'Does Anybody Here Want to Fight'… 'No, Not Really, but If You Care to Take a Swing at Me…' the Cultivation of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rvf 4 Sample Unit 9.Pdf

UNIT Culture and Identity NINE Mozambican woman with painted face 200 9781285173412_RVF4_Final_File.indd 200 1/16/14 1:07 PM FOCUS 1. What is a legend or story that you remember from your childhood? 2. What are some lessons that legends and ancient cultures try to teach us? Culture and Identity 201 9781285173412_RVF4_Final_File.indd 201 1/16/14 1:07 PM READING 1 Kung Fu Battles Academic Vocabulary to demonstrate to mature an opponent to found to modify proficient insufficient a myth Multiword Vocabulary to grit one’s teeth to look the part to hone a skill to make the case to keep up with to stretch the truth a leading role to talk one’s way into Reading Preview Preview. Look at the time line in Reading 1 on page 205. Then discuss the following questions with a partner or in a small group. 1. When was the Shaolin Temple founded? 2. What happened in 1928? Enter the modern world of 3. When did a lot of Americans learn about the Shaolin Kung Fu, an ancient Shaolin Temple? Why? form of defense. Follow the story of one Shaolin master, who must Topic vocabulary. The following words appear decide whether to star in a movie in Reading 1. Look at the words and answer the questions with a partner. or stick with tradition. brand monks cash registers robes disciples self-defense employees temple enlightenment training karate chop warfare 1. Which words are connected to fighting? 2. Which words are connected to business and money? 3. Which words suggest that the reading might be about religion and philosophy? Predict. -

I: Chinese Buddhism and Taoism

SPECIAL REPORT: The Battle for China’s Spirit I: Chinese Buddhism and Taoism Degree of Key findings persecution: 1 Revival: Chinese Buddhism and Taoism have revived Chinese significantly over the past 30 years from near extinction, Buddhism but their scale and influence pale in comparison to the LOW pre–Chinese Communist Party (CCP) era. With an Taoism estimated 185 to 250 million believers, Chinese VERY LOW Buddhism is the largest institutionalized religion in China. 2 Intrusive controls: A large body of regulations and Trajectory of bureaucratic controls ensure political compliance, but persecution: unfairly restrict religious practices that are routine in other countries. Unrealistic temple registration Chinese Buddhism requirements, infrequent ordination approvals, and official intervention in temple administration are among Consistent the controls that most seriously obstruct grassroots monastics and lay believers. Taoism Consistent 3 Under Xi Jinping: President Xi Jinping has essentially continued the policies of his predecessor, Hu Jintao, with some rhetorical adjustments. For CCP leaders, Chinese Buddhism and Taoism are seen as increasingly important channels for realizing the party’s political and economic goals at home and abroad. In a rare occurrence, a Chinese Buddhist monk was sentenced to prison in 2016 on politically motivated charges. 4 Commodification: Economic exploitation of temples for tourism purposes—a multibillion-dollar industry—has emerged as a key point of contention among the state, clergy, and lay believers. 5 Community response: Religious leaders and monks are becoming increasingly assertive in trying to negotiate free or relatively inexpensive access to temples, and are pushing back against commercial encroachment, often with success. 26 Freedom House Visitors walk past the statue of a bodhisat- tva in a scenic park in Zhejiang Province. -

Contesting the Commercialization and Sanctity of Religious Tourism In

Contesting the Commercialization and Sanctity of Religious Tourism in The Shaolin Monastery, China Abstract The Shaolin Monastery annually attracts millions of visitors from around the world. However, the overcommercialization of these sacred places may contradict the values and philosophies of Buddhism. This study aims to comprehensively understand the balance between commercialization and sanctity, engaging with 58 Chinese practitioners and educators in 7 focus groups. Participants articulated their expectation to avoid overcommercialization, and they discussed the conflicts between commercialization and sanctity to further explore on how to mitigate over commercialization. Based on the study findings, a balanced model of religious tourism development is proposed and specific recommendations are offered to sustainably manage religious sites. Keywords: Shaolin monastery, kung fu, culture, commercialization, sanctity, religion INTRODUCTION A popular Chinese saying states that “All martial arts under heaven arose out of the Shaolin Monastery.” The Shaolin Monastery is the birthplace of Dhyana (also known as Zen, a Buddhism philosophy that emphasizes internal meditation) and Shaolin kung fu, which evolved from Buddhism. This martial art tradition, which spanned for over 1,500 years, involves the Shaolin monks learning the Buddhism doctrines and practicing the Dhyana (Chan) philosophy in their martial arts. This practice has distinguished Shaolin kung fu from other types of Chinese kung fu (The Shaolin Monastery, 2010). The movie Shaolin Monastery released in 1982 established the global reputation of Chinese kung fu and the Shaolin Monastery. A number of movies are also made subsequently based on topics involving Chinese kung fu and the monastery. For example, the recent movie, The Grand Masters (2013), introduced kung fu worldwide as a fascinating element of the Chinese culture. -

