Gregoryh.Pdf (PDF, 1.334Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FRI. AUGUST 2 6:00 P.M., Free Unnameable Books 600 Vanderbilt

MUSIC Bird To Prey, Major Matt Mason USA POETRY Becca Klaver, BOOG CITY Megan McShea, Mike Topp A COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER FROM A GROUP OF ARTISTS AND WRITERS BASED IN AND AROUND NEW YORK CITY’S EAST VILLAGE ISSUE 82 FREE Jonathan Allen art Creative Writing from Columbia University and her M.F.A. in band that will be debuting its first material this fall. But until instructor and consultant. Her poetry has appeared or FRI. AUGUST 2 poetry from NYU. Her work has been featured or is forthcoming then he finds himself in a nostalgic summer detour, in New York is forthcoming in 1913; No, Dear magazine; Two Serious 6:00 P.M., Free in numerous publications, including Forklift, once again, home once again. Christina Coobatis photo. Ladies; Wag’s Revue; and elsewhere. Her chapbook, Russian Ohio; Painted Bride Quarterly; PANK; Vinyl • for Lovers, was published by Argos Books. She lives in Unnameable Books Poetry; and the anthology Why I Am Not His Creepster Freakster is one of those albums that Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn and works as an adjunct A Painter, published by Argos Books. She just absorbs you and spits you out. But his later work with instructor. Luke Bumgarner photo. 600 Vanderbilt Ave. was a finalist this year for The Poetry Supernatural Christians and Injecting Strangers is taking it (bet. Prospect Place/St. Marks Avenue) Project’s Emerge-Surface-Be Fellowship. A all further. He is the nicest, sweetest, politest, most merciless Sarah Jeanne Peters 7:55 p.m. Prospect Heights, Cave Canem fellow, Parker lives with her dog Braeburn in artist you will ever come across. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS General enquiries [email protected] Alice Dewing FREELANCE [email protected] Anna Pallai Amy Canavan [email protected] [email protected] Caitlin Allen Camilla Elworthy [email protected] [email protected] Elinor Fewster Emma Bravo [email protected] [email protected] Emma Draude Gabriela Quattromini [email protected] [email protected] Emma Harrow Grace Harrison [email protected] [email protected] Jacqui Graham Hannah Corbett [email protected] [email protected] Jamie-Lee Nardone Hope Ndaba [email protected] [email protected] Laura Sherlock Jess Duffy [email protected] [email protected] Ruth Cairns Kate Green [email protected] [email protected] Philippa McEwan [email protected] Rosie Wilson [email protected] Siobhan Slattery [email protected] CONTENTS MACMILLAN PAN MANTLE TOR PICADOR MACMILLAN COLLECTOR’S LIBRARY BLUEBIRD ONE BOAT MACMILLAN Nine Lives Danielle Steel Nine Lives is a powerful love story by the world’s favourite storyteller, Danielle Steel. Nine Lives is a thought-provoking story of lost love and new beginnings, by the number one bestseller Danielle Steel. After a carefree childhood, Maggie Kelly came of age in the shadow of grief. Her father, a pilot, died when she was nine. Maggie saw her mother struggle to put their lives back together. As the family moved from one city to the next, her mother warned her about daredevil men and to avoid risk at all cost. Following her mother’s advice, and forgoing the magic of first love with a high-school boyfriend who she thought too wild, Maggie married a good, dependable man. -

I Wanna Be Yours - John Cooper Clarke

Edexcel English Literature GCSE Poetry Collection: Relationships i wanna be yours - John Cooper Clarke This work by PMThttps://bit.ly/pmt-edu-cc Education is licensed under https://bit.ly/pmt-ccCC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://bit.ly/pmt-cc https://bit.ly/pmt-edu https://bit.ly/pmt-cc I WANNA BE YOURS John Cooper Clarke Brief Summary The poem features an unknown speaker addressing their lover, who is also unknown to the reader. The speaker asks to be let into every aspect of their lover’s life by listing the different mundane, everyday objects they want to replace. As well as asking to be needed and adored by their lover, the speaker demonstrates their devotion to their lover and the consistency of their affection. The exact relationship between the speaker and the object of their affection is unknown, but it is clear that the speaker wants to be closer to the person they are addressing. The poem is full of simplistic language, word play, and innuendo. Synopsis ● The speaker is talking directly to an unknown subject and we never hear their response to the speaker ● The speaker asks their lover if they will “let” them take the place of various everyday objects in their life ● The speaker makes it clear that their lover is in control ● The only thing the speaker desires is to belong to their lover ● The list of mundane objects continues as the speaker makes it clear that they want to make their lover’s life better and be with them everywhere ● The final stanza finishes with a grander, more metaphysical (deep) image than the mundane objects previously used to show the extent of the speaker’s devotion ● The speaker concludes by clarifying they want no one else other than the lover they are addressing in this poem Context John Cooper Clarke (1949 - present) John Cooper Clarke was born in Salford, Lancashire, in the north of England. -

