Krzysztof Penderecki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

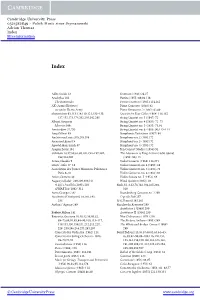

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Graå»Yna Bacewicz and Her Violin Compositions

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Gra#yna Bacewicz and Her Violin Compositions: From a Perspective of Music Performance Hui-Yun (Yi-Chen) Chung Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GRAŻYNA BACEWICZ AND HER VIOLIN COMPOSITIONS- FROM A PERSPECTIVE OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE By HUI-YUN (YI-CHEN) CHUNG A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 Hui‐Yun Chung defended this treatise on November 3, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eliot Chapo Professor Directing Treatise James Mathes University Representative Melanie Punter Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above‐named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my beloved family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deep gratitude and thanks to Professor Eliot Chapo for his support and guidance in the completion of my treatise. I also thank my committee members, Dr. James Mathes and Professor Melanie Punter, for their time, support and collective wisdom throughout this process. I would like to give special thanks to my previous violin teacher, Andrzej Grabiec, for his encouragement and inspiration. I wish to acknowledge my great debt to Dr. John Ho and Lucy Ho, whose kindly support plays a crucial role in my graduate study. I am grateful to Shih‐Ni Sun and Ming‐Shiow Huang for their warm‐hearted help. -

Premio Corso Salani 2015

il principale appuntamento italiano con il cinema dell’Europa centro orientale un progetto di Alpe Adria Cinema Alpe Adria Cinema 26a edizione piazza Duca degli Abruzzi 3 sala Tripcovich / teatro Miela 34132 Trieste / Italia 16-22 gennaio 2015 tel. +39 040 34 76 076 fax +39 040 66 23 38 [email protected] con il patrocinio di www.triesteflmfestival.it Comune di Trieste twitter.com/TriesteFilmFest Direzione Generale per il Cinema – facebook.com/TriesteFilmFest Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo con il contributo di Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia Creative Europe – MEDIA Programme CEI – Central European Initiative Provincia di Trieste Comune di Trieste Direzione Generale per il Cinema – Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo CCIAA – Camera di Commercio di Trieste con il sostegno di Lux Film Prize Istituto Polacco – Roma con la collaborazione di Fondazione Teatro Lirico Giuseppe Verdi – Trieste Fondo Audiovisivo FVG Associazione Casa del Cinema di Trieste La Cappella Underground FVG Film Commission Eye on Films Associazione Culturale Mattador Associazione Corso Salani Centro Ceco di Milano media partner mymovies.it media coverage by Sky Arte HD direzione artistica promozione, coordinamento volontari biglietteria Annamaria Percavassi e direzione di sala Rossella Mestroni, Alessandra Lama Fabrizio Grosoli Patrizia Pepi Gioffrè desk accrediti presidente comunicazione, progetto grafco Ambra De Nobili organizzazione generale immagine coordinata e allestimenti Cristina Sain Claimax -immagina.organizza.comunica- -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Symphony and Symphonic Thinking in Polish Music After 1956 Beata

Symphony and symphonic thinking in Polish music after 1956 Beata Boleslawska-Lewandowska UMI Number: U584419 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U584419 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signedf.............................................................................. (candidate) fa u e 2 o o f Date: Statement 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed:.*............................................................................. (candidate) 23> Date: Statement 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: ............................................................................. (candidate) J S liiwc Date:................................................................................. ABSTRACT This thesis aims to contribute to the exploration and understanding of the development of the symphony and symphonic thinking in Polish music in the second half of the twentieth century. -

