Moving Amid the Mountains, 1870-1930 COLE HARRIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraser River from Source to Mouth

FRASER RIVER FROM SOURCE TO MOUTH September 5, 2017 - 11 Days Fares Per Person: $3395 double/twin $4065 single $3210 triple > Please add 5% GST. Early Bookers: $160 discount on first 12 seats; $80 on next 8 > Experience Points: Earn 76 points from this tour. Redeem 76 points if you book by July 5. Includes Flight from Victoria to Kelowna St. John the Divine Church in Yale Coach transportation for 10 days Harrison Hot Springs pools 10 nights of accommodation & hotel taxes Copper Room music & dancing with Jones Boys Helicopter to the source of the Fraser River Fraser River Safari boat excursion Fraser River raft float trip (no white water) Paddlewheeler cruise from New Westminster Huble Homestead tour to the mouth of the Fraser River Farwell Canyon and pictographs Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site Cariboo Chilcotin Museum Transfer from New Westminster to Victoria Hat Creek Historic Ranch and roadhouse tour Knowledgeable tour director Hell’s Gate Airtram Luggage handling at hotels Alexandra Suspension Bridge 21 meals: 8 breakfasts, 9 lunches, 4 dinners Activity Level This is a unique tour with lots of activity and time outdoors while you experience many aspects of the Fraser River. The trip to the source of the Fraser requires getting in and out of a helicopter, and walking about ½ km in an alpine meadow at 2,000 metres altitude. On other days, you are boarding a large raft and two boats. Walks in- clude Farwell Canyon pictographs, Alexandra Bridge, and the boat dock to Kilby Store. This tour has activity ranging from somewhat rigorous to sedentary. -

KR/KL Burbot Conservation Strategy

January 2005 Citation: KVRI Burbot Committee. 2005. Kootenai River/Kootenay Lake Conservation Strategy. Prepared by the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho with assistance from S. P. Cramer and Associates. 77 pp. plus appendices. Conservation strategies delineate reasonable actions that are believed necessary to protect, rehabilitate, and maintain species and populations that have been recognized as imperiled, but not federally listed as threatened or endangered under the US Endangered Species Act. This Strategy resulted from cooperative efforts of U.S. and Canadian Federal, Provincial, and State agencies, Native American Tribes, First Nations, local Elected Officials, Congressional and Governor’s staff, and other important resource stakeholders, including members of the Kootenai Valley Resource Initiative. This Conservation Strategy does not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or approval of all individuals or agencies involved with its formulation. This Conservation Strategy is subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of conservation tasks. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho would like to thank the Kootenai Valley Resource Initiative (KVRI) and the KVRI Burbot Committee for their contributions to this Burbot Conservation Strategy. The Tribe also thanks the Boundary County Historical Society and the residents of Boundary County for providing local historical information provided in Appendix 2. The Tribe also thanks Ray Beamesderfer and Paul Anders of S.P. Cramer and Associates for their assistance in preparing this document. Funding was provided by the Bonneville Power Administration through the Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Fish and Wildlife Program, and by the Idaho Congressional Delegation through a congressional appropriation administered to the Kootenai Tribe by the Department of Interior. -

Okanagan Valley

OKANAGAN VALLEY DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY HIGHLIGHTS MYRA CANYON Photo: Grant Harder THANK WHAT’S YOU INSIDE The Okanagan Valley Destination Thank you to our tourism partners 1. INTRODUCTION Development Strategy is the outcome who participated in the process by of a nineteen-month, iterative process attending community meetings, 2. REALIZING THE POTENTIAL of gathering, synthesizing, and participating in surveys and validating information with tourism interviews, engaging in follow-up 3. AT A GLANCE partners about the current status conversations, and forwarding 4. GEARING UP and future direction of tourism in relevant documents and insights. the Okanagan Valley planning area. Special thanks to the members of the Working Group, as well as the We thank the Syilx people and the facilitator of the destination Okanagan Nation on whose traditional development process. territories we gathered for meetings in Kelowna and Summerland. OKANAGAN VALLEY | 2 1 INTRODUCTION WHY A STRATEGY? District, and part of electoral area E (West Boundary) the creation of a provincial destination development of the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary. strategy thereby ensuring a truly integrated and The Okanagan Valley Destination Development Municipalities include Lake Country, Kelowna, West cohesive combination of bottom-up and top-down Strategy was developed to enhance the competitiveness Kelowna, Peachland, Summerland, Penticton, Oliver, destination planning. of the Okanagan Valley planning area over the next 10 Keremeos, and Osoyoos. The planning area includes years and beyond. The strategy was developed as part most of the Okanagan Valley, Sakha Lake, and the of Destination BC’s Destination Development Program Okanagan River. A KEY IMPERATIVE to support and guide the long-term growth of tourism in British Columbia. -