SUMMER 2016 Www

Box Office 0504 90204 SUMMER 2016 www.thesourceartscentre.ie www. thesourceartscentre.ie The Source Arts Centre Summer 2016 Programme The days are finally getting brighter and a little warmer so it’s a good time to get out of the house and come to the Source to see a few events. We’ve got a good selection of musical acts – the highly tipped Dublin songwriter Anderson who became famous for selling his album door-to-door, arrives for a solo show; Cork-born songwriter Mick Flannery presents his new album in another solo gig and we’ve opened up the auditorium for some tribute shows like Live Forever and Roadhouse Doors to give a more concert-type feel, so check these out on our brochure. Legendary Manchester poet John Cooper Clarke comes to visit us on May 4th; we have theatre with ‘The Corner Boys’, God Bless The Child’ and Brendan Balfe reminisces about the golden days of Irish radio in early June. Summer is a time for the kids and again we have a series of arts workshops and classes running over the summer months to keep them all occupied. Keep a lookout for our website: www.thesourceartscentre.ie for updates to our programme as we regularly add new events. Addtionally we put updates on our Facebook page. If you wish to be included on our mailing list, just get in contact with us at: boxoffice @sourcearts.ie We look forward to seeing you at The Source during the summer Brendan Maher Artistic Director Buy online Stef Hans open at You can choose your preferred seat when you The Source Arts Centre buy online 24/7 via your laptop, tablet or smart Fine day-time cuisine from award winning phone at www.thesourceartscentre.ie. -

Summer Books Issue the TEXAS

Summer Books Issue THE TEXAS A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES JULY 31, 1998 • $2.25 Bob Sherrill on Poppy Bush Don Graham on Cormac's Trilogy Plus an Excerpt of Gary Webb's Dark Alliance THIS ISSUE FEATURE Dark Alliance by Gary Webb 10 How a trail of money, politics, and drugs lead one reporter into the CIA and the Reagan White House DEPARTMENTS Deep-Dish, Hold the Rhyme 21 Dialogue 2 Poetry by Bob Holman Editorial Latina Lit 22 Contra Contratemps 4 Poetry Review by Dave Oliphant by Louis Dubose VOLUME 90, NO. 14 Elroy Bode's Texas 24 Book Review by Richard Phelan A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES BOOKS AND THE CULTURE We will serve no group or party but will hew hard to the truth as we find it and the right as we see it. We are Cormac McCarthy's Border 5 Police Story 27 dedicated to the whole truth, to human values above all interests, to the rights of human-kind as the foundation Book Review by Don Graham Book Review by Steven G. Kellman of democracy: we will take orders from none but our own conscience, and never will we overlook or misrep- The Banal Mr. Bush 8 Blue-Collar Conquistador 29 resent the truth to serve the interests of the powerful or cater to the ignoble in the human spirit. Book Review by Robert Sherrill Book Review by Pat LittleDog Writers are responsible for their own work, but not for anything they have not themselves written, and in Afterword 30 publishing them we do not necessarily imply that we The State of Swing 16 agree with them, because this is a journal of free voices. -

Art, Identity, and Status in UK Poetry Slam

Oral Tradition, 23/2 (2008): 201-217 (Re)presenting Ourselves: Art, Identity, and Status in U.K. Poetry Slam Helen Gregory Introducing Poetry Slam Poetry slam is a movement, a philosophy, a form, a genre, a game, a community, an educational device, a career path, and a gimmick. It is a multi-faced creature that means many different things to many different people. At its simplest, slam is an oral poetry competition in which poets are expected to perform their own work in front of an audience. They are then scored on the quality of their writing and performance by judges who are typically randomly selected members of the audience. The story of slam reaches across more than two decades and thousands of miles. In 1986, at the helm of “The Chicago Poetry Ensemble,” Marc Smith organized the first official poetry slam at the Green Mill in Chicago under the name of the Uptown Poetry Slam (Heintz 2006; Smith 2004). This weekly event still continues today and the Uptown Poetry Slam has become a place of pilgrimage for slam poets from across the United States and indeed the world. While it parallels poetry in remaining a somewhat marginal activity, slam has arguably become the most successful poetry movement of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Its popularity is greatest in its home country, where the annual National Poetry Slam (NPS) can attract audiences in the thousands and where it has spawned shows on television and on Broadway. Beyond this, slam has spread across the globe to countries as geographically and culturally diverse as Australia, Singapore, South Africa, Poland, and the U.K. -

