Quantum Meruit: Recent Developments G. John Digby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Newsletter [2018] No 9, 8 November 2018](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7377/newsletter-2018-no-9-8-november-2018-737377.webp)

Newsletter [2018] No 9, 8 November 2018

NEWSLETTER [2018] No. 09 2018 ANNUAL ESSAY PRIZE Dr Nuncio d’Angelo Professor Gino Dal Pont The winner of the Academy’s Annual essay Prize Mr Russell Miller AM for 2018 is Ms Ashleigh Mills, who is a solicitor Dame Sian Elias GNZM PC QC and members of the employed at Holding Redlich in Sydney. Academy at the AGM The prize (of $10,000) will be presented to Ms Mills at the Academy’s book launch event to be held on 28 November (see under “Forthcoming Events” below). The Academy is much indebted to the Judging Panel comprising Professor the Hon William Gummow AC QC (Chair), Ms Kate Eastman SC and Professor James Stellios for their work in judging the essays. As was noted at the Annual General Meeting, Professor Croucher did not stand again for the ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING office of Director due to her having assumed the The annual general meeting of the Academy was role of Chair of the Asia Pacific Forum of held at the Federal Court in Melbourne National Human Rights Institutions (in addition immediately prior to the Patron’s Address at the to her responsibilities as President of the same location (see under “RECENT EVENTS” Australian Human Rights Commission). The below). President noted with thanks the indebtedness of the Academy to Professor Croucher for the The following were elected as directors and to major contribution that she has made as a the particular offices where shown Director. The meeting welcomed as a new Director Professor Gino Dal Pont of the President University of Tasmania Law School. -

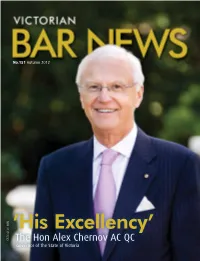

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

![Newsletter [2021] No](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7261/newsletter-2021-no-2077261.webp)

Newsletter [2021] No

NEWSLETTER [2021] No. 5 l 2 8 May 2021 Welcome to the fifth Newsletter for 2021. committee. The committee has met to plan how we may First Nations Scholarship implement this scheme. The details of this inaugural award are on the website. The idea is to establish a system whereby (generally) The second phase of the project was to find a Fellow junior academics may spend a day or two with a judge as mentor for the winner and Fellows as mentors for to gain, or renew, firsthand experience of how a court the other shortlisted applicants. This has been runs. Chief Justices and other heads of jurisdiction achieved. There is also a mentor for each of the other will need to be consulted. applicants. I am most grateful to those who have A proposal for a pilot scheme will go before the volunteered. It should be a rewarding experience, on Board shortly. both sides. 2021 AAL Essay Prize Forthcoming Events Please bring this competition to the attention of Dinner in Hobart, Tasmania, Thursday 10 June anyone who may be interested in submitting an essay. 2021 at 7 PM Fellows (other than Directors) may wish to If you will be in Hobart on 10 June 2021 and wish to participate themselves. attend, please notify the Secretariat as soon as Each year since the Essay Prize was established in possible: [email protected] 2015, the winning essay has been published in the Partners are invited. Australian Law Journal. The format will be an after-dinner speech by the new The essay topic for this year is: Dean of the Faculty of Law of the University of “Outstanding fundamental issues for First Nations Peoples in Tasmania, Professor Michael Australia: what can lawyers contribute to the current debates Stuckey. -