Mahler's Klagende Lied

Mahler’s Klagende Lied SIMONE YOUNG’S VISIONS OF VIENNA 4 – 7 DECEMBER SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE CONCERT DIARY FEBRUARY 2020 The 1950s Latin Lounge Wed 5 Feb, 7pm Thu 6 Feb, 7pm Program includes: Sat 8 Feb, 7pm GERSHWIN Cuban Overture Sydney Town Hall MARQUEZ Danzón No.2 BERNSTEIN West Side Story – Mambo Guy Noble conductor Imogen Kelly dancer Ali McGregor soprano The Rite of Spring Symphony Hour Wed 19 Feb, 7pm RIOT AT THE BALLET Thu 20 Feb, 7pm WAGNER Die Meistersinger – Prelude Sydney Town Hall STRAVINSKY The Rite of Spring Pietari Inkinen conductor Abercrombie & Kent Debussy and Ravel Masters Series THE GREAT IMPRESSIONISTS Wed 26 Feb, 8pm RAVEL Piano Concerto in G Fri 28 Feb, 8pm MENDELSSOHN The Hebrides Sat 29 Feb, 8pm DEBUSSY La mer Thursday Afternoon Symphony Jun Märkl conductor Thu 27 Feb, 1.30pm Alexandra Dariescu piano Great Classics Sat 29 Feb, 2pm Sydney Town Hall MARCH 2020 Ben Folds Sydney Symphony Presents Fri 6 Mar, 8pm THE SYMPHONIC TOUR Sat 7 Mar, 8pm Pop icon and music innovator Ben Folds Sydney Town Hall returns to Sydney following his last sold- out shows with the Sydney Symphony. Ben Folds Nicholas Buc conductor Scheherazade Symphony Hour Wed 11 Mar, 7pm HYPNOTIC AND SUBLIME Thu 12 Mar, 7pm DEBUSSY Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun Tea & Symphony RIMSKY-KORSAKOV Scheherazade Fri 13 Mar, 11am Alexander Shelley conductor Sydney Town Hall Debussy, Mozart and Rimsky-Korsakov Emirates Metro Series Fri 13 Mar, 8pm SENSE AND SENSUALITY Sydney Town Hall DEBUSSY Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun MOZART Sinfonia Concertante, K.364 RIMSKY-KORSAKOV Scheherazade Alexander Shelley conductor Harry Bennetts violin Tobias Breider viola Abercrombie & Kent Beethoven Missa Solemnis Masters Series MUSIC OF INSPIRATION Wed 18 Mar, 8pm BEETHOVEN Missa Solemnis Fri 20 Mar, 8pm Sat 21 Mar, 8pm Donald Runnicles conductor Siobhan Stagg soprano Sydney Town Hall Vasilisa Berzhanskaya mezzo-soprano Samuel Sakker tenor Derek Welton bass Sydney Philharmonia Choirs Cats 240x150.indd 1 2/9/19 16:40 WELCOME Welcome to the Abercrombie & Kent Masters Series. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

SYDNEY SYMPHONY UNDER the STARS BENJAMIN NORTHEY DIANA DOHERTY CONDUCTOR OBOE Principal Oboe, John C Conde AO Chair

SYDNEY SYMPHONY Photo: Photo: Jamie Williams UNDER THE STARS SYDNEY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA I AUSTRALIA PROGRAM Dmitri Shostakovich (Russian, 1906–1975) SYDNEY Festive Overture SYMPHONY John Williams (American, born 1932) Hedwig’s Theme from Harry Potter UNDER THE Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Austrian, 1756–1791) Finale from the Horn Concerto No.4, K.495 STARS Ben Jacks, horn SYDNEY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA I AUSTRALIA THE CRESCENT Hua Yanjun (Chinese, 1893–1950) PARRAMATTA PARK Reflection of the Moon on the Lake at Erquan 8PM, 19 JANUARY 120 MINS John Williams Highlights from Star Wars: Imperial March Benjamin Northey conductor Cantina Music Diana Doherty oboe Main Title Ben Jacks horn INTERVAL Sydney Symphony Orchestra Gioachino Rossini (Italian, 1792–1868) Galop (aka the Lone Ranger Theme) from the overture to the opera William Tell Percy Grainger (Australian, 1882–1961) The Nightingale and the Two Sisters from the Danish Folk-Song Suite Edvard Grieg (Norwegian, 1843–1907) Highlights from music for Ibsen’s play Peer Gynt: Morning Mood Anitra’s Dance In the Hall of the Mountain King Ennio Morricone (Italian, born 1928) Theme from The Mission Diana Doherty, oboe Josef Strauss (Austrian, 1827–1870) Music of the Spheres – Waltz Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian, 1840–1893) 1812 – Festival Overture SYDNEYSYDNEY SYMPHONY SYMPHONY UNDER UNDER THE STARS THE STARS SYDNEY SYMPHONY UNDER THE STARS BENJAMIN NORTHEY DIANA DOHERTY CONDUCTOR OBOE Principal Oboe, John C Conde AO Chair Benjamin Northey is Chief Conductor of the Christchurch Diana Doherty joined the Sydney Symphony Orchestra as Symphony Orchestra and Associate Conductor of the Principal Oboe in 1997, having held the same position with Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. -

