Parsi Theatrical Networks in Southeast Asia: the Contrary Case of Burma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Mentions

SPECIAL MENTIONS The following matters of Public Importance were laid on the Table with the permission of the Chair during the Session: — Sl.No. Date Name of the Member Subject Time taken Hrs.Mts. *1. 21-08- Shri Lalit Kishore Need to release funds for 2007 Chaturvedi renovation of National Highways in Rajasthan. 2. -do- Shri Motilal Vora Concern over the shortage of seeds with Chhattisgarh Seed Development Corporation. 3. -do- Shrimati Brinda Concern over import of wheat at a Karat high price. 4. -do- Shri Abu Asim Azmi Concern over delay in Liberhan 0-01 Commission Report. 5. -do- Shri Santosh Demand to ban toxic toys. Bagrodia 6. -do- Shrimati N.P. Durga Need to appoint at least two teachers in every school in the Sl.No. Date Name of the Member Subject Time taken Hrs.Mts. country. 7. -do- Shri Dharam Pal Demand to make strict laws to curb Sabharwal smear campaign by Media. 8. 21-08- Shri Thennala G. Demand to take measures to check 2007 Balakrishna Pillai outbreak of Chikunguniya and Dengue fever in Kerala. 9. -do- Shri Pyarelal Concern over unprecedented Khandelwal increase in the prices of medicines. 10. -do- Shri Jai Parkash Need to take advance measures to Aggarwal protect telecom and other services from probable dangers of strong solar rays. 11. -do- Shri Saman Pathak Demand to improve the condition of National Highways in the North- Eastern region. 12. -do- Shri Moinul Hassan Demand to re-constitute Jute 0-01 Advisory Board and Jute Development Council. Sl.No. Date Name of the Member Subject Time taken Hrs.Mts. -

Manipuri, Odia, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu)

Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) UNIVERSITY OF DELHI DEPARTMENT OF MODERN INDIAN LANGUAGES AND LITERARY STUDIES (Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Manipuri, Odia, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu) UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAMME (Courses effective from Academic Year 2015-16) SYLLABUS OF COURSES TO BE OFFERED Core Courses, Elective Courses & Ability Enhancement Courses Disclaimer: The CBCS syllabus is uploaded as given by the Faculty concerned to the Academic Council. The same has been approved as it is by the Academic Council on 13.7.2015 and Executive Council on 14.7.2015. Any query may kindly be addressed to the concerned Faculty. Undergraduate Programme Secretariat Preamble The University Grants Commission (UGC) has initiated several measures to bring equity, efficiency and excellence in the Higher Education System of country. The important measures taken to enhance academic standards and quality in higher education include innovation and improvements in curriculum, teaching-learning process, examination and evaluation systems, besides governance and other matters. The UGC has formulated various regulations and guidelines from time to time to improve the higher education system and maintain minimum standards and quality across the Higher Educational Institutions (HEIs) in India. The academic reforms recommended by the UGC in the recent past have led to overall improvement in the higher education system. However, due to lot of diversity in the system of higher education, there are multiple approaches followed by universities towards examination, evaluation and grading system. While the HEIs must have the flexibility and freedom in designing the examination and evaluation methods that best fits the curriculum, syllabi and teaching–learning methods, there is a need to devise a sensible system for awarding the grades based on the performance of students. -

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc Vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P. Bharucha, B.N. Kirpal PETITIONER: BOBBY ART INTERNATIONAL, ETC. Vs. RESPONDENT: OM PAL SINGH HOON & ORS. DATE OF JUDGMENT: 01/05/1996 BENCH: CJI, S.P. BHARUCHA , B.N. KIRPAL ACT: HEADNOTE: JUDGMENT: WITH CIVIL APPEAL NOS. 7523, 7525-27 AND 7524 (Arising out of SLP(Civil) No. 8211/96, SLP(Civil) No. 10519-21/96 (CC No. 1828-1830/96 & SLP(C) No. 9363/96) J U D G M E N T BHARUCHA, J. Special leave granted. These appeals impugn the judgment and order of a Division Bench of the High Court of Delhi in Letters Patent appeals. The Letters Patent appeals challenged the judgment and order of a learned single judge allowing a writ petition. The Letters Patent appeals were dismissed, subject to a direction to the Union of India (the second respondent). The writ petition was filed by the first respondent to quash the certificate of exhibition awarded to the film "Bandit Queen" and to restrain its exhibition in India. The film deals with the life of Phoolan Devi. It is based upon a true story. Still a child, Phoolan Devi was married off to a man old enough to be her father. She was beaten and raped by him. She was tormented by the boys of the village; and beaten by them when she foiled the advances of one of them. A village panchayat called after the incident blamed Phoolan Devi for attempting to entice the boy, who belonged to a higher caste. -