Faculty of Law Research Report 2006 Contents

Faculty of Law Research Report 2006 CONTENTS Message from the Associate Dean (Research) 1 Australian Research Council (ARC) Fellowships 2 ARC Federation Fellowship – Tim Lindsey 4 ARC Research Fellowship – Christine Parker 6 ARC Postdoctural Fellowship – Ann Genovese 8 Funded Research 10 Grants Commencing in 2006 11 Selected Grants in Progress 14 Centres and Institutes 27 Asian Pacific Centre for Military Law 28 Asian Law Centre 30 Centre for Employment and Labour Relations Law 33 Centre for Corporate Law and Securities Regulation 36 Centre for Media and Communications Law 38 Centre for Resources, Energy and Environmental Law 40 Centre for Comparative Constitutional Studies 42 Centre for the Study of Contemporary Islam 45 Intellectual Property Research Institute of Australia 48 Institute for International Law and Humanities 50 The Tax Group 53 Academic Research Profiles 55 Simon Evans 56 Belinda Fehlberg 58 Michelle Foster 60 Andrew Mitchell 62 Published Research 64 Journals And Newsletters 75 Journal Affiliations 79 Faculty Research Workshop Series 86 International Research Visitors Scheme 90 Student Published Research Prize 91 Academic Staff 92 Research Higher Degrees Completed in 2006 101 Research Degrees in Progress 103 message from the associate DeaN (research) It is a great pleasure to present this report on the research activities in the Faculty of Law during 2006. The Faculty was delighted to have three Australian Research Council (ARC) Fellowships commence in 2006. Professor Tim Lindsey began his Federation Fellowship on Islam and Modernity: Syari’ah, Terrorism and Governance in South East Asia, Associate Professor Christine Parker began her ARC Research Fellowship on The Impact of ACCC Enforcement Action: Evaluating the explanatory and normative power of responsive regulation and responsive law and Dr Ann Genovese began her ARC Postdoctoral Fellowship on Has Feminism Failed the Family? A History of Equality, Law and Reform. -

2012-13 Annual Report

Supreme Court of Victoria 2012–13 ANNUAL REPORT Letter to the Governor October 2013 To His Excellency Alex Chernov AO QC, Governor of the State of Victoria and its Dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia. Dear Governor, We, the judges of the Supreme Court of Victoria, have the honour of presenting our Annual Report pursuant to the Supreme Court Act 1986 with respect to the financial year of 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2013. Yours sincerely, Marilyn L Warren AC The Honourable Chief Justice Supreme Court of Victoria C Maxwell, P J H L Forrest, J P Buchanan, JA L Lasry, J G A A Nettle, JA J G Judd, J M A Neave, AO JA P N Vickery, J R F Redlich, JA E J Kyrou, J M Weinberg, JA D F R Beach, J P M Tate, JA J Davies, J R S Osborn, JA T M Forrest, J S P Whelan, JA K L Emerton, J P G Priest, JA C E Croft, J P A Coghlan, JA A Ferguson, J K M Williams, J M L Sifris, J S W Kaye, J P W Almond, J E J Hollingworth, J J R Dixon, J K H Bell, J C C Macaulay, J K W S Hargrave, J K McMillan, J B J King, J G H Garde, AO RFD J A L Cavanough, J G J Digby, J E H Curtain, J J D Elliott, J R M Robson, J T J Ginnane, J On the cover Elements of entries to the 2012 Chief Justice Prize for excellence in design feature on the cover. -

Report Publication of an Article Appearing In

No. 156 PARLIAMENT OF NEW SOUfH WALES LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL STANDING CO:MlVlITTEE UPON PARLIAMENTARY PRIVll-EGE REPORT CONCERNING THE PUBLICATION OF AN ARTICLE APPEARING IN THE SUN HERALD NEWSPAPER CONTAINING DETAILS OF IN CAMERA EVIDENCE Ordered to be printed 28 October 1993 October 1993 i MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE The Honourable Beryl Alice Evans, B.Ec., M.L.C. (Chairman) The Honourable Richard Thomas Marshall Bull, M.L.C. The Honourable Ronald David Dyer, Dip.Law., Dip. Crim., M.L.C. The Honourable John Hughes Jobling, Ph.C., M.P.S., M.L.C. The Honourable Richard Stanley Leigh Jones, M.L.C. The Honourable James Miltiades Samios, M.B.E., B.A., LL.B., M.L.C. The Honourable Bryan Henry Vaughan, LL.B., M.L.C. Secretariat Ms Lynn Lovelock - Clerk to the Committee and Deputy Clerk of the Legislative Council Ms Giselle Dawson - Clerk Assistant-Procedure Ms Velia Mignacca - Project Officer Mrs Juliette Gollop - Secretary, Office of the Clerk of the Parliaments ii CHAIRMAN'S FOREWORD This inquiry arose from the unauthorised publication in the Sun Herald newspaper on 3 January 1993 of details of evidence given in camera before the Joint Select Committee Upon Police Administration. The purpose of the inquiry was, fIrstly, to attempt to ascertain the identity of the person who disclosed the information to the journalist who wrote the article. Secondly, the Committee had to determine whether the disclosure and publication of the information amounted to a breach of privilege or a contempt of Parliament. The Committee took evidence from the Chairman of the Joint Select Committee Upon Police Administration, from the author of the article, and from the acting editor of the Sun Herald who approved its publication. -

