Deaf Jam Discussion Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FRI. AUGUST 2 6:00 P.M., Free Unnameable Books 600 Vanderbilt

MUSIC Bird To Prey, Major Matt Mason USA POETRY Becca Klaver, BOOG CITY Megan McShea, Mike Topp A COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER FROM A GROUP OF ARTISTS AND WRITERS BASED IN AND AROUND NEW YORK CITY’S EAST VILLAGE ISSUE 82 FREE Jonathan Allen art Creative Writing from Columbia University and her M.F.A. in band that will be debuting its first material this fall. But until instructor and consultant. Her poetry has appeared or FRI. AUGUST 2 poetry from NYU. Her work has been featured or is forthcoming then he finds himself in a nostalgic summer detour, in New York is forthcoming in 1913; No, Dear magazine; Two Serious 6:00 P.M., Free in numerous publications, including Forklift, once again, home once again. Christina Coobatis photo. Ladies; Wag’s Revue; and elsewhere. Her chapbook, Russian Ohio; Painted Bride Quarterly; PANK; Vinyl • for Lovers, was published by Argos Books. She lives in Unnameable Books Poetry; and the anthology Why I Am Not His Creepster Freakster is one of those albums that Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn and works as an adjunct A Painter, published by Argos Books. She just absorbs you and spits you out. But his later work with instructor. Luke Bumgarner photo. 600 Vanderbilt Ave. was a finalist this year for The Poetry Supernatural Christians and Injecting Strangers is taking it (bet. Prospect Place/St. Marks Avenue) Project’s Emerge-Surface-Be Fellowship. A all further. He is the nicest, sweetest, politest, most merciless Sarah Jeanne Peters 7:55 p.m. Prospect Heights, Cave Canem fellow, Parker lives with her dog Braeburn in artist you will ever come across. -

Hohonu Volume 5 (PDF)

HOHONU 2007 VOLUME 5 A JOURNAL OF ACADEMIC WRITING This publication is available in alternate format upon request. TheUniversity of Hawai‘i is an Equal Opportunity Affirmative Action Institution. VOLUME 5 Hohonu 2 0 0 7 Academic Journal University of Hawai‘i at Hilo • Hawai‘i Community College Hohonu is publication funded by University of Hawai‘i at Hilo and Hawai‘i Community College student fees. All production and printing costs are administered by: University of Hawai‘i at Hilo/Hawai‘i Community College Board of Student Publications 200 W. Kawili Street Hilo, Hawai‘i 96720-4091 Phone: (808) 933-8823 Web: www.uhh.hawaii.edu/campuscenter/bosp All rights revert to the witers upon publication. All requests for reproduction and other propositions should be directed to writers. ii d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d d Table of Contents 1............................ A Fish in the Hand is Worth Two on the Net: Don’t Make me Think…different, by Piper Seldon 4..............................................................................................Abortion: Murder-Or Removal of Tissue?, by Dane Inouye 9...............................An Etymology of Four English Words, with Reference to both Grimm’s Law and Verner’s Law by Piper Seldon 11................................Artifacts and Native Burial Rights: Where do We Draw the Line?, by Jacqueline Van Blarcon 14..........................................................................................Ayahuasca: Earth’s Wisdom Revealed, by Jennifer Francisco 16......................................Beak of the Fish: What Cichlid Flocks Reveal About Speciation Processes, by Holly Jessop 26................................................................................. Climatic Effects of the 1815 Eruption of Tambora, by Jacob Smith 33...........................Columnar Joints: An Examination of Features, Formation and Cooling Models, by Mary Mathis 36.................... -

Firm Background Information

1215 Hamilton Lane, Suite 200 Naperville, IL 60540 Moran Technology Consulting (MTC) is an experienced and proven provider of consulting services to the Higher Education, K-12 and public-sector industries. MTC offers a full range of IT and management consulting services to our clients. Our consultants have worked with over 240 institutions and have conducted over 590 projects. We work hard for our clients. We have focused our resources in several key areas: • ERP Transformation, Planning and Oversight: We have led projects to help clients plan for the impact that a new ERP system can have on an institution (organization, technology, processes, and culture). We approach these projects as a multi-phased effort: Establish Transformation Guidelines to define how the school wants to run its business processes in the future; Utilize Process Transformation / Improvement to provide the details on how the processes should be performed; Develop a Product Deployment strategy and support; and Plan for Post-Installation support. These same tools have also proven highly successful in helping institutions drive services improvements within existing ERP environments. • Product/Package Selection and Acquisition Support: We have led projects for clients in all phases of selecting and acquiring a new product or software package and the associated consulting services. We have done engagements for many products/technologies, including: VoIP, ERP, SIS, Finance, HCM, LMS, CRM, SaaS based and on-premises based and many others. We approach these projects as a multi-phased effort: Requirement Definition to define the RFP requirements to meet the institutions needs and to support the new business processes; RFP Development to help clients write the detailed RFP specification needed to select a vendor; and RFP Support to help clients through the vendor selection and contract negotiations processes. -