Warwickshire Cover

Worcestershire Cover Online.qxp_Birmingham Cover 29/07/2016 10:58 Page 1 Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands ISSUE 368 AUGUST 2016 JIMMY OSMOND Worcestershire OUT ON NEW UK TOUR ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On worcestershirewhatson.co.uk inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide PRESENT LAUGHTER NOËL COWARD’S COMEDY ARRIVES AT MALVERN THEATRES Donington F/P - August '16.qxp_Layout 1 25/07/2016 10:08 Page 1 Contents August Warwickshire/Worcs.qxp_Layout 1 25/07/2016 12:09 Page 1 August 2016 Contents The Rover - Aphra Behn’s play returns to the Swan Theatre. Feature page 8 Julian Marley Sir Antony Sher Spectacular Science the list Reggae superstar embarks on Award-winning actor takes on Brand new show to dispel Your 16-page his first ever UK tour King Lear at the RSC ‘science is boring’ myth... week-by-week listings guide page 14 page 30 page 26 page 51 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 14. Music 26. Comedy 28. Theatre 37. Film 40. Visual Arts 43. Events fb.com/whatsonwarwickshire fb.com/whatsonworcestershire @whatsonwarwicks @whatsonworcs Warwickshire What’s On Magazine Worcestershire What’s On Magazine Warwickshire What’s On Magazine Worcestershire What’s On Magazine Managing Director: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 ’ Sales & Marketing: Matt Rothwell [email protected] 01743 281719 Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 Whats On Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 MAGAZINE GROUP Editorial: Lauren Foster [email protected] -

A Free Monthly Guide to Music, Art, Theatre & Literature in Stroud

Issue #2 May 2015 A free monthly guide to Music, Art, Theatre & Literature in Stroud Photo: James Kriszyk EDITORS’ NOTE WELCOME TO THE SECOND ISSUE OF GOOD ON PAPER – YOUR NEW FREE MONTHLY GUIDE TO MUSIC CONCERTS, ART EXHIBITIONS, THEATRE PRODUCTIONS AND CONTENTS LITERATURE EVENTS IN STROUD... For this month’s issue we’ve had a little more time to 4 - 5 Music: Trading Post focus in on the design so you may notice some small changes and improvements. We have also amassed 6 - 9 Music: Listings a new horde of contributing writers including Jess 10 - 11 Arts: Select Festival Bracey, Helen Elliott-Boult, Siobain Drury and Jamie Baldwin, all providing you with in-depth information 12 - 13 Arts: Site Festival Open Studios on arts festivals, a time-honoured local record shop 14 - 15 Arts: Listings and a soon to be released anthology of short stories featuring the work of over fifty authors. 16 Theatre: Previews 17 Theatre: Listings They join our regular theatre columnist John Bassett from Spaniel in the Works Theatre Company and our 18 Literature: Stroud Short Stories resident photographer James Kriszyk. 19 Literature: Listings In other news we are happy to announce that Good 20 - 21 Exhibition Space: Kerry Phippen On Paper will be curating an event as part of this 22 Contacts and Stockists year’s Stroud Fringe Festival! Due to take place in the grand Centre for Science and Art building on Lansdown we will be putting together an evening of music, art, theatre and literature representing each section of the magazine. More info coming soon.. -