Research Paper Impact Factor

Research Paper IJBARR Impact Factor: 3.072 E- ISSN -2347-856X Peer Reviewed, Listed & Indexed ISSN -2348-0653 HISTORY OF INDIAN CINEMA Dr. B.P.Mahesh Chandra Guru * Dr.M.S.Sapna** M.Prabhudev*** Mr.M.Dileep Kumar**** * Professor, Dept. of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Karnataka, India. **Assistant Professor, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Karnataka, India. ***Research Scholar, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Karnataka, India. ***RGNF Research Scholar, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangothri, Mysore-570006, Karnataka, India. Abstract The Lumiere brothers came over to India in 1896 and exhibited some films for the benefit of publics. D.G.Phalke is known as the founding father of Indian film industry. The first Indian talkie film Alam Ara was produced in 1931 by Ardeshir Irani. In the age of mooki films, about 1000 films were made in India. A new age of talkie films began in India in 1929. The decade of 1940s witnessed remarkable growth of Indian film industry. The Indian films grew well statistically and qualitatively in the post-independence period. In the decade of 1960s, Bollywood and regional films grew very well in the country because of the technological advancements and creative ventures. In the decade of 1970s, new experiments were conducted by the progressive film makers in India. In the decade of 1980s, the commercial films were produced in large number in order to entertain the masses and generate income. Television also gave a tough challenge to the film industry in the decade of 1990s. -

Indian Theatre Autobiographies Kindle

STAGES OF LIFE : INDIAN THEATRE AUTOBIOGRAPHIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kathryn Hansen | 392 pages | 01 Dec 2013 | Anthem Press | 9781783080687 | English | London, United Kingdom Stages of Life : Indian Theatre Autobiographies PDF Book All you need to know about India's 2 Covid vaccines. Celebratory firing: yr-old killed at Lohri event in Talwandi Sabo village. Khemta dances may be performed on any occasion, and, at one time, were popular at weddings and pujas. For a full translation via Bengali see The Wonders of Vilayet , tr. First, he used Grose's phrases for descriptions of topics which Dean Mahomet did not know, most notably the cities of Surat and Bombay, and also classical quotations from Seneca and Martial. He never explained the reasons for this next immigration and, indeed, later omitted his years in Ireland from his autobiographical writings altogether. London: Anthem Press. Samples of 3 dead birds found negative in Ludhiana 9 hours ago. Other Formats Available: Hardback. India's artistic identity is deeply routed within its social, economical, cultural, and religious views. For privacy concerns, please view our Privacy Policy. The above passage can be taken as example of the Vaishnav value system within which Girish Ghosh would always configure the identity and work of an actor. Main article: Sanskrit drama. This imagination serves as a source of creative inspiration in later life for artists, writers, scientists, and anyone else who finds their days and nights enriched for having nurtured a deep inner life. CBSE schools begin offline classes 9 hours ago. In Baumer and Brandon , xvii—xx. Thousands of tractors to leave for Delhi on Jan 20 9 hours ago. -

EXIGENCY of INDIAN CINEMA in NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA

