Contesting the Commercialization and Sanctity of Religious Tourism In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rvf 4 Sample Unit 9.Pdf

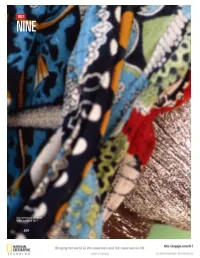

UNIT Culture and Identity NINE Mozambican woman with painted face 200 9781285173412_RVF4_Final_File.indd 200 1/16/14 1:07 PM FOCUS 1. What is a legend or story that you remember from your childhood? 2. What are some lessons that legends and ancient cultures try to teach us? Culture and Identity 201 9781285173412_RVF4_Final_File.indd 201 1/16/14 1:07 PM READING 1 Kung Fu Battles Academic Vocabulary to demonstrate to mature an opponent to found to modify proficient insufficient a myth Multiword Vocabulary to grit one’s teeth to look the part to hone a skill to make the case to keep up with to stretch the truth a leading role to talk one’s way into Reading Preview Preview. Look at the time line in Reading 1 on page 205. Then discuss the following questions with a partner or in a small group. 1. When was the Shaolin Temple founded? 2. What happened in 1928? Enter the modern world of 3. When did a lot of Americans learn about the Shaolin Kung Fu, an ancient Shaolin Temple? Why? form of defense. Follow the story of one Shaolin master, who must Topic vocabulary. The following words appear decide whether to star in a movie in Reading 1. Look at the words and answer the questions with a partner. or stick with tradition. brand monks cash registers robes disciples self-defense employees temple enlightenment training karate chop warfare 1. Which words are connected to fighting? 2. Which words are connected to business and money? 3. Which words suggest that the reading might be about religion and philosophy? Predict. -

Download Article

6th International Conference on Social Network, Communication and Education (SNCE 2016) The Development and Reflection on the Traditional Martial Arts Culture Zhenghong Li1, a and Zhenhua Guo1, b 1College of Sports Science, Jishou University Renmin South Road 120, Jishou City Hunan Province, China [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: Martial arts; Martial arts culture; Development; Reflection Abstract. Martial arts is an outstanding spiritual creation through the historical choice. As a kind of cultural form, it cnnotations. In this paper, using the research methods of literature, logic reasoning and so on, the interontains the rich cultural copretation of the traditional martial arts culture has been researched. The results show that The Chinese classical philosophy is the thought origin of the martial arts culture. Worshiping martial arts and advocating moral character are the important connotation of Chinese wushu culture. On the pre - qin period, contention of a hundred schools of thought in the field of ideology and culture make martial arts begin showing the cultural characteristics. The secularization of Song-Ming Neo-Confucianism makes martial arts gradually develop into a mature culture carrier. At the same time, this paper also analyzes the external martial arts’ impact on Chinese wushu; Western physical education’ misreading on Chinese wushu culture; The helpless of Chinese Wushu in In an age of extravagance and waste; The "disenchantment" of Chinese wushu culture in modern society; the condition and hope of Chinese martial arts culture. In view of this, this article calls for China should take great effort to study martial arts, refine, package and promote Chinese Wushu. -

Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China Democratic Revolution in China, Was Launched There

Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy The Great Wall of China In c. 220 BC, under Qin Shihuangdi (first emperor of the Qin dynasty), sections of earlier fortifications were joined together to form a united system to repel invasions from the north. Construction of the Great Wall continued for more than 16 centuries, up to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), National Emblem of China creating the world's largest defense structure. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. The design of the national emblem of the People's Republic of China shows Tiananmen under the light of five stars, and is framed with ears of grain and a cogwheel. Tiananmen is the symbol of modern China because the May 4th Movement of 1919, which marked the beginning of the new- Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China democratic revolution in China, was launched there. The meaning of the word David M. Darst, CFA Tiananmen is “Gate of Heavenly Succession.” On the emblem, the cogwheel and the ears of grain represent the working June 2011 class and the peasantry, respectively, and the five stars symbolize the solidarity of the various nationalities of China. The Han nationality makes up 92 percent of China’s total population, while the remaining eight percent are represented by over 50 nationalities, including: Mongol, Hui, Tibetan, Uygur, Miao, Yi, Zhuang, Bouyei, Korean, Manchu, Kazak, and Dai. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. Please refer to important information, disclosures, and qualifications at the end of this material. Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy Table of Contents The Chinese Dynasties Section 1 Background Page 3 Length of Period Dynasty (or period) Extent of Period (Years) Section 2 Issues for Consideration Page 65 Xia c. -

Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies

NEWSLETTER | The American Philosophical Association Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies SPRING 2018 VOLUME 17 | NUMBER 2 FROM THE GUEST EDITOR Manyul Im Ways of Philosophy, Ways of Practice SUBMISSION GUIDELINES AND INFORMATION ARTICLES Bin Song “Three Sacrificial Rituals” (sanji) and the Practicability of Ruist (Confucian) Philosophy Steven Geisz Traditional Chinese Body Practice and Philosophical Activity Alexus McLeod East Asian Martial Arts as Philosophical Practice VOLUME 17 | NUMBER 2 SPRING 2018 © 2018 BY THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL ASSOCIATION ISSN 2155-9708 APA NEWSLETTER ON Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies PRASANTA BANDYOPADHYAY AND JEELOO LIU, CO-EDITORS VOLUME 17 | NUMBER 2 | SPRING 2018 FROM THE GUEST EDITOR SUBMISSION GUIDELINES AND Ways of Philosophy, Ways of Practice INFORMATION Manyul Im GOAL OF THE NEWSLETTER ON ASIAN AND UNIVERSITY OF BRIDGEPORT ASIAN-AMERICAN PHILOSOPHERS For this issue of the newsletter, my goal was to enable The APA Newsletter on Asian and Asian-American wanderings in some lightly beaten paths of philosophical Philosophers and Philosophies is sponsored by the APA exploration, leading the reader through some unusual Committee on Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and foliage. The authors here were invited to submit pieces Philosophies to report on the philosophical work of Asian about “practices” of Asian philosophy and encouraged to and Asian-American philosophy, to report on new work in discuss social and physical activities that bear relevance to Asian philosophy, and to provide a forum for the discussion particular traditions of inquiry and that potentially provide of topics of importance to Asian and Asian-American ways of “thinking”—in a broad sense—that are disruptive philosophers and those engaged with Asian and Asian- of the usual ways of imagining philosophy. -

Claiming Martial Arts in the Qing Period

Internal Cultivation or External Strength?: Claiming Martial Arts in the Qing Period Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ian McNally, B.A. Graduate Program in East Asian Studies The Ohio State University 2019 Thesis Committee: Ying Zhang, Adviser Morgan Liu Patricia Sieber i Copyright by Ian McNally 2019 ii Abstract Martial arts in China has always had multiple meanings, depending on the context in which it was understood. This project seeks to evaluate what the different meanings of martial arts changed over the Qing period and how different people employed these understandings at different times and in different circumstances. By placing martial arts as the focal point of analysis, something rarely seen in academic scholarship, this project highlights how there the definition of martial arts has always been in flux and it is precisely that lack of definition that has made it useful. This project begins by focusing on establishing a historical overview of the circumstances during the Qing period within which martial arts developed. It also analyzes and defines both the important analytical and local terminology used in relation to discourse surrounding the martial arts. Chapter 1 looks at official documents and analyzes how the Qing court understood martial arts as a means of creating a political narrative and how the form of that narrative changed during the Qing, depending on the situations that required court intervention. Chapter 2 will analyze how Han martial artists employed their martial arts as a means of developing or preserving a sense of ethnic strength. -

The World Through His Lens, Steve Mccurry Photographs

The World through His Lens, Steve McCurry Photographs Glossary Activist - An activist is a person who campaigns for some kind of social change. When you participate in a march protesting the closing of a neighborhood library, you're an activist. Someone who's actively involved in a protest or a political or social cause can be called an activist. Alms - Money or food given to poor people. Synonyms: gifts, donations, offerings, charity. Ashram (in South Asia) - A place of religious retreat: a house, apartment or community, for Hindus. Bindi - Bindi is a bright dot of red color applied in the center of the forehead close to the eyebrow worn by Hindu or Jain women. Bodhi Tree - The Bodhi Tree, also known as Bo and "peepal tree" in Nepal and Bhutan, was a large and very old sacred fig tree located in Bodh Gaya, India, under which Siddhartha Gautama, the spiritual teacher later known as Gautama Buddha, is said to have attained enlightenment, or Bodhi. The term "Bodhi Tree" is also widely applied to currently existing trees, particularly the Sacred Fig growing at the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, which is a direct descendant planted in 288 BC from the original specimen. Buddha - 566?–c480 b.c., Indian religious leader: founder of Buddhism. Buddhism - A religion, originated in India by Buddha and later spreading to China, Burma, Japan, Tibet, and parts of southeast Asia. Buddhists believe that life is full of suffering, which is caused by desire. To stop desiring things is to stop the suffering. If a Buddhists accomplishes this, he or she is said to have obtained Enlightenment, like The Buddha. -