2007 Tuskegee Symposium Program

HBCU Faculty Development Network Conference Program http://hbcufdn.org Fourteenth National HBCU Faculty Development Symposium “Enhancing Quality through Engaged Assessment & Research” October 18-20, 2007 Kellogg Hotel and Conference Center Tuskegee University Tuskegee, Alabama ♦ Sponsored by HBCU Faculty Development Network ♦ Co-hosted by Tuskegee University & Alabama State University ♦ Fourteenth National HBCU Faculty Development Symposium “Enhancing Quality through Engaged Assessment & Research” October 18-20, 2007 Kellogg Hotel and Conference Center Tuskegee University Tuskegee, Alabama ♦ October 18, 2007 STEERING COMMITTEE Hasan Crockett Dear Colleague: Morehouse College This Fourteenth National HBCU Faculty Development Symposium on Phyllis Worthy Dawkins Johnson C. Smith University “Enhancing Quality through Engaged Assessment & Research” places focus on the importance of examining the outcomes of our instructional strategies to Henry J. Findlay Tuskegee University develop the most effective approaches for enhancing teaching and learning, and also for meeting the growing demands of accreditation organizations and grant Laurette B. Foster Prairie View A&M University funders. Eugene Hermitte Bringing the HBCU Faculty Development Symposium to Tuskegee gives us Johnson C. Smith University the opportunity to visit an institution that is rich in history and that serves as a M. Shelly Hunter symbol of the ongoing struggle for equal rights and justice. We will also be Norfolk State University focusing on nearby Montgomery with our visit to Alabama State University and Stephen L. Rozman the showing of a documentary film on the women behind the Montgomery Bus Tougaloo College Boycott, followed by a panel discussion. Emeritus We welcome as keynote speaker Dr. Vincent Tinto, a national leader in the Joyce P. Peoples Atlanta Metropolitan College use of learning communities and collaborative pedagogies to enhance student learning and retention. -

Idaho School for the Deaf and the Blind

Idaho School for the Deaf and the Blind Evaluation Report October 2005 Office of Performance Evaluations Idaho Legislature Report 05-03 Created in 1994, the Legislative Office of Performance Evaluations operates under the authority of Idaho Code § 67-457 through 67-464. Its mission is to promote confidence and accountability in state government through professional and independent assessment of state agencies and activities, consistent with Legislative intent. The eight-member, bipartisan Joint Legislative Oversight Committee approves evaluation topics and receives completed reports. Evaluations are conducted by Office of Performance Evaluations staff. The findings, conclusions, and recommendations in the reports do not necessarily reflect the views of the committee or its individual members. Joint Legislative Oversight Committee Senate House of Representatives Shawn Keough, Co-chair Margaret Henbest, Co-chair John C. Andreason Maxine T. Bell Bert C. Marley Debbie S. Field Kate Kelly Donna Boe Rakesh Mohan, Director Office of Performance Evaluations Idaho School for the Deaf and the Blind October 2005 Report 05-03 Office of Performance Evaluations 700 W. State Street, Lower Level, Suite 10 P.O. Box 83720, Boise, Idaho 83720-0055 Office of Performance Evaluations ii Office of Performance Evaluations iv Idaho School for the Deaf and the Blind Table of Contents Page Executive Summary............................................................................................................ ix Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................................... -