Annals of the Academy of Romanian Scientists Series on Philosophy, Psychology, Theology and Journalism 80 Volume 9, Number 1–2/2017 ISSN 2067 – 113x A LOVE STORY OF FANTASY AND FASCINATION: EXIGENCY OF INDIAN CINEMA IN NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA Abstract. The prevalence of Indian cinema in Nigeria has been very interesting since early 1950s. The first Indian movie introduced in Nigeria was “Mother India”, which was a blockbuster across Asia, Africa, central Asia and India. It became one of the most popular films among the Nigerians. Majority of the people were able to relate this movie along story line. It was largely appreciated and well received across all age groups. There has been a lot of similarity of attitudes within Indian and Nigerian who were enjoying freedom after the oppression and struggle against colonialism. During 1970’s Indian cinema brought in a new genre portraying joy and happiness. This genre of movies appeared with vibrant and bold colors, singing, dancing sharing family bond was a big hit in Nigeria. This paper examines the journey of Indian Cinema in Nigeria instituting love and fantasy. It also traces the success of cultural bonding between two countries disseminating strong cultural exchanges thereof. Keywords: Indian cinema, Bollywood, Nigeria. Introduction: Backdrop of Indian Cinema Indian Cinema (Bollywood) is one of the most vibrant and entertaining industries on earth. In 1896 the Lumière brothers, introduced the art of cinema in India by setting up the industry with the screening of few short films for limited audience in Bombay (present Mumbai). The turning point for Indian Cinema came into being in 1913 when Dada Saheb Phalke considered as the father of Indian Cinema. -

Dr Rajendra Mehta.Pdf

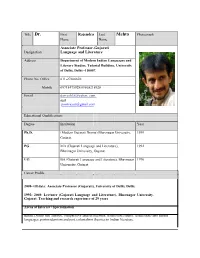

Title Dr. First Rajendra Last Mehta Photograph Name Name Associate Professor-Gujarati Designation Language and Literature Address Department of Modern Indian Languages and Literary Studies, Tutorial Building, University of Delhi, Delhi -110007. Phone No Office 011-27666626 Mobile 09718475928/09868218928 Email darvesh18@yahoo. com and [email protected] Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. (Modern Gujarati Drama) Bhavnagar University, 1999 Gujarat. PG MA (Gujarati Language and Literature), 1992 Bhavnagar University, Gujarat. UG BA (Gujarati Language and Literature), Bhavnagar 1990 University, Gujarat. Career Profile 2008- till date: Associate Professor (Gujarati), University of Delhi, Delhi. 1992- 2008: Lecturer (Gujarati Language and Literature), Bhavnagar University, Gujarat. Teaching and research experience of 29 years Areas of Interest / Specialization Indian Drama and Theatre, comparative Indian literature, translation studies, translations into Indian languages, postmodernism and post colonialism theories in Indian literature. Subjects Taught 1- Gujarati language courses (certificate, diploma, advanced diploma) 2-M.A (Comparative Indian Literature) Theory of literary influence, Tragedy in Indian literature, Ascetics and poetics 3-M.Phil (Comparative Indian Literature): Gandhi in Indian literature. Introduction to an Indian language- Gujarati Research Guidance M.Phil. student -12 Ph.D. student - 05 Details of the Training Programmes attended: Name of the Programme From Date To Date Duration Organizing Institution -

Death-Penalty-Pakistan

Report Mission of Investigation Slow march to the gallows Death penalty in Pakistan Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 Introduction and Background . 16 I. The legal framework . 21 II. A deeply flawed and discriminatory process, from arrest to trial to execution. 44 Conclusion and recommendations . 60 Annex: List of persons met by the delegation . 62 n° 464/2 - January 2007 Slow march to the gallows. Death penalty in Pakistan Table of contents Executive Summary. 5 Foreword: Why mobilise against the death penalty . 8 1. The absence of deterrence . 8 2. Arguments founded on human dignity and liberty. 8 3. Arguments from international human rights law . 10 Introduction and Background . 16 1. Introduction . 16 2. Overview of death penalty in Pakistan: expanding its scope, reducing the safeguards. 16 3. A widespread public support of death penalty . 19 I. The legal framework . 21 1. The international legal framework. 21 2. Crimes carrying the death penalty in Pakistan . 21 3. Facts and figures on death penalty in Pakistan. 26 3.1. Figures on executions . 26 3.2. Figures on condemned prisoners . 27 3.2.1. Punjab . 27 3.2.2. NWFP. 27 3.2.3. Balochistan . 28 3.2.4. Sindh . 29 4. The Pakistani legal system and procedure. 30 4.1. The intermingling of common law and Islamic Law . 30 4.2. A defendant's itinerary through the courts . 31 4.2.1. The trial . 31 4.2.2. Appeals . 31 4.2.3. Mercy petition . 31 4.2.4. Stays of execution . 33 4.3. The case law: gradually expanding the scope of death penalty . -