Community Risk Assessment

COMMUNITY RISK ASSESSMENT Squamish-Lillooet Regional District Abstract This Community Risk Assessment is a component of the SLRD Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan. A Community Risk Assessment is the foundation for any local authority emergency management program. It informs risk reduction strategies, emergency response and recovery plans, and other elements of the SLRD emergency program. Evaluating risks is a requirement mandated by the Local Authority Emergency Management Regulation. Section 2(1) of this regulation requires local authorities to prepare emergency plans that reflects their assessment of the relative risk of occurrence, and the potential impact, of emergencies or disasters on people and property. SLRD Emergency Program [email protected] Version: 1.0 Published: January, 2021 SLRD Community Risk Assessment SLRD Emergency Management Program Executive Summary This Community Risk Assessment (CRA) is a component of the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District (SLRD) Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan and presents a survey and analysis of known hazards, risks and related community vulnerabilities in the SLRD. The purpose of a CRA is to: • Consider all known hazards that may trigger a risk event and impact communities of the SLRD; • Identify what would trigger a risk event to occur; and • Determine what the potential impact would be if the risk event did occur. The results of the CRA inform risk reduction strategies, emergency response and recovery plans, and other elements of the SLRD emergency program. Evaluating risks is a requirement mandated by the Local Authority Emergency Management Regulation. Section 2(1) of this regulation requires local authorities to prepare emergency plans that reflect their assessment of the relative risk of occurrence, and the potential impact, of emergencies or disasters on people and property. -

British Columbia 1858

Legislative Library of British Columbia Background Paper 2007: 02 / May 2007 British Columbia 1858 Nearly 150 years ago, the land that would become the province of British Columbia was transformed. The year – 1858 – saw the creation of a new colony and the sparking of a gold rush that dramatically increased the local population. Some of the future province’s most famous and notorious early citizens arrived during that year. As historian Jean Barman wrote: in 1858, “the status quo was irrevocably shattered.” Prepared by Emily Yearwood-Lee Reference Librarian Legislative Library of British Columbia LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA BACKGROUND PAPERS AND BRIEFS ABOUT THE PAPERS Staff of the Legislative Library prepare background papers and briefs on aspects of provincial history and public policy. All papers can be viewed on the library’s website at http://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/ SOURCES All sources cited in the papers are part of the library collection or available on the Internet. The Legislative Library’s collection includes an estimated 300,000 print items, including a large number of BC government documents dating from colonial times to the present. The library also downloads current online BC government documents to its catalogue. DISCLAIMER The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily represent the views of the Legislative Library or the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia. While great care is taken to ensure these papers are accurate and balanced, the Legislative Library is not responsible for errors or omissions. Papers are written using information publicly available at the time of production and the Library cannot take responsibility for the absolute accuracy of those sources. -

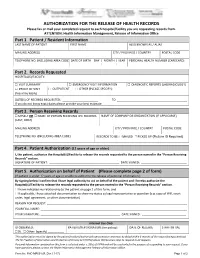

AUTHORIZATION for the RELEASE of HEALTH RECORDS Please Fax Or Mail Your Completed Request to Each Hospital/Facility You Are Requesting Records From

AUTHORIZATION FOR THE RELEASE OF HEALTH RECORDS Please fax or mail your completed request to each hospital/facility you are requesting records from. ATTENTION: Health Information Management, Release of Information Office Part 1. Patient / Resident Information LAST NAME OF PATIENT FIRST NAME ALSO KNOWN AS / ALIAS MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) DATE OF BIRTH DAY | MONTH | YEAR PERSONAL HEALTH NUMBER (CARECARD) | | Part 2. Records Requested HOSPITAL(S)/FACILITY: □ VISIT SUMMARY □ EMERGENCY VISIT INFORMATION □ DIAGNOSTIC REPORTS (LAB/RADIOLOGY) □ PROOF OF VISIT □ OUTPATIENT □ OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY): (fees may apply) DATE(S) OF RECORDS REQUESTED: ______________________ TO ___________________________________________ If you do not know exact dates please provide your best estimate Part 3. Person Receiving Records □ MYSELF OR □ NAME OF PERSON RECEIVING THE RECORDS NAME OF COMPANY OR ORGANIZATION (IF APPLICABLE) (LAST, FIRST) MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) RECORDS TO BE: □ MAILED □ PICKED UP (Picture ID Required) Part 4. Patient Authorization (12 years of age or older) I, the patient, authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. SIGNATURE OF PATIENT: ___________________________________________ DATE SIGNED: ____________________________ Part 5. Authorization on behalf of Patient (Please complete page 2 of form) (If patient is under 12 years of age or unable to authorize the release of personal information.) By signing below I confirm that I have legal authority to act on behalf of the patient and I hereby authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. -

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867”