Kung-Fu – Musings on the Philosophical Background of Chinese Martial Arts

Kung-fu – Musings on the philosophical background of Chinese Martial Arts Karl-Heinz Pohl (Trier) Until the era of Mao Zedong, China had the reputation of a pacifist country. This image derives not only from the classical scriptures – Confucians have held a deep disregard for fighting and war, upholding instead harmonic relationships between people and nations. Daoists likewise despised aggression. But also early Western observers of China, such as the Jesuit missionaries in the 17th century, confirmed these impressions: They noticed that the Chinese, in their pacifistic attitude and disregard for military matters, lived up to the "higher teachings of Christ". But as Louis Daniel LeComte, a French Jesuit, remarked warningly in 1696: "By these restraints, Chinese politics may prevent uproar in the interior, but it risks for its people being involved in wars with foreign powers which might be even more dangerous." Only two hundred years later, LeComte's prognostic warnings turned into reality during the Opium wars with the European powers.1 And yet, throughout Chinese history, there had been continuous struggles and wars just like everywhere else. This contradiction between apparent pacifism and warlike reality might be explained by the familiar contradiction between ideal and reality. To maintain certain ideals in a society does not necessarily mean that these ideals will be put into practice. Considering two thousand years of Christian history in Europe, one could dismiss the Christian ideals of peace and charity as rather unrealistic. At the same time, these very ideals are, in a secular manner, still the guidelines of Western and even the United Nations' policy making, although they are still constantly being offended. -

'Does Anybody Here Want to Fight'… 'No, Not Really, but If You Care to Take a Swing at Me…' the Cultivation of A

© Idōkan Poland Association “IDO MOVEMENT FOR CULTURE. Journal of Martial Arts Anthropology”, Vol. 17, no. 2 (2017), pp. 24–33 DOI: 10.14589/ido.17.2.3 TOURISM OF MARTIAL ARTS. SOCIOLOGY & ANTHROPOLOGY OF TOURISM Wojciech J. Cynarski1(ABDEFG), Pawel Swider1(BDE) 1 University of Rzeszow, Rzeszow (Poland) e-mail: [email protected] The journey to the cradle of martial arts: a case study of martial arts’ tourism Submission: 14.09.2016; acceptance: 27.12.2016 Key words: wushu, Shaolin, cultural tourism, anthropology of martial arts Abstract Background. The study presents the account of a trip to the Shaolin monastery within the anthropological framework of martial arts and concept of martial arts tourism. Problem. The aim of the paper is to show the uniqueness of the place of destination of many tourists including the authors. The study is meant as a contribution to the further study on the tourism of martial arts. Method. The main method used here is participant observation, and additionally, an analysis of the subject literature. This is par- tially a case study, and an analysis of facts, literature and symbolism. The method of visual sociology was also used (the main material are photos taken during the trip). Results. The authors conducted field research in the area ofDengfeng: Shaolin and Fawang temples cultivating kung-fu. The descrip- tion is illustrated with photographs (factual material) and analysis of facts. It was found that in the case of the Shaolin centre both commercialisation of martial arts and tourism occurred. However, as wushu schools around the historic monastery are function- ing, this is still an important place for martial arts, especially related to the Chinese tradition. -

I: Chinese Buddhism and Taoism

SPECIAL REPORT: The Battle for China’s Spirit I: Chinese Buddhism and Taoism Degree of Key findings persecution: 1 Revival: Chinese Buddhism and Taoism have revived Chinese significantly over the past 30 years from near extinction, Buddhism but their scale and influence pale in comparison to the LOW pre–Chinese Communist Party (CCP) era. With an Taoism estimated 185 to 250 million believers, Chinese VERY LOW Buddhism is the largest institutionalized religion in China. 2 Intrusive controls: A large body of regulations and Trajectory of bureaucratic controls ensure political compliance, but persecution: unfairly restrict religious practices that are routine in other countries. Unrealistic temple registration Chinese Buddhism requirements, infrequent ordination approvals, and official intervention in temple administration are among Consistent the controls that most seriously obstruct grassroots monastics and lay believers. Taoism Consistent 3 Under Xi Jinping: President Xi Jinping has essentially continued the policies of his predecessor, Hu Jintao, with some rhetorical adjustments. For CCP leaders, Chinese Buddhism and Taoism are seen as increasingly important channels for realizing the party’s political and economic goals at home and abroad. In a rare occurrence, a Chinese Buddhist monk was sentenced to prison in 2016 on politically motivated charges. 4 Commodification: Economic exploitation of temples for tourism purposes—a multibillion-dollar industry—has emerged as a key point of contention among the state, clergy, and lay believers. 5 Community response: Religious leaders and monks are becoming increasingly assertive in trying to negotiate free or relatively inexpensive access to temples, and are pushing back against commercial encroachment, often with success. 26 Freedom House Visitors walk past the statue of a bodhisat- tva in a scenic park in Zhejiang Province. -