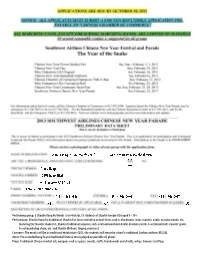

Performing Group: 8 Shaolin Kung Fu Monks 少林寺武僧, 37 Students of Shaolin Temple USA Aged 9 - 70+

Shaolin Temple USA 少林寺文化中心 Website: http://www.shaolinusa.us Diana Hong 5509 Geary Blvd. San Francisco, CA 94121 [email protected] 415 666-9966 415 666-9966 415 666-9977 45 N/A 50 Performing group: 8 Shaolin Kung Fu Monks 少林寺武僧, 37 students of Shaolin Temple USA aged 9 - 70+. Performance: Shaolin Kung Fu (traditional Shaolin Fist forms including animal forms such as the dragon, tiger, monkey, eagle, praying mantis, etc. featuring the Shaolin Snake Fist, Shaolin traditional weapons such as broadsword and shield, drunken sword, 3-sectioned staff , crescent spade, 9-sectioned whip chain, etc. and Shaolin Wellness Qigong exercises.) Costumes: The monks will be in traditional monk attire 僧服; the students will wear the school’s traditional Luohan uniform 罗汉服. Music: Pre-recorded kung fu and traditional Chinese music played on portable CD player. Props: Traditional Chinese martial arts weapons such as spears, swords, staff s, broadswords and shields, whips; banners and fl ags Southwest Airlines Chinese New Year Parade 2013 Application - Shaolin Temple USA (page 2) WHAT DO YOU PLAN TO DO IN THE 2013 CHINESE NEW YEAR PARADE? IF YOU ARE A MARCHING BAND, LIST THE MUSIC THAT YOU WILL PLAY. The procession will stop at designated intervals and perform spectacular Shaolin Kung Fu to pre-recorded music: • Shaolin Animal forms featuring the “Shaolin Snake Fist” 《少林蛇拳》 • Shaolin Wellness exercies 少林养生功 - from the 1,500-year old healing system for body and mind including the ancient Shaolin manuals Yijinjingjing (Change of Sinews 易筋经)and Xisuijingjing (Bone Marrow Cleansing 洗髓经). • The famous 18 traditional Shaolin weapons such as spears, swords, staff s, crescent spades, whips, hooks, dadao, etc. -

Tracking B Odhidharma

/.0. !.1.22 placing Zen Buddhism within the country’s political landscape, Ferguson presents the Praise for Zen’s Chinese Heritage religion as a counterpoint to other Buddhist sects, a catalyst for some of the most revolu- “ A monumental achievement. This will be central to the reference library B)"34"35%65 , known as the “First Ances- tionary moments in China’s history, and as of Zen students for our generation, and probably for some time after.” tor” of Zen (Chan) brought Zen Buddhism the ancient spiritual core of a country that is —R)9$%: A4:;$! Bodhidharma Tracking from South Asia to China around the year every day becoming more an emblem of the 722 CE, changing the country forever. His modern era. “An indispensable reference. Ferguson has given us an impeccable legendary life lies at the source of China and and very readable translation.”—J)3! D54") L))%4 East Asian’s cultural stream, underpinning the region’s history, legend, and folklore. “Clear and deep, Zen’s Chinese Heritage enriches our understanding Ferguson argues that Bodhidharma’s Zen of Buddhism and Zen.”—J)5! H5<4=5> was more than an important component of China’s cultural “essence,” and that his famous religious movement had immense Excerpt from political importance as well. In Tracking Tracking Bodhidharma Bodhidharma, the author uncovers Bodhi- t r a c k i n g dharma’s ancient trail, recreating it from The local Difang Zhi (historical physical and textual evidence. This nearly records) state that Bodhidharma forgotten path leads Ferguson through established True Victory Temple China’s ancient heart, exposing spiritual here in Tianchang. -