Administration

Smart & Sustainable Campuses Conference 2008 Organizations that sent attendees AASHE Academic Privatization, LLC /AP Management Company, LLC Affiliated Engineers, Inc. Amenta/Emma Architects Amherst College APPA Appalachian State University Aquinas College ARAMARK Higher Education Arcadia University Archibus Arizona State University ASG, Inc. Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education Atlantic Information Services Ayers Saint Gross, Architects & Planners Barton Malow Company Bentley University Berea College Biohabitats, Inc. BLT Architects Bowie State University Brown University Bucknell University Burt Hill Kosar Rittelmann Associates California State University, East Bay California State University, Fresno California State University, Monterey Bay Campus Consortium for Environmental Excellence Cannon Design Case Western Reserve University Castleton State College Cedar Valley College Central Michigan University Chatham University Chesapeake Climate Action Network Chestnut Hill College Chevron Energy Solutions Christchurch School Clark University Clean Air-Cool Planet College of William and Mary Colorado Academy Colorado College Community Energy, Inc Connecticut College Coppin State University Creative Artists Agency Cubellis Culver Academies Cunningham + Quill Architects, PLLC CUNY Herbert H. Lehman College Smart & Sustainable Campuses Conference 2008 Organizations that sent attendees CUNY The City College of New York Davidson County Community College Design Collective, Inc. Dickinson College Dining Services -

2021-02-12 FY2021 Grant List by Region.Xlsx

New York State Council on the Arts ‐ FY2021 New Grant Awards Region Grantee Base County Program Category Project Title Grant Amount Western New African Cultural Center of Special Arts Erie General Support General $49,500 York Buffalo, Inc. Services Western New Experimental Project Residency: Alfred University Allegany Visual Arts Workspace $15,000 York Visual Arts Western New Alleyway Theatre, Inc. Erie Theatre General Support General Operating Support $8,000 York Western New Special Arts Instruction and Art Studio of WNY, Inc. Erie Jump Start $13,000 York Services Training Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie General Support ASI General Operating Support $49,500 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Arts Services Initiative of State & Local Erie Regrants ASI SLP Decentralization $175,000 York Western NY, Inc. Partnership Western New Buffalo and Erie County Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Historical Society Western New Buffalo Arts and Technology Community‐Based BCAT Youth Arts Summer Program Erie Arts Education $10,000 York Center Inc. Learning 2021 Western New BUFFALO INNER CITY BALLET Special Arts Erie General Support SAS $20,000 York CO Services Western New BUFFALO INTERNATIONAL Electronic Media & Film Festivals and Erie Buffalo International Film Festival $12,000 York FILM FESTIVAL, INC. Film Screenings Western New Buffalo Opera Unlimited Inc Erie Music Project Support 2021 Season $15,000 York Western New Buffalo Society of Natural Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $20,000 York Sciences Western New Burchfield Penney Art Center Erie Museum General Support General Operating Support $35,000 York Western New Camerta di Sant'Antonio Chamber Camerata Buffalo, Inc. -

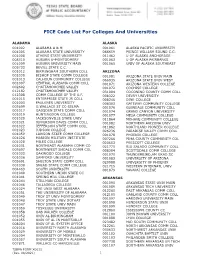

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

February 26, 2021 President, Search Committee New College of Florida

February 26, 2021 President, Search Committee New College of Florida Via Electronic Mail Dear Members of the Search Committee: As I read your engaging presidential prospectus, I was drawn to New College of Florida’s distinctive liberal arts model. The opportunity to expand on the college’s influence and build on this unique model that is “open-minded, minimally prescriptive, customized, and evolutionary” invigorates me. Each time I read it I feel myself gaining energy and purpose. I enthusiastically submit my “curriculum vitae,” highlighting a cutting edge integration of applied liberal arts, the intersection of career development and education, an inclusive and welcoming community that builds trust, enhanced organizational effectiveness, and successful financial leadership with partnerships and fundraising. My qualifications and experiences prepare me particularly well to help build an increasingly visible role for New College of Florida that draws interest and enrollment from new pools of students throughout the state, region, nation and world. When I first enrolled at Trinity College in Hartford, CT, as an undergraduate, I encountered faculty who were ready and eager to mentor and guide me. One example is Dori Katz, my faculty advisor, who did not tell me that majoring in French would be impossible because I am deaf. She said, "I will help you." But I soon learned that she didn't know how. So I began to teach her about my world, as she taught me about hers. Without the discussion we sustained and the careful attention she gave me over four years, I may never have become the educated, ethical and engaged citizen that I am today. -