A Philosophical Look at the Asian Martial Arts by Barry Allen Michael Wert Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History, Department of 6-1-2016 Review of Striking Beauty: A Philosophical Look at the Asian Martial Arts by Barry Allen Michael Wert Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Philosophy in Review, Vol. 36, No. 3 (June 2016): 91-93. Permalink. © 2016 University of Victoria. Used with permission. Philosophy in Review XXXVI (June 2016), no. 3 Barry Allen. Striking Beauty: A Philosophical Look at the Asian Martial Arts. Columbia University Press 2015. 272 pp. $30.00 USD (Hardcover ISBN 9780231172721). Recently, the martial arts have received greater attention from English speaking scholars, mostly in the humanities and some social sciences (Japanese and Chinese language scholarship, absent in this volume, have been around much longer.) There are sociological and anthropological studies of martial arts practice and practitioners, works that analyze martial arts in various media with martial arts literature, theater, and film studies leading this field, and the occasional historical monograph. There is even a newly established journal, Martial Arts Studies, with an affiliated annual conference. Like other academic martial arts monographs, Allen brings his academic expertise, in this case philosophy, into conversation with his hobby. He uses his knowledge of philosophy to ask whether there can be beauty in an activity that, he argues, was originally intended to train people for violence. He wrestles with the aesthetic qualities of martial arts on the one hand and, on the other, the ethical problem posed by participating in what seems to be an art created for violence. Along the way he uses martial arts as a lens for describing Chinese philosophy because all martial arts in East Asia were influenced by the philosophical and religious traditions that originated or changed in China. -

Gushan: the Formation of a Chan Lineage During the Seventeenth Century and Its Spread to Taiwan

Gushan: the Formation of a Chan Lineage During the Seventeenth Century and Its Spread to Taiwan Hsuan-Li Wang Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Hsuan-Li Wang All rights reserved ABSTRACT Gushan: the Formation of a Chan Lineage During the Seventeenth Century and Its Spread to Taiwan Hsuan-Li Wang Taking Gushan 鼓山 Monastery in Fujian Province as a reference point, this dissertation investigates the formation of the Gushan Chan lineage in Fujian area and its later diffusion process to Taiwan. From the perspective of religion diffusion studies, this dissertation investigates the three stages of this process: 1. the displacement of Caodong 曹洞 Chan center to Fujian in the seventeenth century; 2. Chinese migration bringing Buddhism to Taiwan in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) and 3. the expansion diffusion activities of the institutions and masters affiliated with this lineage in Taiwan during the Japanese rule (1895-1945), and the new developments of humanistic Buddhism (renjian fojiao 人間佛教) after 1949. In this spreading process of the Gushan Chan lineage, Taiwanese Buddhism has emerged as the bridge between Chinese and Japanese Buddhism because of its unique historical experiences. It is in the expansion diffusion activities of the Gushan Chan lineage in Taiwan that Taiwanese Buddhism has gradually attained autonomy during the Japanese rule, leading to post-war new developments in contemporary humanistic Buddhism. Table of Contents List of Chart, Maps and Tables iii Acknowledgements iv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1. Research Motives and Goals 2 2. -

Conference Brochure

The 9th International Symposium on Diagnosis of Environmental Health by Remote Sensing (DEHRS) and The Workshop of DEHRS on The Belt & Road (WDEHRS on B&R) The 9th International Symposium on Diagnosis of Environmental Health by Remote Sensing (DEHRS) and The Workshop of DEHRS on The Belt & Road (WDEHRS on B&R) Conference Brochure ZHENGZHOU·CHINA | AUGUST 10-12 The 9th International Symposium on Diagnosis of Environmental Health by Remote Sensing (DEHRS) and The Workshop of DEHRS on The Belt & Road (WDEHRS on B&R) Contents Notes To Participants .................................................................................. 1 Conference Organizations ........................................................................... 5 Conference Arrangements & Agenda ....................................................... 10 Introductions Of The Host & Organizer Units…………………….……20 Tips About Weather & Staff Contact...……………………………….....23 Appendix: Intro of Experts and Report Abstracts ...………………...….24 The 9th International Symposium on Diagnosis of Environmental Health by Remote Sensing (DEHRS) and The Workshop of DEHRS on The Belt & Road (WDEHRS on B&R) Notes to Participants Dear Delegates, Welcome to the beautiful Zhengzhou City (Capital of Henan Province) to attend the 9th International Symposium on Diagnosis of Environmental Health by Remote Sensing (DEHRS) and the Workshop of DEHRS on The Belt & Road (WDEHRS on B&R). First of all, let’s give you a brief introduction about Zhengzhou and Henan Province. Henan Province has a long history and culture. It is the root of Chinese ancestors and the source of Chinese history and civilization. With splendid culture, outstanding people and celebrities, it is an important birthplace of Chinese surnames. Rich in resources, it is the main agricultural production areas and important mineral resources province. With a large population, it is a province with a large population, abundant labor resources and huge consumption market.