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867” The format would include a 45 minute talk on the subject with Power Point illustrations, followed by a 15 minute question and answer period. Sunday, November 19, 1:30 pm - The First Nations – First of all, I will outline the geographical setting and then examine the culture of the Plateau Native People both pre-horse and post-horse, with particular attention to the Okanagans. The lecture will look at the subsistence culture of the Plateau First Nations, both the Salish and Sahaptan language groups and the changes that the coming of the horse brought about. I will look at their annual cycle, material culture and inter-tribal trade routes with a focus on the Okanagan Valley trail that connected the Columbia and Fraser River drainage systems. Saturday, November 25, 1:30 pm - The Fur Traders from 1811 to 1847– Beginning with the first contact with white traders such as David Thompson of the North West Company and David Stuart of the Pacific Fur Company, I will look at the routes followed and the trading posts established, particularly in the Okanagan Valley and its vicinity. The brigade trail, which ran through the Okanagan Valley from Fort Okanagan to Fort Kamloops and beyond, was the major transportation route in the Interior. I will also examine the relationship between the traders and the First Nations and the inevitable tensions of this “clash of cultures.” Sunday, December 3, 1:30 pm - The Miners’ Brigades and the Traders from 1858 to 1866 – Beginning in early 1858, there was a rush of miners to the Lower Fraser River, mostly though Victoria and Fort Langley. -

October 11Th, 2016, COTW THAT the COTW Adopts The

THE CORPORATION OF THE CITY OF GRAND FORKS AGENDA - COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE MEETING Tuesday, October 11, 2016, at 9:00 am 7217 - 4th Street, Council Chambers City Hall ITEM SUBJECT MATTER RECOMMENDATION 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE AGENDA a) Adopt agenda October 11th, 2016, COTW THAT the COTW adopts the agenda as presented. b) Reminder In-Camera Meeting directly following COTW Meeting 3. REGISTERED PETITIONS AND DELEGATIONS a) The Boundary Museum Society Quarterly report presentation THAT the COTW receives for Delegation - The Boundary Museum information the verbal Society quarterly report from The Boundary Museum Society and refers the Fee for Service request to the 2017 budgeting process. b) Boundary Country Regional Chamber Quarterly report presentation THAT the COTW receives for of Commerce information the verbal Delegation - Boundary Country Reg. quarterly report from the Chamber of Commerce Boundary Country Regional Chamber of Commerce and refers the Fee for Service request to the 2017 budgeting process. c) Grand Forks Art Gallery Society Quarterly report presentation THAT the COTW receives for Delegation - Grand Forks Art Gallery information the quarterly Society report from the Grand Forks Art Gallery Society and refers the letter of request to the October 24th, 2016, Regular Meeting Summary of Information Items for decision. 4. REGIONAL TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION - WITH AREA D a) Roly Russell, Area D Director Topics for discussion: THAT the COTW receives for Roly Russell, Area D Director - Boundary Area Agricultural information and discussion Boundary Area Agricultural Plan & Plan and Food Security the presentation from Area D Food Security Project Update Project Update Director, Roly Russell, regarding the Boundary Area Agricultural Plan and Food Security Project Update. -

Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1983 Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians Cynthia J. Manning The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Manning, Cynthia J., "Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians" (1983). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5855. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5855 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished m a n u s c r ip t in w h ic h c o p y r ig h t su b s i s t s . Any further r e p r in t in g of it s c o n ten ts must be a ppro ved BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD L ib r a r y Un iv e r s it y of Montana D a te : 1 9 8 3 AN ETHNOHISTORY OF THE KOOTENAI INDIANS By Cynthia J. Manning B.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1978 Presented in partial fu lfillm en t of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1983 Approved by: Chair, Board of Examiners Fan, Graduate Sch __________^ ^ c Z 3 ^ ^ 3 Date UMI Number: EP36656 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Link to Full Text

~ .......... ~ ~ - - -- .. ~~ -- .... ..... .., - .. - ... ...., .... IX. ADYNAMIC HESEHV01H SIMULATION MODEL-DYHESM:5 i\ 311 c. transverse and longitUdinal direction playa secondary role and only the variations) ." I in the vertical enter lhe first order balances of mass, momentum and energy. 1/ I Departures from this Stilte of horizontalisopyc'nalsare possible, but these \ tI l A DYNAMIC RESERVOIR SIl\olULATION MODEL enter only as isolated events or as \I/eak pe.!lurbatiQ.D.S. In both cases the.•net eJJ;cJ,J CI DYRESM: 5 is e~plured wi(h a parame!efizalion of their inp,ut (0 the vertical s(rUelure"iiild , ) I comparison of the model prediction and field data must thus be confined to ~ ~ .....of.............,.calm when the structure is truly one-dimensional. lorg 1mberger and John C.. Pattetsun .. ~ ,. The constraints imposed by ~uch a one-dimer.:Jional model may best be University of Western Australia quantified by defining a series of non-dimensional llUmbers. The value of the Nedlands, Western Australia Wedderburn number :) LV =.i.!!.. h (.J" I I '( 14.2 • L- '7 y(l .. n, (I) , \ ..,' I / 1. INTRODUCTION where g' is an effective reoufed gravity across the thermocline, h the depth of the mixed layer, L the basin scale, and u· the surface shear velocity, is a measure of """·".',j<}·,t-·;~·'",,,"~~,'ti The dynamic reservoir simulation model, DYRESM, is a one-dimensional the activity within the mixed layer. Spigel and Imberger (I980) have shown thah, numerical model for the prediction of temperature and salinity in small to medium for W > 00) the departure fmm one-dimensionality is minimal and for I ':I sized reservoirs and Jakes. -