CHINA: the Economics of Religious Freedom

FORUM 18 NEWS SERVICE, Oslo, Norway http://www.forum18.org/ The right to believe, to worship and witness The right to change one's belief or religion The right to join together and express one's belief This article was published by F18News on: 16 August 2006 CHINA: The Economics of Religious Freedom By Magda Hornemann, Forum 18 News Service <http://www.forum18.org> Economics has a large effect on China's religious freedom, Forum 18 News Service notes. Factors such as the need of religious communities for non-state income, significant regional wealth disparities, conflicts over economic interests, and artificially-induced dependence on the state income all provide the state with alternative ways of exercising control over religious communities. Examples where economics has a noticeable effect on religious freedom include, to Forum 18's knowledge, the Buddhist Shaolin Temple's business enterprises, clashes between Buddhist temple personnel and the tourism industry, the demolition of a Protestant church in Zhejiang Province, the expropriation of Catholic properties in Xian and Tianjin for commercial development, the dependence of senior state-sanctioned religious leaders on the state for personal income, and competition between and amongst registered and unregistered religious groups. Perhaps the greatest beneficiary of economic clashes is the state, which can use both control of income and also favouritism in economic conflicts to restrict religious freedom. China's country-wide desire and need to make money has a large, if under-reported, effect on religious communities and the country's religious freedom. The need for non-state income, significant regional disparities in wealth, conflicts over economic interests, the need for good relations with the state to enable income generation, and artificially-induced dependence on the state for some income - particularly amongst some senior religious figures - all combine to provide the state with alternative ways of exercising control and blocking true religious freedom in China. -

“B O D H I D H a R M A”

PLENARY SESSION LECTURE “B O D H I D H A R M A” FROM MYTH TO REALITY by JOSEPH ARANHA Chairman Asian Arts and Cultural Council New York, U S A at the INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR on the CONTRIBUTIONS OF TAMILS TO THE COMPOSITE CULTURE OF ASIA in CHENNAI, INDIA. 16TH, 17TH AND 18TH JANUARY 2011 celebrating the “SILVER JUBILEE” of the “THE INSTITUTE OF ASIAN STUDIES” All material in this presentation has been copyrighted and any reproduction in any form is strictly prohibited. Permission for reproduction can be obtained by writing to [email protected] Chennai, India – It is my pleasure, after about thirty years of on-and-off research, to be able to throw light with conclusive evidence on the existence of Bodhidharma, the 28th Patriarch after the Buddha in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition. Though he is an icon in the Mahayana tradition, many so-called scholars and researchers still stubbornly continue to insist that he is a myth. Unfortunately their research, and thereby their conclusion, lacks substance. To give one example, a book, in fact two books, written by a Father Damoulin, a Jesuit priest in Japan tries its very best to prove Bodhidharma a myth because of wrong dates found in various records of the 5th, 6th and 7th centuries. But, one must remember that those books and records were written in the 5th and following centuries in various parts of China. Those were the days when there was no electricity, no computers, no phones and no peer review as we have it today and hence mistakes were bound to occur. -

No, Not Really, but If You Care to Take a Swing At

© Idōkan Poland Association “IDO MOVEMENT FOR CULTURE. Journal of Martial Arts Anthropology”, Vol. 19, no. 1S (2019), pp. 25–31 DOI: 10.14589/ido.19.1S.5 ANTHROPOLOGY Stefania Skowron-Markowska Institute of Classical, Mediterranean and Oriental Studies of the University of Wroclaw (Poland) e-mail: [email protected] Chinese guó shù (國術 “national art”) in Shaolin Temple Submission: 12.11.2018; acceptance: 12.01.2019 Key words: Shaolin temple, Chinese martial arts, kung fu, martial arts tourism, guo shu Abstract Background. The Shaolin monastery offers a meeting with Chinese culture by implementing a guo shu, program that the Chinese government supports and helps develop. Guo shu, implemented during the republican era in China supported the development of national arts, including Chinese martial arts. It was developed to rebuild a sense of patriotism and national pride in the Chinese nation after the Opium Wars and the Boxer Rebellion. Problem and Aim. The purpose of this paper is to present the new challenges that the Shaolin monastery has faced in modern times and how is it currently implemented based on the guo shu concept. Because the Shaolin monastery is also seen as a great emissary of the culture of the Middle Kingdom, students also have the opportunity to get acquainted with Chinese culture. Methods. The theoretical perspective is based on the sociology and anthropology of martial arts. For the theoretic background, an analysis of specialist text and documents was applied. The author also applied participant observation and interviews with foreign Shaolin kung fu students, visiting Shaolin temple in 2007, 2012. -