Summer Books Issue the TEXAS

Summer Books Issue THE TEXAS A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES JULY 31, 1998 • $2.25 Bob Sherrill on Poppy Bush Don Graham on Cormac's Trilogy Plus an Excerpt of Gary Webb's Dark Alliance THIS ISSUE FEATURE Dark Alliance by Gary Webb 10 How a trail of money, politics, and drugs lead one reporter into the CIA and the Reagan White House DEPARTMENTS Deep-Dish, Hold the Rhyme 21 Dialogue 2 Poetry by Bob Holman Editorial Latina Lit 22 Contra Contratemps 4 Poetry Review by Dave Oliphant by Louis Dubose VOLUME 90, NO. 14 Elroy Bode's Texas 24 Book Review by Richard Phelan A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES BOOKS AND THE CULTURE We will serve no group or party but will hew hard to the truth as we find it and the right as we see it. We are Cormac McCarthy's Border 5 Police Story 27 dedicated to the whole truth, to human values above all interests, to the rights of human-kind as the foundation Book Review by Don Graham Book Review by Steven G. Kellman of democracy: we will take orders from none but our own conscience, and never will we overlook or misrep- The Banal Mr. Bush 8 Blue-Collar Conquistador 29 resent the truth to serve the interests of the powerful or cater to the ignoble in the human spirit. Book Review by Robert Sherrill Book Review by Pat LittleDog Writers are responsible for their own work, but not for anything they have not themselves written, and in Afterword 30 publishing them we do not necessarily imply that we The State of Swing 16 agree with them, because this is a journal of free voices. -

Segue Reading Series @ Bowery Poetry Club

SEGUE READING SERIES @ BOWERY POETRY CLUB Saturdays: 4:00 p.m. - 6:00 p.m. 308 BOWERY, just north of Houston ****$5 admission goes to support the readers**** Fall / Winter 2006-2007 These events are made possible, in part, with public funds from The New York State Council on the Arts, a state agency. The Segue Reading Series is made possible by the support of The Segue Foundation. For more information, please visit www.segue.org, bowerypoetry.com/midsection.htm, or call (212) 614-0505. Curators: Oct.-Nov. by Nada Gordon & Gary Sullivan, Dec.-Jan. by Brenda Iijima & Evelyn Reilly. OCTOBER OCTOBER 7 STAN APPS and KIM ROSENFIELD Stan Apps is a poet from Los Angeles, author of a chapbook of poetry, soft hands, from Ugly Duckling Presse, and of an upcoming full-length collection, Info Ration from Make Now Press. Stan enjoys blogging and co-curating the Last Sunday of the Month reading series at the smell in L.A. Stan is originally from Waco, Texas, and is a typical touchy- feely liberal cult-member, currently allied with the cult called Flarf. Stan is also co- editing a new chapbook press called Insert Press. Kim Rosenfield is the author of several books of poetry including Trama, Good Morning: Midnight, Rx and Cool Clean Chemistry, and Some of Us. Her work has appeared in numerous magazines and journals including Object, Shiny, Torque, Crayon, and Chain. She lives and works in New York City. OCTOBER 14 SHANNA COMPTON and MICHAEL MAGEE Shanna Compton is the author of Down Spooky, a collection of poems published by Winnow Press in 2005, and the editor of GAMERS: Writers, Artists & Programmers on the Pleasures of Pixels, an anthology of essays on the theme of video games published by Soft Skull Press in 2004. -

Download CV (Pdf)

RAQUEL ALMAZAN RAQUEL.ALMAZAN@ COLUMBIA.EDU WWW.RAQUELALMAZAN.COM SUMMARY Raquel Almazan is an actor, writer, director in professional theatre / film / television productions. Her eclectic career as artist-activist spans original multi- media solo performances, playwriting, new work development and dramaturgy. She is a practitioner of Butoh Dance and creator/teacher of social justice arts programs for youth/adults, several focusing on social justice. Her work has been featured in New York City- including Off-Broadway, throughout the United States and internationally in Greece, Italy, Slovenia, Colombia, Chile, Guatemala, Canada and Sweden; including plays within her lifelong project on writing bi-lingual plays in dedication to each Latin American country (Latin is America play cycle). EDUCATION MFA Playwriting, School of the Arts Columbia University, New York City BFA Theatre Performance/Playwriting University of Florida-New World School of With honors the Arts Conservatory, Miami, Florida AA Film Directing Miami Dade College, Miami Florida PLAYWRITING – Columbia University Playwriting through aesthetics/ Playwriting Projects: Charles Mee Play structure and analysis/Playwriting Projects: Kelly Stuart Thesis and Professional Development: David Henry Hwang and Chay Yew American Spectacle: Lynn Nottage Political Theatre/Dramaturgy: Morgan Jenness Collaboration Class- Mentored by Ken Rus Schmoll Adaptation: Anthony Weigh New World SAC Master Classes Excerpt readings and feedback on Blood Bits and Junkyard Food plays: Edward Albee Writing