino Tiger, Lager, Singapore Double Espresso, Espresso, Latte TWG Teas Earl Grey, English Breakfast, Sencha Singapore Breakfast, Moroccan Mint Tag @AndazSingapore to share your best dining experience -

Teahouses and the Tea Art: a Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie Master's Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 – 60 Credits – Autumn 2015) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO 24 November, 2015 © LI Jie 2015 Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie http://www.duo.uio.no Print: University Print Center, University of Oslo II Summary The subject of this thesis is tradition and the current trend of tea culture in China. In order to answer the following three questions “ whether the current tea culture phenomena can be called “tradition” or not; what are the changes in tea cultural tradition and what are the new features of the current trend of tea culture; what are the endogenous and exogenous factors which influenced the change in the tea drinking tradition”, I did literature research from ancient tea classics and historical documents to summarize the development history of Chinese tea culture, and used two month to do fieldwork on teahouses in Xi’an so that I could have a clear understanding on the current trend of tea culture. It is found that the current tea culture is inherited from tradition and changed with social development. Tea drinking traditions have become more and more popular with diverse forms. -

The Tea Ceremony

The Tea Ceremony The Tea Ceremony by ReadWorks Most of Julie's friends' parents drank coffee. Some of them liked tea, too; but not like her parents did. Jill's family, Billy's family, and Tanya's family each had just two or three boxes of tea on a shelf, but Julie's had a whole cabinet dedicated to tea. No bags in boxes either; her parents drank loose-leaf tea only. "The real stuff," her dad called it. Packed tightly in rich red and gold tins, the Tang's collection included fragrant jasmine green tea; Longjing tea, a pan-fried green tea Julie preferred to call by its nickname, Dragon Well tea; roasted, curly-leaved oolong tea; lightly sweet white tea; and more. Every New Year-the Chinese New Year that is-her parents would have a traditional tea ceremony. That's the time when she would roll her eyes and slink out of the room. Her mom said it was an important cultural tradition, but Julie just thought it was B-O-R-I-N-G. (Or at least she assumed it would be if she ever stuck around for it.) However, now that she was 13 (an official teenager at last!), Julie felt different, more mature, and she was beginning to really enjoy history, thanks to her great social studies teacher. Julie decided it was time this New Year to take an interest in her own family and cultural history once she realized she actually knew very little. (She had only been to China once when she visited her grandparents as a five-year-old and her classes devoted equal time to studies of all the cultures of the world, not just that of the Chinese.) "Why do we have to do this tea ceremony every year?" Julie asked her mother, who was taking the clay teapots out of the cabinet reserved for special teapots and fancy dishes. -

Masterpiece Era Puerh GLOBAL EA HUT Contentsissue 83 / December 2018 Tea & Tao Magazine Blue藍印 Mark

GL BAL EA HUT Tea & Tao Magazine 國際茶亭 December 2018 紅 印 藍 印印 級 Masterpiece Era Puerh GLOBAL EA HUT ContentsIssue 83 / December 2018 Tea & Tao Magazine Blue藍印 Mark To conclude this amazing year, we will be explor- ing the Masterpiece Era of puerh tea, from 1949 to 1972. Like all history, understanding the eras Love is of puerh provides context for today’s puerh pro- duction. These are the cakes producers hope to changing the world create. And we are, in fact, going to drink a com- memorative cake as we learn! bowl by bowl Features特稿文章 37 A Brief History of Puerh Tea Yang Kai (楊凱) 03 43 Masterpiece Era: Red Mark Chen Zhitong (陳智同) 53 Masterpiece Era: Blue Mark Chen Zhitong (陳智同) 37 31 Traditions傳統文章 03 Tea of the Month “Blue Mark,” 2000 Sheng Puerh, Yunnan, China 31 Gongfu Teapot Getting Started in Gongfu Tea By Shen Su (聖素) 53 61 TeaWayfarer Gordon Arkenberg, USA © 2018 by Global Tea Hut 藍 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be re- produced, stored in a retrieval system 印 or transmitted in any form or by any means: electronic, mechanical, pho- tocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the copyright owner. n December,From the weather is much cooler in Taiwan.the We This is an excitingeditor issue for me. I have always wanted to are drinking Five Element blends, shou puerh and aged find a way to take us on a tour of the eras of puerh. Puerh sheng. Occasionally, we spice things up with an aged from before 1949 is known as the “Antique Era (號級茶時 oolong or a Cliff Tea. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 152 International Conference on Social science, Education and Humanities Research (ICSEHR 2017) Research on Chinese Tea Culture Teaching from the Perspective of International Education of Chinese Language Jie Bai Xi’an Peihua University, Humanities School Xi’an, China e-mail: [email protected] Abstract—This paper discusses the current situation of Chinese tea culture in teaching Chinese as a foreign language (TCFL) B. Chinese Tea Culture Teaching and points out that it is of great significance to introduce tea In May 2014, the Office of Chinese Language Council culture teaching under the background of global "Chinese International (Hanban) has promulgated the "International Popular", and finally puts forward some teaching strategies to Curriculum for Chinese Language Education (Revised bring inspiration for Chinese tea culture teaching. Edition)" (hereinafter referred to as the "Syllabus"), which refers to the "cultural awareness": "language has a rich Keywords-International Education of Chinese Language; cultural connotation. Teachers should gradually expand the Chinese Tea Culture;Teaching Strategies content and scope of culture and knowledge according to the students' age characteristics and cognitive ability, and help students to broaden their horizons so that learners can I. INTRODUCTION understand the status of Chinese culture in world With the rapid development of globalization, China's multiculturalism and its contribution to world culture. "[1] In language and culture has got more and more attention from addition, the "Syllabus" has also made a specific request on the world. More and more foreign students come to China to themes and tasks of cultural teaching, among which the learn Chinese and learn about Chinese culture and history, Chinese tea culture is one of the important themes.