Reexamining the Categories and Canons of Chinese Buddhist Healing

Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies (2015, 28: 35–66) New Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies ᷕ厗ἃ⬠⬠⟙䫔Ḵ⋩ℓ㛇ġ 枩 35–66炷㮹⚳ᶨ䘦暞⚃⸜炸炻㕘⊿烉ᷕ厗ἃ⬠䞼䨞 ISSN: 2313-2000 e-ISSN: 2313-2019 Reexamining the Categories and Canons of Chinese Buddhist Healing C. Pierce Salguero Assistant Professor, Asian History & Religious Studies The Abington College of the Pennsylvania State University Abstract Texts related to healing are abundant in the Chinese Buddhist corpus, with hundreds of relevant treatises or chapters extant today from all periods of Chinese history. Generations of authors from the medieval period to the present day have ascribed a great degree of importance to codifying and anthologizing this particular area of Buddhist knowledge. This paper discusses the organizational categories and textual canons that have predominated in this exegetical tradition. I outline the emergence of the first syntheses in the medieval period, continuities in later authors’ treatment of the topic, and the modification of those approaches to fit with modern scientific medicine. I then critique the reinscription of these exegetical approaches in Western scholarship, and identify several ways to move beyond these traditional categories and canons in future research. Keywords: Buddhist medicine, Categories, Encyclopedias, Daoxuan, Paul Demiéville 36 Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies Volume 28 (2015) 慵㕘⮑夾ᷕ⚳ἃ㔁慓䗪䘬栆⇍冯㔯䌣 䙖䇦㕗炽岥䇦味伭 Ṇⶆ㬟⎚冯⬿㔁䞼䨞≑䎮㔁㌰ 伶⚳屻⢽㱽⯤Ṇⶆ䩳⣏⬠旧屻枻⬠昊 㐀天 ⛐ᷕ⚳ἃ㔁䘬㔯䌣ᷕ⏓㚱寸䘬慓䗪屯㕁炻⽆⎌军Ṳ㚱㔠ẍ䘦妰䘬 㔯䪈冯叿ἄˤ㚱㔠ẋἄ⭞⮯㬌䈡㬲柀➇䘬ἃ㔁䞍嬀䶐个ㆸ㚠冯怠䶐㔯普ˤ 㛔㔯㍊妶⛐㬌慳佑 ⁛䴙ᷕ㖑ㆸ✳䘬栆⇍冯㔯䌣ˤ椾⃰㍷徘⛐ᷕᶾ䲨㗪 㛇↢䎦䘬㚨⇅䲣䴙ˣ⼴ẋ㈧多䘬ね㱩冯䁢怑ㅱ䎦ẋ慓⬠ 䘬㓡忈ˤ㍍ 叿炻姽㜸䎦ẋ大㕡⬠侭⮵忁ṃ慳佑㕡⺷䘬慵徘炻᷎㊯↢⛐㛒Ἦ䘬䞼䨞ᷕ崭 崲忁ṃ⁛䴙栆⇍冯㔯䌣䘬ᶨṃ㕡㱽ˤ 斄挝娆烉 ἃ慓ˣἃ㔁慓⬠ˣ䕭劎ˣ岵䕭ˣ忻⭋ Reexamining the Categories and Canons of Chinese Buddhist Healing 37 Texts related to healing are abundant in the Chinese Buddhist corpus, with hundreds of relevant treatises or chapters extant today from all periods of Chinese history.1 This body of literature includes both texts translated from Indic languages (mainly dating from between the second and eleventh centuries), as well as those that were composed domestically in China. -

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui/Sadler's Wells London

Tuesday–Thursday, October 16–18, 2018 at 7:30 pm Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui/Sadler’s Wells London Sutra A Sadler’s Wells London Production, co-produced with Athens Festival, Grec Festival de Barcelona, Grand Théâtre de Luxembourg, La Monnaie Brussels, Festival d’Avignon, Fondazione Musica per Roma, and Shaolin Cultural Communications Company With the blessing of the Abbot of Song Shan Shaolin Temple Master Shi Yongxin This performance is approximately one hour long and will be performed without intermission. Sutra is made possible in part by The Joelson Foundation and The Harkness Foundation for Dance. Major endowment support for contemporary dance and theater is provided by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Endowment support for the White Light Festival presentation of Sutra is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Steinway Piano Please make certain all your electronic devices Rose Theater are switched off. Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall WhiteLightFestival.org The White Light Festival 2018 is made possible by UPCOMING WHITE LIGHT FESTIVAL EVENTS: The Shubert Foundation, The Katzenberger Foundation, Inc., Laura Pels International Friday–Saturday, October 19–20, at 7:30 pm in the Foundation for Theater, The Joelson Foundation, Gerald W. Lynch Theater, John Jay College The Harkness Foundation for Dance, Great Borderline (New York premiere) Performers Circle, Chairman’s Council, and Friends Company Wang Ramirez of Lincoln Center Honji Wang and Sébastien Ramirez , artistic direc - tion and choreography Public support is provided by New York State Louis Becker, Johanna Faye, Saïdo Lehlouh, Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Alister Mazzotti, Sébastien Ramirez, Honji Andrew M. -