Crimeindelhi.Pdf

CRIME IN DELHI 2018 as against 2,23,077 in 2017. The yardstick of crime per lakh of population is generally used worldwide to compare The social churning is quite evident in the crime scene of the crime rate. Total IPC crime per lakh of population was 1289 capital. The Delhi Police has been closely monitoring the ever- crimes during the year 2018, in comparison to 1244 such changing modus operandi being adopted by criminals and crimes during last year. adapting itself to meet these new challenges head-on. The year 2018 saw a heavy thrust on modernization coupled with unrelenting efforts to curb crime. Here too, there was a heavy TOTAL IPC CRIME mix of the state-of-the-art technology with basic policing. The (per lakh of population) police maintained a delicate balance between the two and this 1500 was evident in the major heinous cases worked out this year. 1243.90 1289.36 Along with modern investigative techniques, traditional beat- 1200 1137.21 level inputs played a major role in tackling crime and also in 900 its prevention and detection. 600 Some of the important factors impacting crime in Delhi are 300 the size and heterogeneous nature of its population; disparities in income; unemployment/ under employment, consumerism/ 0 materialism and socio-economic imbalances; unplanned 2016 2017 2018 urbanization with a substantial population living in jhuggi- jhopri/kachchi colonies and a nagging lack of civic amenities therein; proximity in location of colonies of the affluent and the under-privileged; impact of the mass media and the umpteen TOTAL IPC advertisements which sell a life-style that many want but cannot afford; a fast-paced life that breeds a general proclivity 250000 223077 236476 towards impatience; intolerance and high-handedness; urban 199107 anonymity and slack family control; easy accessibility/means 200000 of escape to criminal elements from across the borders/extended 150000 hinterland in the NCR region etc. -

Making Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross-Dressing in the Parsi Theatre Author(S): Kathryn Hansen Source: Theatre Journal, Vol

Making Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross-Dressing in the Parsi Theatre Author(s): Kathryn Hansen Source: Theatre Journal, Vol. 51, No. 2 (May, 1999), pp. 127-147 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25068647 Accessed: 13/06/2009 19:04 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=jhup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Theatre Journal. http://www.jstor.org Making Women Visible: Gender and Race Cross-Dressing in the Parsi Theatre Kathryn Hansen Over the last century the once-spurned female performer has been transformed into a ubiquitous emblem of Indian national culture. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Shakespeare in Gujarati: a Translation History

Shakespeare in Gujarati: A Translation History SUNIL SAGAR Abstract Translation history has emerged as one of the most significant enterprises within Translation Studies. Translation history in Gujarati per se is more or less an uncharted terrain. Exploring translation history pertaining to landmark authors such as Shakespeare and translation of his works into Gujarati could open up new vistas of research. It could also throw new light on the cultural and historical context and provide new insights. The paper proposes to investigate different aspects of translation history pertaining to Shakespeare’s plays into Gujarati spanning nearly 150 years. Keywords: Translation History, Methodology, Patronage, Poetics. Introduction As Anthony Pym rightly (1998: 01) said that the history of translation is “an important intercultural activity about which there is still much to learn”. This is why history of translation has emerged as one of the key areas of research all over the world. India has also taken cognizance of this and initiated efforts in this direction. Reputed organizations such as Indian Institute of Advanced Study (IIAS) and Central Institute of Indian Languages (CIIL) have initiated discussion and discourse on this area with their various initiatives. Translation history has been explored for some time now and it’s not a new area per se. However, there has been a paradigm shift in the way translation history is approached in the recent times. As Georges L. Bastin and Paul F. Bandia (2006: 11) argue in Charting the Future of Translation History: Translation Today, Volume 13, Issue 2 Sunil Sagar While much of the earlier work was descriptive, recounting events and historical facts, there has been a shift in recent years to research based on the interpretation of these events and facts, with the development of a methodology grounded in historiography.