Kunstbericht 2011 Kunstbericht

Kunstbericht-2011-FX.indd 1 Kunstbericht 2011 Kunstbericht 06.06.12 08:14 2011 Kunstbericht 2011 Bericht über die Kunstförderung des Bundes Struktur der Ausgaben Förderungen im Detail Service Glossar zur Kunstförderung Impressum Herausgeber Bundesministerium für Unterricht, Kunst und Kultur, Kunstsektion, 1010 Wien, Minoritenplatz 5 Redaktion Alexandra Auth, Herbert Hofreither, Robert Stocker Cover Christina Brandauer Grafische Gestaltung, Satz, Herstellung Peter Sachartschenko Herstellung Druckerei Berger, Horn Inhalt Vorwort Seite 5 I Struktur der Ausgaben Seite 7 II Förderungen im Detail Seite 81 III Service Seite 139 IV Glossar zur Kunstförderung Seite 263 V Register Seite 297 Kunstbericht 2011 5 Vorwort Der Kunstbericht 2011 ist mehr als nur ein Geschäftsbericht. Er stellt nicht nur transpa- rent Zahlen und Fakten dar, er zeigt vor allem die Bandbreite der Kunstförderung und den Erfolg des künstlerischen Schaffens in der Literatur, am Theater, in der Musik, im Film, in der bildenden Kunst sowie die Arbeit der regionalen Kulturinstitutionen. Gemeinsam können wir auf ein gutes Jahr für die Kunst zurückblicken: nationale und internationale Preise für den österreichischen Film, die Umsetzung der Kinodigitalisie- rung für die Programmkinos, ein vielbeachteter Beitrag Österreichs bei der Kunstbiennale in Venedig, weitere Stärkung des zeitgenössischen Kunstschaffens und die nachhaltige © Hans Ringhofer Umsetzung der Nachwuchsförderung und Kulturvermittlung. Um eine kontinuierliche Tätigkeit zu ermöglichen, bedarf es eines stabilen Budgets. Trotz der Konsolidierung des Staatshaushaltes, die zu Kürzungen in einigen Ressorts geführt hat, ist es uns im Bereich der Kunst und Kultur gelungen, die Budgets und die Ausgaben stabil zu halten. Darin drückt sich das klare Bekenntnis zur Verantwortung des Staates für die Förderung von Kunst aus. -