ISBN: 9798661286116 Softcover Print First Edition July 2, 2020

© 2020 Ti: Rebuilding the North Shaolin Monastery Subtitle: 2010 to 2020 By: Gregory Brundage ISBN: 9798661286116 Softcover Print First Edition July 2, 2020 The Chinese characters at the beginning of chapters, along with Pinyin and English definitions came from: https://www.mdbg.net/chinese/dictionary which were very useful for translations, along with https://fanyi.baidu.com. The views and opinions expressed in this book are solely those of the author and do not represent those of the Shaolin Temple or other spiritual/religious organizations. i Dedication This book is dedicated to the spirits and memories of all those who have had the discipline and courage to fight for truth, justice and the greater good, as well as those who have toiled in the fields of inequity while living by and preserving the wisdom of those before us. This includes but is not limited to the good Shaolin monks, those of Wudangshan and millions of other people around the world – past and present. May their spirits be remembered in reverence and preserved as a light for humanity especially at times when all may seem lost. ii INTRODUCTION TO REBUILDING THE NORTH SHAOLIN MONASTERY ARTICLE SERIES ................................................................ IV PILGRIMAGE TO THE TRUE NORTH SHAOLIN TEMPLE PART I REBIRTH ............... 1 REBUILDING NORTH SHAOLIN TEMPLE PART II DISCOVERY...............................10 REBUILDING NORTH SHAOLIN TEMPLE PART III PROFESSOR GAO .....................28 REBUILDING NORTH SHAOLIN TEMPLE PART IV WATER DRAGON ....................38 REBUILDING NORTH SHAOLIN TEMPLE PART V GRANDMOTHER WANG AND THE BUDDHA ...........................................................................................................46 REBUILDING NORTH SHAOLIN TEMPLE PART VI INSIDE .....................................59 REBUILDING NORTH SHAOLIN TEMPLE PART VII RELEASE .................................87 REBUILDING NORTH SHAOLIN TEMPLE PART VIII SPIRIT OF THE MASTERS .... -

Nicola Schneider Une Journée

© Humensis Sous la direction de Adeline Herrou Une journée dans une vie, une vie dans une journée Des ascètes et des moines aujourd’hui 299437EWZ_HERROU_cs6_pc.indd 5 20/07/2018 11:24:12 © Humensis Publié avec le concours de l’université Paris Nanterre et du Laboratoire d’ethnologie et de sociologie comparative Illustrations de couverture (de gauche à droite en haut puis en bas) : un yogi hindou, un moine orthodoxe, une nonne copte et une ḍākinī tibétaine. © Illustrations de Frédéric Desportes à partir de photographies des auteurs. ISBN 978‑2‑13‑073325‑6 Dépôt légal – 1re édition : 2018, août © Presses Universitaires de France / Humensis 170 bis, boulevard du Montparnasse, 75014 Paris 299437EWZ_HERROU_cs6_pc.indd 4 20/07/2018 11:24:12 © Humensis 299437EWZ_HERROU_cs6_pc.indd 318 20/07/2018 11:24:23 © Humensis 13 Khandro Chöchen, une ḍākinī tibétaine en chair et en os Nicola Schneider Il est 9 heures du matin et je suis sur le point d’arriver au nou‑ veau domicile de Khandro Chöchen à McLeod Ganj, près de Dha‑ ramsala en Inde, où elle s’est réfugiée depuis 20041. Il s’agit de deux petites pièces qui sont louées pour elle et ses assistants par le bureau privé du quatorzième Dalaï‑lama. Le rendez‑vous a été pris la veille auprès de Norbu, un moine dévoué qui l’assiste dans ses fonctions religieuses mais aussi, plus généralement, dans sa vie quotidienne. Je frappe d’abord à la porte de la cuisine où dorment aussi ses deux autres assistants, Tenzin Özer, son fils adoptif, et Jamyang, le fils de la meilleure amie de Khandro Chöchen.