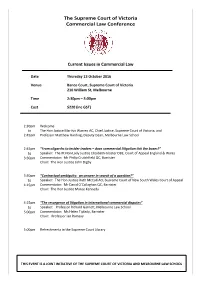

The Supreme Court of Victoria and Melbourne Law School

Current Issues in Commercial Law Date Monday, 9 September 2013 Venue Banco Court, Supreme Court of Victoria 210 Williams St, Melbourne Time 2.30pm – 5.00pm Cost $220 (incl GST) 2:30pm-2:45pm Welcome The Hon Justice Marilyn Warren, Chief Justice, Supreme Court of Victoria, and Professor Carolyn Evans, Dean, Melbourne Law School 2:45pm-3.30pm “Fiduciary Breaches: The Endless Wrangling over Remedies” Speaker: Professor Sarah Worthington, University of Cambridge Comment: The Hon Justice Marcia Neave AO Chair: The Hon Justice John Digby 3.30pm-4.15pm “Commercial Litigation and the Adversarial System – Time to Move On” Speaker: The Hon John Doyle AC QC Comment: The Hon Ray Finklestein QC Chair: The Hon Justice Simon Whelan 4:15pm-5.00pm “The Evidence Act and Developments in Legal Professional Privilege” Speaker: Dr Sue McNicol SC Comment: The Hon Justice Tim Ginnane Chair: The Hon Tim Smith QC 5:00pm Refreshments in the Supreme Court Library THIS EVENT IS A JOINT INITIATIVE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF VICTORIA AND MELBOURNE LAW SCHOOL Professor Sarah Worthington QC (hon) FBA is the Downing Professor of the Laws of England at the University of Cambridge, a Fellow of Trinity College and academic member of the 3-4 South Square, Gray’s Inn. She was made a Fellow of the British Academy in 2009. Her main research interests are in commercial equity and company law, especially secured financing and governance issues. She is a Bencher of Middle Temple and a Panel Member of PRIME Finance. She has worked with law reform bodies in the United Kingdom, Europe and Australia, including serving as a member of the Advisory Council for the Study Group for a European Civil Code, consultant to the UK Law Commission, and member of working groups of the Bank of England Financial Markets Law Committee and the UK Company Law Review. -