Mstr Pbr4.Indd

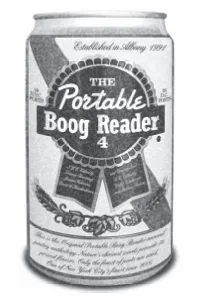

WWW.WELCOMETOBOOGCITY.COM BOOG CITY 1 Launch Party for VANITAS 4: The Portable Boog Reader 4 TRANSLATION IS OUT!! annual poetry anthology Translations, versions, adaptations, Sun., Jan. 17, 7:00 p.m. homophonics, riffs, $5 fragments, experiments by Charles Borkhuis, Zinc Bar Jen Hofer, Ron Padgett, Mónica de la Torre, Paul 82 W. 3rd St. Violi, Anne Waldman, (Sullivan/Thompson sts.) Bill Zavatsky, and NYC many more. Also poems by Alan Davies, WITH READINGS FROM Ray DiPalma, Joanna PBR4 CONTRIBS Fuhrman, Lisa Jarnot, Steven Karl, Elizabeth N.Y.C. poets: Young, and others. Critical texts by Charles Bernstein, Michael Lally, Yuko Otomo, Kit Robinson, Raphael Ivy Johnson * Boni Joi Rubinstein, Eileen R. Tabios, and Lewis Warsh. Art by Steven Karl * Ada Limon Francesco Clemente, with additional visual work by Augusto de Campos and Brandon Downing. D.C. poets: For copies, go to Small Press Distribution (www. spdbooks.org) or the Vanitas homepage (www. Lynne Dreyer * Phyllis Rosenzweig vanitasmagazine.net). Also on facebook. Directions: A/B/C/D/E/F/V to W. 4th St. Forthcoming from Libellum books, two by Tom Clark: For further information: The New World (new poems) and TRANS/VERSIONS 212-842-BOOG (2664), [email protected] (translations). 2 BOOG CITY WWW.WELCOMETOBOOGCITY.COM Publisher’s Letter N.Y.C. elcome to The Portable Boog Reader 4. The first Andrea Baker Wthree editions of our now annual anthology Macgregor Card of poetry have featured work only from New York City Lydia Cortes writers, the last two selected by six-person editorial Cynthia Cruz 4 collectives. This time around the four New York City editors— Pam Dick Sommer Browning, Joanna Fuhrman, Urayoán Noel, Mary Donnelly Will Edmiston and me—took our usual 72 poets and designated 48 to Laura Elrick be from New York City, with 24 to come from a sister 5 city. -

ENG 3062-001: Intermediate Poetry Writing Charlotte Pence Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Fall 2015 2015 Fall 8-15-2015 ENG 3062-001: Intermediate Poetry Writing Charlotte Pence Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/english_syllabi_fall2015 Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Pence, Charlotte, "ENG 3062-001: Intermediate Poetry Writing" (2015). Fall 2015. 67. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/english_syllabi_fall2015/67 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 2015 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fall 2015 by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENGLISH 3062: INTERMEDIATE POETRY WRITING FALL 2015 3 CREDIT HOURS Dr. Charlotte Pence Course Information: Email: [email protected] MW 3-4:15 Office: 3745 Coleman Hall Room: CH 3159 Office Hours: MW 12:30-3 Section 001 and by appointment. REQUIRED TEXTS AND MATERIALS o The Poet’s Companion: A Guide to the Pleasures of Writing Poetry edited by Kim Addonizio and Dorianne Laux o Poetry: A Pocket Anthology, 7th Edition, Edited by R.S. Gwynn. (Bring to every class.) o The Alchemy of My Mortal Form by Sandy Longhorn ($15) o Course Packet with additional readings from Charleston Copy X, 219 Lincoln Ave. o A writer’s notebook of your choice. (Bring to every class.) o Three-ring binder or folder to keep all of the poems and handouts. COURSE DESCRIPTION Poet Richard Wilbur once remarked that “whatever margins the page might offer have nothing to do with the form of a poem.” In this intermediate course centered on the writing of poetry, we will accept Wilbur’s challenge and learn the variety of ways we can give shape to our lyrical expressions. -

Langdon Review Weekend September 9 – 12, 2009

Langdon Review Weekend September 9 – 12, 2009 Dora Lee Langdon Center Granbury, Texas Tarleton State University Stephenville, Texas Co-Editors: Moumin Quazi and Marilyn Robitaille Editorial Advisory Board Phyllis Allen Judy Alter Betsy Berry Alice Cushman Robert L. Flynn Todd Frazier Don Graham Dominique Inge James Hoggard Lynn Hoggard James Ward Lee Natrelle Long Jill Patterson Tom Pilkington Punch Shaw Thea Temple Richard Tuerk Cheryl Vogel Donna Walker-Nixon Betty Wiesepape 2009-2010 Contributors Scott Grant Barker Gregg Barrios Yvette Benavides Jerry Bradley Cassy Burleson Kevin Clay Jerry Craven Sherry Craven Jeffrey DeLotto Tom Dodge Peggy Freeman David Lowery Naomi Shihab Nye Eugenio R. Garcia Orts Danny Parker Mike Price Jessica Quazi Paul Ruffin Barrie Scardino Judith Segura 2 General Information REGISTRATION: The registration desk in the Langdon House will open beginning Thursday morning at 8:30 a.m. and continuing throughout the Langdon Review Weekend. VENUE: All events with the exceptions of the Wednesday Opening Events, the film screening, and the Picnic with the Poet Laureate take place at the Dora Lee Langdon Center. The Studio, the Carriage House, the Rock House, and the Concert Hall are all within shouting distance of the Gordon House where registration is taking place. EXHIBITS: Various writers have been invited to display their books at a table in the Studio. Feel free to browse and ultimately purchase books. Say hello to Christina Stradley, Tarleton Campus Store manager extraordinaire. BREAK AREA: From 10:00 a.m. until 2:00 p.m., help yourself to the snacks provided. Look for the tents on the Langdon Center Lawn.