Mining in British Columbia

BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF MINES HON. R. E. SOMMERS, Minister JOHN F. WALKEE, Deputy Minister MINING IN BRITISH COLUMBIA An Outline of the Development of the Industry VICTORIA, B.C. Printed by DON MCDIARMID, Printer to the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty 1954 BCEMPR MiSC PUB-33 c.3 nisc 0005073968 PUB-33 c-3 BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF MINES E. SOMMERS, Minister JOHN F. WALKER, Deputy Minister MINING IN BRITISH COLUMBIA An Outline of the Development of the Industry VICTORIA, B.C. Primed by DON MCDIAHMID, Printer to the Queen's Most Excellent Majesty 1954 This pamphlet deals principally with the history of mining activity in British Columbia to the end of the year 1953. The written account is supplemented by a selection of photographs. MINING IN BRITISH COLUMBIA It is a curious fact that, although what is now British Columbia possessed a vast wealth of visible resources, little attention was paid to them in the eighty years following Captain Cook's visit to the west coast of Vancouver Island in 1778. Such interest as was aroused was mainly in furs. It was interest in fur that led John Meares to establish his short-lived post at Nootka, and interest in fur that spurred Alexander Mackenzie, Simon Fraser, and David Thompson to undertake their arduous expeditions into British Colum• bia from the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains. In the period from 1805 to 1849 fifteen posts were established along the routes of the fur brigades, and here and there the Oblate Fathers had planted churches among the tribes. -

Certificate of Insurance

CERTIFICATE OF INSURANCE THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT POLICIES OF INSURANCE AS HEREIN DESCRIBED HAVE BEEN ISSUED TO THE INSURED NAMED BELOW AND ARE IN FORCE AT THE DATE HEREOF. THIS CERTIFICATE IS ISSUED AT THE REQUEST OF: NAME OF INSURED SEE ATTACHED BC AMATEUR BASEBALL ASSOCIATION, BC BASEBALL UMPIRE ASSOCIATION & AFFILIATED MEMBER CLUBS, LEAGUES, ASSOCIATIONS LOCATIONS AND OPERATIONS TO WHICH THIS CERTIFICATE APPLIES BRITISH COLUMBIA ABOVE ARE ADDED AS ADDITIONAL INSURED, BUT SOLELY WITH RESPECT TO THE LIABILITY WHICH ARISES OUT OF THE ACTIVITIES OF THE NAMED INSURED. “SANCTIONED BASEBALL ACTIVITIES” *CONTAGION EXCLUSION TO WHOM NOTICE WILL BE MAILED IF SUCH INSURANCE IS CANCELLED OR IS CHANGED IN SUCH A MANNER AS TO AFFECT THIS CERTIFICATE SEPTEMBER 9, 2020 TO APRIL 1, 2021 KIND OF POLICY POLICY NO. INSURERS LIMIT OF LIABILITY GENERAL LIABILITY AL2603 CERTAIN LLOYD’S UNDERWRITERS AS $5,000,000.00 LIMIT ARRANGED BY MARKEL CANADA LIMITED Per occurrence and in the aggregate with respect to products & completed operations DEDUCTIBLE $500.00 POLICY EXTENSIONS: CROSS LIABILITY CLAUSE INCLUDED PARTICIPANT COVERAGE INCLUDED SUBJECT TO 30 DAYS WRITTEN NOTICE OF CANCELLATION THE INSURANCE AFFORDED IS SUBJECT TO THE TERMS, CONDITIONS, AND EXCLUSIONS OF THE APPLICABLE POLICY. SBC INSURANCE AGENCIES LTD. ___________________________________ AUTHORIZED REPRESENTATIVE 250 – 999 Canada Place, Vancouver, BC, V6C 3C1 Tel (604)737-3018 Fax (604) 333-3401 September 9, 2020 VL SBC Insurance Agencies Ltd. #250 – 999 Canada Place Vancouver, BC V6C 3C1 Tel (604)