3512 Supplement to the London Gazette, 12 June, 1958

3512 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 12 JUNE, 1958 Walter Alexander EDMENSON, Esq., C.B.E.. STATE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA. D.L. For public services in Northern The Honourable Collier Robert CUDMORE, a Ireland. Member of the Legislative Council, State of Alderman John Wesley EMBERTON, J.P., D.L. South Australia, since 1933. For political and public services-in Cheshire. David Lewis EVANS, Esq., O.B.E., Deputy STATE OF VICTORIA. Keeper of the Records, Public Record Office. Professor Keith Grahame FEILING, O.B.E., The Honourable William John Farquhar Historian and Author. MCDONALD, Speaker of the Legislative . Assembly, State of Victoria. William Herbert GARRETT, Esq., M.B.E. For services to industrial relations. The Honourable Norman O'BRYAN, a Judge Alderman Richard Stephenson HARPER, J.P. of the Supreme Court, State of Victoria. For political and public services in Man- Norman DE WINTON ROBINSON, Esq., Chair- chester. man of the Amateur Turf Club in the State James 'William Francis HILL, Esq., C.B.E. For of Victoria. services to the Association of Municipal Corporations. COMMONWEALTH RELATIONS. Friston Charles How, Esq., C.B., Secretary, Walter Harold Strachan MICHELMORE, Esq., Atomic Energy Office. M.B.E., a member of the United Kingdom Willis JACKSON, Esq., Director of Research business community in India. and Education, Metropolitan Vickers Elec- The Honourable John Murray MURRAY, Chief itrical Company, Ltd. Justice of Southern Rhodesia. Kenneth Ivor JULIAN, Esq., C.B.E., Chairman, South East Metropolitan Regional Hospital Board. OVERSEAS TERRITORIES. Alderman Ronald Barry KEEFE. For political Roger Sewell BACON, Esq., M.B.E. Lately and public services in Norfolk. -

The Australian Jockey Club and the Victoria Racing Club

*Th e Australian Jockey Club and the Victoria Racing Club - Joint Proprietors of the Australian Stud Book since 1910 AUSTRALIAN STUD BOOK HISTORY Th e Australian Stud Book has a pedigree as long as some of the horses contained in it. For the fi rst seventy years it was mostly ‘kept’ by one family and over the last fi fty fi ve years it has only had four ‘keepers’. It ranks second to the American Stud Book with its 30,000 broodmares, 18,000 foals and nearly 20,000 breeders but could rank fi rst for services to breeders. Th e early history of the Australian Stud Book is the history of the men who established and nurtured it, and they lived interesting lives. From the early principle of “express purpose of preserving an offi cial record of the breeding industry in Australia and of assisting to improve the standard of the blood horse in the country” to “ensuring the integrity of thoroughbred breeding in Australia”, there has been much change to the way the Australian Stud Book operates. 2 3 EARLY COLONIAL STUD BOOKS is the second highest of any sport in Australia apart from Australian Football. Th ree of the colonies, Tasmania, New South Wales and From the earliest time, breeding was a most important factor in the Victoria, commenced stud books which could not be sustained. development of a satisfactory standard of racing in Australia. Initially, details of matings and bloodlines were recorded in a haphazard way. Tasmanian Stud Book Although the fi rst race meeting in Australia is generally regarded as Despite a Mr Chisholm’s early call in 1812 in the Sydney Gazette to being held in October 1810 at Hyde Park, Sydney, twenty two years those “desirous of improving their breed of horses”, the fi rst published after the fi rst settlement, it was not until 1842 that any attempt was stud book in Australia was the Tasmanian Stud Book, compiled in made to establish a Stud Book. -

The Supreme Court of Victoria Commercial Law Conference

The Supreme Court of Victoria Commercial Law Conference Current Issues in Commercial Law Date Monday 7 September 2015 Venue Banco Court, Supreme Court of Victoria 210 William St, Melbourne Time 2:30pm – 5:00pm Cost $220 (incl GST) 2:30pm – 2:45pm Welcome The Hon Justice Marilyn Warren AC, Chief Justice, Supreme Court of Victoria, and Professor Carolyn Evans, Dean, Melbourne Law School 2:45pm – 3:30pm “Understanding Causation and Attribution of Responsibility” Speaker: Justice James Edelman, Federal Court of Australia Commentator: Paul Anastassiou QC Chair: The Hon Justice John Digby 3:30pm – 4:15pm “Securities class actions- where to for market-based causation?” Speaker: Wendy Harris QC, Barrister Commentator: Belinda Thompson, Partner, Allens Chair: Professor Ian Ramsay 4:15pm – 5:00pm “Korda & ors v Australian Executor Trustees (SA) Limited [2015] HCA 6 “ Speaker: Dr Pamela Hanrahan, Associate Professor, Melbourne Law School Commentator: The Hon Justice Ross Robson Chair: The Hon Justice Melanie Sloss 5:00pm Refreshments in the Supreme Court Library THIS EVENT IS A JOINT INITIATIVE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF VICTORIA AND MELBOURNE LAW SCHOOL Session 1 The Hon Justice James Edelman was appointed to the Federal Court of Australia on 11 December 2014 having served as a judge of the Supreme Court of Western Australia since 2011. Justice Edelman commenced his Federal Court appointment on 20 April 2015 based in Brisbane. His Honour graduated from the University of Western Australia with a Bachelor of Economics (1995) and a Bachelor of Laws (1996), and from Murdoch University with a Bachelor of Commerce (1997). In 1997 his Honour was Associate to the Hon Justice Toohey of the High Court of Australia, and completed his articles with Blake Dawson Waldron and admitted to practice in Western Australia in 1998. -