Compassion Booklet

481 0678 Compassion – Symphony of Songs Song cycle for voice and orchestra by Lior and Nigel Westlake based on a collection of ancient Hebrew and Arabic texts 1 Sim Shalom – Grant Peace 7’28 2 Eize Hu Chacham? – Who is Wise? 5’25 3 La Yu’minu – Until You Love Your Brother 4’18 4 Inna Rifqa – The Beauty Within 4’55 5 Al Takshu L’vavchem – Don’t Harden Your Hearts 4’45 6 Ma Wadani Ahadun – Until the End of Time 7’57 7 Avinu Malkeinu – Hymn of Compassion 5’57 Total Playing Time 40’46 Lior vocals Sydney Symphony Orchestra Nigel Westlake conductor Compassion was commissioned by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, for the SSO and the other Australian symphony orchestras, with the support of Symphony Services International. 3 The Genesis of Compassion In stark contrast to what had preceded, here was another side to Lior’s artistry, his keening and emotionally charged voice allowing us an intimate glimpse into the rich vein of middle eastern heritage The catalyst for Compassion can be traced to a single watershed moment: the occurrence of my first that is his birthright. Lior concert. It was the winter of 2009 in the tiny rural village of St Albans NSW, the occasion being the inaugural fundraising event for the Smugglers of Light, a foundation formed by our family in The power and spirituality of the song struck a deep resonance amongst the crowd, all of whom were memory of my son Eli. captivated in spellbound rapture. For my own part, I had just experienced a small taste of a tantalising and exotic sound world and was overcome by a strange yearning to be a part of it. -

NSF Programme Book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 1

two weeks of world-class music newbury spring festival 11–25 may 2019 £5 2019-NSF book.qxp_NSF programme book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 1 A Royal Welcome HRH The Duke of Kent KG Last year was very special for the Newbury Spring Festival as we marked the fortieth anniversary of the Festival. But following this anniversary there is some sad news, with the recent passing of our President, Jeanie, Countess of Carnarvon. Her energy, commitment and enthusiasm from the outset and throughout the evolution of the Festival have been fundamental to its success. The Duchess of Kent and I have seen the Festival grow from humble beginnings to an internationally renowned arts festival, having faced and overcome many obstacles along the way. Jeanie, Countess of Carnarvon, can be justly proud of the Festival’s achievements. Her legacy must surely be a Festival that continues to flourish as we embark on the next forty years. www.newburyspringfestival.org.uk 1 2019-NSF book.qxp_NSF programme book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 2 Jeanie, Countess of Carnarvon MBE Founder and President 1935 - 2019 2 box office 0845 5218 218 2019-NSF book.qxp_NSF programme book 23/04/2019 12:31 Page 3 The Festival’s founder and president, Jeanie Countess of Carnarvon was a great and much loved lady who we will always remember for her inspirational support of Newbury Spring Festival and her gentle and gracious presence at so many events over the years. Her son Lord Carnarvon pays tribute to her with the following words. My darling mother’s lifelong interest in the arts and music started in her childhood in the USA. -

Philharmonic Hall Lincoln Center F O R T H E Performing Arts

PHILHARMONIC HALL LINCOLN CENTER F O R T H E PERFORMING ARTS 1968-1969 MARQUEE The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center is Formed A new PERFORMiNG-arts institution, The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, will begin its first season of con certs next October with a subscription season of 16 concerts in eight pairs, run ning through early April. The estab lishment of a chamber music society completes the full spectrum of perform ing arts that was fundamental to the original concept of Lincoln Center. The Chamber Music Society of Lin coln Center will have as its home the Center’s new Alice Tully Hall. This intimate hall, though located within the new Juilliard building, will be managed by Lincoln Center as an independent Wadsworth Carmirelli Treger public auditorium, with its own entrance and box office on Broadway between 65th and 66th Streets. The hall, with its 1,100 capacity and paneled basswood walls, has been specifically designed for chamber music and recitals. The initial Board of Directors of the New Chamber Music Society will com prise Miss Alice Tully, Chairman; Frank E. Taplin, President; Edward R. Ward well, Vice-President; David Rockefeller, Jr., Treasurer; Sampson R. Field, Sec retary; Mrs. George A. Carden; Dr. Peter Goldmark; Mrs. William Rosen- wald and Dr. William Schuman. The Chamber Music Society is being organ ized on a non-profit basis and, like other cultural institutions, depends upon voluntary contributions for its existence. Charles Wadsworth has been ap pointed Artistic Director of The Cham ber Music Society of Lincoln Center. The Society is the outgrowth of an in tensive survey of the chamber music field and the New York chamber music audience, conducted by Mr.