Federal Elections 1993

Department of the Parhamentary J Library Federal Elections 1993 • J.1~ 'oj,' :' ~ :: :+ /"" -.dh- :.=... ~.. ~.:: ~.J.r~ .... J~ -'~__ ~.. ~.~_L~~~~~~:L~~ o ~ r ISSN 1037-2938 ~., Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 1993 Except to the extent ofthe uses pennitted under the Cop)'rigbt Act 1968, no part ofthis publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including infonnation storage and retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the Department of the ParliamentaJy Library, other than by Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. Published by the Department of the Parliamentery Library, 1993 / ) "I " Gerard Newman Andrew Kopras Statistics Group 8 October 1993 Parliamentary Research Service Background Paper Number 22 1993 Federal Elections 1993 Telephone: 06 2772480 Facsimile: 06 2772454 c '. c " This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Members ofthe Australian Parliament. Readers outside the Parliament are reminded that this is not an Australian Government document, but a paper prepared by the author and published by the Parliamentary Research Service to contribute to consideration ofthe issues by Senators and Members. The views expressed in this Paper are those oftha author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Parliamentary Research Service and are not to be attributed to the Department of the Parliamentary Library. CONTENTS Introduction 1 House ofRepresentatives ", Table 1 National Summary 3 c' 2 State Summary 4 3 Regional Summary 7 4 Party Status -

2016 Conference Program

The Supreme Court of Victoria Commercial Law Conference Current Issues in Commercial Law Date Thursday 13 October 2016 Venue Banco Court, Supreme Court of Victoria 210 William St, Melbourne Time 2:30pm – 5:00pm Cost $220 (inc GST) 2:30pm Welcome to The Hon Justice Marilyn Warren AC, Chief Justice, Supreme Court of Victoria, and 2:45pm Professor Matthew Harding, Deputy Dean, Melbourne Law School 2:45pm “From oligarchs to insider traders – does commercial litigation tick the boxes?” to Speaker: The Rt Hon Lady Justice Elizabeth Gloster DBE, Court of Appeal England & Wales 3:30pm Commentator: Mr Philip Crutchfield QC, Barrister Chair: The Hon Justice John Digby 3:30pm “Contractual ambiguity: an answer in search of a question?” to Speaker: The Hon Justice Ruth McColl AO, Supreme Court of New South Wales Court of Appeal 4:15pm Commentator: Mr David O’Callaghan QC, Barrister Chair: The Hon Justice Maree Kennedy 4:15pm “The resurgence of litigation in international commercial disputes” to Speaker: Professor Richard Garnett, Melbourne Law School 5:00pm Commentator: Ms Helen Tiplady, Barrister Chair: Professor Ian Ramsay 5:00pm Refreshments in the Supreme Court Library THIS EVENT IS A JOINT INITIATIVE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF VICTORIA AND MELBOURNE LAW SCHOOL Session 1 The Right Hon Dame Elizabeth Gloster DBE PC, was appointed a Lady Justice of Appeal, and consequently appointed to the Privy Council, on 9 April 2013. Dame Elizabeth was called to the Bar by the Inner Temple in 1971; in 1989 she was appointed a Queen's Counsel and made a Bencher of the Inner Temple in 1992.